Half a century has passed since the shocking disappearance of Otis Redding at age twenty-six, when the twin-engine Beechcraft carrying him and most of his touring band the Bar-Kays to a concert crashed in a Wisconsin lake on December 10, 1967. For many who were around then, the time elapsed has not alleviated the shock. The subtitle of Jonathan Gould’s new biography, An Unfinished Life, properly acknowledges the pang of lost possibilities that accompanied that news bulletin. It came at a time of much violence and protest against violence, and was followed soon enough by further catastrophic losses. In the midst of all that, it was hard to give any meaning to Otis’s death beyond random bad luck—although that didn’t stop the inevitable rumors of conspiracy and murder for political or financial reasons.

It wouldn’t have been the Sixties without such rumors. By that point, paranoid distrust was well on the way to becoming the culture’s new mental wallpaper. Buffalo Springfield’s “Paranoia strikes deep,/Into your life it will creep” (“For What It’s Worth,” released January 1967) had sounded the note early, and by year’s end the benign ecstasies of the Monterey Pop Festival, where Otis had performed so triumphantly in June for what he addressed as “the Love Crowd,” were a rapidly curdling recollection. Upon his death, the qualities his fans tended to associate with Otis Redding—his humor, his passionate forthrightness, his delight in the dynamics and textures and constantly evolving grooves of his music—at once belonged to a moment definitively passed.

We played those albums—The Great Otis Redding Sings Soul Ballads (1965), Otis Blue (1965), The Soul Album (1966), Dictionary of Soul (1966)—every day in rotation, because their open-spiritedness made rooms more livable and walls less inclined to close in. He suggested a fortunate temperament, not inclined to pettiness and incapable of fake solemnity; able to express pain and frustrated longing with nothing of self-pity, and then turn it around—sometimes in the same phrase—into a mood of free-flying elation. In the absence of any very specific information it was all that easier to make a culture hero of him.

We knew his roots were in rural Georgia, if not from liner notes then from “Tramp,” his 1967 duet with Carla Thomas. Carla: “You know what, Otis? You’re country! You’re straight from the Georgia woods!” Otis: “That’s good!” Impossible to miss the unimpeachable knowledge that in “Chained and Bound” he brought to the lyric: “Taller than the tallest pine,/Sweeter than a grape on a vine.” There hadn’t been time to find out much. His whole publicly known career, starting from the breakthrough August 1962 session at the Stax studios in Memphis where he first recorded “These Arms of Mine,” had lasted five and a half years. His published statements amounted to little more than a couple of interviews in Melody Maker and Hit Parader.

Those who didn’t have the opportunity to catch him live could only go by whatever his voice was telling. Every first encounter was a matter of registering that this was a voice that sounded like no one else’s. The timbre alone seemed to resonate among echoing interior corridors, never mind his capacity to modulate it through shades of roughness and sweetness, keening and crowing, sliding and deflecting and sharpening. The eccentric swerves of the phrasing, the quicksilver embellishments of tone or timing offered continual astonishment. He stood by himself even in an era when he was being judged in comparison with (for starters) Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye, James Brown.

If he stood for anything it was the pleasure of inventing, of finding an unforeseen angle to launch from or land on, of working with the Stax musicians—Booker T. and the MGs, with horn parts by the Mar-Keys—to build forms that took on independent life, the circular coda of “My Lover’s Prayer” or the descending variations at the end of “Good to Me” or the high hog-calling ululation on “Hawg for You” or the meshwork of insistent pounding and jabbing organ chords that almost submerges the outcry coming from deep in the cacophonous mix on “I’m Sick Y’All.” In the prolonged fadeouts there was always some further accent or nuance, a further flight of verbal free association.

It hardly mattered whether he had written the song; what he did to “Tennessee Waltz” or “Satisfaction” was another and radical form of composition. “Always think different from the next person,” he told Hit Parader. “Don’t ever do a song as you heard somebody else do it.” That sheer difference was the first overwhelming fact. Too different for Top 40 radio in the beginning: it would take all of those five years to make much of a dent at the top of the charts, and only posthumously did he achieve his first million seller, “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay,” the beginning of a fresh phase of experiment stopped in its tracks.

