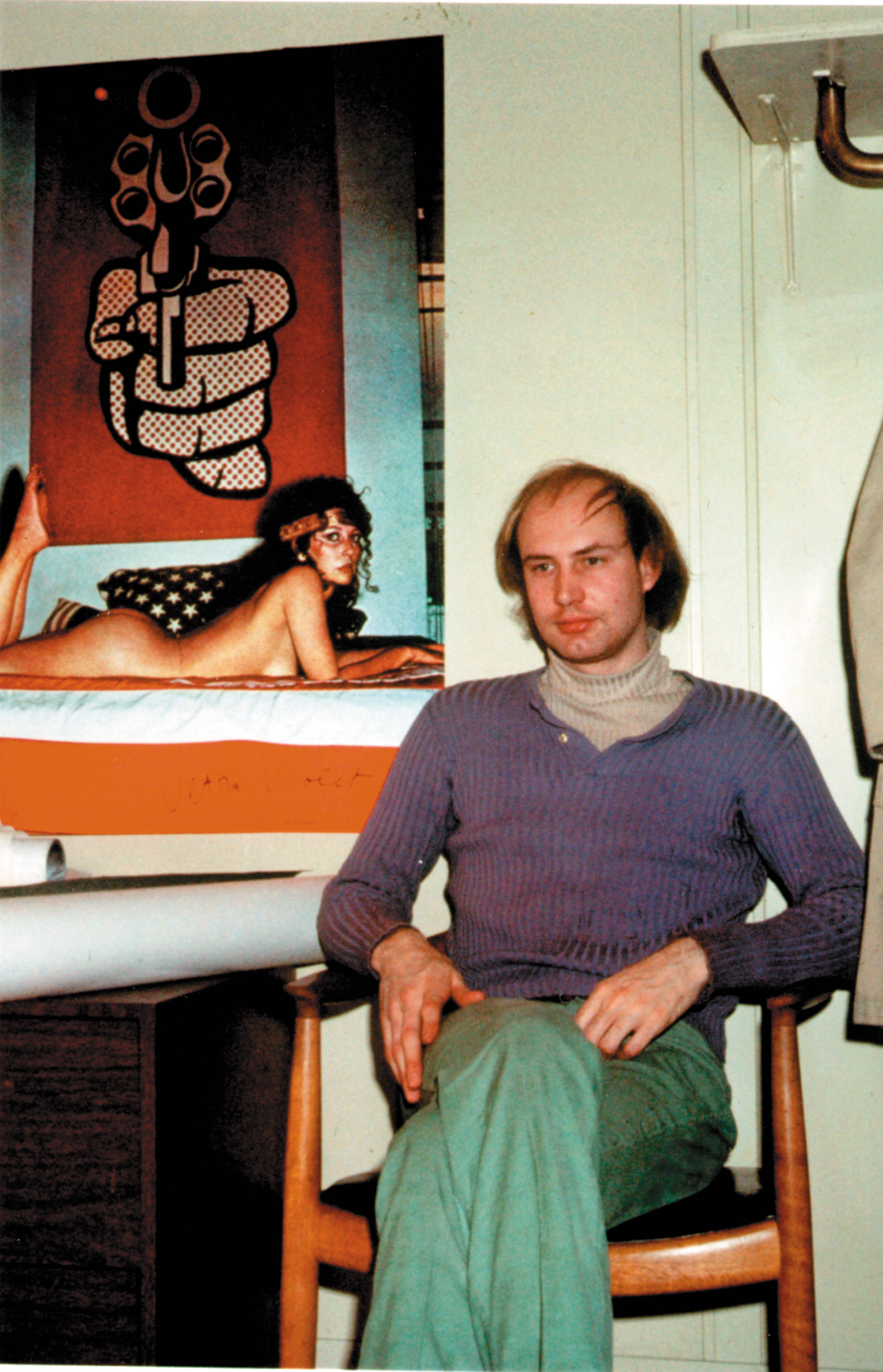

Douglas Crimp’s Before Pictures is the sort of book that can make its readers feel as if they have made an interesting friend (or at least an acquaintance) without the bother and awkwardness of getting to know an actual person. We hear our new friend’s favorite stories, polished to a high gloss, and gain access to a trove of memories, preoccupations, and regrets. Crimp, whose books include Our Kind of Movie: The Films of Andy Warhol (2012), On the Museum’s Ruins (1993), and Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics (2002), tells us about his aesthetic passions, his private life, and his career as an art critic, curator, and significant force in the downtown art scene during the final decades of the twentieth century.

