In May 1941, Winston Churchill gave orders for a cinema to be installed at Chequers. This house in Buckinghamshire, built under Queen Elizabeth I but heavily gothicized under Queen Victoria, and which a benefactor had presented to the nation in 1917 as a country residence for the prime minister, had acquired a new importance as it was forty miles from Downing Street and the Blitz. There Churchill would retreat on weekends to brood about the war undisturbed by bombs, and to relax as best he could.

He had always enjoyed drama, on stage and then on screen, and he saw public life as a kind of dramatic performance, with himself in the lead: Jonathan Rose gets this right in the subtitle of his valuable book The Literary Churchill: Author, Reader, Actor (2014). Churchill’s hugely prolific literary output (from around 1930 onward much assisted by researchers and ghostwriters) had included film scripts and one novel—the swashbuckling if not quite bodice-ripping 1900 Savrola (“a tale of the revolution in Laurania”), of which he later endearingly said that “I have consistently urged my friends to abstain from reading it.”

In 1929 he visited Hollywood—where he befriended Charlie Chaplin, among others—and between 1934 and 1936 he was paid the very large fee of £10,000 by the Hungarian-born producer Alexander Korda to write two screenplays. One was about the Great War and the other about the life of George V. In the former, an American fighter pilot who has pretended to be a Canadian to join the Royal Flying Corps hears the news that his country has entered the war and says, “Oh! I’m so glad! I was brought up on George Washington, who never told a lie.”

This might have been an uncanny premonition of that remarkable phenomenon of our time, the American cult of Churchill. It is expressed through presidential invocations, warships and high schools named after him, statues from New Orleans to Kansas City, dinners in Washington and exhibitions in New York, and endless books, movies, and television series. This cult has had consequences that are serious, and too often lamentable.

Maybe it was as well that neither of Churchill’s two screenplays was filmed, but Korda would continue to play an important if little-known part in Churchill’s financial life. During World War II, enormous sums were paid, in strictly private deals, for the film rights to Churchill’s biography of his ancestor the first Duke of Marlborough and his History of the English-Speaking Peoples, which would not be published for years to come. Again neither movie was made, but Korda became Sir Alexander as an expression of gratitude.

At Chequers, Churchill and his colleagues would watch the latest films and newsreels showing the progress of the war. George Orwell said that Churchill had “a real if not very discriminating feeling for literature,” and the same could be said of his cinematic tastes. He detested Citizen Kane, but then he may have been aware that it was to some degree based on William Randolph Hearst, with whom and with whose newspapers he had established a lucrative relationship after he stayed with Hearst at San Simeon in California, the model for Kane’s Xanadu. On the other hand, he loved Laurence Olivier’s film of Henry V, a Churchillian vision of war-as-epic released the same year that another army crossed from England to Normandy.

It was the war years that saw the first depictions of Churchill onscreen. The very first may have been Ohm Krüger, a 1941 German agitprop film about the Boer War (winner of the best foreign movie award at that year’s Venice Film Festival—and how many ardent cineastes remember that?), with a whisky-sodden Queen Victoria and a brutal commandant of a concentration camp—a phrase used by the Spanish in Cuba shortly before the Boer War and borrowed by the British in South Africa—who butchers women. He is unnamed but bears a striking resemblance to Churchill, who had been a war correspondent there and was imprisoned by the Boers.

Scarcely less of a curiosity is Mission to Moscow, directed by Michael Curtiz in 1943, and based on the fatuous memoirs of Joseph Davies, the American ambassador to Moscow. In the film, the Moscow Trials are portrayed as a judicially proper punishment of fifth columnists and traitors. It was bitterly denounced by the anti-Stalinist left, including Edmund Wilson and Dwight Macdonald, although Churchill called Stalin’s purges “merciless but perhaps not needless.” On his way to Moscow Davies meets Churchill, played by Dudley Field Malone, an American lawyer and politician with a sideline as a character actor, who was thought to bear a close resemblance to the prime minister.

