In a career lasting more than seventy years Michelangelo reigned supreme in every art: sculpture, painting, architecture, drawing, poetry. So absolute was his mastery, and so Olympian were his creations, that he seemed more than mortal to his contemporaries. They called him “divine,” said his works were the most sublime ever made, even greater than those of antiquity, and used a new term, terribilità, to describe the awesome majesty of his art.

His titanic creativity can never be fully conveyed within the confines of a museum exhibition. His greatest masterpieces, such as the Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome and the New Sacristy in San Lorenzo in Florence, must be experienced at their sites, and even the works that can be moved are deemed so precious that they are rarely loaned; some never are. While there have been exhibitions on parts of Michelangelo’s life and oeuvre, few museums have tried to outline the broad sweep of his inexhaustible artistry.

Yet that is exactly what “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art sets out to accomplish. It covers the entire career of the artist, from his first extant drawings made while he was a teenager to works created shortly before his death at eighty-eight in 1564. The heart of the exhibition is a selection of 133 of his drawings, the largest group of them ever displayed at one time. It also includes his earliest painting, one late architectural model, and three of his sculptures, from very different points in his life. Michelangelo’s activity as a poet is included as well, with two manuscripts in his own hand of his very moving sonnets; these add significantly to our understanding of the artist. Brilliantly curated by Carmen Bambach, a scholar of drawings at the Metropolitan, and beautifully presented by the museum’s exhibition and lighting designers, this is likely the finest show on the artist any of us will ever see.

The material is arranged mainly in chronological order, but this is meant to do more than merely tell the familiar story of Michelangelo’s career. His fame as the greatest artist of all time both trapped and liberated him. For almost his entire life he was compelled by rulers to slave away on their pet projects, yet he was more free than anyone before him to make art in any style he willed, and to devise new imagery wholly of his own choosing. His works have a deeply personal character that was unprecedented in the history of art. As Bambach writes, “his drawings, like his sculptures, often exude a certain autobiographical intensity of feeling.” Without ever being tendentious, this grouping of works allows the viewer to begin to see the passion, melancholy, fear, and frustration that drove the artist.

The exhibition opens with a long room dedicated to Michelangelo’s youth and brief training in Florence with the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio and the sculptor Bertoldo. Nearly all of his few extant drawings from this time are on view. Mostly copies after frescoes by Giotto and Masaccio, these sheets reveal the penetrating study of Florentine masters that lay at the foundation of his art, and also his precocious confidence in his own sense of form. He not only imitates but also corrects his celebrated predecessors. For instance, his Study after Saint Peter by Masaccio, drawn perhaps around 1490, looks more like a powerful sculpture than like the painting he copied it from. The saint’s robes billow with stately grace, and his head has the sharp edges and rectangular shape of a block of stone; it even bears a strong resemblance to Michelangelo’s marble portrait of Brutus, made many decades later, which is exhibited near the end of the show. Despite the drawing’s monumentality, there is nothing stiff about it; the outlines of the figure are fluid and calligraphic. So great is the vitality of this youthful sheet that by comparison the drawings of his teacher Ghirlandaio shown nearby look scratchy and flat.

