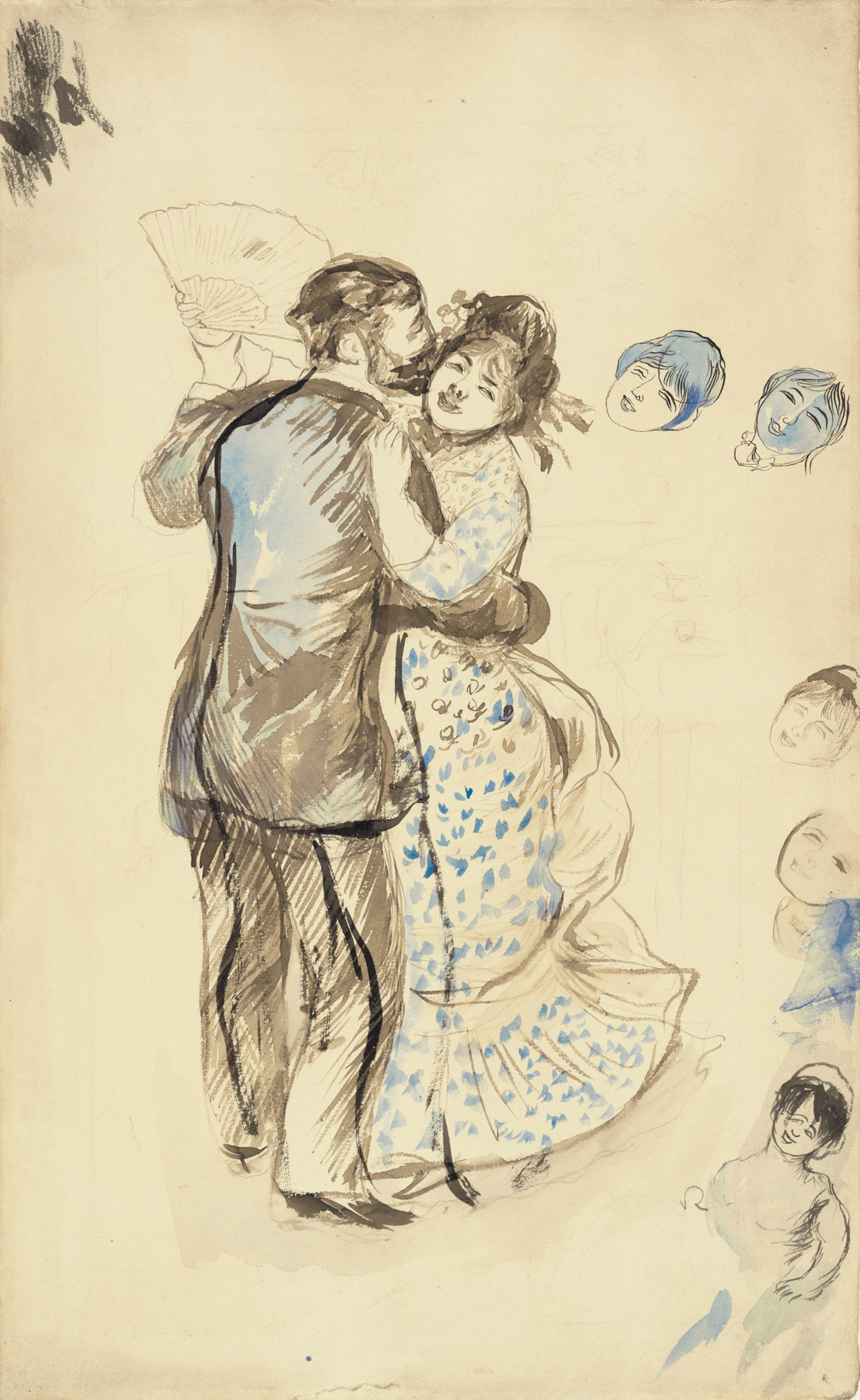

Opinion remains unsettled about Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who died nearly a hundred years ago, in 1919. There are museumgoers who recoil from what they regard as the saccharine sweetness of his portraits and nudes, which earned him a place among the most universally beloved artists of the twentieth century. Some suspect that this essential figure in the Impressionist avant-garde was at heart a conservative who turned his back on his fellow experimentalists as soon as he could. The monumental female figures that Renoir painted in his later years, although fervently admired by leaders of the modern movement including Bonnard, Matisse, and Picasso, are often dismissed as absurdly hyperbolic evocations of an antiquated femininity. The enormous arms, breasts, hips, and thighs that stirred Renoir’s imagination are seen as an affront to modern standards of beauty and health. Renoir is forever caught between the rival claims and allegiances of the avant-garde and the rearguard.

A new biography of Renoir and an exhibition devoted to one of his most important paintings are the latest attempts to navigate this perilous terrain. The challenges that he poses to interpretation are conquered by neither the biography, by the art historian Barbara Ehrlich White, nor by the exhibition and accompanying catalog that the Phillips Collection has devoted to Luncheon of the Boating Party, one of the treasures in that remarkable museum. Nobody seems to know how to present a satisfactory defense of Renoir’s silken brushwork, which is so often dismissed as glib and superficial.

The truth is that Renoir’s painterly gifts serve a vision that is not so much lighthearted as it is implacably hedonistic. In our time, when so many associate seriousness with the agonized imagery of Edvard Munch, Alberto Giacometti, and Francis Bacon, there is a danger that the heartfelt sweetness of Renoir’s work is confused with middlebrow sentimentality. Renoir sought sublime sentiments in the faces of beautiful young women and could not always avoid kitsch; he sometimes aimed for honey and produced only corn syrup. But in his very greatest paintings—from Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880–1881) to the portrait of the brilliant Austrian actress Tilla Durieux (1914), posing in her glittering costume for George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion—he takes his place with Titian, Rubens, Watteau, Matisse, and Bonnard among the immortal poets of pleasure.

