The Belgian city of Liège was a fitting location to inaugurate the riveting exhibition “21 rue La Boétie.” At the sale in Lucerne in June 1939 of 125 works of “degenerate” art deaccessioned from German museums, Liège acquired nine outstanding paintings, including works by Gauguin, Ensor, Marc, and Picasso, for the municipal collections. Paul Rosenberg—the preeminent Parisian dealer of nineteenth- and twentieth-century French painting who was the subject of the exhibition—was outspoken in his opposition to collectors or institutions making purchases that brought revenue to the Nazis’ coffers.

At one level, this ambitious project devoted to the life and times of Rosenberg (1881–1959) continued a trend of recent exhibitions on art dealers of the early modern era, such as Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard. Yet it also covered terrain—memorably brought to light in Stephanie Barron’s “‘Degenerate Art’: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany,” shown in Los Angeles and Chicago in 1991, and more recently in the Neue Galerie’s “‘Degenerate Art’: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937” (2014)—that is far less often treated in art exhibitions.

This Franco-Belgian collaboration was based on the elegiac memoir 21 rue La Boétie by Anne Sinclair, a granddaughter of Rosenberg’s, in which she recounts her family’s history and above all her grandfather’s escape from Paris to New York in the summer of 1940.1 Sinclair, from 1984 to 1997 the popular host of the French television show 7/7—a Gallic equivalent of CBS’s 60 Minutes—enjoyed a brief (and unwelcome) notoriety in New York in May 2011 when her husband, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the former head of the IMF, was accused of assaulting a maid in a midtown Manhattan hotel. (Sinclair and Strauss-Kahn divorced in March 2013.)

Paul Rosenberg was one of five children and the third son born to Alexandre Rosenberg (1845–1913), from Bratislava, and Mathilde Jellinek (1857–1923), from Rechnitz, then part of Hungary. They were married in Vienna in October 1878 and made their way to Paris shortly thereafter. A successful grain merchant, Alexandre Rosenberg changed professions after five of his steamships arrived from Argentina with ruined cargo. He turned to art dealing in the late 1880s, establishing a gallery at 38, avenue de l’Opéra, and engaging two of his sons, the eldest, Léonce (1879–1947), and Paul, as apprentices in the family business.

Although his father dealt primarily in old masters and modern salon painting, Paul remembered being taken by him to an exhibition of Van Gogh’s paintings in April 1892, and shrinking in horror at the sight of Bedroom in Arles. (In the 1920s, two of the three versions of this painting—those now in the Art Institute of Chicago and the Musée d’Orsay—would pass through his hands.) “After my father had calmed me down,” Rosenberg recalled, “he said, ‘I do not know this artist, not even his name, since the canvas isn’t signed, but I am going to own it. I would like to own a work by this artist.’”2

After Alexandre’s retirement in 1903, Paul and Léonce assumed the running of the gallery, mounting fairly modest exhibitions of modern art. The Impressionist Albert Lebourg was a house favorite; Odilon Redon was offered an exhibition for the winter of 1908, but declined.3 The brothers parted company in 1910, and in January 1914 Paul opened glamorous new quarters at 21, rue La Boétie with an exhibition of forty-six paintings by Toulouse-Lautrec. The painter and critic Jacques-Émile Blanche, visiting Rosenberg’s premises three years later, wrote admiringly of this “marble-fronted Ritz palace, with its staircase of onyx and its vast rooms of watered silk, illuminated by clusters of light bulbs like grapes on the vine.”4 Léonce—who had acquired his first Picasso in 1906—opened the Galerie Haute Époque on the nearby rue de La Baume in 1910 and was an early and passionate advocate of Cubism, replacing the exiled Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler as Picasso’s dealer in 1915, supporting Gris and Léger, Rivera and Severini, and putting Braque under contract in November 1916.5

