A few years back I ran into Camille Brewer, a black American curator of contemporary art, on Frederick Douglass Boulevard in Harlem. “Look at this,” she said. She was turning the pages of Artforum, finding black artist after black artist. “It’s like Jet up in here.” Camille was referring to the glossy black news and entertainment magazine that had its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s. “Until you get to the [museum] appointments pages,” she added. “Then things go quiet again.” The black presence in the contemporary art scene continues to feel like a recent cultural phenomenon, though the group and individual exhibitions of black artists that prepared the way for this moment took place some time ago.

A landmark exhibition, “Contemporary Black Art in America,” at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1971, concerned primarily the abstract. It asserted a freedom achieved since the 1950s and 1960s when black artists such as Hale Woodruff, Norman Lewis, Beauford Delaney, and Romare Bearden were criticized for moving away from representation in their work, as if abstraction were a kind of opportunistic calculation. In 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (2016), his study of modernism as a cross-cultural exchange for black artists, Darby English identifies the paradox: if they escape from what he calls the “representationalist, collectivist black-ideological norm,” they end up being thought of as not having much to say on “racialist issues.”

It was therefore important for some to be able to find Africanist traces in abstract work by black artists. “Painting itself cannot practice discrimination,” English wrote. However, by 1970, when Jacob Lawrence’s portrait of Jesse Jackson appeared on the cover of Time, the debate about the representational versus the abstract was becoming a sideline. That same year, a black curator, Kynaston McShine, mounted “Information,” one of the first major exhibitions of conceptual art, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

“The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994,” Okwui Enwezor’s exhibition of 2001–2002, seen in Berlin and New York, among other places, put on display art that was a synthesis of African artistic styles and European modernism, almost as a peace treaty between cultures. By this time Glenn Ligon, the black conceptual artist, and Thelma Golden, the director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, had proclaimed the independence of what they called a “post-black” generation. To define “post-black” was one of the aims of Golden’s 2001 exhibition, “Freestyle.” Ligon and Golden spoke in the catalog of “the liberating value in tossing off the immense burden of race-wide representation, the idea that everything they do must speak to or for or about the entire race.” Black artists of the previous generation could say they did not want to be identified as black artists, but there was no need to go into further repudiations of the category when the only rule for black artists was that there weren’t any rules more important than to thine own self be true.

The catalog Four Generations: The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection of Abstract Art (2016), edited by Courtney J. Martin, shows that a history of blacks in American art can be told through means other than the representational or narrative. But the collection of Pamela Joyner and Alfred J. Giufridda also includes portrait photography and portrait painting. Time places the representational and the abstract in ever-closer cultural proximity. And the figurative has renewed importance now that painting enjoys a prestige that it has not had during the long ascendancy of conceptualism.

Hugh Honour tells us in The Image of the Black in Western Art (Vol. 4, 1989) that even though the number of artworks in which blacks were depicted increased in the 150 years from the abolitionism of the slave trade in Britain to the coming of modernism, such works were still a small fraction of those produced because there was no demand for them.* Moreover, there was a profound difference between representations of black people in the visual arts and in literature. They appeared in religious and genre painting, but apart from Goya, few artists in this period were stirred to record the truth of what black people experienced in white societies.

Because blacks were identified with slavery they could be victims but not heroes in Western art, though the exceptions are notable: Henry Fuseli’s The Negro Revenged (1806), Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819), or Joshua Reynolds’s Study of a Black Man (circa 1770). But public opinion limited where art sympathetic to blacks could be seen. And the violence of racial segregation in the US and of colonial expansion in Africa called for caricatures of darky inferiority and the ethnography of half-naked savages. Black people were ugly and so was their story. Racism casts a long shadow over art. Today’s portraits of black people come from a complex history about the subjectivity of beauty and the presence of blackness in Western art.

Advertisement

The portrait painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye was born in London in 1977. For her solo exhibition at the New Museum, “Under-Song for a Cipher,” the three high walls on which her work hung were painted leather-red. Art looks good held up by a color field. In Yiadom-Boakye’s seventeen unframed portraits of black people, the paint continues to the edges of each canvas. There are no titles or wall texts beside them. Some are full-length, or nearly so, except for a triptych of horizontal portraits of a black male in profile, not always in the same shirt, reclining on a red striped blanket. Three paintings are of women, one of whom wears a white leotard; another is seated Indian fashion, seeing to the bun in her hair. Two barefoot women in profile in long skirts are depicted together, one seated in front of the other, who stands with a pair of field glasses aimed at something we can’t see to our right. It is the only painting in the exhibition that is not of one person or of one person and a cat or a bird.

