Constance Cary Harrison, first seamstress of the Confederate flag, remembered Virginia after the execution of John Brown in 1859. Her family lived far from Harpers Ferry, scene of Brown’s slave uprising:

But there was the fear—unspoken, or pooh-poohed at by the men who were mouth-pieces for our community—dark, boding, oppressive, and altogether hateful. I can remember taking it to bed with me at night, and awaking suddenly oftentimes to confront it through a vigil of nervous terror, of which it never occurred to me to speak to anyone. The notes of whip-poor-wills in the sweet-gum swamp near the stable, the mutterings of a distant thunder-storm, even the rustle of the night wind in the oaks that shaded my window, filled me with nameless dread. In the daytime it seemed impossible to associate suspicion with those familiar tawny or sable faces that surrounded us…. But when evening came again, and with it the hour when the colored people (who in summer and autumn weather kept astir half the night) assembled themselves together for dance or prayer-meeting, the ghost that refused to be laid was again at one’s elbow.

In the savage, undreamed-of slave system in the New World, Africans were physically and mentally subjugated, worked to death, and replaced. Only when the enslaved labor population was maintained by reproduction and not by the importation of replacements were they given enough to eat to sustain life, and that was more than one hundred years after Louis XIV’s Black Codes licensed barbarism in the Caribbean. Black Retribution is the root of White Fear.

Harriet Beecher Stowe tried to portray a Nat Turner–like character in Dred; A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1856), the novel that followed her sensation, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Stowe gives Dred the pedigree of being the son of Denmark Vesey, the leader of a planned slave revolt in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1822. But she turns her Nat Turner into Robin Hood, and he never gets around to his slave uprising, perhaps because Stowe could not bring herself to depict the slaughter of white people at the hands of black people. You could say that Kara Walker’s work begins at the threshold of this resistance to imagining and historical memory. Before John Brown there had been Nat Turner; before Denmark Vesey, the Haitian Revolution; before Mackandal’s Rebellion, Cato’s Rebellion.

In Kara Walker’s exhibition of twenty-three new works, mostly on unframed paper, at the Sikkema Jenkins gallery in New York, it is as though she has drawn her images of antebellum violence from the nation’s hindbrain. Walker has been creating her historical narratives of disquiet for a while, and they are always a surprise: the inherited image is sitting around, secure in its associations, but on closer inspection something deeply untoward is happening between an unlikely pair, or suddenly the landscape is going berserk in a corner. It has been noted in connection with Walker’s cutouts what a feminine and domestic form the silhouette was in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and that because of its ability to capture the likeness of a person in profile it was also a kind of pre-photography.

In a large work of cutout paper on canvas in the exhibition, Slaughter of the Innocents (They Might be Guilty of Something), that tranquil, even sentimental atmosphere of the silhouette gets deranged, disrupted. From a distance, you see a harmonious pattern of big and small human figures, adults in Victorian dress and children, some naked. There are children upside down along the top of the canvas, and the procession of figures seems to be tending to your right in frieze-like spatial orderliness. Then you make out that a black man has hooked a white man by the back of his shirt with a scythe, while two black women seem to be committing infanticide.

“Visual culture is the family business,” Hilton Als notes in Kara Walker: The Black Road (2008). Her father, Larry Walker, is a painter and teaches art, and her mother, Gwendolyn Walker, is a dress designer and seamstress. Born in Stockton, California, in 1969, and educated at the Atlanta College of Art and the Rhode Island School of Design, Walker was criticized by some black artists at the beginning of her career for using what they considered stereotypical black images from the nineteenth century that they claimed spoke primarily to a white audience. But the titles of her early installations of black cut-out silhouettes on white walls more than give the game away: Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994) positions a Gone with the Wind–style romantic white couple so that the man’s back is turned away from the images of black women and their sexual bondage; The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven (1995) finds Stowe’s white lamb of innocence armed with an ax; and No mere words can Adequately reflect the Remorse this Negress feels at having been Cast into such a lowly state by her former Masters and so it is with a Humble heart that she brings about their physical Ruin and earthly Demise (1999) has against a gray background silhouettes of black women’s heads attached to swans’ white bodies.

