1.

The imaginative fervor that gripped avant-garde master builders and artisans around 1900 in Vienna, the capital of the vast and culturally diverse Austro-Hungarian Empire, paralleled equally radical innovation in other creative realms, including the music of Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg, the painting of Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoschka, and the writings of Arthur Schnitzler and Sigmund Freud. Yet the singular contributions to the visual arts that the Viennese made during this epoch have never loomed large enough in general chronicles of modernism.

The constant rewriting of art history is not solely the province of critics and scholars; cultural institutions exert enormous influence on the way the past is perceived. This has been demonstrated most forcefully by the strong Francophile bias of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, whose founding director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., set out a Gallocentric narrative of modernism—a begat-begat-begat genealogy that began with Cézanne and posited Cubism as the central development of twentieth-century art. Barr’s highly selective account deeply affected received opinion for many decades. However, even some loyal supporters of MoMA have been aware of how much has been neglected because of Barr’s preferences. Among them is Ronald Lauder, the New York cosmetics heir, collector, and longtime trustee of the Modern, who served as its board chairman from 1995 to 2005 and cofounded the Neue Galerie, a privately funded museum devoted to Austrian and German modernism, in 2001.

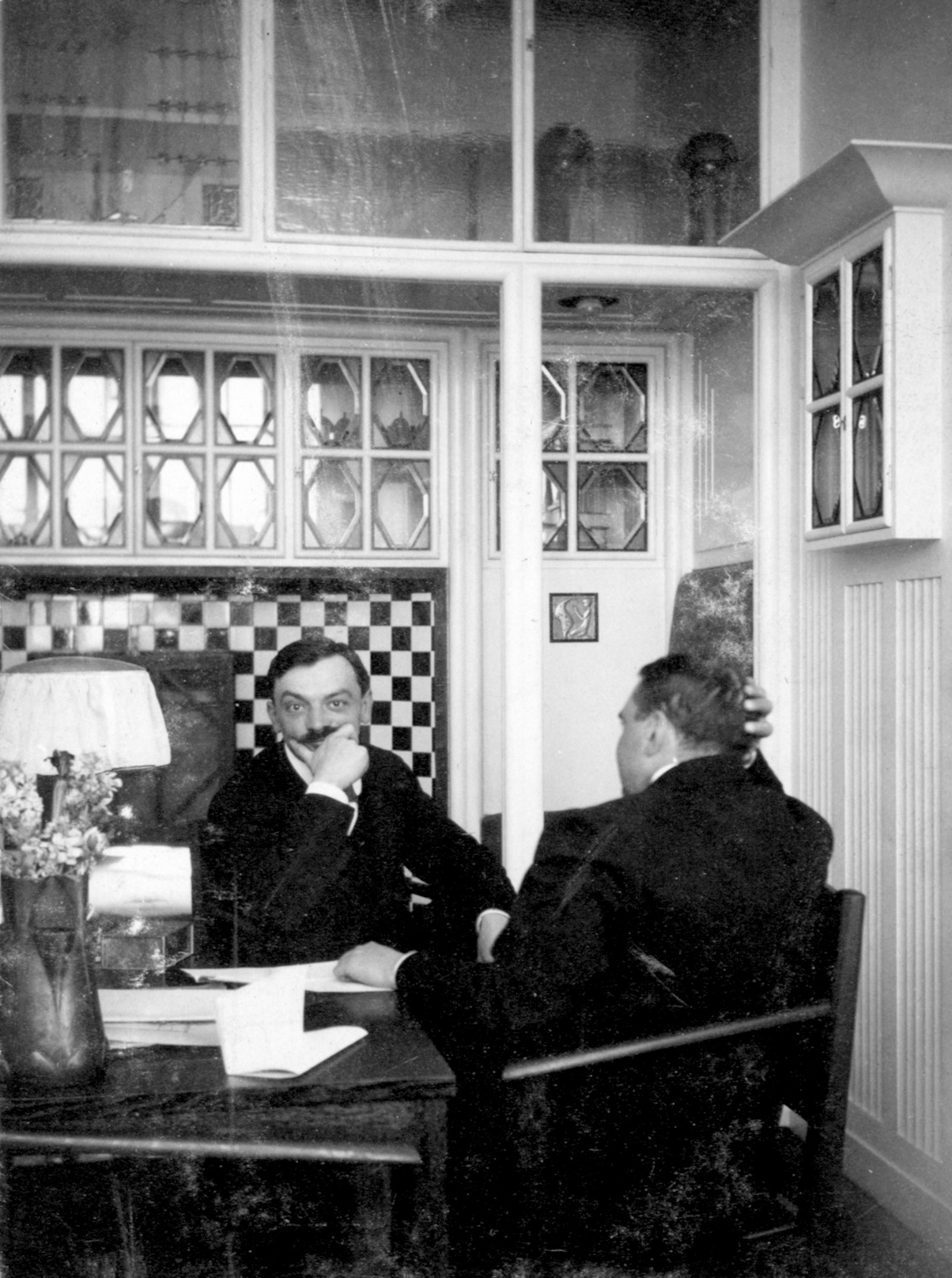

The idea for the Neue Galerie began with Serge Sabarsky, a Vienna-born, New York–based dealer in Expressionist art who in 1993 bought a Beaux-Arts mansion on Fifth Avenue and started a foundation devoted to advancing awareness of that work. After Sabarsky’s death in 1996, his friend and client Lauder took over the project and created what now seems an indispensible part of the city’s cultural life, not least because the Neue Galerie’s high standards of programming and presentation have almost single-handedly redressed the Modern’s systematic overemphasis on the School of Paris. In recent years, such hugely popular Neue Galerie exhibitions as “Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937” and “Berlin Metropolis: 1918–1933” have stood out as major curatorial accomplishments.

