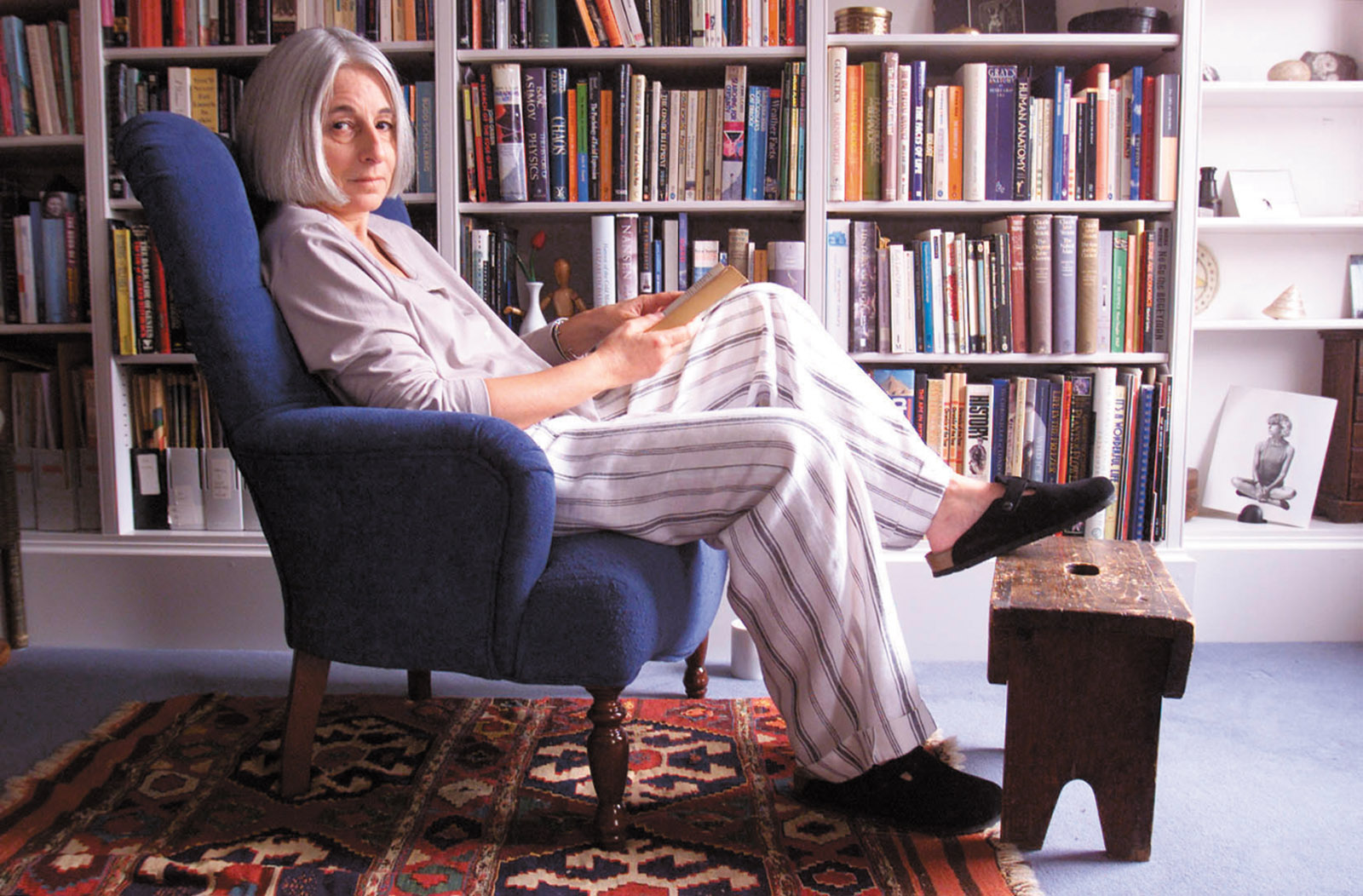

Jenny Diski covered nearly every conceivable topic in her essays for the London Review of Books: shoes, Stanley Milgram, the women’s movement, Karl Marx. But the essays are always as much about herself as the subject at hand. “I start with me, and often enough end with me,” she once wrote. “I’ve never been apologetic about that, or had a sense that my writing is ‘confessional.’ What else am I going to write about but how I know and don’t know the world?”