Advertisement

Jonathan Gould has written an absorbing and ambitious book about a life cut short, a life devoid of the melodrama and self-destruction that enliven the biographies of so many of Otis Redding’s contemporaries. He was far from an overnight success, but from the moment he began pushing toward a musical career—as far back as his formation, with some childhood friends, of a gospel quartet calling themselves the Junior Spiritual Crusaders—he moved only forward. He lived by his own precept: “If you want to be a singer, you’ve got to concentrate on it twenty-four hours a day. You can’t have anything else on your mind but the music business.” He soaked up every musical influence in his vicinity, from gospel to R&B to country and western. Louis Jordan’s humorous calypso hit “Run, Joe” (1948) was a childhood favorite, and it’s fun to imagine the seven-year-old Otis singing it, undoubtedly in perfect pitch and with total mastery of Jordan’s version of a West Indian accent. As a teenager he won the local talent show at the Hillview Springs Social Club in Macon, Georgia, so many times they wouldn’t let him win anymore.

He sang lead with a succession of local bands, traveled to Los Angeles where he made his first recordings, and mastered the styles of Clyde McPhatter, Jackie Wilson, Ben E. King, Ray Charles, and above all his fellow Maconite Little Richard. His capacity for mimicry was such that in LA he was able (in a practice not unique at the time) to go out on gigs impersonating the Motown artist Barrett Strong, whose “Money” was a huge hit but who was not known to West Coast audiences. The intense focus of this apprenticeship period can be gauged from Otis’s first Stax recordings. Early influences, Little Richard’s especially, linger on, but he can be heard recombining everything he knows to make a sound unmistakably distinct.

From a biographer’s point of view, a recap of his career risks looking like a pattern of steady patient progress toward ever greater artistry and wider popularity. The unqualified admiration and awe expressed in a wide range of testimonials verges on monotony. From family it might be expected, as when his older sister Louise comments: “I always thought Otis was a kind of divine invention, because nobody ever taught him anything; he just knew everything.” But this sort of statement is typical, whether from Grateful Dead musician Bob Weir after seeing Otis at Monterey (“I was pretty sure that I’d seen God on stage”), MGs guitarist Steve Cropper, Otis’s close collaborator at Stax (“Otis Redding was the nicest person I ever met…. He was always working, always on time, always together, loved everybody, made everybody feel great”), or Phil Walden, the Macon R&B enthusiast who became Otis’s longtime business partner (“he may have been the most original, most intelligent person I ever met in my life”).

Gould’s book doesn’t challenge the consensus that Otis Redding was a remarkable and remarkably decent person. In fact it succeeds in making him seem a good deal more remarkable by taking the measure of the historical circumstances he emerged from. The known day-to-day facts of Otis’s short life are only part of the narrative Gould has framed. Those facts take us deep into the minutiae of radio talent shows, fraternity dances, regional disc jockeys, marginal record companies (one of Otis’s early singles came out on the incredibly named Confederate label, complete with battle flag), the whole music industry wilderness of booking agents, song pluggers, personal managers, and miscellaneous hangers-on, a wilderness Otis was apparently able to take increasingly in his stride. But Gould situates these microworlds within a much wider field of action. To do so he often leaves Otis aside for pages at a time, a maneuver he executes with great confidence. None of these excursions are digressions or footnotes; every detail feeds back into the story he is telling.

Gould’s prelude is Otis’s apotheosis at Monterey. He was, along with Jimi Hendrix, one of the only African-American headliners, unknown to most of the audience, and came on stage after midnight to perform a truncated five-song set, backed by Booker T. and the MGs and the Mar-Keys. His show-stopping transmutation of the sentimental pop standard “Try a Little Tenderness” into an accelerating emotional blowout made him, finally, an incontestable sensation. It is everybody’s favorite kind of show business story, the long-deserved sudden incandescent triumph. This one has been told many times, filmed by D.A. Pennebaker, and generally enshrined as a moment to cling to amid the flak and cultural debris of the late Sixties. As so often in pop culture history we find ourselves confronting the same details again, wondering if these shards can still yield any life once they have been installed in a permanent nostalgia exhibit.