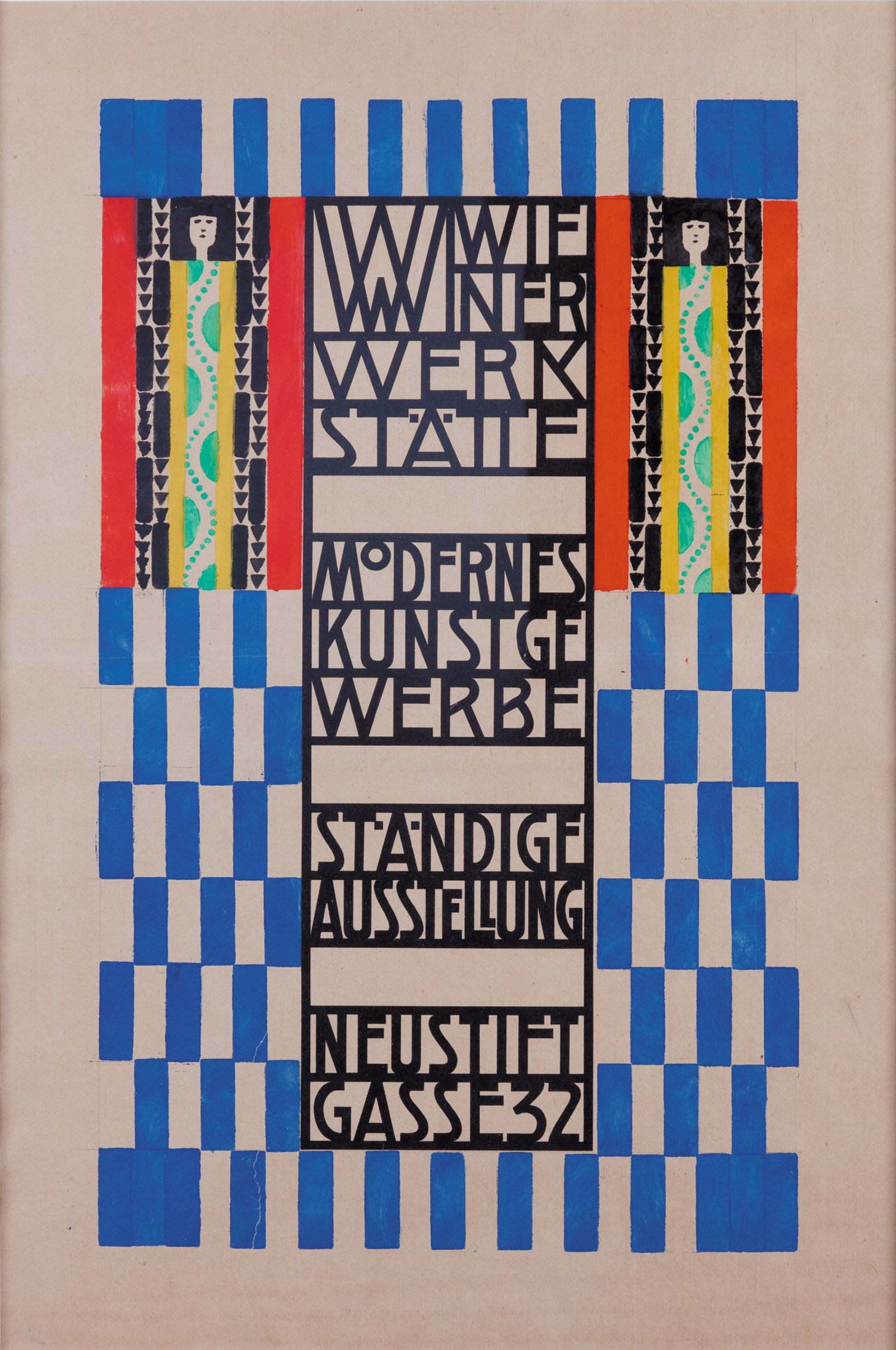

They are now followed by yet another triumph, “Wiener Werkstätte, 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty,” a comprehensive survey of the applied arts collective founded in Vienna by the architect Josef Hoffmann, the artist Koloman Moser, and the patron and collector Fritz Waerndorfer. The Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops) was a direct offshoot of the Vienna Secession, the maverick faction of avant-garde painters, sculptors, and architects who in 1897 broke away from the stultifyingly conservative Association of Austrian Artists. The new exhibition, brilliantly curated by Christian Witt-Dörring and Janis Staggs, makes a wholly convincing case for this brief efflorescence of incomparably exquisite high-style design.