Advertisement

Slowly, steadily, increasingly, movies and television programs about Churchill began to multiply, until a trickle became a stream and then a torrent. This past year has seen at least two new biopics: Churchill, set in May 1944 before D-Day, and Darkest Hour, set in May 1940 before the fall of France. There’s also the hugely successful Dunkirk. Churchill doesn’t appear in that noisy film, but at the end a soldier brought back from France picks up a newspaper and reads, “We shall fight on the beaches…”

In the outpouring of war movies after 1945 there were sometimes brief appearances by Churchill. But the great breakthrough in Churchilliana, and the first real burgeoning of the Churchill cult, began around fifteen years after the war. Shown over 1960 and 1961, the twenty-seven-part The Valiant Years was based on Churchill’s The Second World War. One of the first important documentaries broadcast on American television, it was directed by Anthony Bushell and John Schlesinger and seen by huge numbers of viewers. The producer, Jack Le Vien, originally hoped that the narrator would be Prince Philip, but he had to make do with Gary Merrill, while Richard Burton spoke Churchill’s words.

Given the dates it was shown, it’s possible that The Valiant Years had a part in John Kennedy’s photo-finish defeat of Richard Nixon in November 1960. Kennedy was the first president to invoke Churchill, as did Rose Kennedy, reminding voters that her boy Jack had been in London just before the war, and had written the Churchillian Why England Slept as his senior thesis at Harvard. (She understandably didn’t remind them that her husband, Joseph, ambassador to the Court of St James’s and surely FDR’s most eccentric appointment, was a corrupt, anti-Semitic appeaser who thought that England was finished in 1940.)

In 1964 came The Finest Hours, a documentary narrated by Orson Welles, with Churchill’s words spoken by Patrick Wymark. That was the year before Churchill’s death. Eight years later came the first biopic, Young Winston, based on My Early Life, Churchill’s most enjoyable book. Produced by Carl Foreman, a leftist fugitive from Hollywood, it was directed by Richard Attenborough with a stellar cast: Robert Shaw, Anne Bancroft, John Mills, Anthony Hopkins, and Jack Hawkins. The title role was played by a then unknown, Simon Ward; Pippa Steel was the girlish Clementine Hozier, whom Churchill married in 1908.

One small part in Young Winston was taken by Robert Hardy, as the headmaster of Harrow. Hardy had actually met Churchill twice—first when he was introduced to him as a boy by a family friend, Dr. William Temple, the archbishop of York, later of Canterbury; and then in 1953 when he was playing in Hamlet at the Old Vic with Richard Burton in the title role. After the play, Churchill went backstage and entered Burton’s dressing room with the words, “My Lord Hamlet, may I use your facilities?,” which became one small part of the great corpus of Churchillian anecdotage.

Little can the two actors at the Old Vic have guessed that they would one day impersonate their backstage visitor. After The Valiant Years, Burton played Churchill in the 1974 American television biopic The Gathering Storm. At the time, he incautiously told an American reporter that “to play Churchill is to hate him,” and recalled the loathing felt for him in the South Wales of his boyhood as an enemy of the working class and a man who had sent troops to Tonypandy during a mining dispute in 1910. Burton was not asked to play Churchill again.