Advertisement

Gould sets the tone for what will follow by dollying back into a panoramic establishing shot: “The United States is a vast country, and geography has always played a part in the saga of its popular music.” Within a few paragraphs he evokes large sweeps of territory and time. Ray Charles, Thomas A. Dorsey, Hoagy Carmichael, and Stephen Foster come into the frame. Gould now makes his premise explicit: to understand the significance of what Otis Redding accomplished, “it is necessary to start with an understanding of the cruel and seemingly unyielding constraints of the culture, musical and otherwise, that was being broken through.” That eloquent phrase—“cruel and seemingly unyielding constraints”—sets up the counterforce to illuminate the apparently effortless freedom of Otis Redding’s aesthetic. The book becomes the story of how he resisted constraint and pushed back against cruelty, in his own fashion and in the terms of his own art.

That story will be told, but Gould makes good on his premise by first reviewing the history of popular music in America, encapsulating the nineteenth-century rise of white blackface minstrelsy and then, after the Civil War, of the black minstrelsy that provided an early professional outlet for African-American performers—and then going on to address the general history of the post-Reconstruction South, the culture of lynching, the myth of the Lost Cause, the economy of sharecropping, the social and racial hierarchies of the towns and cities of the industrialized “New South,” the impact of technology (by way of phonographs, battery-powered radios, and roadside jukeboxes) on the dissemination of information and musical styles. He moves rapidly and lucidly through a wide range of events and allusions, landing for a moment on “Swanee” (1919), George Gershwin’s jazzed-up nod to Stephen Foster’s evocation of the “Swanee River,” mentioning that “Al Jolson happened to hear Gershwin play it one night in a Harlem bordello,” and then slipping back to 1918 to linger on the details and circumstances of the torture and lynching of a pregnant woman in Brooks County, Georgia, “near the headwaters of the actual Suwannee River.”

Into this larger picture Gould introduces Otis Redding’s grandmother Laura Fambro, born in 1877 to ex-slaves in Monroe County, and traces the pattern of her life, as far as it can be known or surmised, in the cotton counties of Georgia. (Surmise plays a large role, especially since whatever papers and photographs had been handed down in the family were destroyed in a fire in 1959.) “In the eyes of southern society,” he notes, “the production of cotton was the only reason for people like the Reddings to exist.” He details the exploitation of sharecroppers and the mechanisms of social control hemming them in because, however familiar it ought to be, this forms part of a story “that the great majority of Americans have always been determined to dismiss, forget, or ignore.”

The astonishment of Otis Redding’s career cannot be grasped without a full sense of the ingrained, fear-driven, stifling forces intended to prevent such an emergence from ever happening. Gould takes time therefore to track the family as closely as possible, from well before Otis’s birth, as the widowed Laura and her three sons, three daughters, and four grandchildren move about Georgia in response to changing economic conditions, finding themselves by 1930 in “a three-room cabin on a stretch of unpaved highway” in a corner of Terrell County (later known to civil rights workers, we are told, as “Terrible Terrell”).

After Otis Redding’s birth in late 1941, his family moved to the booming city of Macon, a transportation hub and manufacturing center with a newly built Army Air Force depot and training school. This relocation from the back country to the industrial commotion of the war economy, from a sharecropper’s cabin to a federally funded housing project, must also have been a dislocation. The history of Otis’s family until then had unfolded in a rural universe where, as Gould notes, “their interactions with whites had been few and far between.” In Macon, daily life involved constant small negotiations and tacit estimations around precisely which lines were not to be crossed. As Otis, still on the fringes of his life as a performer, grew to be a man of great charm and commanding stature, he proved adept at turning such negotiations to his advantage, at least by the standards of a time when music business contracts were exploitative almost as a matter of course.

Otis Redding’s story is not one of unusual trauma or deprivation. He came from a tightly knit family bound by strong beliefs. His mother, Fannie, is briefly but vividly described by his older sister as “what you call a natural woman. She didn’t believe in makeup. She didn’t drink. She didn’t believe in dancing.” His father, Otis Sr., was something of a reformed character—presumably under Fannie’s forceful influence—who ended up as a church deacon and liked to affirm that “poor is nothing but a state of mind.”

Otis, who dropped out of high school and ran with a local gang, some of whom toted guns and edged into criminal ways, might early on have seemed adrift, but everything suggests that he maintained a powerful sense of direction at each step of the musical career he began to build from whatever openings Macon could offer. In the world of 1950s Macon, even the most casual and small-scale interactions often impinged on hidden pressures and unexpressed taboos. The grace with which he moved through such obstacles might make his progress look easier than it ever could have been.