Advertisement

Of her 2000 installation Insurrection! (Our Tools Were Rudimentary, Yet We Pressed On), in which she projected onto the museum walls cut, pasted, and drawn-on colored gels, Walker said:

Beauty is the remainder of being a painter. The work becomes pretty because I wouldn’t be able to look at a work about something as grotesque as what I’m thinking about and as grotesque as projecting one’s ugly soul onto another’s pretty body, and representing that in an ugly way.

She said she was thinking of Thomas Eakins’s surgical theater paintings as she was also imagining house slaves disemboweling their master with a soup ladle. Beauty? She went on to say that her narrative silhouettes were her attempts to recombine or put back together a received history that has already in some way been “dissected.” But the images emerged from her subconscious, she warned, and she couldn’t necessarily explain their meanings. Her retrospective at the Whitney Museum in 2007 was entitled My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love. As graphic and unmistakable as they often are, what story her images tell as a whole is not easily read. The poet Kevin Young has observed that Walker’s early works were fantasies, however sadomasochistic. But then her work became more obviously related to American history.*

They are foreboding, stealth-like, those silhouettes of black people that haunt a riverbank or slip across newsprint in her 2005 series of lithographs and screenprints, Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated). She takes prints of the engravings or pages from a popular nineteenth-century album-size book that features numerous illustrations of maps, battles, and events relating to the conflict and superimposes on them out-of-scale black figures. The presence of black people as if from another dimension has the effect of being a commentary on the scene to which they have been added. (Another version of the series was done in photo offshoot in 2010.)

In this autumn’s Post War & Contemporary Art sale at Christie’s is a scene from the series called A Warm Summer Evening in 1863, which shows a commotion of men around a house in flames. The caption below—The Rioters Burning the Colored Orphan Asylum Corner of Fifth Avenue and Forty-Sixth Street, New York City—refers to an incident during the Draft Riots of 1863, when poor white men, mostly Irish, who could not buy their way out of the army attacked blacks. One hundred and nineteen people were killed, some two thousand injured. Walker superimposes over the scene the figure of a black girl who has hanged herself with her own long braid of hair. The piece, done in 2008, roughly eight feet across and five feet high, is made of felt on wool tapestry. Maybe a computer told a loom how to weave the image of the engraving. Or was it done by hand? However it was achieved, it is an extraordinary piece of work.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. stresses in Black in Latin America (2011) that most of the kidnapped from the African continent were taken to South America and the Caribbean; only a small percentage went to North America. In the Sikkema Jenkins exhibition, one of the large works, Brand X (Slave Market Painting), in oil stick on canvas, shows a white man lolling in sand, his dick exposed, as if he’d just raped the black woman tied down on her stomach nearby (see illustration above). Around him dance instances of rape and murder. You see a volcano in the distance and the suggestion of a tropical tree. (Cartoon Study for Brand X is an affecting portrait of a black woman, done in oil stick, oil medium, and raw pigment on linen.)

But Walker’s slave history generally refers to the United States. Her exhibition of 2007, Bureau of Refugees, evokes the establishment after the Civil War of the US Bureau of Freedom, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands, for the benefit of displaced white people as well as formerly enslaved black people. She has sometimes projected images in a way that recalls the cycloramas or dioramas of nineteenth-century American exhibition history. The press release for the Sikkema Jenkins exhibition takes off from the American carnival huckster tone:

Advertisement

Sikkema Jenkins and Co. is Compelled to present The most Astounding and Important Painting of the fall Art Show viewing season!

Collectors of Fine Art will Flock to see the latest Kara Walker offerings, and what is she offering but the Finest Selection of artworks by an African-American Living Woman Artist this side of the Mississippi. Modest collectors will find her prices reasonable, those of a heartier disposition will recognize Bargains! Scholars will study and debate the Historical Value and Intellectual Merits of Miss Walker’s Diversionary Tactics. Art Historians will wonder whether the work represents a Departure or a Continuum. Students of Color will eye her work suspiciously and exercise their free right to Culturally Annihilate her on social media. Parents will cover the eyes of innocent children. School Teachers will reexamine their art history curricula. Prestigious Academic Societies will withdraw their support, former husbands and former lovers will recoil in abject terror. Critics will shake their heads in bemused silence. Gallery Directors will wring their hands at the sight of throngs of the gallery-curious flooding the pavement outside. The Final President of the United States will visibly wince. Empires will fall, although which ones, only time will tell.