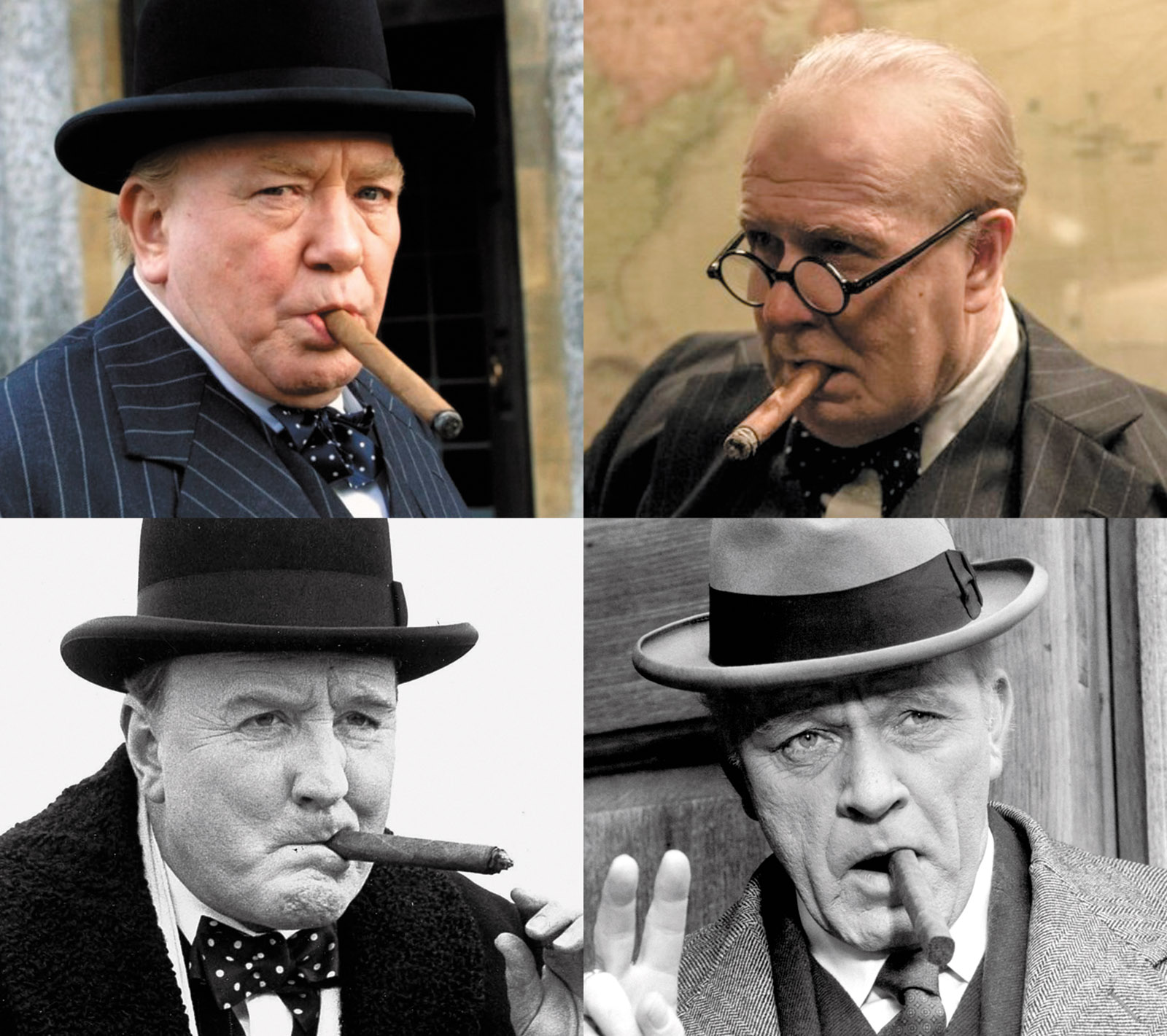

But Hardy almost cornered the market. He began in 1981 with Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years, an eight-part television dramadoc with Siân Phillips as Clementine, and never looked back. By the time he died last summer at ninety-one, Hardy had almost lost count of his Churchills, from supporting appearances in the television movies The Woman He Loved and Bomber Harris to a last hurrah in Churchill: 100 Days That Saved Britain in 2015. In between there was Winnie, by all accounts a simply excruciating musical that closed soon after it opened, and even a French play, Celui qui a Dit “NON.” Hardy won a BAFTA, the British Oscar, for The Wilderness Years, in which he set the tone for Churchill as larger-than-life bulldog, with the scowls and the jowls, the hats and the cigars, the mannerisms and the lisping speech that could make Churchill sound drunk even when he was sober.

Since then one actor after another has taken on the part, even though, as the late A.A. Gill rightly said, Churchill was an “iceberg for titanic thespian aspirations.” Maybe the best was Albert Finney in The Gathering Storm, a 2002 BBC–HBO biopic with Vanessa Redgrave, who was so good that Mary Soames, the Churchills’ youngest and last surviving child, exclaimed while watching, “It’s Mama!” Most recently, in what must be an incomplete catalog, were two better-than-usual television Churchills, Michael Gambon and John Lithgow. In Churchill’s Secret (2016) Gambon wisely eschewed the usual shtick—Churchill defiant, Churchill triumphant—and gave us Churchill in unhappy decline. The “secret” of the title was the severe stroke that incapacitated the prime minister for weeks in the summer of 1953, while the country was run by a handful of senior ministers. The public was kept completely unaware of this by a conspiracy among the press lords, principally Churchill’s friends Beaverbrook and Camrose.

Advertisement

In World War II: When Lions Roared (1994), set at the Tehran conference in 1943, Bob Hoskins was an against-type Churchill. Michael Caine was Stalin, and Roosevelt was played by Lithgow, who has since switched roles: in the very successful, although sometimes historically misleading, Netflix drama The Crown, to quote Gill again, “Lithgow’s Churchill is a marvellously monstrous rendition of the old sot.” It was surely significant that a program ostensibly about the queen and her family should have digressed into such pure Churchillian territory as his meeting with Graham Sutherland, who was painting his portrait.