No work of Renoir’s brings us closer to the paradoxical nature of his genius than the nearly six-foot-wide canvas Luncheon of the Boating Party. His subject is a gathering of more than a dozen of his friends on the terrace restaurant of the Maison Fournaise, an establishment on the island of Chatou some nine miles northwest of Paris. Here the intoxicating color and calligraphic brushwork of the Impressionists provokes a dazzling sensory overload, even as Renoir’s appetite for narrative and characterization brings to mind the vast historical and religious compositions of the Renaissance and the Baroque. This is an unexpected and indeed unprecedented convergence of painterly experimentalism and what some might dismiss as old-fashioned storytelling. It is a synthesis by many measures doomed to fail. But what we have instead is one of the great balancing acts of nineteenth-century art. Perhaps it’s precisely the dissonance of the conception that enables Renoir to capture, more completely than any other artist, the free-spiritedness of bohemian life in late-nineteenth-century France, when men and women knew how to turn a sun-dappled afternoon on the banks of a great river into the perfect occasion for conversations, flirtations, and daydreams.

Luncheon of the Boating Party is a beguiling hullabaloo of a composition. Renoir paints a table at the end of a meal—a table en déshabillé—with nearly emptied glasses, wine bottles full and not-so-full, a half-eaten bunch of grapes, dishes helter-skelter, and crumpled white linen napkins. There are a couple of men in straw hats wearing the white singlets that boaters favored, which leave their arms bare. One of these men sits backwards on a chair, as casual as can be. A woman plays with a little dog. People talk or stare into space. Many of Renoir’s friends posed for the painting and some are easily identifiable, while other figures may be composites of several people. In the catalog of the exhibition there is much discussion of who was the model for whom.