Sometimes she does this head-on, as when she discusses Roman Polanski’s rape of a thirteen-year-old girl along with her own at age fourteen. Or in a review of a book on asylums, which she is barely able to write because, having spent much of her childhood in one herself, she begins to get competitive with all the inmates described:

As I read, I saw myself flitting through the pages of Taylor’s account like a precursor-ghost, or perhaps more a tetchy sprite, engaged in a debate with her text, ticking off the similarities between her experience and mine and weighing up the differences…. “I should have been MUCH madder than I was. I haven’t been NEARLY mad enough.”

But even when she doesn’t talk directly about herself or her own experience, there’s an intelligence and humor that immediately identify the writing as hers. She writes in an essay about Germaine Greer:

The problem with being a dedicated social trouble-maker who has not self-destructed is that, as the decades roll by, the society you wish to irritate gets used to you and even begins to regard you with a certain affection. Eventually, you become a beloved puppy that is always forgiven for soiling the carpet. No matter what taboos you kick out at, people just smile and shake their head.

Her writing is sharp, sometimes mean, sometimes seems to roam. It moves from observation to joke to fact to analysis. In this, one experiences the uncommon, pleasurable feeling of watching someone think.

This combination is not popular with everyone—I remember giving a friend a copy of Stranger on a Train, Diski’s book about traveling across America and her own time spent in and out of mental hospitals. It was promptly returned. “An American travelogue? This woman won’t stop talking about her feelings.” But the clarity of her mind at work accounts for the fact that readers who like Diski really like her. She is the rare writer who records her thoughts without going to great lengths to justify them. Reading Diski, one has the satisfying sense that she wrote exactly what she wanted to write.

Diski died last year, after a treatment for lung cancer that she detailed in the London Review of Books, along with a series of pieces about her adolescence living with Doris Lessing. Kicked out of her house after being expelled from school and getting fired from various menial jobs, she had a breakdown and ended up in an asylum, where she spent a number of months before being taken in by the older writer. It’s a story that she told in many of her books, and that comes up in her writing as a central experience through which she viewed the present. One sees traces of the story in many of her nonfiction books, whether the subject is traveling to New Zealand or the Sixties, as well as in her ten varied and inventive novels, many of which she wrote early in her career.

Take her memoir Skating to Antarctica, a book describing a trip to the southern continent and her attempt to learn more about her mother, who cracked up and abdicated her duties when she was young. (Asked what the book was about, Diski would respond, “Icebergs, mothers. That sort of thing”—an answer both enigmatic and accurate.) The book is clearly not a work of travel writing. Here is Diski on the boat:

Stefan dutifully pointed out some of the bird species which form the real animal life of the archipelago. Great grebes, upland geese, kelp geese, sea snipe…. Me, I was checking my watch to see how long it was until I got to my cabin, when some really interesting bird flapped by, so I missed it.

You can imagine the editor screaming: We sent you eight thousand miles away for this?

Yet the no-bullshit tone is immediately appealing. If they were related with any sentimentality, the events Diski describes would hardly be believable. Her mother’s grotesque, hysterical attack of madness: “She was rolling frantically from side to side in the bed, the covers in turmoil…. Spittle dribbled from the corners of her mouth.” Diski’s own ability to spend decades without seeing her mother and feel no curiosity about her:

Advertisement

From time to time, in the cause of self-knowledge, I would excavate, try to dig down below my contentment with the situation, but beyond the strong wish for the situation…to continue, I could find no underlying seismic fault waiting to open up.

The months she spent as an adolescent in mental hospitals, “places of safety, blank places of white sheets and nothing happening.”