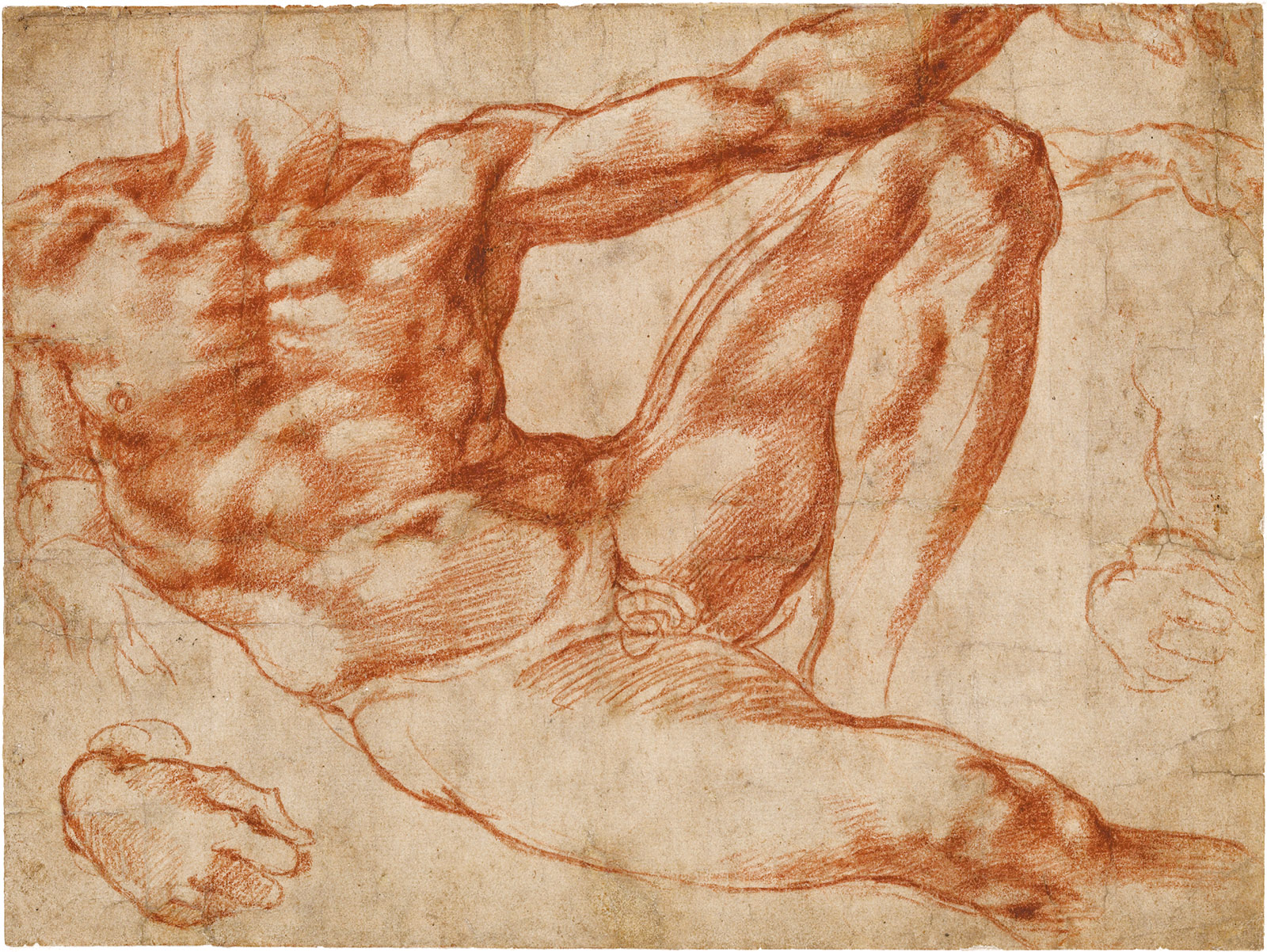

When you enter the second room the exhibition really takes off. The centerpiece of this section is a drawing, but remarkably one that was destroyed more than five hundred years ago, soon after its making. This is Michelangelo’s giant cartoon for his fresco The Battle of Cascina, from around 1506, which he intended to paint on a wall of the Great Council Hall in the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence, but was unable to execute owing to demands from other patrons. Although the cartoon does not survive, many of his preparatory studies for it do, and the exhibition brings together a selection of them plus an early painted copy. These show nude or nearly naked men, rendered with great anatomical accuracy and portrayed in taut and twisting poses.

Advertisement

One particularly beautiful image from this group is a Study of the Torso of a Male Nude Seen from the Back. Here Michelangelo demonstrates absolute control of every element of draftsmanship. The depiction of the musculature is of astonishing subtlety, and the fall of lights and darks across the skin is so finely graded that the entire figure seems to throb with life. Remarkable too is the undulating line that runs around the contours of the body. This varies continuously in thickness and tone, adding significantly to the sense of quickening vitality. Each of these effects was new, and their combination so stunned other painters, including Raphael, Pontormo, and Andrea del Sarto, that they obsessively studied and copied the cartoon. In the words of Benvenuto Cellini, Michelangelo’s majestic drawing became “the school of the world.”

In his great biography of Michelangelo, first published in 1893 and never surpassed, John Addington Symonds calls the Battle of Cascina cartoon “the central point” and the “watershed” of the artist’s career. It was the first work in which Michelangelo broke free of all convention and dedicated himself to the subject that was to occupy his imagination for the rest of his life: the male nude. As Vasari remarked, “the intention of this extraordinary man has been to refuse to paint anything but the human body…[and] the play of the passions and contentments of the soul.” It is hard for us to conceive how revolutionary a choice of subject matter this was. To be sure, only a few years before, Luca Signorelli had filled his frescoes in the cathedral of Orvieto with naked bodies, but those figures seem to be made of dirty and mortal flesh, while Michelangelo’s exult in triumphant and noble beauty.

