Despite the durable tale of liberation from Victorian repression, American history during the early twentieth century was less a linear drive toward emancipation than a recasting of centrifugal and centripetal forces. The two tendencies coexisted, calling each other into being, sometimes within the same cultural figure. Consider the chorus girl, whose vibrant sexuality was constrained by close-order drill; or the militant imperialist, whose lust for vicarious risk was countered by a dream of regimented order.

The interplay between new sources of chaos and new ways to contain it characterized the epoch as a whole. Centrifugal forces arose from exploding markets for labor, goods, and entertainment; from women’s demands for personal autonomy and a larger part in public life; from immigrants of multiple ethnicities crowding into cities and striking workers filling the streets; and from a vague but pervasive fascination with Force (invariably capitalized), which seemed to be quickening pulses as never before. Yet this ferment coexisted with centripetal forces, embodied in new idioms (hygiene, normality, scientific racism, managerial rationality) and new institutions (monopolistic corporations, government bureaucracies)—all of which channeled and contained the energies unleashed by modern urban life.

The apparently hedonistic culture that emerged before World War I was a muddle of flagrant gestures toward personal liberation and subtle new forms of social coercion—the spread of compulsory heterosexuality in the guise of sexual freedom, the standardization of ideals of health and beauty through national advertising, the codification of racial hierarchies in an ideology of empire, and the imposition of higher standards of efficiency in the workplace as well as unprecedented demands for conformity in the public sphere. The loosening of strictures on personal behavior coincided with the creation of new definitions of what was permissible and normal, which advanced under the banners of progress and liberation. Early-twentieth-century American society was on the verge of a reshuffling of values and power relations in which the rich would come out just fine. And New York City was where that new synthesis would be worked out, in all its messy and contradictory details.

Mike Wallace knows this. In fact he knows nearly everything worth knowing about New York during the years leading up to World War I. He knows where the Heinz Company mounted the biggest electric pickle in the world (Madison Square), how Sophie Tucker started out as a “World-Renowned Coon Shouter,” how many pounds a typical longshoreman loaded in an hour (three thousand), and how the City College of New York (CCNY) became “the Jewish University of America,” despite expecting its students to check their religion and their radical politics at the gate.

Wallace packs these and a multitude of other fascinating details into his enormous book, Greater Gotham, which somehow remains astonishingly readable. But he also gets the big picture right—the balance of cultural tensions, the centrifugal exuberance vs. the new forms of power and control. He never forgets that early-twentieth-century New York was awash in global flows of capital and embedded in regional, national, and international markets. And he knows that every liberation, no matter how genuine, contains the possibility of renewed constraint. One could not ask for a more thorough or thoughtful guide to the emergence of New York as the Empire City.

The consolidation of the five boroughs into Greater Gotham, in January 1898, coincided with the beginning of a corporate war on “ruinous competition” that created Standard Oil, General Electric, US Steel, and other titanic monopolies, mostly midwived by the House of Morgan. Freed from fear that the Democrat William Jennings Bryan would be elected president in 1896, investors poured capital into the firms traded publicly on Wall Street, sustaining a run of mergers that lasted six years. Consolidation was in the air.

So was empire. New imperial possessions and protectorates—Puerto Rico, the Philippine Islands, Cuba—became magnets for New York capital. James B. Duke, who had just moved the headquarters of his American Tobacco Company to New York, took his American Cigar Company to Cuba. Other businessmen followed his lead. Soon 85 percent of the island’s tobacco manufacturing was owned by Americans, and 90 percent of its exports went to the United States. The pattern quickly fell into place: “Washington would ride shotgun on Wall Street’s stagecoach,” Wallace writes.

But empire was about military glory as well as commercial profit, and New York would not be outdone on that front either. “Surely no Roman general, surely no Roman Emperor ever received such a tribute from the populace of the Eternal City,” The New York Times declared of the tribute Admiral George Dewey, the victor of the Battle of Manila Bay in the Spanish-American War, received from the thousands who turned out for the parade in his honor that the city held in 1899. Fears of imperial hubris, voiced by republican moralists from John Quincy Adams to William James, melted away amid fantasies of New York as a second Rome.