This year’s cinematic incarnations aren’t bad by those variable standards, although it seems that Clementine is as easy a part to get right as Winston is to get wrong. There have been few bad performances of that highly intelligent, highly strung, intimidating lady. Harriet Walter was good in The Crown, and Miranda Richardson in Churchill and Kristin Scott Thomas in Darkest Hour both shine. As to Churchill, Brian Cox is more than adequate in the former, and Gary Oldman surprisingly good in the latter, another improbable piece of casting for an actor whose previous roles have included Sid Vicious and Lee Harvey Oswald.

Both these movies are heroic fantasies. As Churchill opens, shortly before D-Day, our hero walks by the seashore and sees the water running blood red. He is, we are to suppose, obsessed by the horrors of the Gallipoli landings twenty-nine years earlier—“so many young men, so much waste”—and consumed by dread of another futile slaughter on the beaches of Normandy. He attends an unlikely open-air conference with Eisenhower, Montgomery, and King George VI, where he pleads for the landings—the greatest of their kind in history and years in the planning—to be canceled. Not surprisingly he’s politely ignored and goes home to sulk.

To add a bizarre touch, Churchill insists, before leaving home, that he must wear formal dress with knee breeches to meet the sovereign. Later on there are some more droll moments, as when Churchill tells a minion to find out from General Sir Harold Alexander whether he has taken Rome yet, something that the Allied commander in Italy would quite likely have communicated quickly to the prime minister when it happened.

These movies tend to have a tenuous basis in fact. In the case of Churchill, it was certainly true that Churchill dragged his feet as long as he could over a cross-channel invasion, which was the one way that the Western Allies could make a serious contribution to the defeat of Germany. Even as D-Day approached he was deeply apprehensive, and told Clementine that he foresaw terrible casualties, many more than there were in the event.

But the idea that he tried to call off the landing at the last moment is silly. And even more misleading is any idea that he was guilt-ridden about Gallipoli. He knew that lamentable episode clouded his reputation and resented that, since he continued to think, against all evidence, that it was a brilliant enterprise undone by incompetent execution and sheer misfortune. What makes Churchill more curious is that it was written by Alex von Tunzelmann, who has published Reel History (2015), a collection of essays about how the movies travesty historical truth.

Although Darkest Hour has already garnered critical praise and may prove a greater success, it is in some ways a more dangerous warping of the truth. After an absurdly unlifelike scene in the House of Commons (which neither large nor small screen ever gets right), with the whole House seemingly wanting Neville Chamberlain to resign, Churchill is appointed by King George VI with the odd words, “It is my duty to invite you to take up the position of prime minister of this United Kingdom,” rather than Churchill’s plausible and amusing account of what actually happened: the king playfully asked Churchill if he knew why he had been summoned to the palace, to which Churchill replied, “Sir, I simply couldn’t imagine why.”

As the calamity in France unfolds, the evil Chamberlain and Lord Halifax (Ronald Pickup and Stephen Dillane) still conspire against him. These portrayals are coarse caricatures, outrageous in the case of Halifax, who was the least enthusiastic of the appeasers, although ten years earlier as viceroy of India he had certainly tried to appease Gandhi—to the rage of Churchill, who called Gandhi “a half-naked fakir” unfit to rule India with its “primitive” inhabitants.

In one absurd scene, the two continue their wicked plot over dinner, wearing white tie and sloshing brandy. In another, the king visits Churchill late at night to promise him his support. Almost by convention now, there is a pretty young woman (Lily James) working for Churchill whom he bullies but then befriends. At one point, she tells him that he’s making his V-sign the wrong way, palm backward, which means “Up your bum,” at which they dissolve into giggles.

All of that is surpassed by a scene in which Churchill leaps out of his car and into the Underground. In the train, he finds a group of stout-hearted Londoners full of the Dunkirk spirit. When he quotes Macaulay’s “Horatius at the Bridge,” his line is finished by a black passenger. Soon our hero is cheered in the Commons by MPs on all sides. In fact, the Tory benches were sullenly subdued through his first famous speeches in May and June, and only cheered him when he announced the perfidious sinking of the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir.