His new book takes its title from the influential gallery exhibition “Pictures” that Crimp curated at the nonprofit Artists Space in 1977, and that is said to have christened the so-called Pictures Generation of artists. This group includes Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Richard Prince, and Laurie Simmons, though only Longo was included in the original show. Before Pictures is an immersion in the art and sensibility of a time and place, a portrait of a vanished world, and a cautionary lesson about how rapidly such worlds can vanish. Crimp tells us what it was like to be a gay man in New York during the celebratory period bookended by the Stonewall uprising and the AIDS crisis. Some admirable part of that spirit has persisted in Crimp, who remains grateful for the leather bars that existed “until Chelsea was transformed into an art district” and that he discovered after his arrival in New York. “I would have to learn how and where to be queer all over again, since being queer is a matter of a world you inhabit, not something you simply are.”

Beginning in the 1980s, with the essay “Mourning and Militancy,” a consideration of the relationship between grief and activism, Crimp has written extensively about AIDS and its effect on the individual psyche and the larger society. His spirited essay “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic” (1987) applauds

a new phase in gay men’s responses to the epidemic. Having learned to support and grieve for our lovers and friends; having joined the fight against fear, hatred, repression, and inaction; having adjusted our sex lives so as to protect ourselves and one another—we are now reclaiming our subjectivities, our communities, our culture…and our promiscuous love of sex.

Crimp recreates the fertile climate of prelapsarian Soho, when gifted and ambitious young artists could afford to inhabit drafty lofts with sketchy plumbing and manual elevators. It had only a few bars, fewer restaurants, and as yet no T-shirt stands, but it had a good bookstore, thriving galleries, Italian butchers and bakers, and most importantly, working artists who knew and respected one another’s work. It was a vibrant society soon to be devastated by disease and dispersed by skyrocketing real estate prices.

Crimp memorializes this milieu with affection: “I remember…hearing Philip Glass’s Music in Twelve Parts (1971–74) at an informal artist-loft gathering on a Sunday afternoon in SoHo. To enhance the experience, joints were freely passed among the listeners.” Precise details illustrate how much the city has changed. Now that fresh cilantro is available in local supermarkets, it’s startling to hear that in 1972, Crimp’s efforts to write a Moroccan cookbook were hampered by the difficulty of finding it in New York City.

Crimp grew up in a corner of northern Idaho so conservative that in 1996, his stepfather saw his “juice preference” as a radical threat to the social order: “My stepfather opened the refrigerator and, surveying its contents, bellowed, ‘What is this grapefruit juice doing here? We drink orange juice in this house!’” Though Crimp was in his early fifties, his relationship with his parents was too fraught for him to explain that he “had recently started taking an experimental antiviral medication for HIV that made orange juice taste strange.”

Much about Crimp’s daily life might well have outdone his stepfather’s fantasies of depraved East Coast fleshpots. In 1967, he took a leave from college in New Orleans and went to New York, where he got a job as an assistant to the brilliant couturier Charles James, by then reduced to domestic squalor in the Chelsea Hotel. Within weeks the job had lost its luster:

I resented having to do menial tasks like walking his beagle around Chelsea. I wasn’t happy that he was slipping amphetamines into my morning coffee. I couldn’t tolerate his tantrums. The last straw was his telling me that instead of paying me for my work he would open a charge account for me at Barney’s.