There is no question that the young woman in the lower left who is almost kissing the little dog she holds is Aline Charigot, who became Renoir’s wife in 1890. The man in the right foreground sitting backwards on the chair is based on Gustave Caillebotte, an adventuresome realist painter who was wealthy enough to become a collector of the work of his fellow Impressionists. The collector and connoisseur Charles Ephrussi—a friend of Proust’s—appears in a top hat in the back of the painting. The names of several actresses have also been associated with the composition. This is a work that maps a certain art world with devil-may-care ease. We see some of the artists, the critics who wrote about them, the collectors who supported them, and the actresses and other women with whom they consorted.

Advertisement

Renoir was by no means the only painter of his day who aimed to become what Baudelaire had dubbed the Painter of Modern Life. Manet, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Seurat reimagined modern life as a glorious tapestry, with each individual element a piece of a larger puzzle. Renoir approached that unifying vision with The Moulin de la Galette (1876), in which Parisian nightlife becomes one great indigo arabesque. But he also yearned for a documentary particularity that Impressionism, with its emphasis on sensory immediacy, could not necessarily contain. Going through the exhibition, a museumgoer can see how fervently Renoir embraced, during much of the 1870s, the Impressionist desire to dissolve naturalistic form into glittering, glancing sensory experience. But he cared too much for actualities—a woman’s complexion, a beautifully made hat—to experiment with the near abstraction that interested his friend Monet.

Renoir was a storyteller, and Luncheon of the Boating Party stands, with some of the tales of Maupassant and Daudet and certain scenes in Henry James’s The Ambassadors and Flaubert’s Sentimental Education, among the imperishable records of love and friendship in modern France. Renoir brought to the painting a savory synthesis of realism and romanticism. He was both the journalist who documented the leisure pursuits of his friends and the mythologist who granted his contemporaries some of the magnetism of demigods. In that sense he was a contemporary of Proust, who in certain pages of his great novel reimagined Paris as Parnassus.

Barbara Ehrlich White spends relatively little time discussing Luncheon of the Boating Party or for that matter discussing in much detail any of the paintings. That is only one of the many frustrations of her biography. White has dedicated her career to Renoir and has already published a great deal about him; I have no doubt as to her deep sympathy for the man and his art. A biography would seem a natural next step for her, except that she isn’t much of a writer. She knows everything about Renoir but relatively little about what do with what she knows.

White begins somewhat defensively, with a gentle takedown of another book, Renoir, My Father, the lush and lapidary biographical memoir that the artist’s second son, the great filmmaker Jean Renoir, published in 1958. She argues that in that earlier account of the artist’s life “the character and personality of Renoir remain elusive.” White is proud to put on display some skeletons discovered in the family’s closet, especially two children Renoir had with a woman by the name of Lise Tréhot, before he met Aline Charigot; neither child was kept by their parents and one was apparently never heard from again. White may feel that Renoir’s son turned his father’s life into too much of an idyll, but her own account fails to harness the emotional possibilities to be discovered in the actualities of the life.

Renoir was born in 1841 in humble circumstances; his father was a tailor and his mother a seamstress. Around the age of thirteen he was forced to leave school—the family finances were perilous—and he began an apprenticeship painting porcelain. By his mid-twenties he had found his way to the center of a group of artists, among them Monet and Cézanne, who were rethinking the very look of the natural world. Along with them he gradually found a following among a few adventuresome dealers and collectors. In his later years, at last enormously famous and free from money worries, he struggled with rheumatoid arthritis. He was an invalid, often incapable of walking, with gnarled, paralyzed hands, yet he somehow still managed to keep a tight grip on his brushes and paint the miraculous works of his final phase.