On July 7, 1914, three weeks before the outbreak of World War I, Paul married Marguérite (“Margot”) Ida Loévi (1893–1968), daughter of a Parisian wine merchant. Two children were born to the couple some years later: a daughter, Micheline Nanette—Sinclair’s mother—in June 1917, and Alexandre, whose birth was witnessed by Picasso, in March 1921. This prosperous family was part of a circle of mondain Jewish art dealers specializing in Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and modern painting, all established in Paris’s eighth arrondissement. Jos Hessel and Georges Wildenstein had galleries on the rue La Boétie; Josse and Gaston Bernheim-Jeune moved their premises to the nearby avenue Matignon in 1925. In 1923 Margot Rosenberg began an affair with Wildenstein that continued for nine years. Paul’s discovery of it in 1932—and his refusal to contemplate divorce—brought an abrupt and irreversible end to the association with his former business partner.6

Advertisement

Although his elder brother Léonce had assiduously cultivated avant-garde painters in the interwar years, it was Paul Rosenberg who in the 1920s succeeded in placing Picasso, Braque, and Léger under contract, and who finally convinced Matisse to sign with him in 1936. Rosenberg’s earliest transactions with Picasso, as part of a dealer’s consortium, dated to July 1917. In January 1918, he responded to Picasso’s chronic need for money by buying one of his Renoirs—a painting of a girl reading—for 8,500 francs. Only after the summer of 1918, when their families were holidaying in Biarritz, did the two men become friends. For a while they were “Pic” and “Rosi,” with Rosenberg in October arranging for Picasso to rent the fourth floor of the apartment next door at 23 bis, rue La Boétie. Painter and dealer could now speak to each other from their respective balconies. “It’s very convenient,” the Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant recalled Picasso telling him. “When I need cash, I open my kitchen window, whistle ‘Paul,’ and he comes running over with bags of money.”7

In the summer of 1918, Paul commissioned Picasso to paint a portrait of Margot and two-year-old Micheline in an Ingresque style reminiscent of Picasso’s recent portrait of his own wife, Olga in an Armchair (now in the Musée Picasso). Margot had to endure “the martyrdom of posing” on a Sunday afternoon.8 She is shown in bourgeois comfort in a high-backed tapestry-covered armchair, similar to the one in which Olga is seated in her husband’s portrait of her, painted earlier in the year. Following this commission, Picasso made an elegant and respectful portrait drawing of Rosenberg himself, again indebted to Ingres, in which the dealer—immaculate in spats and with the inevitable cigarette in his right hand—looks older than his thirty-seven years. It is a sympathetic portrayal but registers something of the steeliness alluded to by the dealer René Gimpel—a classmate of Léonce’s and Paul’s—in his journal a year later: “He’s no fool, with a face like a short-muzzled fox, and cheekbones that are prominent and grained.”9

Before the crash of 1929, Picasso received steadily increasing payments from Rosenberg: 50,000 francs in 1918; 121,000 francs in 1921; 244,000 francs in 1923; and an astonishing 457,000 francs in 1925. (There were no major purchases between 1930 and 1934.)10 The gallery at 21, rue La Boétie mounted its first Picasso show—167 drawings and watercolors—in October 1919; thirty-three oil paintings were included among the thirty-nine works shown there in May 1921; and in November 1923, Rosenberg organized a small exhibition of sixteen paintings for Wildenstein’s gallery in New York, which traveled to the Arts Club of Chicago the following month. “Your exhibition is a great success,” he informed Picasso on November 26. “And, like all successes, we have sold absolutely nothing!”

Rosenberg was less sanguine after a dinner given for him in early December by the New York lawyer and collector John Quinn. As he left his host’s apartment on Central Park West, he confided to the other guests in the elevator that he was “disgusted with America…and was not coming back again.”11 Yet Rosenberg’s determination to keep Picasso’s prices high reaped benefits early on. In April 1924, Gimpel noted with astonishment that his fellow dealer was offering twelve Picassos that had failed to find buyers in New York for no less than 100,000 francs each, and that some were indeed selling.