Among the copious, carefully chosen images accompanying the text are photos of the clothing that James designed and the interiors he decorated. Most notable of these was the de Menil house in Houston, designed by Phillip Johnson. “The moment you enter,” Crimp writes about James’s work on that project,

Advertisement

you face an acid-green velvet-upholstered Victorian settee, signaling that the furniture throughout will be a hodgepodge of periods, cultures, and styles and include, among James’s other creations, his Butterfly Sofa, inspired by Salvador Dalí’s 1936 Mae West Lips couch. This is decor gone berserk. If design is a crime, as we have been admonished, then this must be a lurid sex crime.

After graduating from Tulane, Crimp made another attempt on Manhattan. Walking from his Spanish Harlem apartment past the Guggenheim Museum, he decided to stop in and apply for a job. A guest curator had recently quit in the midst of organizing a show of pre-Columbian art, and Crimp, who had studied the subject in college, was hired. Three years later he was fired after a dispute about a large, site-specific installation by Daniel Buren; it was almost immediately removed. The work—a vertically striped canvas banner hung down the center of the atrium and a pattern of colored gels covered the skylight—was considered, by other curators and Buren’s fellow artists, to be overly decorative.

By then (or not long after) Crimp had met the people he wanted to meet, among them Richard Serra, John Ashbery, Jane Freilicher, Leonard Bernstein, and the Andy Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn. He’d also discovered a fun and exciting way to live: reviewing art, teaching just enough to pay the rent, hanging out at Max’s Kansas City, cruising the streets, picking up hot guys, and having affairs, some more fulfilling than others. He moved from the Upper East Side and Spanish Harlem to Chelsea, the West Village, and later to a spacious loft in Tribeca that featured a pedigreed refrigerator-freezer, a legacy from Jasper Johns. That last move “came about,” he writes,

as a result of my decision to get serious about being an art critic, to replace the gay scene with the art scene. I’d come to feel myself adrift, not accomplishing enough, not spending enough time with the crowd to which I “rightly” belonged.

Crimp summons up the pleasures of a summer in a small Fire Island town without electricity and the challenges posed by his relocation to a commercial building in the Financial District, where the lack of plumbing in his apartment forced him to use the public bathrooms down the hall. In 1978 a harrowing accident at the Empire Rollerdrome in Crown Heights, where the skating was “fierce,” left him with a broken hip. An encounter in Mantua five years earlier (“I was sitting on the steps of the basilica in the Piazza Andrea Mantegna when an attractive boy sped by on a Vespa and glanced my way”) inspires a reflection on the difference between gay cruising at home and abroad:

Apart from the Ramble in Central Park and parts of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, outdoor cruising in New York took place mostly at night in industrial zones of the city, behind parked box trucks or in abandoned piers. In Europe, by contrast, it occurred in some of the most beautiful parts of cities, the Tuileries in Paris, the Villa Borghese Gardens in Rome, and the San Marco Giardinetti boat platforms just off the Giardini Reali in Venice.

He writes lucidly and often affectingly about his passion for George Balanchine’s choreography, his fascination with the Watergate hearings, his collaboration with the performance artist Joan Jonas on an exhibition catalog essay, and the films and museum shows (in particular an exhibition of Balenciaga fashions) that influenced his ideas about art. He tracks the rise of gay men’s collective fixation on bodybuilding and considers the way in which the fluidity of disco dancing—alone, in couples, and in groups—“mirrored the ethos of gay liberation”:

Coupling was newly seen not as a “happily-ever-after” compact but as an in-the-moment union for sharing pleasure. Such pleasure sharing could, of course, lead to all kinds of longer-term relationships…. But it didn’t have to lead to anything at all. Pleasure was its own reward; it didn’t require redemption through love or commitment or even an exchange of phone numbers. Moreover, two stopped being a magic number: coupling could easily multiply to become a three-way, a foursome, group sex.