Aline was Renoir’s lover for a number of years and bore him a son, Pierre, before he finally married her. She was never an active participant in his intellectual and artistic life; that role almost invariably went to the men in his circle, although there were exceptions, especially his great friend the painter Berthe Morisot. White has the documentary evidence to support her belief that there was a good deal of “friction” between husband and wife. “Aline,” she reports, “had always pursued more luxury and comfort than Renoir desired.” Renoir was frustrated that his wife couldn’t rein in the eating and weight gain that left her with uncontrolled diabetes. She was jealous of Gabrielle, the young woman who began as a nanny and a model in the Renoir household and remained to care for the invalid artist. And he could be secretive, although his unwillingness to let Aline know about the illegitimate daughter to whom he remained devoted could be interpreted as an act of kindness.

Advertisement

What White cannot bring alive is the profound bond that linked these two quite different people. There is a remarkable letter from Renoir to Aline from around 1879. In response to her worrying that her soft, fleshy, sensuous looks make her ugly, he responds with a lover’s gentle ardor. “You are far from ugly,” he writes at first. “Actually, you are as beautiful as anyone could be.” Then he goes further, arguing that what binds them defies any simple definition of beauty. “I do not know if you are pretty or ugly,” he pursues, “but I do know that I have a strong urge to misbehave again.”

This passionate letter does come from early in their relationship. But whatever their later disagreements, I am not convinced that they were as definitively estranged as White would have us believe. I think she makes too little of the rather extraordinary fact that in 1901, when both Renoir and his wife were in anything but the best of health, they had a third son, Claude, nicknamed Coco. Something still resonated between them. Aline may not have understood much of anything about her husband’s most radical artistic ambitions. She may have hungered for a kind of high-bourgeois luxury that he rejected. Nevertheless, I find it difficult to imagine that a woman who had long ago taken her chances with an impecunious young painter—a man as wiry and excitable as she was heavy and settled—didn’t understand on some deep, instinctive level what he was about.

We cannot really grasp Renoir and Aline and their marriage without recognizing that Aline was Renoir’s muse, a woman whose image he treasured when she was young and later reclaimed in the younger women who modeled for him. Muses are out of fashion today. We recoil from anything that suggests objectification or idealization. But I don’t think it’s beyond possibility that Aline, who threw in her lot with a man who painted her as if she were a lusty angel, was gambling on immortality. Well before they had married, in Luncheon of the Boating Party, Renoir made of her one of European art’s most imperishable images of pure, sensuous pleasure. Aline, the beautiful young woman who clutches the adorable little dog, certainly knew that her lover had bestowed upon her a gift that no amount of bickering, disagreement, or neglect could erase.

Renoir’s feelings for Aline endured. In 1910, he painted a portrait of his now immensely overweight wife holding a little puppy; I wonder if he saw in that dog a reprise of her immortal part three decades earlier in the Boating Party. In Renoir’s climactic portrait of his wife, she is as gravely beautiful as the ancient Roman matrons who had been immortalized in marble centuries earlier.

What eludes White are the complexities of human nature. A case in point is her awkward treatment of Renoir’s position during the Dreyfus Affair, when, she rather glibly writes, he “got on the anti-Dreyfus bandwagon,” siding with those who believed that the Jewish officer was a traitor. White explains that in an earlier book she had taken the view that Renoir was anti-Semitic, but that she has now changed her mind, somehow exonerating him with the observations that “prejudice against the Jewish people was commonplace in late nineteenth- and early-twentieth century Europe” and that “Renoir’s racist language stemmed from his political conservatism, staunch patriotism, and fear of anarchism.” Having presented these observations as somehow exculpatory—I don’t see why they are—she goes on to discuss Renoir’s friendship and involvement with the dealer Alexandre Bernheim and his sons, Josse and Gaston. She believes it is “unlikely” that he would have exhibited with them if he were anti-Semitic. She cites “a racist comment,” but argues that “his prejudice did not extend to hatred.” And she somehow deduces from this that Renoir “was not an anti-Semite.”