These prices notwithstanding, it was Rosenberg’s commitment to the aging or recently deceased Impressionists, his exceptional connoisseurship in nineteenth-century French painting, and the growing American demand for such work that secured his gallery’s fortunes and helped maintain Matisse’s and Picasso’s attachment. In August 1918 Rosenberg acquired Monet’s La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume) (1876; now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston) for 150,000 francs. He immediately sought confirmation of its authenticity from the artist, to whom he sent a black-and-white photograph. Monet replied from Giverny that it was years since he had laid eyes on the painting, “But I greatly fear that in seeing it again, I share your enthusiasm.”12 Doubling his price, Rosenberg now asked 300,000 francs for La Japonaise and sold it to Philip Lehmann from New York in February 1920.

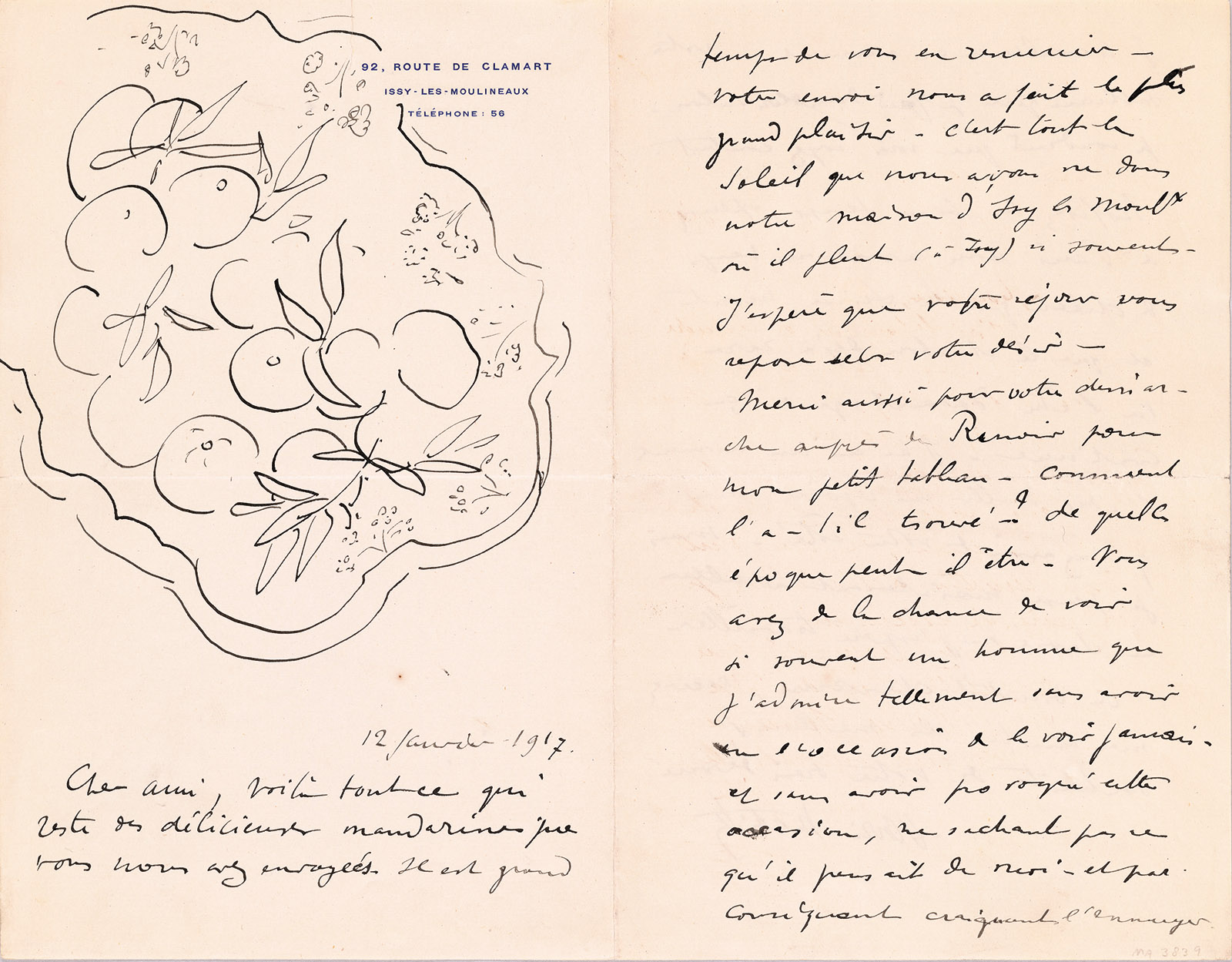

Rosenberg had established a business relationship with Renoir by 1911 but had grown close to him only in the final years of World War I, sending champagne and cigarettes as Christmas presents in December 1916.13 He acted as a sort of unofficial emissary for Matisse and Picasso, both of whom venerated the aging master but had yet to meet him. On December 27, 1916, Rosenberg brought one of Matisse’s “little Renoirs” to the artist for authentication. (“What did Renoir think of it? What period does he think it’s from?”) In thanks—and also for Rosenberg’s gift of “delicious mandarins”—Matisse wrote on January 12, 1917, “You are most lucky to see so often a man I admire so much but whom I have never had the opportunity to meet. I would never have proposed such a thing myself, not knowing what he thinks of me, and not wanting to bother him.”14 (See illustration on page 24.) It would be another twelve months before Matisse summoned the courage to make a visit to Les Collettes—the first of many during the last two years of Renoir’s life.

Advertisement