Advertisement

The foundation of the fantasies was money. Capital began flowing from Wall Street to Europe in 1900, as Great Britain struggled to meet the mounting costs of the Boer War. Money managers pooled capital by creating syndicates, interlocking directorates, and gentlemen’s agreements—deals done in downtown dining clubs. Muckraking critics caught the scent of corruption and exposed “Frenzied Finance” in emerging mass-circulation magazines.

Middle- and upper-class citizens who feared being fleeced took to calling themselves “progressives.” Their hero was Theodore Roosevelt, a scion of the Anglo-Dutch elite who lived on his investments but sought to rein in conscienceless capital—though as the steel baron Henry Clay Frick recalled, Roosevelt “got down on his knees before us” begging for contributions to his 1904 presidential campaign. “We bought the son of a bitch but he didn’t stay bought,” Frick complained. When J.P. Morgan and other prominent bankers succeeded in stopping the Panic of 1907, progressives raised alarms about private bankers’ control over public life, demanding regulation of the “money trust.” The result was the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which appeared to curb the concentrated power of New York banks but actually legitimated it.

Like money power, political power was centralized in a powerful institutional structure. Progressive reformers kept trying to wrest control of it from the Tammany Hall Democratic machine, with occasional success. They increasingly promoted the influence of self-proclaimed neutral experts operating out of organizations like the Bureau of Municipal Research and promising to replace corrupt patronage with efficient administration by the competent. In 1913 the (mostly Protestant) reformers backed the mayoral candidacy of the Irish Catholic John Mitchel, who reorganized city finances by borrowing to promote metropolitan growth and raising real estate values—and with them tax revenues.