The truth—messier, less comfortable, but altogether human—probably lies somewhere between the two. White seems vexed that Renoir’s extraordinary personal warmth and kindness couldn’t keep him from embracing a violent public prejudice. But it is by no means unusual for a person to assume public or political positions that are not entirely consistent with private feelings or conduct. Although we cannot overlook Renoir’s anti-Dreyfus politics and the harsh remarks that he sometimes made about the Jews with whom he did business, we must also acknowledge the extraordinary delicacy of feeling that he brought to his portraits of Jewish friends and associates.

White’s tendency to see everything in black and white is fatal when it comes to understanding human motives and passions. It’s equally dangerous when grappling with the achievement of an artist who was simultaneously as radical and conservative as Renoir. When she attempts to describe his shifting stylistic complexities, she falls back on flatfooted labels such as “Realistic Impressionism,” “Classical Impressionism,” and “Ingrist Impressionist.” These sound like captions in a Powerpoint presentation; they turn stylistic intricacies into a mix-or-match game.

As a distinguished scholar of nineteenth-century French art history, White is surely aware that for more than a generation now the social, economic, and political crosscurrents of nineteenth-century French art and culture have been the subject of many important studies and much heated discussion and debate. There is no way to tell the story of Renoir’s life in art without taking a deep dive into the tangled, overlapping, forever morphing relationship between the official and the unofficial art communities of his time. There is no way to comprehend Renoir, who was both a romantic and a classicist, without knowing that the rival claims of Delacroix and the romantics and Ingres and the classicists were turning out, by the end of the nineteenth century, to have “forged the same links in the chain.” That was how Matisse put it; he was a great admirer of Renoir and indeed visited toward the end of the older man’s life.

White may believe, rather conventionally, that a biographer should stick to the life story and leave to others an expansive study of the painter’s social and artistic milieu or an extensive critical assessment of the work. Whatever her reasons, she fails to impress upon her readers the radical nature of Impressionism, to which Renoir was deeply committed in the years around 1870. And once she has failed to adequately explain the Impressionist rejection of substance in favor of sensation—which obsessed Renoir’s great friends Monet and Cézanne to the ends of their lives—she is hard put to grapple with the yearning for solidity that took hold of Renoir in the 1870s and led him to embrace for a time the classicism of Ingres, by some measures the arch-conservative of nineteenth-century French art.

Jean Renoir, in his book about his father, remembers him remarking, “When you are young, you think everything is going to slip through your fingers. You run, and you miss the train. As you grow older, you learn that you have time, and that you can catch the next train.” That strikes me as a rather lovely way to describe Renoir’s gradual move from a kinetic painterly style to a volumetric painterly style. So deep was his yearning for sculptural substance that toward the end of his life he actually began to make sculpture. These portraits and nudes, which were executed by a young sculptor working under Renoir’s close supervision at a time when the artist was almost completely paralyzed, are among the miracles of early-twentieth-century art. Here an artist so often associated with catching life on the quick demonstrates a mastery of sculptural weight and mass every bit the equal of Rodin’s.

Renoir was by no means the only avant-garde artist who sometimes chose to turn his attention to the art of the past. I would argue that the backward glance is almost always a critical element in the avant-garde enterprise. The avant-garde rejection of current assumptions, standards, and prejudices is driven by a search for root causes and primary sources—by a desire to reject the present not in favor of some amorphous future but in favor of first principles. The avant-garde interest in childhood, in the unconscious, in the popular arts, in the art of Africa and the South Seas, of pre-Classical Greece and Romanesque Europe—all of these were efforts to recapture the primary nature of experience.

So it was with Renoir. White writes of his conservatism and his disdain for many aspects of the modern world. But it is only when one turns to his son Jean’s book that one really begins to feel how deep and abiding what I would call Renoir’s avant-garde conservatism was. “I hate the metric system,” the painter told his son at one point, “which is a creation of the mind, because it has replaced measurements based on the human body—the thumb, the foot, an arm’s length and the league.” Renoir commented that he liked “furniture made by the village carpenter; the days when every workman could use his imagination.” That suspicion about the dangers of industrialization and standardization goes back to Ruskin, William Morris, and the Arts and Crafts Movement, and is of course very much part of the genealogy of modernism.