A young man in a blue sweater sits at a table with a coffee cup; another youth is on a chair, his left leg raised. One guy has a bird; a laughing black youth has a beard. A barefoot brown youth is standing with his right leg crossed in front of his left. He looks straight at the viewer. A black man with beautiful eyes looks at the cat on his shoulder. The largest painting shows a barefoot brown-purplish youth resting on his left elbow in a grassy expanse. The black youths are dark-skinned—dark brown, not black—and Yiadom-Boakye concentrates her impasto in the faces. Dark colors come up in ridges to form hair, nose, shadows, lips, neck, chin; and instead of white pigment unpainted spaces appear in a figure’s outline or as highlights on the face. The surface surrounding the figures is very flat, as if scraped. Backgrounds are a mist or zones holding the figure in place and are not meant to tell us much. The body is a road to the face, the central concern.

The guys are good-looking. A youth in profile in a white T-shirt is somewhat androgynous; a beautiful youth with downcast eyes is a harlequin. A sleeping youth appears Expressionist in his angles. He’s got no crotch, but here and there a guy’s trousers may sport a V. A young man in a black tank top holds an owl in his gloved hand. He has a thin mustache and his look down his nose at us is full of condescension. The owl, wonderfully painted, has its own fierce expression. In the catalog the painting has a title, The Matters. You get the feeling that these guys are meant to be dancers and—maybe it’s in what Yiadom-Boakye makes of the openness of their expressions—that they are gay.

It takes two to make a portrait as well as an argument, Hugh Honour wrote. Yet these are not portraits of real people. Yiadom-Boakye has explained that they are composites, from “a combination of different sources: scrapbooks, drawings, photographs.” She said she thinks less about the figures than she does about how they are painted. She does not see them as portraits of characters with personalities to capture or suggest. “They exist entirely in paint,” as a technical problem to be solved: how to render in oil the fleetingness of the snapshot. Far from photorealism, they nevertheless have something of a stranger’s photograph collection. They are private, a riddle.

Yiadom-Boakye has also discussed how she executes each portrait in a single day. If she feels a particular piece hasn’t worked out, she destroys it. She says she always remembers the failures. The art she cares about is political because most art is, she says, which may mean that as a black artist she can treat the black body as normal. Her portraits have attitude, but they are not heroic, just as she has said that she is suspicious of beauty and instead goes after the sensual, what the skin gives off. Her approach to portrait painting—the choice to impose a challenge, a framing device, some sort of distancing mechanism—also speaks of her generation, when painting in particular was unfashionable, and conceptual art, installations, were on the way to becoming the new academic art.

There is a purple-backed portrait by Yiadom-Boakye of a dark young woman’s head and neck in the Studio Museum in Harlem’s summer show, “Regarding the Figure.” More than fifty pieces taken from the museum’s permanent collection (including paintings, photographs, sculpture, and one work of mixed media) aren’t displayed chronologically, but they have the range to make the show about different ways of putting new images of the black (by black artists, following the Studio Museum’s mandate) into Western art. Henry Ossawa Tanner’s undated lithograph The Three Marys shares a wall with The Room (1949) by Eldzier Cortor, a small portrait, perhaps of Billie Holiday, and with Jennifer Packer’s Ivan, a sexy 2013 portrait.

Advertisement

As a young artist in Paris, Hale Woodruff met Tanner in the late 1920s. Tanner was the first African-American artist to win recognition abroad. The French government purchased his Resurrection of Lazarus for the Luxembourg in 1897. But it was Picasso who inspired Woodruff the most. He studied with Diego Rivera in Mexico in the 1930s and is best known for his murals at black colleges, yet his struggle with Picasso is still going on in his oil painting Africa and the Bull (circa 1958) in the Studio Museum show. Also in the show is Bob Thompson’s The Gambol, a forest scene of figures on horseback, or dancing alone, and dark for someone remembered as a colorist. One couple, mere shapes, appears to be copulating astride a horse. Thompson said he wanted Old Masters to meet a jazz-inflected Abstract Expressionism in his work. He died at twenty-eight, in 1966, before anyone could criticize him for Eurocentrism.