Plenty of writers have made careers by milking messy childhoods for pity or laughs. Entire bookshelves could be filled with stories of abusive teachers and terrible parents. What makes Diski’s nonfiction particularly impressive is that she doesn’t try to recount these events like a story at all. Her voice is calm and precise as we slip from descriptions of penguins standing on the shoreline (“That’s what penguins do. Stand”) to interviews with her childhood neighbors, who seem at pains to convince her that they tried to do what they could to look after her:

We don’t ask. If people tell us, we’ll listen, but we don’t probe anybody… I wasn’t aware… Had we known… She wasn’t actually a personal friend—well, at one time.

She keeps her gaze steady even when describing what others would call sexual assault: her parents chasing her around the house, trying to grab her crotch. “Looking back, it’s clear to what extent I was a conduit between them, in good times and bad, a lightning rod for their excitement and their misery.” Few writers approach their memories of being assaulted as children with this same sort of tone with which they might write about birds. But Diski makes the reader look at the assault not as something extraordinary and traumatic but as a reality of her life. It is something that happened, and therefore something that should be described.

There’s a push and pull as Diski moves from her visits to Antarctica to the facts of her childhood. She finds out all she needs to know about her mother—her desire to keep up appearances, even after the bailiffs had taken away all their furniture (mother and daughter walked barefoot so the downstairs neighbors wouldn’t know they had no carpets); moments of tenderness and happiness that Diski had not remembered; even rare instances of good mothering. She learns that her father, a charming con man who modeled himself after Errol Flynn, had also tried to commit suicide:

What sent me to bed was the thought—no, the conviction—that I was the sum of those two people, that under the pretence of an achieved balance, more or less, I hadn’t got a hope in hell of being other than what they were.

It’s not neat, nor does it try to be. Diski doesn’t present a redemption narrative or a forgiveness narrative or a trauma narrative or any rigid narrative at all. There’s no conclusion and no lesson. There are just the facts of the past and the reality of the present. Her memories of childhood never quite settle; as the book unfolds, they continue to swirl and move, one part here, another there. “Memory,” she writes,

does not have a particular location in the brain, as was once thought, but resides in discrete packets dotted all over the place. Or it doesn’t reside anywhere, except in the remembering itself, when the memory is created from the bits of experience stored around the brain. Memory is continually created, a story told and retold, using jigsaw pieces of experience.

And then we are back, in a sense, in Antarctica again:

The will to live was not strong in my family. I had my own version of it, which I had developed into a passion for oblivion…. Depression is rotten, you cannot sit through the pain if your circumstances aren’t right, if you haven’t got support, or if you have people depending on you. And even if those conditions can somehow be met, to sit through the pain carries the very real risk that you will not survive it. But given that depression happened to me, and I did have support, I found it was possible after a time to achieve a kind of joy totally disconnected from the world. I wanted to be unavailable and in that place without the pain. I still want it. It is coloured white and filled with a singing silence. It is an endless ice rink. It is antarctic.

Direct, honest, and immediate, this is among the best descriptions of depression I’ve read. Diski is able to depict a state in which every sense of observation has been shut down. And yet one can almost see the absence of feeling and Diski within it. How many people have the presence of mind to record their emotions so clearly?

Advertisement

Now Ecco has reprinted a collection of Diski’s short stories from 1995, The Vanishing Princess. It’s a sharp, funny, clever selection. But for fans of her work it may feel like a disappointment, a bunch of crumbs when what you wanted is another cake.

Some of the stories are Angela Carter–like reworkings of fairy tales with a feminist edge. In “Shit and Gold” a miller’s daughter finds herself stuck with the familiar Grimm problem: her father has told the king that she can spin straw into precious metal. “That’s how it goes in this corner of the narrative world: the prize for doing the impossible is to become the wife of a king. Nothing to be done about that.” A small man performs the necessary magic, only to come back demanding her first-born—unless the princess can guess his name. “‘Oh please,’ [she] interrupted. ‘Don’t you get tired of this nonsense? “Guess my name. Three days.” And what would you want with a baby, anyway?’” She suggests an alternative: she gets three days to make him forget his name. She takes him to bed. “Everybody has something about them which can be found attractive.” When stumbling out of the sheets, she asks him what he’s called. He’s too worn out by the sex to respond. “And so my life is just as my father had dreamed. I am a rich and powerful woman.”