As he worked on the cartoon, the artist began planning other major paintings and sculptures, principally for Pope Julius II. The first was the pontiff’s tomb, which Michelangelo originally designed to be a colossal monument, ringed with as many as forty-seven massive marble sculptures. This project was to bedevil him for forty years, and finally end with a wretched wall tomb in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, best known for the artist’s statue of Moses at its center. As the drawings shown here demonstrate, from the start the commission inspired Michelangelo perhaps prophetically to imagine statues of heroic men, bound and struggling for freedom.

Another commission of Julius II was the Sistine Chapel ceiling, which the artist completed in 1512. At the Metropolitan, the studies for the painting appear out of historical sequence; they are grouped together in a gallery two rooms away from where they would appear according to a more strict chronology. This disrupts the crucial continuity of these drawings with those of The Battle of Cascina and Julius’s tomb. Seemingly this was done so these sheets could be shown below a large glowing photograph of the Sistine fresco, hung from the ceiling of the museum. At first glance this brightly illuminated picture may seem distracting, but it allows the spectator to understand the place of the sketched figures in relation to their intended location in the overall scheme, and to grasp that the sublime finished whole was the result of countless preparatory studies of every detail, which Michelangelo drew with obsessive abandon.

The arc of the artist’s life changed significantly following this zenith. In the remaining fifty years of his career, Michelangelo never completed another large-scale work, with the exception of the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, the frescoes for the Pauline Chapel in the Vatican, and the greatly reduced tomb for Julius II. This failure was partly the result of political circumstance and the competing aims of his domineering patrons, and it left him with a sense of bitter frustration, even as his renown grew.

Correspondingly, the works on view in the exhibition that follow the completion of the Sistine ceiling change dramatically in mood, subject, and intended audience. Whereas previously Michelangelo had concentrated on creating sculptures and paintings of heroic figures for public display, he now often composed drawings full of private meaning and meant for his own satisfaction and that of a tight circle of close associates. Two galleries of the exhibition are given over to these images from the 1520s and 1530s, and entering this section is like crossing into some mysterious domain of dream and fantasy.

The first of these rooms features in one corner drawings Michelangelo made as gifts for friends, and in the opposite corner are studies on themes of birth, death, and resurrection. The most spellbinding of the latter group is an image from the Casa Buonarroti of the Madonna and Child, in which Michelangelo intentionally left the two figures in starkly different states of finish. Richly drawn in black and red chalk, brown wash, and white heightening, the arm and torso of the Child have glowing skin and exquisite roundness of form; He seems to be coming into being before our eyes. By contrast, Michelangelo drew the Madonna in trembling and wispy lines of sooty black chalk; she looks as if she is about to vanish into the air. In a poem written at the time of the drawing, Michelangelo used comparable imagery: “Man’s thoughts and words…are as…smoke to the wind.” Haunting too is the disparity of the expressions of the Madonna and Child. The baby seems utterly content as He obliviously nurses at her breast; she stares fearfully into the distance, distraught by visions of the horrific death He will one day suffer.

Advertisement

The drawings Michelangelo made for friends are also full of striking contrasts. One rapturous image portrays a young nobleman, Andrea Quaratesi, who studied with the artist. Michelangelo usually disdained lifelike portraiture, but this picture seems to be a keenly accurate record of the youth’s appearance, and the expression on his tender face is sad and sultry. Not long after this drawing was made, the artist’s friend Sebastiano del Piombo wrote Michelangelo to advise him to guard against “melancholy love that has always ruined you.” This delicate portrait is the very image of hopeless infatuation.

Nearby are other gift drawings, but of wholly different temperament. In contrast to the frankness and naturalism of the Quaratesi portrait, they are imaginary pictures of unreal heads in fantastical clothing. The most celebrated is a double-sided sheet depicting Cleopatra, but this drawing has little to do with the historical person. On one side of the sheet, a slithering snake wraps around her body and bites her breast. The long braid of the queen’s hair and the tail of the snake floating off into space seem to intertwine in a languorous and sinister dance. The drawing on the other side of the sheet is even more spectral. Here Michelangelo has given Cleopatra staring eyes and a grotesque mouth with fat lips and jutting teeth. She looks frightened and baleful, and yet has an odd resemblance to the Madonna in the Casa Buonarroti drawing.