Among the historical forces that artists of the post-black generation have declared themselves unafraid of is the European aesthetic tradition, just as there is no more talk of who isn’t black enough in his or her work. Some of the artists in the Studio Museum exhibition can be seen in the major museums of the city, but it makes a difference to see them as part of a history that goes from work made in a society where so many took it for granted that a black artist would never be as good as—fill in a great white name—to objects that are just not worried about that kind of thing anymore. The Harlem exhibition goes from one arresting piece to another. There is Lawdy Mama (1969), Barkley L. Hendricks’s life-size portrait of his cousin, beige Kathy Williams, with a big, round, brown afro, posed against a background arch of gold leaf. (This calls out to an intense Pre-Raphaelite-like portrait with much gold leaf, Elizabeth Colomba’s Daphne (2015), on display in the “Uptown” exhibition at the new Columbia University School of the Arts Lenfest Center.)

In the Studio Museum show, Njideka Akunyili Crosby depicts a couple in a room, Nwantinti (2012), a large work of acrylic, pastel, charcoal, and colored pencil on unframed paper. The newsprint plastered on the walls of the meticulously neat room is a Xerox transfer of graduation and family photographs. Repeated often in the transfers is the cover of the record “Love Nwantinti,” by the Igbo singer Nelly Uchendu. (“My journey with love/It will begin in a short time.”) The transfers bleed into the man’s trousers, arm, torso, chin, the bedspread, the floor. The pink walls are bathed in light. It’s impossible to tell whether the few clothes in the open closet behind the bed are a man’s or a woman’s, though the lovely young brown woman with short hair is barefoot and those must be her flip-flops beside the bed. She sits toward the edge of the tidy bed, a tender expression on her face as she looks down at the young man on his back, his head in her tight lap. A light source from a door and window grill strikes his quiet face and it can’t be said for sure if he is white or mixed-race.

A sharp black-and-white photograph by Zanele Muholi, Bona, Charlottesville (2015), has a nude dark black woman on her back on a bed, shoulders to the viewer, the back of her head and knees up. She holds on her stomach a large round mirror, reflecting only her face. Lyle Ashton Harris’s double self-portrait (2000), Untitled (Face #155 Lyle) and Untitled (Back #155 Lyle), shows him and his braids close-up, in black-and-white. Part of his Chocolate Portraits series, the photographs’ size (twenty by twenty-four inches) only seems to increase the vulnerability of the subject. Lorna Simpson’s 9 Props (1995) is exquisite. Its nine black-and-white waterless lithographs on felt panels show gleaming black glass vases or bowls that Simpson commissioned. They are stand-ins for the figures in Van Der Zee photographs: the artist Benny Andrews, for instance, taken in 1976. The captions under the glassware describe the figures and the interiors of the original photographs. “Wearing a trench coat, he is seated with the right leg crossed and holds it with his right hand. To his left is a small table with a circular top and a vase with Chrysanthemums…”

An acrylic-painted plaster wall relief of a woman laughing, Maria (1981), is from a series of South Bronx portraits by John Ahearn. Freestanding in the gallery is a six-foot sculpture of a dapper black man of a certain age, made from urethane foam, plaster, hair, and clothes: Isaac Julien’s Incognito (2003), a portrait of Melvin Van Peebles with his signature cigar in the corner of his mouth. No, he’s not real, a white mother explained to her child as she pulled his hand back. The piece is a surprise, because Julien is known chiefly for his films, video works, and photography.

Nearby is a small bust, St. Francis of Adelaide (2006), by Kehinde Wiley’s studio. The sculpture is under glass, because—made from cast marble dust and resin, and the color of a once-lit candle—it invites caress. The figure of the saint is a muscular, shaven-headed black youth in a basketball jersey or wife beater, with his right arm cut off. He is posed in quarter profile, with his left hand hugging an orb, book, and scepter to his body. (It was made around the same time that Wiley produced two other busts—not in this exhibition—in editions of 250: one after Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s La Negresse, but instead of a thick-haired black woman with her left breast exposed, Wiley uses a male figure, the same model as for his Saint Francis. The second piece is after Bernini’s bust of Louis XIV, but Wiley’s Sun King is a goateed black youth in a hoodie, not armor.)

Wiley’s work in portraiture is mostly on a monumental scale. Born in Los Angeles in 1977, his oil paintings seize on the European tradition, replacing the august or prominent personage in a famous portrait with a young black person. Wiley has also portrayed young black people in the place of the figure of a saint in stained glass or oil paintings. He chooses a highly processed realism for his black subjects, male and female, usually hip-hop in their fashion sense but sometimes haute couture, and very post-black in their hairstyles. The subject alone makes a cultural contrast with Wiley’s usual backgrounds of elaborate decorative motifs.