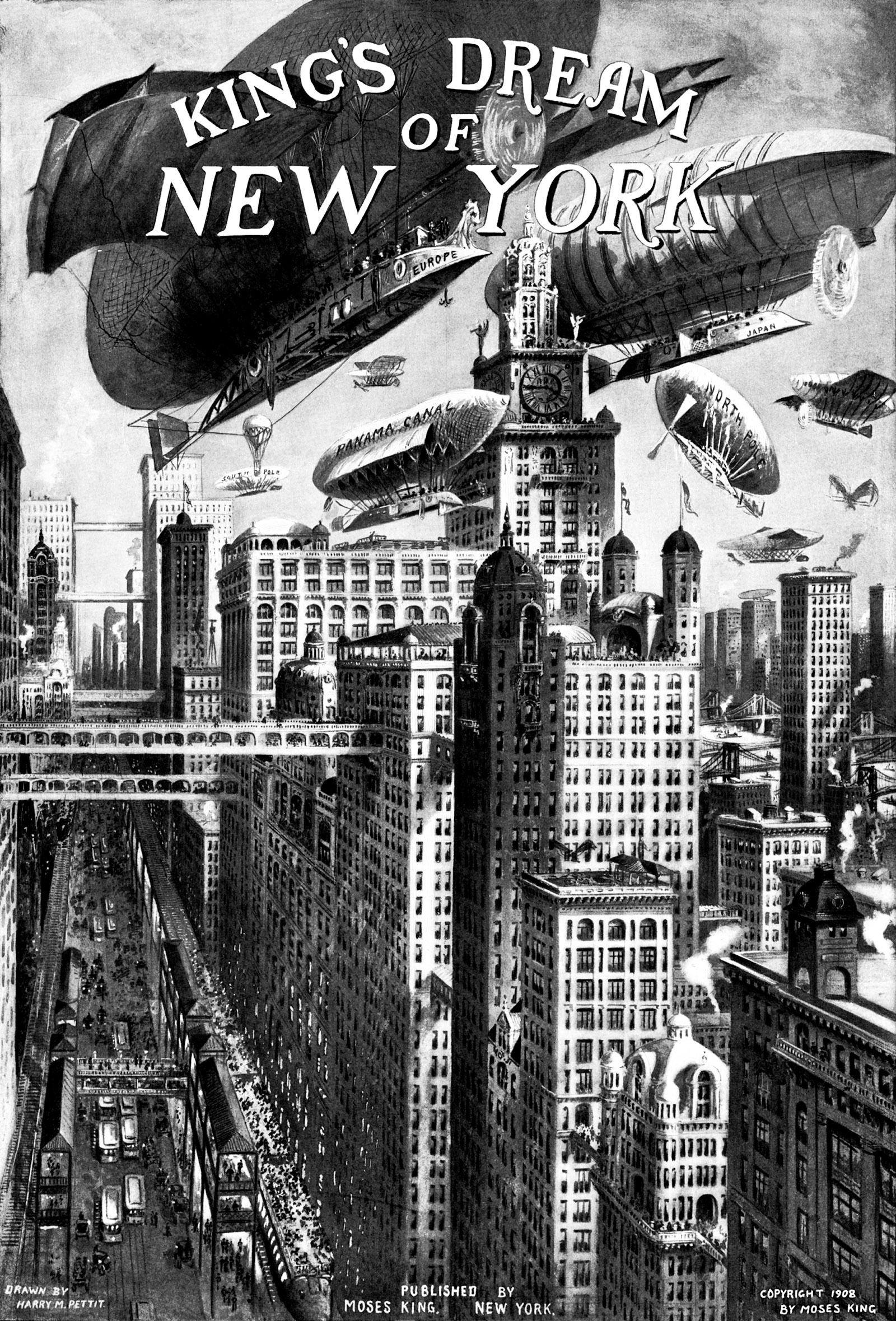

The growth was already underway, upward as well as outward. The builder Harry Black had hired Daniel Burnham to design the Flatiron Building, which went up in 1902 to widespread amazement and acclaim. It was the beginning of what Wallace calls a “Sky Boom” in tall buildings. In less than a decade, the skyline replaced the harbor as New York’s emblem.

Skyscrapers epitomized the coexistence of centripetal and centrifugal force. They were the embodiments of America’s consolidating and internationalizing corporate economy. Outsize variants of Heinz’s electric pickle—the Singer Tower, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Building, the Woolworth Building—aimed to enhance brand recognition among an emerging mass of consumers. Symbols of corporate identity, they strove to evoke emergent empire but also traditional civic authority, as Met Life did with its Venetian bell tower. Yet despite their sponsors’ dream of order, skyscrapers went up in what Wallace calls a “Promethean frenzy” of construction.

Intellectuals found tall buildings exhilarating. “Here is our poetry,” said Ezra Pound in 1910, “for we have pulled down the stars to our will.” The young Lewis Mumford, viewing Manhattan from the Brooklyn Bridge, agreed: “Here was my city, immense, overpowering, flooded with energy and light.” These were early expressions of what became a characteristic New York rhapsody: the urban sublime.

Henry James was less impressed: “Skyscrapers are the last word of economic ingenuity only till another word be written,” he observed. “The consciousness of the finite, the menaced, the essentially invented state twinkles ever, to my perception, in the thousand glassy eyes of these giants of the mere market.” James caught the “aura of temporariness,” in Wallace’s words, that suffused lower and midtown Manhattan; it arose from the city’s refusal to interfere with property owners’ right to do anything they wanted with their property. The tallest skyscrapers did not remain tallest for long, and even the most magnificent could be torn down in less than a decade.

Straining to tie its parts together, the city kept flying apart. The completion of the subway system made access to Greater Gotham an everyday experience, but the emerging car culture created a new source of chaotic movement and class conflict, as innocent urchins were regularly run down by rich twits. Yet Scientific American predicted that the swift noiseless movement of cars over clean (horseless) streets “would eliminate a greater part of the nervousness, distraction, and strain of modern metropolitan life.” Even chuffing cars could be integrated into visions of a well-managed utopia.

