In January 2011, just before the beginning of the spring semester, Daniel Mendelsohn—well known to readers of The New York Review and a professor of classics at Bard College—was approached by his eighty-one-year-old father, a retired research mathematician and instructor in computer science. Could he, Jay Mendelsohn asked his son, “for reasons,” Daniel writes, “I thought I understood at the time,” sit in on his annual freshman seminar on Homer’s Odyssey? Nervously, Daniel welcomed this unexpected auditor, believing, as he was assured, that the old man would be happy just listening. Before the first session was over he had realized his mistake and was thinking: This is going to be a nightmare. In fact the paternally augmented seminar, and the Odyssey-related Mediterranean cruise that father and son took shortly after it, turned out to be an unexpected, and revealing, success. In particular, they stimulated exploration, via Homer, of the timeless elements of family relationships down through the generations.

About a year after the seminar, Jay Mendelsohn suffered the fall that unexpectedly led to his final illness. The unusual, and unusually complex, nature of the book before us is previewed, and explained, in a meditation that its author recounts in its early pages of watching over his unconscious father, “as imperturbable as a dead pharaoh in his bandages,” in the local hospital’s intensive care unit:

But we had had our odyssey—had journeyed together, so to speak, through this text over the course of a semester, a text that to me, as I sat there looking at the motionless figure of my father, seemed more and more to be about the present than about the past. It is a story, after all, about strange and complicated families, indeed about two grandfathers—the maternal one eccentric, garrulous, a trickster without peer, the other, the father of the father, taciturn and stubborn; about a long marriage and short dalliances, about a husband who travels far and a wife who stays behind, as rooted to her house as a tree is to the earth; about a son who for a long time is unrecognized by and unrecognizable to his father, until late, very late, when they join together for a great adventure; a story, in its final moments, about a man in the middle of his life, a man who is, we must remember, a son as well as a father, and who at the end of this story falls down and weeps because he has confronted the spectacle of his father’s old age.

The sight of his infirm father is so overwhelming to Odysseus that he, a congenital liar and expert storyteller, abandons his manipulative tales and “has, in the end, to tell the truth. Such is the Odyssey, which my father decided he wanted to study with me a few years ago; such is Odysseus, the hero in whose footsteps we once travelled.”

What are we to make of this remarkable declaration? In the first instance, obviously, that anyone embarking upon this fascinating book would be well advised to read, or reread, the Odyssey first, since Mendelsohn’s exploration is at least as much a personal family memoir as a critical report on Homer’s epic, and the two facets of the book are by no means always related, despite the surprising ways they frequently illuminate each other. But we have here also, understandably, a partial and selective reading of Homer that concentrates on familial relationships above all else, sometimes sees these in a way that may surprise the experts (for example the description above of Odysseus’s reunion with his father, Laertes—what’s the point, now the suitors are dead, of yet another otiose cover story, not least one causing uncalled-for distress?), and attributes to the ancient text illuminations that more plausibly derive from modern reflection.

Daniel, as his meditation makes very clear, this time around is not only teaching the Odyssey but using it as a psychological key to unlock the personality of a father he feels he has never really understood: this odyssey only makes sense as a quest for emotional understanding. We can see how the alleged parallels assist him, but we also can’t help noticing how the discoveries he makes and mysteries he solves emerge not from Homer, but rather from his persistent questioning of his own family—various Mendelsohn uncles, cousins, brothers, and close acquaintances.

Thus we learn a good deal about the members of the extensive and tightly woven Mendelsohn clan, and in the process one or two striking Homeric likenesses are indeed established, most particularly that of Daniel’s maternal grandfather, who is remembered as vain, talkative, and a great trickster, and had four marriages but only one son: the alert Homerist will at once be reminded of Odysseus’s maternal grandfather Autolycus, and the repeated one-son pattern of Odysseus’s own family. Jay himself comes across initially—as he has long seemed to his son—as an impatient man of dogmatic opinions that too frequently recall the clichés of his professional class and generation. He believes in firm definitions (“x is x,” “Only science is science”) and the virtues of hard work, the more difficult the better; he’s suspicious of emotionalism. He and his devoted wife, Marlene—housebound, but witty, cheerful, fun-loving, extrovert: a fine teacher, and this book’s dedicatee—are classic opposites in all respects, an arrangement that seems to work well.