“All men who have created something of value,” Renoir told his son, “did so not as inventors, but as catalyzers of existing forces as yet unknown to the common run of mortals.” It was this belief that contemporary artists had to tap into some timeless source of imaginative energy that endeared Renoir to considerably younger and by many people’s estimates far more radical artists, including Bonnard, Matisse, and Picasso. They saw in the monumental figures and nudes of his later years, which he composed of tiny, overlapping strokes of jewel-like, practically translucent color, a return to the foundations of Western art. Renoir rejected the meticulously plotted compositional strategies of the Renaissance in favor of the immediacy of the figures, still lifes, and landscapes that Roman artists had painted hundred of years earlier on the walls of homes in Herculaneum and Pompeii.

Even rather sophisticated museumgoers are often startled to discover that artists as adventuresome as Matisse and Picasso were drawn to Renoir’s monumental nudes. They admired his ability to fuse the hedonistic color of Impressionism with a solidity of form that felt primordial. Renoir recaptured the spirit of Greek sculpture before the classical period, when there was still something unfamiliar and maybe even a little shocking about the unabashed physical power of the human form. The immense neoclassical figures that Picasso drew and painted during and after World War I are, among many other things, an extended series of homages to the work of Renoir’s old age.

Renoir’s influence on several younger generations was the subject of an important exhibition, “Renoir in the Twentieth Century,” which was seen in Paris, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles in 2009–2010. My sense is that that exhibition didn’t change many minds, even though it included some of the most ravishing achievements of Renoir’s final phase, among them The Great Bathers (1918–1919) and The Concert (1918–1919), in which the unearthly richness of the color suggests crushed rubies, emeralds, garnets, sapphires, and diamonds. I can’t help feeling that “Renoir in the Twentieth Century,” like so many other Renoir exhibitions of recent years, was motivated less by scholarly or critical enthusiasm than by an administrative belief that Renoir’s name will bring in the crowds, as it does.

What gets lost in the oceans of publicity that accompany these exhibitions is the artist’s imaginative courage. Renoir was a man who perpetually doubted what he did. In 1884 he wrote to a friend, “I am beginning a little late in life to know how to wait, having made enough fiascos.” He was capable of mocking himself, observing at one point that “it’s certainly the most comical thing in the world that I am depicted as a revolutionary, because I am the worst old fogey there is among the painters.” In 1907, after a lifetime of painting, he said, “I am continuing to search for the secrets of the masters; it’s a sweet folly in which I am not alone.” To his son Jean he spoke of being a cork bobbing along in a stream, going wherever the current led him.

The great irony of Renoir’s reputation is that the risks that he took have so often been mistaken for middlebrow compromises and capitulations. Those who believe that his work is little more than corn—and sometimes, of course, it is—have failed to grasp the extent to which he reclaimed the essential human sweetness, delicacy, tenderness, and voluptuousness that nineteenth-century commerce was rapidly turning into kitsch. The avant-garde had many responses to the sentimentality of so much commercial art. They ranged from the primitivism of Gauguin and the Expressionists, with its wholesale rejection of modernity, to the work of the Suprematists and the Futurists, who believed that being modern necessitated a rejection of the old emotions.

For Renoir—who abhorred the routinized, rationalized nature of modern civilization—the only solution was to reaffirm the most immediate sensations, but reimagined as aspects of eternity. Renoir told his son Jean that “the dream of his whole life” had been “to create riches with modest means.” Perhaps the problem that so many people continue to have with Renoir’s paintings is that they are simultaneously too rich and too modest. We want things one way or another. We can’t keep two thoughts in our minds at the same time.

This Issue

December 21, 2017

Lies

Kick Against the Pricks

The Man from Red Vienna