Michelangelo made these images of Cleopatra for Tommaso del Cavaliere, a young Roman he fell in love with in 1532. Although apparently never consummated, it was a deeply passionate relationship that inspired most of the artist’s gift drawings as well as much of his poetry. Many of these sheets represent classical myths; others depict fantasy scenes of his own devising. One such sheet shows archers without bows shooting arrows at a herm, another represents babies sacrificing a deer. These are ravishingly beautiful images, but no one is sure what they are meant to convey.

The only explicitly homoerotic image Michelangelo gave Tommaso was a drawing of Jupiter in the guise of an eagle carrying Ganymede off to heaven. The original drawing is lost, but to judge from copies the bird seems to thrust his body against the boy’s buttocks as he lifts him upward. Since Tommaso was about thirty-eight years younger than the artist, one might assume that he is the youth in the drawing. Yet Michelangelo’s poetry suggests that the artist actually identified with Ganymede. He wrote in a sonnet for Tommaso, “Though lacking feathers I fly with your wings; with your mind I am always carried to heaven.”

During Michelangelo’s lifetime, close friends reported that his art was full of “Socratic love and Platonic ideas.” There is no doubt he saw his passion for Tommaso philosophically, as something that transported him from the earthly and ephemeral to the heavenly and eternal. In a madrigal, likely written for the youth, Michelangelo said, “My eyes that ever long for lovely things, my soul that seeks salvation, cannot rise to heaven unless they fix their gaze on beauty.” His friendship with Tommaso lasted until the end of his days.

In the rooms of works from the 1540s and 1550s, the desperate ache of spiritual longing intensifies. Ever an artist, Michelangelo now began to make art about his disenchantment with art. This is especially clear in one of his intensely poignant sonnets on view here. “The alluring fantasies of the world,” it begins, “have robbed from me the time allotted for contemplating God.” The poem ends, “Make me hate all that the world values, and all its beauties I honor and adore, so that before death I grasp eternal life.” Another poem, not in the exhibition, expresses his disillusionment in even more stinging words. While carving the fierce and tragic Pietà now in the Florentine Cathedral museum, Michelangelo wrote, “In great slavery, with such weariness, and with false concepts and great danger to the soul, sculpting here things divine.” Given his anxious discontent, it is perhaps no wonder he later attacked the statue with a hammer and abandoned it.

Some of the last figure drawings in the exhibition date from just a few years before Michelangelo’s death and depict the Crucifixion. Softly drawn in black chalk with weak and wavering lines, these sorrowful images look like they are made of shimmering smoke. They seem to depict an unattainable phantasm, at once eternal and impermanent, and beyond the reach of human understanding.

“Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer” aims at comprehensiveness. There are two galleries of his architectural drawings, a section on his studies for the Last Judgment, and two rooms of his drawings for works intended to be executed by his collaborators. The show concludes with three portraits of him, which is fitting as the exhibition is itself a kind of portrait, one that is both beautiful and hard to hold onto. This sense of elusiveness does not result solely from the sprawling scale of the presentation; it also arises from the art, which often seems to be distancing itself from the viewer and abounds with images of figures in flight or in ascent or turning away.

Michelangelo’s art was often driven by the desire to escape the mundane, physical, corrupt, and sinful world. He burned with intense passion for the beauty of the human body and face, but he hoped that this ardor would transport him to another realm, one of ideal form and deathless purity, above and beyond the earthly. The incarnate moved him to aspire to the uncarnate, the immortal, the eternal, the fantastical, the impossible: unbodied beauty. He felt enchained and trapped—by his work, by his patrons, by his family, by his lust for beauty, by his sinfulness, by his body, by the limits of the actual—and longed to be carried away in ecstasy and rapture.

One can see this in his taste for fantastical and dreamlike subject matter, in his rejection of naturalism for the odd and ideal, in his renunciation of his gift for creating drawings of the most convincing substantiality, and in his preference instead for drawings that, while exquisite, make the body look almost weightless and transparent, as if composed of radiant dust. And one can hear it in his poetry, in which he often laments his passion for the beguiling illusion of mortal beauty; he wishes he could truly adore God and the sacred, but cannot feel such love except by gazing on the human and earthly. Unquenchable desire and certain failure are twisted together in this hopeless pursuit. Hence the air of melancholy and sorrow that pervades so much of his art.

This Issue

January 18, 2018

Damage Bigly

This Land Is Our Land