He bestows a different kind of visibility on black urban youth, and in his free use of the history of Western art it is hip to say that he demystifies it, makes up for that tradition of aristocratic portraiture in which blacks are depicted as adoring servants, almost pets. But actually he ends up doing something else, which is to make the viewer interested in his sources. For the most part black artists have aligned themselves with artistic movements that sought liberation from the past. Wiley is different; the past is not only an influence, it’s also a presence, a stage character.

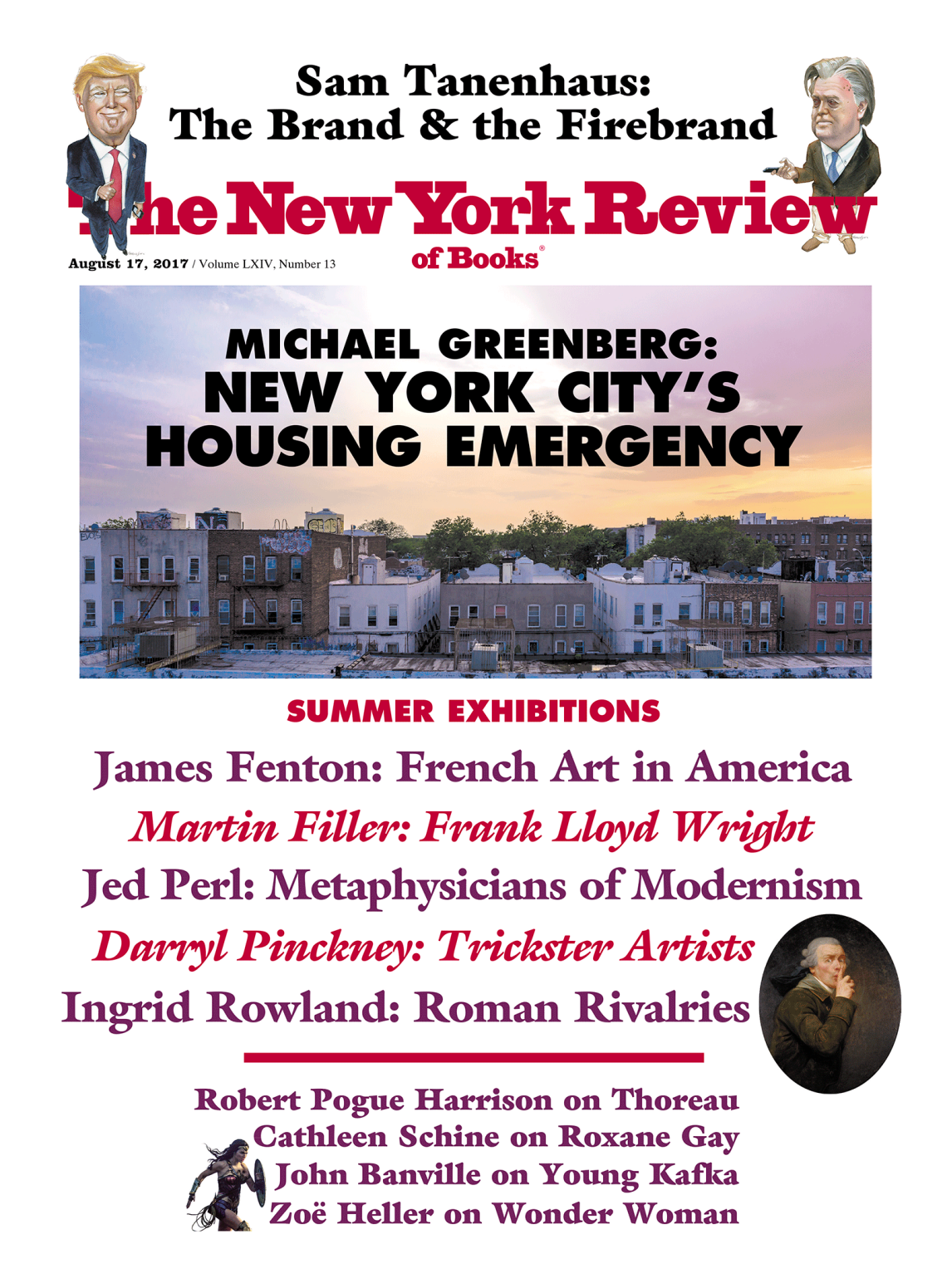

In a recent exhibition at the Sean Kelly Gallery, “Trickster,” Wiley’s subjects weren’t black youths he spotted on the street who remain anonymous, but eleven fellow black artists: Derrick Adams, Hank Willis Thomas, Nick Cave, Carrie Mae Weems, Kerry James Marshall, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Yinka Shonibare, Wangechi Mutu, Glenn Ligon, Rashid Johnson with Sanford Biggers, and Mickalene Thomas. The title, “Trickster,” refers to the cultural hero in black folklore who survives or triumphs through cunning and skill. A trickster is ambiguous and can also change shapes, take on new identities.