With Phil Walden, the young white R&B fan with ambitions as a booking agent, Otis established a close partnership that would also involve Walden’s younger brother and their father, a prominent Macon businessman. Gould parses the evolution of this partnership in almost novelistic detail. The Waldens become prime embodiments of the struggle of some white colleagues, whether in Macon or later in Memphis, to come to terms with their own heritage of white supremacism. (“My father was born and bred as a racist, as all of his contemporaries were,” Phil Walden remarked. “Otis really taught Daddy a lot about being human.”) This is however by no means a feel-good story about mutual understanding painfully achieved. Gould goes into great detail about wrongheaded presumptions and wishful self-congratulation on the part of some who felt they had done Otis a favor by assisting his career, when the favor—of letting others share the profits of his talent—ran quite the other way.

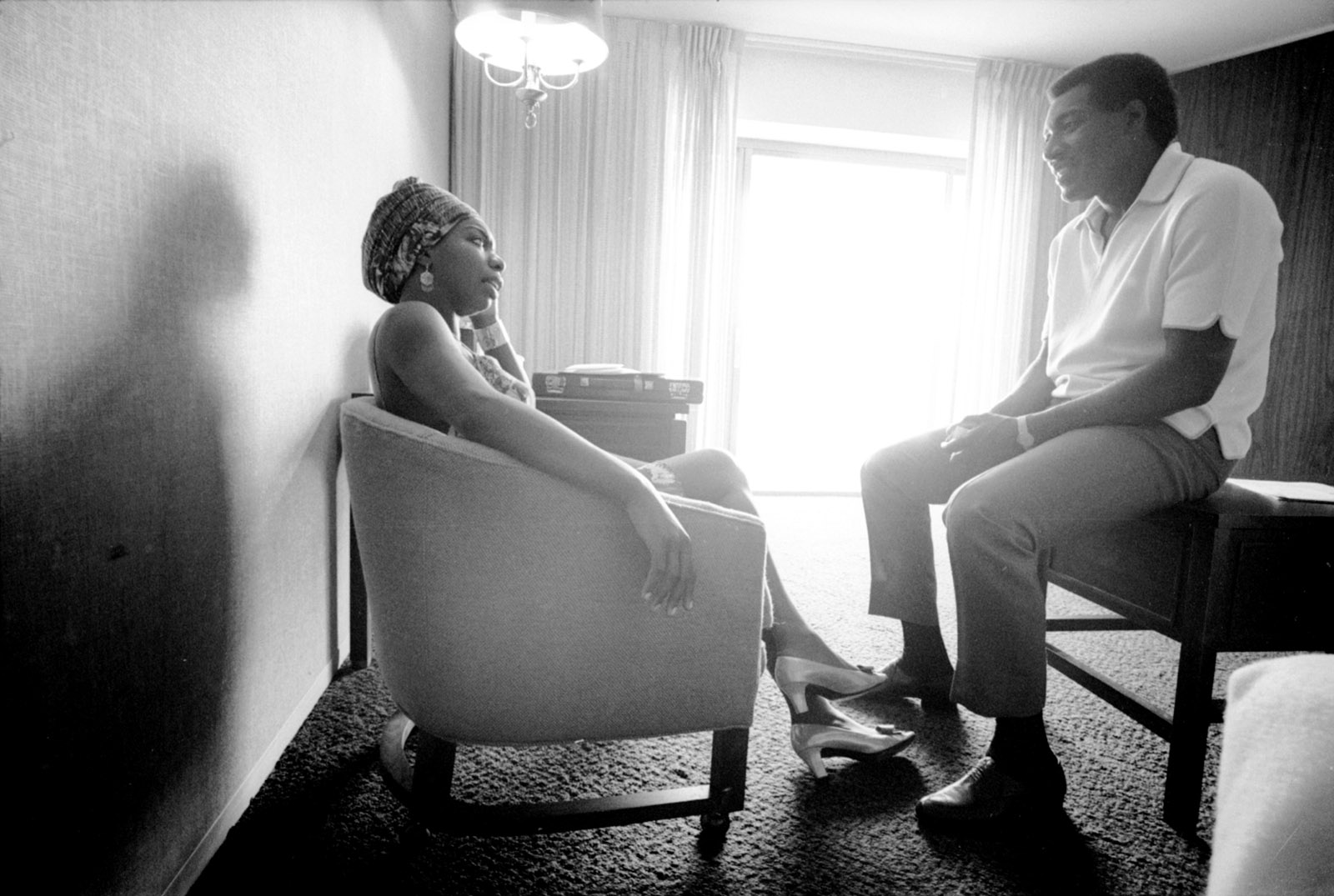

As Otis’s celebrity extended far beyond Macon, with his name being dropped by John Lennon and Mick Jagger and Bob Dylan, he remained closely tied to the city and the region. Having achieved a success that would have allowed him to live wherever he wanted, he didn’t choose to move to larger cities, although by then he had spent years performing in New York and Los Angeles and Chicago and, more recently, London and Paris. He determined rather to go back to the deep country his parents had left behind, buying a 270-acre property remote even from Macon, in an underpopulated area near Round Oak, Georgia, having carefully sounded out nearby white residents and determined that he would not be unwelcome, and settling with his wife, Zelma, and their children at the “Big O Ranch.” A publicity photo of him on horseback on a wooded path, taken a few months before his death, seems far removed from a professional life that had consisted for five years of relentless touring interrupted only occasionally by intensely compressed recording sessions.

It is astonishing to realize what a relatively small percentage of Otis Redding’s time was devoted to making the records that preserve his art. Once he had cut his first hits for Stax—“These Arms of Mine” in 1962, “Pain in My Heart” a year later—he was mostly on the road. His new celebrity took him to the famous theaters whose names he would tick off in his wonderful version of “The Hucklebuck”: the Royal Peacock in Atlanta, the Harlem Square Club in Miami, the 5-4 Ballroom in Los Angeles, the 20 Grand Club in Detroit, the Howard in Washington, D.C., the Apollo in New York. As his fan base expanded to include white hipsters and rock celebrities, he cut a live album at LA’s Whisky a Go Go before embarking as the headliner of the Stax-Volt Revue on an enthusiastically received European tour. (A video of an Oslo concert in April 1967 is a remarkable record of the occasion.)