Advertisement

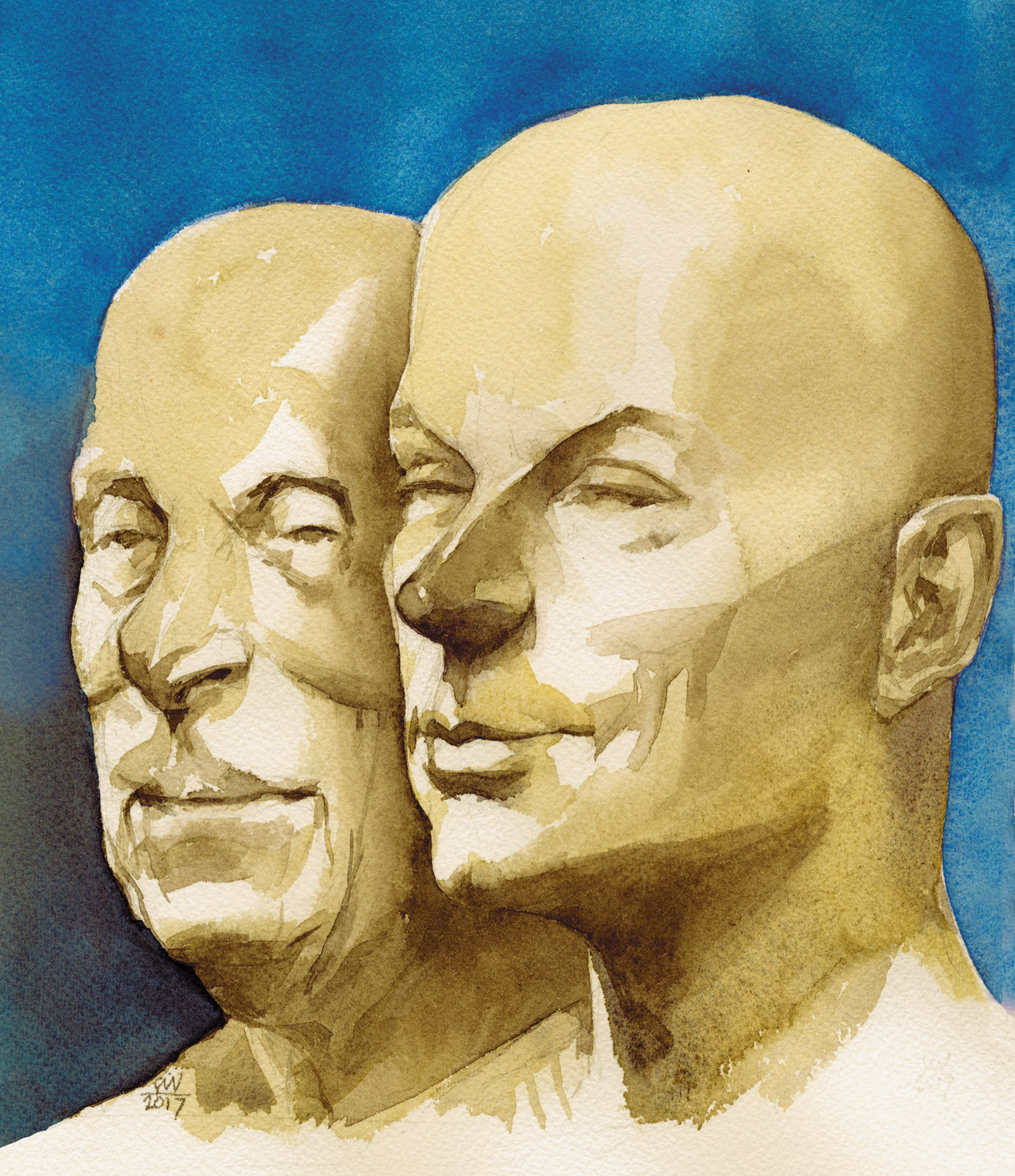

Like the vagrant Odysseus, Jay has a large, bald cranium (to the young Daniel he seemed “all head”). On his trips to Bard he sleeps on the narrow bed that he had, years earlier, carpentered for Daniel after he outgrew his crib; it had been doubling as a sofa in Daniel’s study. Father and son, like Odysseus and Penelope, share a bed secret: just as Odysseus built their bed around a bedpost made from an immovable vine, so Jay had made Daniel’s bed from a door.

Daniel, who has no real grasp of mathematics, appreciates, but is nervous about, his father’s dictates: “It’s impossible to see the world clearly if you don’t know calculus.” Yet Jay, who gave up Latin as a schoolboy, does, grumblingly, take note of his son’s response: neither can you see the world clearly without knowing the Aeneid. In consequence father and son come appreciably closer by tackling bits of Virgil together over the phone. As the Latin finally gets too difficult for Jay, he disarms his son by saying: “It’s okay. Now you’ll read it for me.” And hard as Jay may be, no one could have been more understanding when, as a confused adolescent, Daniel came out to him as gay.