Crimp is a charming, gossipy raconteur with an instinct for a good story. We’re engaged by his account of being attacked by a flock of terns on the sand dunes on Cape Cod, and of a wedding at which Walker Evans volunteered to photograph the reception; every photo, except one, was of a “statuesque blond” whom Evans, “a bit of a lecher,” found attractive. In Nice he meets a former American showgirl, the wife—“if that is indeed what she was”—of Baron Bich, who founded the Bic company, “famous for its pens and lighters.” The baroness, who arrived for dinner in a floor-length ermine coat worn over jeans, was thrilled when Crimp’s companion reported having been impressed by the San Diego Zoo:

Advertisement

“My Joe, my Joe, that’s where my Joe is!” she squealed. Her Joe, it turned out, was a pet gorilla that…became Mighty Joe Young in the film of that title…. The baroness was overjoyed to learn that we had seen her Joe’s screen appearance and, moreover, in effect seen hers. She had worked behind the scenes in Africa with the baby gorilla, since only she could make the animal behave as the filmmakers wished.

In 1971 he made an arduous expedition with the painter Pat Steir to visit Agnes Martin, then living atop a mesa in New Mexico. Anyone who knew about Martin’s legendary predilection for solitude could have predicted that the meeting would be strained and unsatisfying. But Crimp narrates the story with humor and great sympathy for his younger self, callow enough to expect something meaningful out of a pilgrimage to the studio of a revered, reclusive artist:

I become very shy in the presence of someone else who is shy, and Martin was shy indeed. It was also obvious from where we were and how we got there that Martin had no social life; she surely passed days and even weeks with only her own thoughts as company. I still can’t figure out where the food she put on the table for us came from—where she could have bought it or how she kept it fresh. She certainly had no electricity up there on the mesa, though perhaps she had propane refrigeration…. Martin’s conversation was odd, gnomic—assertive and tentative at once…. Pat and I must have seemed just kids to her—Martin was fifty-nine at the time, and I was turning twenty-seven—so she might have thought we were there to learn from her wisdom. In fact, I’m not sure why we were there, except that we both loved her paintings.

Oddly, or not so oddly, the murkiest moments in Before Pictures occur when Crimp is writing about art and art criticism. Revisiting long-ago disagreements—one concerning the removal of Buren’s installation from the Guggenheim, another about who was included in or left out of the “Pictures” show at Artists Space and a later version at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—he assumes that his readers will be familiar with the substance of (and participants in) these quarrels; we sense that scores are still being settled even if we don’t quite understand what they are. But that’s less of a problem than the passages whose meaning resists the clarification that the conscientious reader may seek in the dictionary and the handbook of art historical terminology.

Of course there are exceptions, helpful and straightforward considerations of particular works, among them Crimp’s illuminating reading of Ellsworth Kelly’s drawing of two gingko leaves: “The gingko leaves stand on the page not as they might grow on a tree but simply one next to the other, two similar but distinct individuals.” But when Crimp quotes from his own 1973 review of Kelly’s paintings, it’s as if we are hearing another voice, the critical-academic voice perversely determined to make things harder for the reader. Such is often the case when he quotes from his earlier writings. Those outside Crimp’s field may struggle with passages like the following and wonder if the struggle was worth it:

“The problem,” I wrote, “was… to give the painted surface an equivalent literalness to that which Minimalism had imparted to the sculptural object. The specificity of a ‘specific surface’ is inherent in the quality of opacity, a quality that had been banished from painting when burnished gold surfaces gave way to pictorial spaces in the fourteenth century.” …Indeed, I meant opacity to be a direct rebuke to the supremacy of opticality as propounded by [Clement] Greenberg and [Michael] Fried.