Wiley is not coy and has always identified the Old Master—and sometimes later—models for his paintings. For instance, in this show he tells us that his painting of Yiadom-Boakye is after George Romney’s portrait of Jacob Morland of Capplethwaite (1763). Her hunting clothes and boots are not like Morland’s, but she is showing off the same rifle, and the background of pasture and family seat in the distance is also the same. Morland is posed with a hound, but she stands at her edge of the wood with five dead brown rabbits at her black boots. The rabbit is a trickster figure in both African-American and American Indian folklore. Then, too, the bold expression Wiley gives Yiadom-Boakye behind thick black-framed glasses fits the trickster character.

The portrait of Rashid Johnson and Sanford Biggers is subtitled The Ambassadors, after Holbein. Wiley has changed his figures’ postures: here, one of the artists is standing, his hand on the shoulder of the other, who is seated (in Holbein’s painting, the pair is leaning against a display of objects that speak of learning). But the green brocade curtain behind Holbein’s guys is behind Wiley’s as well, and the carpet draped over the shelf in Holbein is the one that Wiley’s barefoot, black-trousered figures are standing on. The clothing in Holbein is sumptuously painted and the same could be said of the loose, salmon-colored shirts that Wiley’s subjects are wearing.

References to the trickster in other cultures, like Reynard the fox, also appear in these paintings. Each canvas contains clues that point to the originals, and not necessarily to the works of the artist-subjects. Some are not as easily read as others, such as the portrait of an inscrutable Glenn Ligon as Hermes. Those are loafers, not winged sandals, so what is the frog he’s holding down on his knee? A terrific amount of painting is going on in these works, especially so, for example, in the details of the dress Carrie Mae Weems is wearing, posed with her back to the viewer, looking over her left shoulder. It is a virtuoso performance. Wiley has a great deal of humor and easy command. His subjects are rendered con amore, as Italians used to say of the best portraits.

Wiley depicts Kerry James Marshall as Lectura, in a triple portrait reminiscent of Van Dyck’s of Charles I. But is Marshall not much darker in skin tone than Wiley has painted him? And taking all the David-sized paintings together, isn’t every subject the identical high-affect brown color? Wiley’s revisions of what is called the canonical are a trickster’s art. Conversation with the past is for him essential. Neoclassical and Romantic painting were both about manipulating reality, Wiley said in an interview, as if to say, why shouldn’t his be?

It almost feels as though an Occupy High Art movement is happening. Black people changed the image of the black in Western art through what they were doing in the other arts and in the outside world. Perhaps instead of removing a statue of Robert E. Lee from a square in New Orleans, instead of appeasing justified feelings of anger at Confederate history, a black artist of Kehinde Wiley’s stature should be commissioned to do a public work in reply to that history.

These cultural sensitivities are not frivolous. How black people have been seen in history continues to influence how they are seen today. Yet the high visibility of blacks in the art world hasn’t done away with the critical defensiveness that made the controversy at this year’s Whitney Biennial over Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till such an embarrassing turf war among the second-rate. Till, age fourteen, was beaten to death in 1955 in Mississippi for supposedly having whistled at a white woman. The painting has no power unless, or until, you think of the horrific image of Till in his open casket on which it was based. Till’s mother gave Jet permission to photograph him so that everyone could see what he had suffered. Some people protested that Schutz, a white artist, had appropriated or was exploiting the pain of the black experience. But James Baldwin defended William Styron’s freedom to write The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), a very misguided novel about slave rebellion.

The most dramatic element in what is going on culturally may be that the image of the black is undergoing yet another change as a symbol. Put a black body up there on the canvas—not a light-skinned body but a dark one—and the work has immediate meaning, or seems profound, or to be a protest of some kind, an example of what Wiley has called the “weaponized aesthetic.” Maybe it has to do with what Black Lives Matter has revealed about black bodies: that they are still subject to racist violence. Even as vessels of desire they earn respect because of what they have been through historically, these young bodies.

-

*

The Image of the Black in Western Art Project was conceived in the 1960s by John and Dominique de Menil. David Bindman joined Henry Louis Gates Jr. as general editors for the completion of the series by Harvard University Press. The earlier volumes have been republished and now ten books of informative essays and beautiful illustrations move through the history of the representation of blacks in the art of the West, from the pharoahs and the fall of Rome to the present. ↩