In an essay in The Ecstasy of St. Kara (2016), Walker says that the Twitter hashtag #blacklivesmatter has become “shorthand for a kind of race fatigue” that comes from the repeated stories of a documented police shooting followed by a protest that then produces no indictments. In a “nihilistic age,” maybe “nothing really matters.”

Her slave history is also that of the US in the pictorial heritage she uses, starting with Auguste Edouart’s silhouettes made during his travels to Boston, New York, and New Orleans. Walker reproduces Edouart’s “John’s Funny Story to Mary the Cook,” from A Treatise on Silhouette Likenesses (1835), in her book After the Deluge: A Visual Essay by Kara Walker (2007), about the crisis of Hurricane Katrina. It shows a black male figure in high collar and tails, a coachman perhaps, in animated monologue to a thickset white woman holding a saucepan and spoon before a hearth. They are human beings, not caricatures.

What might have made some people uneasy about Walker’s work at first was that her black people in silhouette come from the racist caricatures of American illustration. These are not sculptural, aestheticized shades dancing in an Aaron Douglas mural. Black art or black artists were supposed to restore the dignity and assert the beauty of black people. But Walker will deal in exaggerated features and kinky hair, in the black as grotesque. They are not pretty. Elizabeth Hardwick said that when she was growing up in Lexington, Kentucky, in the 1920s, she heard white people say they couldn’t understand why black people would want photographs of themselves. The carnage in Walker’s work asks white people: What’s so pretty about you?

Moreover, for all the violence, her black people are not victims. They are casualties or among the fallen, but not powerless, because her images comprise an army of the unlikely, those grotesques and comics that white people invented in the effort to persuade themselves—and black people as well—that black people were only fit for servitude, and that they were incapable of and uninterested in revolt. Walker turns against whiteness what white people invented. Those funny faces have come back to kill Massa. They aren’t so funny anymore, and Walker’s work in the Sikkema Jenkins exhibition has a wild, retaliatory air.

Some of the new works are very large, and you wonder where she could have found such huge sheets of paper. They are not cartoons (in spite of the title of that portrait of a black woman in headscarf and earrings); they don’t feel as though she means to suggest a studio of preparatory drawings. Black and white, ink and collage on paper, is the finished state. Most of the black figures in these new works are not in silhouette. She has shades of black and gray, hints of yellow, blue, and red, and sometimes there are backgrounds of brown. Walker is a superb draftsman. In the towering Christ’s Entry into Journalism, dozens and dozens of figures spiral out from the center. The black figures—heads, torsos, running men, women in hats—seem to come from different eras and circumstances of black representation, here satire, there ethnography, folklore, over there the black leader, black sports figure, or black singer, and those lips look like they came from Disney’s Jungle Book film, or her neck has that Jazz Age fashion magazine vibe.

I have heard viewers compare Christ’s Entry into Journalism to James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (1888), in the Getty Museum, and Benjamin Robert Haydon’s Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem (1820), in the Athenaeum of Ohio, and maybe so—if the point is that the reactions of spectators depicted in the painting are intended to affirm the reality of the Messiah. In Walker’s painting, the figures swirl around the center: a riot cop, maybe white, is about to bring a chicken leg down on a masked creature; a naked black man who resembles a harlequin has a sword by his side; behind him a Confederate soldier is wielding a dagger. White men rape or sport erections; a white woman brandishes an umbrella; a James Brown–like singer does a move with a microphone; a devil is stealing away a partially mummified black man in a tie; a flapper, not necessarily white, carries on a platter the head of a black youth in a hoodie. But it’s not certain which black figure at the center is the Christ figure: the black man kneeling in chains—the long echo of the design Josiah Wedgwood created for an antislavery medallion in 1787—or the naked black woman being borne away, or even the dark black—mannequin?—with her arm raised in valediction, and an equally dark black man immediately behind her with what looks like a protest sign.