Rosenberg also hoped to orchestrate the first meeting between Renoir and Picasso. On July 24, 1919, the seventy-eight-year-old Renoir had informed the dealer that, as was his custom, he was planning to spend the first two weeks of August in Paris. On July 29, Rosenberg wrote to Picasso at the Savoy Hotel in London—where he was staying courtesy of Diaghilev, for whom he was producing the drop sets, curtains, and costumes for the ballet Le Tricorne—that Renoir was about to come to Paris and “desires very much to see you. He has been amazed by certain of your things, and even more shocked by others.” Picasso conveyed this news rather differently to Clive Bell, bragging that “this vieillard” (that is, Renoir) had just sent him a letter in which he said that his main reason for coming to Paris was to see him and his work. The two artists never met, but later in the year Rosenberg sold Picasso Renoir’s Bather Seated in a Landscape (Eurydice) (circa 1900; Musée Picasso, Paris). For decades it would hang, crooked but in a place of honor, above a fireplace in Picasso’s apartment on the rue La Boétie.

During the economic recovery of the mid-1930s, Rosenberg continued to exhibit both nineteenth-century and Impressionist masters alongside the work of the contemporary Parisian painters in his stable. In 1936, for example, his gallery mounted no fewer than seven shows: recent work by Braque in January, by Picasso in March, by Matisse in May, and a group show of works by twelve contemporary painters in November. These alternated with a Seurat exhibition in February, Monet’s paintings from 1891–1919 in April, and in June and July a survey of “le Grand Siècle” (the nineteenth, not the seventeenth) for the benefit of the Société des Amis du Louvre.

In the same year appeared Lionello Venturi’s two-volume catalogue raisonné of Cézanne, financed by Rosenberg, who also underwrote the same author’s catalogue raisonné of Pissarro, published in 1939. Rosenberg venerated Cézanne: “The master of masters, the greatest of martyrs alongside Michelangelo,” he told Matisse on December 2, 1939. The German dealer Walter Feilchenfeldt considered Rosenberg’s connoisseurship of Cézanne’s work to be more discriminating than that of the art historian Venturi.