In near-continuous touring he evolved from a physically restrained performer focused on producing those formidable vocal tones—he was, famously, not much of a dancer—to someone who dominated a stage, extracting theatrical power from songs like “Try a Little Tenderness” and ratcheting up the tempo on numbers like “I Can’t Turn You Loose” to the point where even the MGs had trouble keeping up. The live recordings are often magnificent, but it was in the Stax recording studio that he did his greatest work. Perhaps being reunited for brief intervals with the MGs and the Mar-Keys, after touring with other musicians, provided the adrenaline that made it possible to record a masterpiece of an album such as Otis Blue in less than forty-eight hours, with the musicians taking time out in the middle of the session to go play their usual local gigs.

In the live recordings Otis works the audience with overpowering energy. In the studio he sings to the other musicians—and to himself, seeming to surprise himself with the effects as he creates them. He takes apart the lines of songs and breaks them into fragments that he holds up and examines to savor their newly revealed power. The rapport he elicited from Booker Jones, Steve Cropper, and the rest has been amply attested to; just listening to the records is testimony enough. (Among the great pleasures of Gould’s book are his very considered assessments of each of Otis’s albums, track by track.) Beneath everything is the duet he maintains with the MGs’ great drummer Al Jackson Jr. Otis is never “backed” by the musicians; he’s in the middle, responding and directing. Unable to read music and not a virtuoso on any instrument but his voice, he was able by singing the parts to organize complex instrumental arrangements that might be recorded on the spot. The Stax sessions for the most part did not involve overdubbing or splicing fragments together; they were assembled in place and recorded in real time.

A final note on lyrics: Otis was known for his casual approach to the words of songs, improvising new lyrics for his version of the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction” and, in Gould’s view, botching Sam Cooke’s final masterpiece “A Change Is Gonna Come” by garbling the narrative. For Gould, it was only gradually that Otis fully appreciated the importance (commercially as well as aesthetically) of lyrical coherence, an appreciation evident in the control of “The Dock of the Bay.” On the other hand, what Otis did with language right from the beginning was central to his art: those elisions, unexpected emphases, distortions, those diminutives that enlarged (“a little pain in my heart”), those inspired bursts of nonsense and sound effects marking the very edge of language and seeking to go beyond it. Language was only one of the things he was always taking apart and putting back together again, differently.