Do these fantastical entertainments matter? And what do they say about Churchill—or about us? There is a standard defense that such movies are dramas, not documentaries, but that’s disingenuous. For every person who has read serious, detached books about Churchill and his times, there will be thousands whose knowledge of him comes from cinema and television. And by now the encrustations of mythologizing and hero worship have gone beyond a point where they can be easily corrected. The line at the end of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence—“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”—is the guiding principle for depictions of Churchill in popular culture.

Almost more dangerous than obvious hokum are the dramadocs. The Wilderness Years that launched Hardy on his long Churchillian career was cowritten by Martin Gilbert, then still engaged in his monumental, informative, but uncritical official biography, and the program gave the authorized Churchillian version of the 1930s: Churchill the prophet unheard, the giant struggling against the pygmies of appeasement. Orwell’s life was changed by the Spanish civil war, not just from fighting in it but from reading so many lies about it that he wondered whether a true account of contemporary events could ever be written. One sometimes wonders whether a true account of the 1930s will ever penetrate public consciousness, against the version Churchill so successfully if spuriously imposed of his lonely voice against the craven appeasers who failed to enlist other nations and the German generals to thwart Hitler’s aggression. Robert Harris’s new novel Munich, published in America in January and already a British best seller, is most unusual in giving a sympathetic portrait of Chamberlain.

It’s true that senior British politicians wavered at the time of Dunkirk, when it seemed for some days that most of the British army would be lost. Even Churchill for a moment talked of possible concessions to Hitler that might lead to a negotiated peace. But why is that surprising? England could see no help at hand, and not much objective reason for hope. Americans who lap up Dunkirk and Darkest Hour might remember that their own compatriots were resolutely united in their determination to have nothing to do with resisting Hitler, not only in September 1939 and June 1940 but until December 1941, when Hitler left them no choice by declaring war on the United States.

It matters to remember such things, because Churchill is still all too much with us. The Brexit referendum campaign was one of the most unpleasant public events I can remember, distinguished by bombast and downright mendacity on both sides—and with Churchill continually invoked, also by both sides. Sir Nicholas Soames MP, Churchill’s grandson, and the present Duke of Wellington both claimed that their illustrious forebears—the great Marlborough, the Iron Duke, and Sir Winston himself—would have supported Remain. But Churchill’s image constantly appeared on the front pages of the Sun and the Daily Mail, supposedly urging Leave.

On the American side of the Atlantic, the uncontrollable Churchill cult has had its own dark consequences. Reverence for Churchill and disdain for Chamberlain stiffened President Lyndon Johnson’s resolution to send more troops to Vietnam, as he said himself. President Ronald Reagan paraphrased Churchill in his first inaugural address to justify his economic policies. And President George Bush the Younger never stopped quoting Churchill, above all when urging the invasion of Iraq. In somewhat optimistic words, Joe Wright, the director of Darkest Hour, sees his movie as a rebuke to Donald Trump: “Churchill resisted when it mattered most, and as I travel around America I am really impressed and optimistic at the level of resistance happening in the US at the moment.”

However that might be, Wright must know what effects his film and Dunkirk are having in England at present. Max Hastings recently pointed out in these pages that Dunkirk, doubtless without its makers’ intending it, is taken by some as a Brexit movie, as we plucky islanders once more shake the dust of Europe from our feet.* As if to make that point, a headline in the Daily Telegraph spelled it out: “When it comes to Brexit, we need our Dunkirk spirit back.”

But could “our Dunkirk spirit,” however splendid it was at the time, have been our undoing since? More than a century ago, Giovanni Giolitti, the Italian prime minister, claimed that “beautiful national legends” help sustain a country. He should have added that they can also do great harm. For the English, “1940” is now the greatest of such legends: Dunkirk and “Very well, alone!,” the Battle of Britain and “the few,” the Blitz and “London can take it,” and Churchill’s speeches echoing all the while.

In 1940, Churchill said that “if we open a quarrel between the past and the present, we shall find that we have lost the future,” which is one way of putting it. Another way is Orwell’s in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.” Churchill—real or imagined—now controls the past, the present, and, alas, the future, maybe with bleaker consequences than we can yet know.

This Issue

January 18, 2018

Damage Bigly

Divine Lust

This Land Is Our Land

-

*

Max Hastings, “Splendid Isolation,” The New York Review, October 12, 2017. ↩