The Pool Party of Sardanapalus (after Delacroix, Kienholz), also very big, has an Assyrian king floating in his cloud, detached from the violence around him. Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus (1827) is sexy; the concubines are nude, and the men killing them are seminude. In Walker’s revision, a naked black man is being stabbed by a white woman in a corset; a white man has his hands on a black man from behind and appears to be urging him to stab the naked black figure in front of him. But the center of Walker’s dynamic composition is a white man’s foot and the ropes around it. You follow the lines out in three different directions to black women in bikinis pulling firmly. Then you find the white man, most of his clothes off, being held down by black women and disemboweled. A naked white man lies with his face in a pool of blood; a black woman in a beach cap berates a white man’s back with a heavy branch. It’s not clear what is going on between the interracial couple at the top; at the opposite end a black youth in a do-rag rests on an elbow and smokes what you hope is reefer, but the whole is fearsomely kinetic, and Walker tells us in the title that she also had in mind something like Ed Kienholz’s sculpture of a policeman beating a black rioter.

Violence is a secret held by swamps in works such as Dredging the Quagmire (Bottomless Pit) or Spooks. Dead bodies are to be violated in Paradox of the Negro Burial Ground, Initiates with Desecrated Body, and The (Private) Memorial Garden of Grandison Harris, a work done in oil stick, ink, and paper collage on linen that refers to the slave trained by the Georgia Medical College to rob graves. Some of the paintings seem to portray how old and tired American racism has become: the rebel flags are as tattered as the laundress is tired, the branches have no leaves, whites and blacks are shoeless, stuck in backcountry folklore. It’s hard to read the expression on the face of a black woman who is washing, rather harshly it seems, the back of a white woman in A Piece of Furniture for Jean Leon Gerome. The article of furniture must be the sculpture of a black head on which the white woman sits. Walker’s response to, say, Gérôme’s Moorish Bath (1870), in which a black woman seems solicitous of a hunched-over white woman, may lie in the aggression with which the black woman in her drawing washes the white woman.