Street-level class conflict surfaced as retail commerce moved to midtown. By the 1910s, Fifth Avenue was full of cavernous bazaars offering women shoppers escape from domestic propriety into a glamorous commercial public sphere. The only problem was the scruffy crowd—mostly garment workers on lunch break—that jostled the ladies in the street. Upscale retailers fought back, and in 1916, they managed to zone manufacturing out of the rectangle formed by 33rd to 59th Streets and Third to Seventh Avenues.

Advertisement

As the battle over Fifth Avenue shopping suggested, class conflict was nearly always shaped by interethnic hostilities. Italians and Russian Jews joined Irish and Germans in the restless horde that provoked anxiety among the Anglo-Dutch elite. The anxiety was most acute when the working classes overcame their own ethnic rivalries and began to form industrial unions. But that took some doing. Samuel Gompers’s American Federation of Labor was committed to trade unionism, which tended to fragment along craft and ethnic lines—German cigarmakers, Irish ironworkers.

The needle trades were different, partly because of their Jewishness. By 1914, New York City had the greatest number of Jews in the world, many of whom were committed to socialism and worked in the needle trades. The mechanization of the garment industry was well underway, as production shifted from sweatshop to factory. More workers were consolidated in one place, which made them easier to organize. “It is a regular slave factory,” said the radical organizer Clara Lemlich. “Not only your hands and your time but your mind is sold.” Garment workers’ locals gravitated toward the Women’s Trade Union League and enlisted upper-class allies, including Anne Morgan (J.P.’s daughter). Tensions among workers arose between Italians and Jews, and among owners between the “cockroach capitalists” who still operated sweatshops and the more established capitalists who wanted to drive them out of business. Concentration of force was the order of the day, for management and employees alike.

The Italian–Jewish conflict had political resonances. Many Italian artisans were displaced labor militants who inclined toward anarcho-syndicalist strategies—a decentralized communitarianism centered on small groups of workers asserting control over their workplace. Jewish radicals tended to be socialists and parliamentarians. When the Industrial Workers of the World appeared on the scene, led by a one-eyed giant from the Far West called Big Bill Haywood, anarcho-syndicalism acquired a forceful presence. Haywood urged “sabotage” in the workplace, by which he meant work slowdowns. He debated the Socialist Party leader Morris Hillquit in the Great Hall of the Cooper Union, where Hillquit insisted on the power of the ballot box. The election of 1912 appeared to vindicate Hillquit’s strategy: the Socialist Eugene Debs won a million votes, 6 percent of the total. This was unprecedented and seemed to offer an electoral foundation to build on. Haywood was expelled from the Socialist Party.

Politics and culture intertwined. In the elite imagination, immigrants were easily equated with anarchists, and vice versa. Feeling engulfed, custodians of culture counterattacked, creating and revitalizing institutions to assimilate, uplift, or inspire the immigrant masses—ranging from CCNY and the new, uptown Columbia University to the Brooklyn Museum, the Bronx Zoo, and the New York Public Library, not to mention the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Metropolitan Opera.

The last was a case study in ethnic tensions, as Protestants clustered cheek by jowl with assimilated German Jews—among them the dapper, cultivated Otto Kahn, a partner in the Wall Street investment firm Kuhn, Loeb. Despite Jews’ financial backing of the Met, they were not allowed to buy their own boxes (though an exception was made in 1917 for Kahn, its biggest shareholder and patron). This was the sort of genteel anti-Semitism that prompted Kahn’s sardonic remark: “A kike is a Jewish gentleman who has just left the room.” The Met increasingly employed Italian performers, led by the tenor Enrico Caruso, who became embroiled in controversy when a woman accused him of pinching her buttocks in the Monkey House at the Central Park Zoo. Wallace thinks “The Monkey House Scandal” was probably a frame-up; in any case it did nothing to damage Caruso’s popularity. “New York still loves me,” he told the press.