Thanks to exceptional loans from the Centre Pompidou, MoMA, the Bürhle collection in Zurich, and the dealer David Nahmad, the exhibition “21 rue La Boétie” assembled a group of notable Impressionist paintings and outstanding works by Picasso, Braque, and Léger. (Matisse was underrepresented.) Rosenberg’s activities and fortunes as a dealer in Paris and New York were depicted chronologically in thirteen sections, with photographs of his gallery’s interiors before and after the Nazi occupation, reproductions of its ephemeral exhibition catalogs, and of the annotated and illustrated index cards that formed the core of Rosenberg’s meticulously maintained records. The timeline of the years leading to World War II and the seizure of Jewish property made for absorbing, if harrowing, reading.

Through the deft use of clips from two documentary films of the late 1930s, the exhibition introduced the dramatic shift in Rosenberg’s life and career during World War II that is the focus of Sinclair’s memoir. The amateur filmmaker Hans Feierabend’s footage of the Day of German Art showed the Nazis’ celebrations of two thousand years of German art in Munich on July 16, 1939. Feierabend had access to Hitler and the German leadership, and the kitsch sensibility of his panoramas, shot in Kodachrome, still has the power to shock. This was paired with a more familiar documentary film, Julien Bryan’s black-and-white record of the Nazi-sponsored exhibition of degenerate art, shown between 1937 and 1941 in Munich and twelve other cities (and seen by over two million visitors). The film was shown in American cinemas on January 20, 1938, as part of the March of Time newsreel “Inside Nazi Germany.”

Assimilated into liberal-leaning haute bourgeois society—“Jews of discretion,” to use André Aciman’s phrase—Rosenberg was nonetheless aware of the danger in which his prominence as a wealthy and successful Jewish art dealer placed him and his family. From the mid-1930s he had systematically begun to send portions of his stock abroad: to the Rosenberg gallery in Bruton Street, London, and to traveling exhibitions in New York, Chicago, Australia, and South America. On September 3, 1939, the day that war was declared, he stored a number of paintings in a bank vault in Tours under the name of his chauffeur, Louis Le Gall, and closed his gallery in Paris.15 Early in February 1940, Paul and his family moved to Floirac La Souys, a town of seven thousand inhabitants three miles east of Bordeaux, where they rented a neo-Gothic château, Le Castel, built in the 1820s. He placed 162 paintings in a bank vault in nearby Libourne. (It would be looted on September 5, 1941.) Paul remained active until the spring of 1940, traveling in April to visit Matisse in Nice and returning with some of his recent paintings, which he hung in the salon at Le Castel. “After contemplating them again,” he wrote to the painter, “I went to say hello to my family. I was very tired after an eighteen-hour journey, the sight of your canvases revived me.”

Rosenberg decided to leave France two days after Hitler’s army entered Paris on June 14, 1940, and three weeks before the Nazis’ systematic confiscation of Jewish art collections in France began. He and his extended family were able to obtain twenty-one refugee visas to Portugal, issued in Bordeaux on June 18. It took three days for their convoy of cars to travel the 125 miles across Spain to Sintra, on the outskirts of Lisbon, where he, his wife, and their daughter would board the SS Exeter for New York. Before arriving in Portugal, the Rosenbergs had said good-bye to nineteen-year-old Alexandre, who traveled by ship from Bordeaux to London and eventually joined the Free French forces in North Africa.16

In Paris, Rosenberg’s stock was impounded immediately after Nazi legislation was enacted on June 30, 1940, for the confiscation of Jewish collections “for safekeeping.” On September 15, 1940, five days before the SS Exeter disembarked in New York, the house in Floirac was ransacked after Rosenberg had been denounced by some of his Parisian colleagues. In May 1941 Rosenberg’s gallery in Paris became the headquarters of the newly founded Institut d’étude des Questions juives (IEQJ), a Nazi propaganda agency financed jointly by the German embassy and the Gestapo, initially under the directorship of the virulent anti-Semite Paul Sézille. The institute would be responsible for organizing the exhibition “Le Juif et la France,” shown at the Palais Berlitz between September 1941 and January 1942, and attended by 200,000 visitors.