In “The Old Princess” a young woman living in a castle waits for her story to begin. Yet “in spite of all the books telling her about princesses in towers and other waiting areas and their eventual discovery, she was a princess to whom nothing was going to happen.” The woman in “Bath Time” searches for the perfect solitude of a day in the tub. “Easy, some might think, but not so easy, actually. It required the right bathroom…. It meant a day when there were no interruptions: no phone calls, no doorbells ringing, no appointments, guaranteed solitude.” Divorced and finally alone, she finds a derelict apartment and spends all her money redoing the bathroom. She looks forward to spending Christmas Day happy and soaking:

You only had to know what it was you really wanted, she told herself, wrapped in her duvet in the freezing desolate room, with the smile of a cat savouring the prospect of tomorrow’s bowl of cream.

There’s much to admire in this book—the energy of the prose, the playfulness with which Diski approaches her stories. In just under two hundred pages, she tries her hand at fairy tales, erotica, and scenes of domestic life. Such inventiveness is typical of Diski’s fiction. Her novels are incredibly varied in their form. Her first novel, Nothing Natural, shocked British audiences when it was published in 1986 because of the coldness with which it recounted a sadomasochistic affair between Rachel, a social worker, and Joshua, a mysterious, violent man. (“Feminist principles or not, it turns me on,” Rachel tells a friend.) Like Mother, another early novel, is told from the perspective of an anencephalic baby who narrates from the womb. In Only Human, a grumpy Old Testament God fights with Sarah over his love of Abraham. (Looking down on earth, God comments, “How touching. What sensitivity. What development. What drivel.”) But however daring and original, the novels lack the immediacy of Diski’s nonfiction.

As a result, the stories in The Vanishing Princess may be something of a letdown. “The first thing that happened was that she got the sack again,” thinks the teenage Hannah in “Strictempo.” Here again we have a tale of Diski’s life, “a story told and retold”:

It wasn’t anything she’d done especially, more a matter of attitude and facial expression…. Not looking as if she minded about anything required an internal organization of her facial muscles to keep everything light and steady, but the external manifestation of this internal effort tended to bring the word “belligerent” to the furious lips of those who scanned the language to explain the anger Hannah engendered in them.

Instead of working in the shop, Hannah ends up in an asylum, where as “the baby of the Bin” she passes the time dancing with the other inmates.

But presented in fiction, the episode seems a little sterile. Compare it to the way Diski would later write about the same events in her nonfiction work. She writes in the memoir In Gratitude:

It was the look I could feel from inside my face, peering through the eyes, as if it were a mask which on the outside raised a barrier of contempt, a visible defense against everything the world could do to me. I can’t do it now. It’s a look that vanishes with maturity, like that thing you did with your eyes when you were a child, focusing them so that everything looked minute and far away but at the same time near enough to touch.

What’s striking here is the clarity of Diski’s language, the precision with which she captures the anger. But even more telling is the way she acknowledges that it can’t be fully recreated. She’s not trying to reconstruct her teenage self but to record, with all the distance between then and now, the recollection of it that exists. The effect reads less like a memoir and more like the experience of memory itself.

There are no moments like this in The Vanishing Princess. Reading it, one can see Diski’s later words hovering around the edges. It’s easier to deal with stories that have a beginning and a middle and an end. But minds don’t work that way. Our experience of the past is not linear. It pokes through, it prods, it shapes how we view the world no matter how distant it may feel. What makes Diski’s work so brilliant is that she was able to present her life in all its untidiness.

This Issue

December 7, 2017

Norwegian Woods

Ku Klux Klambakes

Outing the Inside