The seminar, of course, has a wider reach than the Mendelsohn family, so as we enter the classroom the focus broadens. We are always conscious of Jay, small, bald, quietly aggressive, week after week in the same seat by the window, a little apart from the rest, coming out with some arresting and essentially nonliterary comment: apropos Odysseus and Penelope’s marriage, on the shared “little things that nobody else knows about”; on Telemachus, “He proves he’s a grownup by taking responsibility”; and, most unforgettably, on Achilles’s confession in the Underworld—a complete negation of his Iliadic social code—that he’d rather be a living hired field hand than rule as king of the dead: “It reveals that you can spend your whole life believing in something, and then you get to a point when you realize you were wrong about the whole thing.”

Like most readers, Mendelsohn’s students, and his father, are puzzled by a work that presents its presumptive hero at the outset only briefly, offstage, as a castaway on a remote island. The victim of the angry Poseidon, Odysseus is rescued by a sexy nymph: after living with her for seven years, he is now miserably yearning for wife and home but seems incapable of doing anything about it. He’s lost all his men and ships, Jay keeps complaining; he cheats on his wife. What kind of a hero is that? Further, he is left there in limbo until Book 5, awaiting the gods’ decision to bring him back.

Books 1 and 2 describe, in arresting detail, the situation in his island kingdom of Ithaca: local government is in collapse, while a bunch of young aristocratic hooligans, convinced that the long-absent King Odysseus is dead, have invaded his house (on the excuse of courting his presumed widow, Penelope) and are living riotously, consuming his goods and swilling his wine. There is, clearly, not much that Penelope and her near-adult son, Telemachus, can do about the situation. Mendelsohn’s students don’t get a chance to analyze Homer’s sharp-edged portrayal of a society enduring the prolonged absence of its leaders during a foreign war, since they are being treated to a lecture on the Homeric question: Were the two epics attributed to Homer the work of a single person, or did they evolve orally through many bards, by a process described by Mendelsohn as composition-in-performance?

These students also, understandably in view of their age, seem a little shy on the subject of Telemachus’s “adolescent oscillation between awkwardness and braggadocio,” his bursts of rudeness to his mother (he clearly finds her unwashed and unlaundered state of mourning distasteful), and his tearful aggressiveness in confronting the suitors. But they emerge as shrewdly perceptive when it comes to Books 3 and 4, which describe Telemachus’s visits to Pylos and Sparta seeking news of his father. As they see at once, the societies of both Nestor and of Menelaus and Helen—peaceful, settled, observing religious and domestic customs—are drawn in deliberate contrast to the anarchic conditions that Telemachus has left behind in Ithaca.

Advertisement

By now, however, we also have to consider the numerous divine intrusions into the story by the goddess Athena, who not only sends Telemachus off on a journey in search of his father—even assuming his likeness to organize his departure—but again and again intervenes to help both father and son (Odysseus is her particular favorite) in moments of crisis. It is hard not to sympathize with Jay’s reiterated complaint that Telemachus and Odysseus are just following orders, that the gods do everything for them, that life isn’t like that.

When Odysseus finally returns to Ithaca, the seminar becomes preoccupied with the literary proposition that he needs to be alone to be a proper hero. There is also the question of whether a real hero can cry. This misses the forceful display of Odysseus’s physique, prowess, and seductive masculinity, which are stressed from the first moment of his appearance in Book 5. He fells twenty trees, builds a raft in four days, and steers it effectively by the stars. All his helpers—Calypso, Athena, the sea-nymph Ino, the Phaeacian princess, Nausicaa, and finally Nausicaa’s mother, Queen Arêtê—are female. He appears in front of Nausicaa and her handmaidens like a mountain lion, naked except for a leafy branch, and the verb that describes his “mingling” with them, mixesthai, is also a term for sexual intercourse. Tactful, clever, and prepossessing, he has not been talking to Nausicaa’s father, King Alcinöos, for five minutes before the king declares he would fancy him as a son-in-law. The helpless castaway has been neatly transformed into a prize catch—a hero indeed.

Mendelsohn discourages his students, on literary grounds, from arguing that the off-the-map wanderings with which Odysseus regales his Phaeacian hosts (his sojourns among the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis, the Lotus-Eaters, Circe, and so on) are imaginary. As Daniel’s old teacher Jenny Strauss Clay—consulted on this point—reminds him, Circe is mentioned, by the narrator, i.e., Homer, as having taught Odysseus a special knot: ergo, she, and everything connected to her, must be regarded, for the Odyssey, as real, not fictional. But Odysseus does frequently tell fictitious stories about himself (often posing as a Cretan, which reminds us, with mischievous intent, of the old saying that all Cretans are liars). Furthermore our Odyssey was put together in a period, the seventh century BCE, that saw not only the expansion of physical horizons, through commerce and exploration, but also the dawn of scientific rationalism. The old mythical frontiers of the Mediterranean—including the encircling Ocean and the Underworld—were everywhere being challenged, and an entire fabric of belief with them. When beyond-the-horizon myths like those of the Sirens or the Wandering Rocks were being supplanted by less colorful geographical fact, it is quite possible that our composer hedged bets on the authenticity of such tales by having Odysseus, their self-proclaimed protagonist, narrate them, leaving everyone, including the Phaeacians, to decide for themselves whether he was telling the truth or, as so often, fabricating a tall tale for the pleasure of it.