Residing (and conducting business) from September 1940 in the Madison Hotel at 15 East 58th Street, Rosenberg opened a gallery one block south at 16 East 57th Street in November 1941. In the spring of 1942, he was shaken to learn that he had been stripped of his French citizenship. His outraged, but futile, telegram to Vichy’s Ministry of Justice of March 26 testifies to his utter distress: “Have just learned of the loss of my citizenship…. Protest energetically and register immediate objection. Letter follows.” While he was determined to seek recovery of the four hundred works stolen from him by the Nazis—as early as July 1942 he wrote (with great naiveté) to his fellow dealer Feilchenfeldt that “all of this will be resolved at the end of the war and I hope to find them all again”17—he never returned to live and work in Paris.

Supported by the impeccable recordkeeping of the Rosenberg gallery, Paul’s older brother Edmond would serve as the family’s Parisian representative with the French authorities. In April 1945 Paul admitted that he felt confident of recovering the pillaged paintings, but this was “as nothing when you look at the horrors that the Nazis inflicted on human beings of all races, creeds, and colors.” The process of restitution began in earnest even before the war ended. For example, on November 4, 1944, Rosenberg sent a radiogram to Matisse in Nice, asking him if he had photographs of the last works that he had purchased from him, “since all of them have been taken by the Boches and resold.” Matisse replied, “Photographs at your disposal. Am in good health and working,” and on December 13 he sent images of the seven paintings that Rosenberg had acquired in 1940.18

In September 1945, Rosenberg made a special effort to recover the thirty-seven stolen paintings identified in Swiss collections, traveling to Zurich to confront such prominent collectors as Emil Georg Bührle, who had argued that, since Rosenberg had been stripped of his nationality by the Vichy government, he no longer had title to these works. When the case finally came to trial on June 3, 1948, the Swiss Federal Tribunal in Lucerne—“to its eternal credit”—found in Rosenberg’s favor and ordered that all the paintings be restored to him.19 During the postwar years, Rosenberg recovered more than three hundred works, thirty-six of which he donated to France’s Musée National d’Art Moderne. His daughter-in-law and grandchildren have continued to monitor the art market and sue for the return of stolen works. As recently as May 2015, Matisse’s Seated Woman (1921), from Cornelis Gurlitt’s collection, was returned to the family.

While Rosenberg already had enjoyed a fairly long association with MoMA—having lent as many as thirty works by Picasso in 1939—in New York he was now eager to do business with the Frick Collection, which had opened in December 1935. In March 1939, before leaving Paris, Rosenberg had offered the Frick two paintings by Cézanne, which were both turned down.20 In March 1941, he was encouraged to send on approval Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889)—entitled “La Nuit” and priced at $50,000—and Degas’s Portrait of Giovanna and Giulia Bellelli (1865–1866), for which he was asking $45,000. The Frick’s director, Frederick Mortimer Clapp, was enthusiastic in his support of both paintings, explaining to trustees Junius Spencer Morgan and Helen Clay Frick (the founder’s daughter) that in Van Gogh’s landscape of fields with stars, “his intensity of vision and sense of lyric harmony of the universe as a throbbing whole is expressed with moving sympathy.”21 Both paintings were returned; Starry Night was acquired by MoMA shortly thereafter.22 In the end, the Frick acquired none of the significant paintings—by Ingres, Van Gogh, and Cézanne, among others—that Rosenberg offered it over the next half-dozen years.