The conflict between an obstreperous multiethnic mass audience and elites attempting to control it is a familiar but inadequate trope in cultural histories of the period. Wallace transcends this formula by recognizing that strategies of control also originated among ethnic entrepreneurs who were struggling to regulate the flow of products out of New York and into the nation’s theaters—in effect standardizing New York–based entertainment for a national mass audience. The most successful was the Shubert Organization, the creation of two ambitious Jewish impresarios, which came to control 75 percent of theater tickets sold in the United States. Meanwhile popular music was also becoming more industrialized and centralized in songwriting firms dominated by assimilated German Jews on 28th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues—the block that came to be called Tin Pan Alley, for the din of pianos one could hear from the street.

Amid all the standardization, a spectacular nightlife arose around Times Square. Much of the excitement was the setting itself, which was transformed by Oscar Gude, New York’s master of outdoor advertising and the designer of Heinz’s fifty-foot pickle. Hired by advertisers for humble products like beer and bran flakes, cigarettes and chewing gum, Gude transformed Times Square into what the British writer Arnold Bennett called “an enfevered phantasmagoria” of moving electric images—girls walking tightropes, boys in shorts boxing. Times Square joined Coney Island as an entertainment zone.

But Coney Island was in a class by itself—“the most popular resort on the planet,” according to Wallace, and also a suggestive expression of mass culture as an antidote to daily life. The extravagant constellation of amusement parks was an early example of what became a common practice—the mass marketing of remedies for the disorders bred by mass society. As Wallace writes (summarizing “radical analysts”): “Attendees were offered and consumed scientifically managed and industrially engineered experiences. They were turned into articles on a movable assembly line. The only things turned upside down were the patrons.” Coney Island captured the careful management of consumers that characterized mass culture.

Still there were some areas where the new energies were too intense to be easily managed—particularly those where African-Americans influenced entertainment styles. That influence was often hemmed in by caricature: the black performers Bert Williams and George Walker made their vaudeville debut in 1896 as “Two Real Coons.” At about the same time, the composer James Reese Europe, the writer James Weldon Johnson, and other black cultural figures created a (temporarily) thriving cultural scene at the Hotel Marshall on West 53rd Street, where musicians could make connections that might lead to employment. Ragtime piano players were everywhere, and their music was influencing the likes of Irving Berlin. Bert Williams became the black star in Florenz Ziegfeld’s revue, a counterpoint to the sanitized white sexuality of the chorus girls.

But what really brought race and sex together was the Dance Craze of 1911–1913. Animal dances proliferated—the Turkey Trot, the Bunny Hug, the Grizzly Bear. The psychoanalyst A.A. Brill was certain that this was a return of the repressed. Dancers imitated animal movements and engaged in mock sex, loins pressed together. Commercial dance halls offered unprecedented opportunities for cross-class and cross-race mixing. Swarthy Italians could serve as “tango pirates,” but the black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar caught the fundamental dynamic of the dance hall with these lines from the musical revue In Dahomey: “When dey hear dem ragtime tunes/White fo’ks try to pass fo’ coons.” Moralists’ “deepest worry,” Wallace writes, was “dance-driven sexual congress between white women and black men.”

All this could be dangerous for black men. New York was a Jim Crow town. In movie theaters, black people were consigned to the balcony—“nigger heaven.” On the street, police brutality was routine. As veteran cops told rookies: “‘unlawful resistance’ covers a multitude of sins.” Small wonder that in 1904, when the Lenox Avenue subway arrived uptown and a young black developer named Philip Payton started evicting whites from his apartment buildings and renting them to blacks, Harlem became a magnet for African-Americans from throughout the city, as well as from the rural south.

A smaller and more scattered population was also headed for Gotham, as Greenwich Village began attracting would-be bohemians from the provinces—Mary Heaton Vorse from Amherst, Massachusetts; John Reed from Portland, Oregon; Floyd Dell from Davenport, Iowa. If an aspiring bohemian woman had a feminist bent, she might join Heterodoxy, “a little band of willful women” that met at Polly’s Restaurant in the Village to provide a forum “for women who did things and did them openly.” Village feminists in general emphasized sex as personal fulfillment, but a broader shift in sexual attitudes tended toward compulsory heterosexuality, along with the invention and pathologizing of “homosexuality.”