This kind of historically conscious scrutiny is not what we get in Mendelsohn’s seminar, which covers ground familiar to all teachers and college freshmen. Beyond discussion of the Homeric question, the class does not, for instance, take up issues of transmission and sourcing for the three-thousand-year-old text as it is parsed and analyzed to establish character and motivation. Differences from modern thinking are noted. Timeless similarities, not least of psychology and behavior, are weighed as proof of greatness. In the hands of a clever and imaginative teacher, as here, the method has considerable merit, even though by its very nature it tends (as, again, here) to ignore improbabilities of plot, of which the Odyssey contains several particularly egregious examples. How can Odysseus kill, almost single-handed, over a hundred suitors? (Answer: originally, there seem to have been only a dozen.) And why does Menelaus have to wander around the eastern Mediterranean for seven or eight years after the war? (Answer: in order to avoid getting home before the murder of his brother Agamemnon is avenged by the latter’s son, Orestes; otherwise everyone would wonder why Menelaus hadn’t done the job himself.)

The Odyssey cruise, wished on Mendelssohn and his father by another of his former teachers, Froma Zeitlin, paid off in surprising ways, despite the fact that the Sicilian and Italian sites visited were mostly the improbable suggestions of Greco-Roman savants desperate to maintain that the myths retold by Odysseus had a solid factual origin. Though Jay begins as expected, ready for a serious educational experience backed up by the actual Homeric locations, he finds the sites disappointing (at Troy he decides that “the poem feels more real than the ruins”) and, to his son’s astonishment, mellows socially at sea, singing old songs from the 1930s and making unlikely friends over the martinis. All this leads Daniel to wonder—having already been taken aback to learn, post-seminar, from his students how much they’d been enjoying Jay’s company on their train journeys home—“How many sides did my father actually have, and which was the ‘real’ one?”

What most moves Mendelsohn at the end of the Odyssey is the image of son, father, and grandfather standing triumphantly together, the suitors slaughtered, present and past “juxtaposed in a single climactic moment.” The enlightenment he gains often comes not directly, but by associative suggestion, reflecting on “long journeys and long marriages and what it means to yearn for home.” Jay’s bluntness and inflexibility, we come to see, conceal anxieties and sympathies as well as enduring (though secular) Jewish principles. His passion for education and hard work, his appreciation for solidity and authenticity, are just those qualities that led his son to pursue the rigors of classical philology. Yet for whatever reasons—several are suggested—somehow Jay never completed, and indeed may never have begun, his Ph.D. dissertation in mathematics, and a strong recommendation from his commanding officer that he go to West Point and train as an officer came to nothing. Some human mysteries never get solved.

There are many moments to cherish in this tangled and passionate investigation. The discussion of the Odyssey, if narrow in some respects, sparkles, and the seminar was lucky in its students. (I shall not forget in a hurry the suggestion of one that Telemachus may unconsciously hope that his long-absent father is dead, since being expected to love a living stranger would be tougher than continuing to mourn a dead one.) It was a symbolically happy accident—the temporary closing of the Corinth Canal—that prevented the cruise from ever reaching the island that may or may not be Ithaca. This left a whole day without instruction. The captain, recalling that Mendelsohn had translated C.P. Cavafy’s marvelous poem on the value of not hurrying to reach Ithaca—a poem made famous by its recital at the funeral of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis—persuaded him to fill in with a reading of the poem and a lecture on Cavafy. He did, with much of Tennyson’s “Ulysses” as well as Cavafy, and we get a haunting glimpse of it here: the fear that the end of your journey means finis, the hope residual in perpetual postponement, in “the virtues of not arriving.”

But best of all are the various small recognitions that combine to build the late-blossoming intimacy between Jay and his son. Of these the most intensely moving for me was the moment on the cruise at which Daniel, who suffers from intense claustrophobia, hysterically refuses to go into an Italian cave (allegedly that of the seductress Calypso). Jay takes him gently by the hand and not only walks him through what he most fears (“You did good, Dan”) but afterward tactfully explains to other travelers that his son was helping him manage the steep stairs. We recall what he said to his wife when Daniel confessed to being gay: Let me talk to him, I know something about this. Despite his embarrassing table manners and defensively obstinate declarations, this is far from the only matter of real importance that Jay Mendelsohn knew something about. We should all be so lucky as to have had a father like that; and now we can enjoy his son’s honest, and loving, account of the improbable odyssey that gave them this one last deeply satisfying adventure together.

This Issue

October 26, 2017

Rushdie’s New York Bubble

The Adults in the Room

Dialogue With God