“Le marchand, voilà l’ennemi”: Picasso’s boutade of 1918 had Léonce Rosenberg in its sights, but its tone has infiltrated some of the best writing about his far more successful brother. Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson, has stressed Paul Rosenberg’s “persistent dealerism”: “Rosenberg was an enormously successful dealer—totally focused on the art market, immensely hardworking, rapacious, and deeply committed to his artists, so long as their work sold.” Paul’s irreverent interview with the Greek critic E. Tériade, published in 1927—“I find a painting beautiful when it sells, and I discover a painter once he is already well-known”—did little justice to his discrimination, connoisseurship, and conviction.23

Admittedly, it is hard to get a sense of this driven, highly professional—and extremely knowledgeable—art dealer. Tériade described Rosenberg as “a man dressed all in black, at once nervous, ascetic, and passionate about business.” Anne Sinclair, who was eleven years old when he died, remembered her grandfather as “thin, distant-looking…elegant, always elegant…an anxious and shy man who relaxed more easily in his letters to his beloved daughter than in his conversations with her.” In a confessional family document, written in 1942, Rosenberg described himself as “very self-contained,” but still haunted by his wife’s infidelity: “The more I worked, the more money I made, the more I became a slave to business, a slave in chains…. Life became torture for me.” And Richardson’s harsh appraisal of Rosenberg as a “steely operator who cared far more for the business of art than for art itself” is nuanced by a surprisingly generous remark made by Matisse in December 1934. Recounting a recent visit to the gallery at 21, rue La Boétie, Matisse wrote to his son, Pierre:

I saw Rosenberg, who galvanized me, told me I was wrong to allow myself to be forgotten…. He showed me many beautiful paintings, van Gogh, Corot, Renoir, all new on the market. He told me how painting was everything for him, that it was the place where he lived.24

This Issue

November 23, 2017

The Pity of It All

Poems from the Abyss

Virgil Revisited

-

1

Published in English as My Grandfather’s Gallery: A Family Memoir of Art and War (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014). ↩

-

2

Paul Rosenberg and Company: From France to America: exhibition of documents selected from the Paul Rosenberg Archives, presented at the Museum of Modern Art, by the MoMA Museum Archives in collaboration with Mrs. Elaine Rosenberg, New York, January 27–April 5, 2010 (Paul Rosenberg & Co., 2012). ↩

-

3

Lebourg showed at the Galerie Rosenberg in November 1903 and April 1906. For Redon’s letters to Paul Rosenberg, dated August 12 and September 22, 1908, see Gift of Mrs. Alexandre P. Rosenberg (2013), MA 9076, The Morgan Library and Museum. ↩

-

4

Jacques-Émile Blanche, Cahiers d’un artiste, Décembre 1916–Juin 1917 (Paris: Émile-Paul Frères, 1919). ↩

-

5

For a succinct introduction, see Michael C. Fitzgerald, Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-century Art (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), pp. 56–67. ↩

-

6

John Richardson, A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years: 1917–1932, with the collaboration of Marilyn McCully (Knopf, 2007), pp. 373–374; Sinclair pp. 145–149. ↩

-

7

Amédée Ozenfant, Mémoires, 1886–1962 (Seghers, 1968), p. 146; the reminiscence dates from the mid-1920s. Richardson, p. 297, dates the decline of Picasso and Rosenberg’s friendship and the establishment of a purely business relationship between them to the autumn of 1925 and quotes from Rosenberg’s letter to Picasso of November 1925, where he writes that he is “seriously worried” that he has not heard from him. ↩

-

8

Fitzgerald, A Life of Picasso (1995) pp. 84–86; Richardson, pp. 90–91; 21 Rue La Boétie, p. 175. An undated letter from Picasso to Rosenberg, written on “vendredi soir,” reads, “Impossible de commencer demain le portrait…nous prendrons rendez vous pour après demain, si Madame R est prete au martire de la pose.” Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alexandre P. Rosenberg (1980), MA 3500, The Morgan Library and Museum. ↩

-

9

René Gimpel, Diary of an Art Dealer (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966), p. 121. ↩