Crimp is dismissive of the poets—Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, James Schuyler, and others—who wrote, often eloquently, for Art News but who, in his view, were slow to grasp the essence and the importance of “Conceptual art, Earthworks, and artists’ film, video and performance.” He had, he admits, scant enthusiasm for poetry: “I wasn’t a poet. I didn’t talk about poetry. I didn’t understand poetry. Eventually I stopped even trying to read poetry.” By the late 1970s, he had rejected the “poet-critic ethos” of Art News and embraced the poststructuralist theory–based criticism that dominated the magazine October, founded by Annette Michelson and Rosalind Krauss, with whom Crimp studied at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Beginning in 1977, Crimp worked as an editor at October, for which he would write essays with lines such as:

If it had been characteristic of the formal descriptions of modernist art that they were topographical, that they mapped the surfaces of artworks in order to determine their structures, then it has now become necessary to think of description as a stratigraphic activity.

Perhaps it’s unfair to single out such sentences. Crimp was only one of many who elected to write about art in this way. During the early 1980s, I was at a dinner at which the guests—writers and painters—each chose a recent art journal or exhibition catalog from a stack, opened it at random, and read a paragraph to the others, who then tried, mostly with little success, to decode its meaning. This was when much writing on art was so syntactically convoluted and clotted with jargon as to make it all but incomprehensible to the general reader. One felt that critics and academics were writing solely for one another. I remember thinking it counterintuitive to write so obscurely about art movements—Minimalism, conceptual and performance art—that were new, unfamiliar, and often perplexing to the museum and gallery audience.

Why make a difficult work seem less, rather than more, comprehensible? Why not try to explain why a Donald Judd sculpture or an Agnes Martin painting was important and beautiful (a word that fell into some disrepute during that time)? In the new book, Crimp—whose association with October ended around the time he became a more vocal member of ACT UP, the AIDS activist group—questions his “naive attempt to apply structural linguistics to art that returned to issues of representation.” Remarking on his essay on Martin, in which he noted that “the ratio of horizontal to vertical lines is 1:2, of unit rectangle height to width, 3:2,” he writes: “I was certainly closer to my high-school math classes when I wrote this than I am now.”

It’s somewhat different to read passages of obscure 1970s and 1980s art writing in 2016, when so much of our culture (except for the high-end art market) seems marginalized, threatened, economically hard to sustain. I find myself feeling great sympathy for anyone who cares so passionately about art; I’m thrilled when a writer mentions a Joseph Cornell box or the films of Jack Smith, and more careful about admitting to what extent art jargon gets under my skin.

At the same time, it has never seemed more important to be mindful of the balance between clarity and an overreliance on critical or academic buzzwords. Don’t we want others—those not like us—to be able to see what we see? Happily, much current writing about art has taken a turn toward the light. No one would claim that art criticism is now jargon-free, but the specialized terminology is less likely to be that of poststructuralism than of politics and technology.

Though its central subject is the author himself, Before Pictures is the least self-conscious and self-serious of Crimp’s books, and consequently the most appealing. It’s heartening to see a writer grow more lucid, incisive, and quirkier as his career progresses. We want to hear what Crimp has to say about what he’s witnessed and experienced, about the places and people he’s met, the fashions and movements that are part of our history, and that are being rinsed from history by a tide of cultural and social change. Before Pictures cites a series of collaborations between artistic geniuses, performances that could only be seen for a short time and at which Crimp was fortunate and smart enough to be present:

I’d seen very little dance since my first ecstatic exposure to it in winter 1970 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where Merce Cunningham’s company performed RainForest (1968), with Andy Warhol’s helium-filled Silver Clouds as the set and music by David Tudor; Walkaround Time (1968), with Jasper Johns’s clear plastic rectangular elements printed with images from Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass, to the music of David Behrman; Tread (1970), with a set by Bruce Nauman of industrial pedestal fans evenly spaced across the proscenium, half of them blowing toward the audience, and music by Christian Wolff; and Canfield (1969), whose set by Robert Morris was a gray columnar light box that moved back and forth on a track, also across the proscenium, illuminating the stage as it moved, with music by Pauline Oliveros.

Many of the people who might want to see these performances now were born too late. Happily, we have Douglas Crimp to make it possible for us to imagine what they must have been like.

This Issue

December 21, 2017

Lies

Kick Against the Pricks

The Man from Red Vienna