Artists, like feminists, were committed to transcending “genteel protocols”—especially the marriage of Morality and Beauty. John Sloan, George Bellows, and the other painters who proudly embraced the label “Ash Can School” all loved the “fabulous energy and dynamic busyness” of crowds scurrying for a subway and “the real ‘vulgar’ human life” of immigrant kids capering down Delancey. But what really posed a challenge to American ways of seeing was the Armory Show, the legendary exhibition in 1913 that introduced Americans to European modernists. Among them, Francis Picabia in particular deployed a futurist rhetoric that resonated with the urban sublime. He painted skyscrapers, he said, to catch “the rush of upward movement, the feeling of those who attempted to build the Tower of Babel—man’s desire to reach the heavens, to achieve infinity.” The same sentiments inspired Joseph Stella’s admiration for New York’s “violent blaze of electricity,” its permanent light show that epitomized what Picabia had dubbed “the futurist city.” New York was all about Force, all the time.

The forces of order and stability continued to assert their claims as well. Florence Kelley fought what the Social Gospel minister Walter Rauschenbusch called “institutionalized sinfulness” by leading public health campaigns against the tuberculosis that thrived in tenements and the adulteration that pervaded the food industry. Other progressives sought to assimilate immigrants by standardizing public education—lifting them “out of the swamp in which they were born and brought up,” as one reformer put it. Another sort of progressive crusaded against commercial vice, driving it into private venues; the high-end prostitute known as the “call girl” appeared on the scene. The centripetal force of government was policing behavior once thought exempt from public scrutiny.

The coming of World War I brought unprecedented pressures for regimentation. The Anglo-Dutch elite began a sustained assault on “hyphenated Americanism.” Roosevelt himself preferred coercive Americanization to immigration restriction. This was the enlightened progressive view; few paid much attention to the cogent calls of Horace Kallen and Randolph Bourne for a pluralistic, “Trans-National America.” Uniformity trumped multiplicity.

After American entry into the war, centripetal forces intensified. The Espionage Act of 1917 criminalized even casual utterances if they could be deemed disrespectful to flag or country. Vigilantes patrolled the streets of New York, searching for “slackers” who had not registered for the draft or answered the call-up. “Bolshevik” emerged as a new epithet for radicals and subversives. The drive for order culminated when the 1919 strike wave was used to justify a nationwide Red Scare that led to the deportation of thousands of radicals. New York Governor Al Smith eventually denounced the overreach as the prelude to the imposition of a police state. It was not a moment too soon.

In March 1917, Leon Trotsky returned to Russia from the Bronx, where he had been sojourning for just over two months after being deported from Spain. “I was leaving for Europe,” Trotsky recalled, “with the feeling of a man who has had only a peep into the foundry in which the fate of man is to be forged.” But what was the common fate that was being forged in New York? Devotees of the urban sublime did not address the question and only occasionally reflected on New York’s world-historical significance, beyond ritual celebration. One of those occasions was in 1902, when Harper’s Weekly traced the city’s ceaseless tumult to the nation’s newfound prosperity, which was centered in New York. Commerce pulsed through the streets as “an electrified current of financial strength that is charged with an energy unknown before in the field of human endeavor.” The “mighty force” astir beneath Gotham was money.

What Harper’s failed to acknowledge was that the effects of that force on everyday life were not always liberating. Investment capital created the subway system, which most people rode at “rush hour,” when they were going to and from work. At such times, one tour guide noted, “to do as the crowd does, is almost compulsory.” The routine of office and factory exacerbated the periodic crush of mass society. The city exerted its own centripetal forces, through the pressure exerted by its crowds, but also through the various forms of social discipline exacted by the employers, managers, and owners of capital. Power mattered, and capital was its instrument. But so, it turned out, was government. The mass mobilization of thought demanded by the war effort revealed how times could come—who knew when or how often?—when the requirement “to do as the crowd does” would be “almost compulsory” by fiat of the state. Freedom in the kingdom of force was always provisional.

This Issue

December 21, 2017

Lies

Kick Against the Pricks

The Man from Red Vienna