-

10

Fitzgerald, Making Modernism, pp. 90, 110–111, 153, 295. As the author notes, records of Picasso’s sales to Rosenberg between 1927 and 1939 have not survived. ↩

-

11

John Quinn to Henri Pierre Roché, December 6, 1923, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. ↩

-

12

“Il y a bien des années que je n’ai vu ce tableau, mais j’ai grand peur que le revoyant, je partage votre enthousiasme”—Monet to Paul Rosenberg, August 6, 1918, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alexandre P. Rosenberg (1980), MA 3500, The Morgan Library and Museum. ↩

-

13

For the cigarettes, see Albert André to Paul Rosenberg, January 5, 1917, gift of Mrs. Alexandre P. Rosenberg (2013), MA 9076.1, The Morgan Library and Museum. The vintner’s receipt of December 3, 1916, for Rosenberg’s gift of a case of “12 Belles Fines Champagne 1898,” is in The Paul Rosenberg Archives, I C 21 B, 430/431, MoMA Museum Archives. ↩

-

14

Matisse to Paul Rosenberg, January 12, 1917, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alexandre P. Rosenberg (1980), MA 3500, The Morgan Library and Museum. The original reads: “Merci aussi pour votre demarche auprès de Renoir pour mon petit tableau—comment l’a-t-il trouvé-et de quelle époque peut-il être? Vous avez de la chance de voir si souvent un homme que j’admire tellement sans avoir eu l’occasion de le voir jamais et sans avoir proposé cette occasion, ne sachant pas ce qu’il pensait de moi—et par conséquent craignant l’ennuyer.” ↩

-

15

Sinclair notes, “These would be the first paintings recovered after the war because neither the Nazis nor the French authorities were aware of their existence (p. 43).” ↩

-

16

On August 27, 1944, Alexandre led a small group of volunteers who had been alerted to the departure of a train containing one final convoy of looted art that was about to leave Paris for Germany. They captured train No. 40044 at Aulnay-sous-Bois, in the suburbs of Paris, and recovered some 148 crates of paintings and drawings, including those belonging to his father. See Lynn H. Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War, (Knopf, 1994), p. 292. This incident was the subject of John Frankenheimer’s 1964 film The Train, starring Burt Lancaster, Paul Scofield, and Jeanne Moreau, clips of which were shown at the exhibition at the Musée Maillol. ↩

-

17

Letter cited by Lucas Gloor in “Emil Bührle and Paul Rosenberg: A Business Relationship at the Dawn of the Post-war Era,” in exhibition catalog, p. 134. ↩

-

18

Matisse to Paul Rosenberg, 1939–1949, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alexandre P. Rosenberg (1980), MA 3500.e, The Morgan Library and Museum. ↩

-

19

Lynn Nicholas, who documented these proceedings in The Rape of Europa (2007, p. 420), noted that “the defense was far worse than the crime. Not one of the defendants denied having knowingly bought stolen goods; instead they attempted to discredit Rosenberg’s title to the paintings on the grounds that the confiscations had been carried out with the consent of the legal government of France at the time.” ↩

-

20

Frederick Mortimer Clapp to Paul Rosenberg, January 18, 1940, Frick Archives, Frick Collection. ↩

-

21

Clapp to Junius Spencer Morgan, March 13, 1941, Frick Archives, Frick Collection. ↩

-

22

Art in Our Time: A Chronicle of the Museum of Modern Art, edited by Harriet S. Bee and Michelle Elligott (Museum of Modern Art, 2004), pp. 73, 248. ↩

-

23

E. Tériade, “Nos enquêtes: Entretien avec Paul Rosenberg,” Feuilles Volantes Supplément a la Revue Cahiers d’Art, Vol. 9 (1927), pp. 1–2. ↩

-

24

Sinclair, p. 104; in French, “Il m’a dit combien la peinture était pour lui, qu’il vivait dedans.” ↩