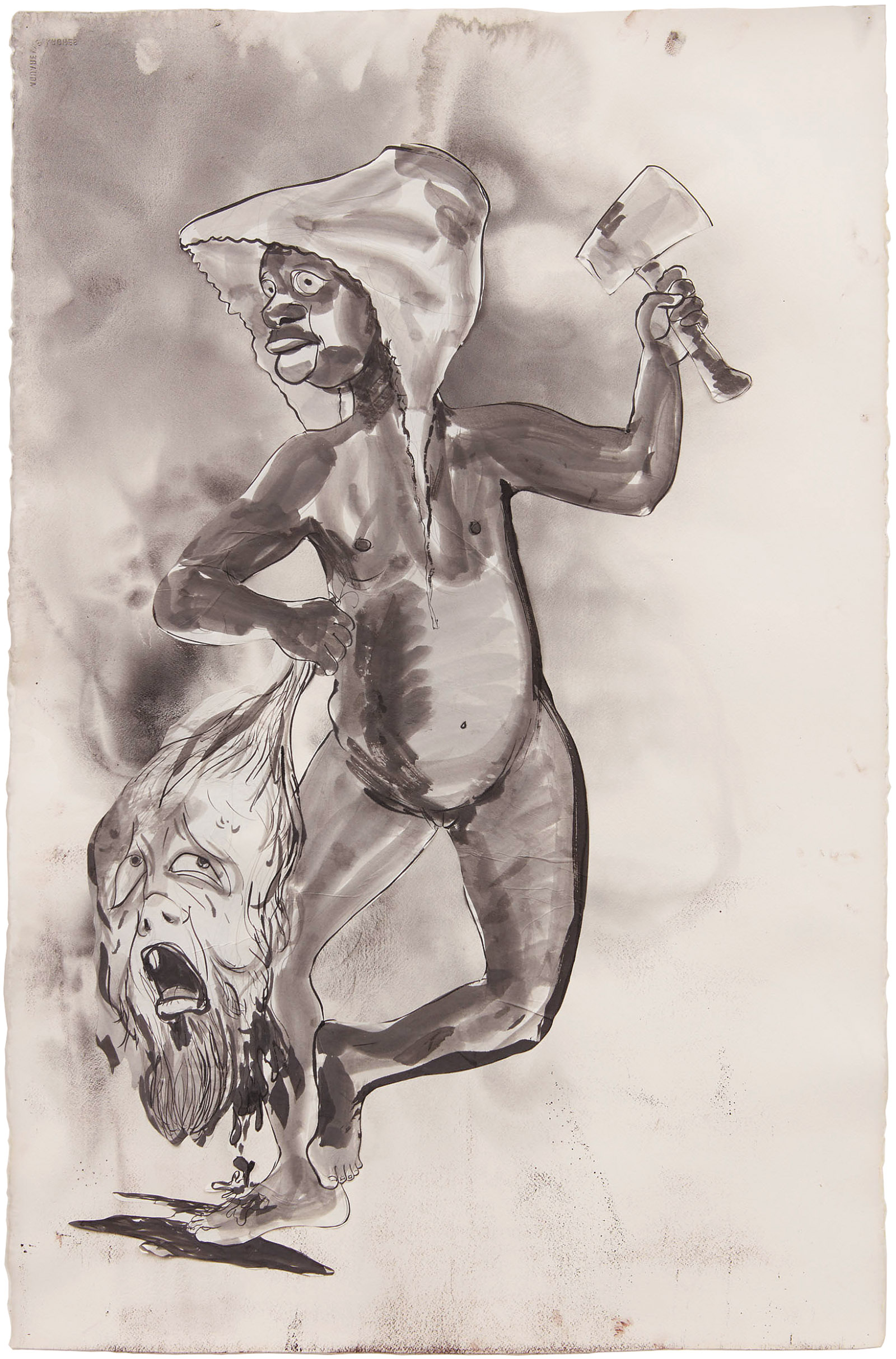

Walker’s titles set the mood, but they also set you up, and the texts of her catalogs can be intimidating in their pretended didacticism. A medium-size work done in ink and collage, Scraps, is one of the images that linger in the mind long after you have seen it. Walker shows a naked young black girl in a bonnet, with a small ax raised in her left hand. She is making off with the large head of a white man. She might even be skipping. This isn’t Judith; it’s a demented Topsy in her festival of gore. Slavery drove both the slaver and the enslaved mad and itself was a form of madness. It’s the look Walker puts in the little girl’s visible eye. Racial history has broken free and is running amuck. But even this work has a strange elegance. She is not an exorcist, is not trying to be therapeutic. It is the way she fills up her spaces. With Walker you feel that everything is placed with delicacy and each gesture conveys so much.

I sometimes find myself remembering the great Sphinx of white sugar that Kara Walker built three years ago in an unused, emptied-out sugar refinery in Brooklyn along the East River: A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant. The refinery was enormous, the walls streaked with sugar. In the distance, the large figure of a Mammy rested in her Egyptian pose, a bandana on her head. The small basket-carrying boys made of dark red molasses who attended her were melting in the summer heat, folding over onto the floor. The large and roving crowd was quiet, as if under a spell. People took photographs of themselves standing between her creamy-looking arms.

The Harlem Renaissance journalist J.A. Rogers said that before the Sphinx lost her face she was a black woman. He cited the writings of an eighteenth-century traveler, the Comte de Volney, as his source. Everyone thought he was crazy. Kara Walker didn’t need either source, and as you walked around the rear of the Mammy figure, maybe expecting a big fig leaf or a blank, neutral area, there were the folds of a huge vulva. It was beautiful that Walker had not lost her nerve.

This Issue

November 9, 2017

What Are We Doing Here?

Small-Town Noir

-

*

See the catalog, published in 2013, of the exhibition of 2011, Dust Jackets for the Niggerati—and the Supporting Dissertations, Drawings, submitted ruefully by Dr. Kara E. Walker. ↩