On view are more than four hundred objects, including furniture, glassware, ceramics, metalwork both precious and base, jewelry, wallpaper, fabrics, graphic design, and the charming artists’ postcards with which the alliance inexpensively propagandized its ambitious agenda. The show has been stunningly installed by the Chicago architect John Vinci, whose coup de théâtre is an uncannily accurate recreation of the quirky but captivating gallery that Dagobert Peche—a Wiener Werkstätte stalwart who might be termed the organization’s id because of his untrammeled and often disruptive inventiveness, in contrast to Hoffmann, the group’s rational superego—executed within Hoffmann’s Austrian Pavilion at the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, the Paris extravaganza that gave its name to Art Deco.

Although several scholars have already convincingly proposed that the Wiener Werkstätte was the missing link between Art Nouveau and Art Deco, the Neue Galerie show and catalog confirm this notion. The eight-pound exhibition catalog harks back to the doorstop museum publications of the 1980s. Yet however opulent Witt-Dörring and Staggs’s gorgeously illustrated text might appear, it is filled with so much new research based on archival sources that it ranks as the most important reference work on the subject.

Received notions of the group and its clientele have perpetuated clichés of a decadent imperial society obliviously waltzing on the rim of a political volcano. However, the rarefied objects produced by this decorative arts consortium do seem characteristic of a pre–Great War culture of plutocratic privilege—in stark contrast to the output of the Bauhaus, which was founded the year after that devastating conflict ended. But because the Wiener Werkstätte managed to persist beyond the downfall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire for more than a decade—a period no less economically difficult for hugely diminished Austria than for its co-combatant Germany—it is incorrect to see it as a cultural hothouse flower.

Advertisement

The exhibition demonstrates how the Wiener Werkstätte went through several successive phases to survive financially. If one of its many product lines was not selling, there was no philosophical compunction against coming up with something completely different to please customers, at least within the group’s expansive stylistic parameters. This noble experiment in advanced design was nothing less than a conduit for a richly multicultural, if politically untenable, society that was coming apart at the seams bit by bit. Although there are strong underpinnings of Classicism in many of its designs—such as Hoffmann’s famous brass centerpiece, circa 1924, a fluted, footed bowl with extravagant curlicue handles that spiral wildly outward with irresistible insouciance—it is the tension between tight control and wild abandon that gives them a contradictory quality so much in tune with that time, and ours as well.

Apart from the duality of so many Wiener Werkstätte designs—which often juxtaposed urban sophistication and peasant vitality, as in Vally Wieselthier’s ceramic sculptures of women who seem equal part jaded showgirl and feckless milkmaid—the group’s broad range defies easy definition. In its more folkloristic manifestations one can detect an affinity for the Magyar side of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, while evocations of a far older empire—the Byzantine—are evident in jewelry designs such as Hoffmann’s rectilinear brooches, so densely encrusted with multicolored semiprecious stones that they recall the jewels of the empress Theodora as depicted in the Ravenna mosaics.

It now seems incredible that one company could turn out both Bertold Löffler’s anorexic stoneware bud vases (circa 1906) and then a year later Michael Powolny’s chubby ceramic putti representing the Four Seasons (high-style precursors of the kitschig Hummel figurines first made in 1935). Moser’s silver-and-niello sugar box of 1903, its cubic form further reinforced by an all-over black-and-silver-checked surface, is as severe as a Donald Judd sculpture. Conversely, Peche’s bombastic walnut writing desk of 1922 is so massive and overwrought that it could be best described as Babylonian Baroque. Yet they all bore the superimposed double-W label devised for the firm by Moser (who also came up with distinctive initialed logos for each of its participating artists), and one cannot say that any single aesthetic represents the Wiener Werkstätte, which can only be understood in all its bewildering complexity.

The group faced the same basic problem that bedeviled several of its earlier counterparts in the British Arts and Crafts movement, including the Century Guild of Artists, established by Arthur Mackmurdo in 1883; the Art Workers’ Guild, founded in 1884 by the architect William Lethaby and others; and C.R. Ashbee’s Guild and School of Handicraft (1888). Each of them was self-consciously modeled after medieval craftsmen’s guilds (though with less emphasis on exclusionary job protection, a central element of those precursors of modern labor unions). They all espoused preindustrial fabrication methods and sought to bring good design to the masses. Yet the objects they produced—even those not made from intrinsically precious materials—were so labor-intensive that they could never compete with machine-made items affordable by the working class, and thus became luxury goods for the rich.

Design reform groups that were established on conventional business models fared better financially than their utopian counterparts. William Morris’s London-based home furnishings concern, Morris & Co. (as it was renamed in 1875 to capitalize on its mastermind’s increasing renown), weathered successive changes in popular taste and lasted until 1940, forced out of business only by the Blitz. Interestingly, it was not the earnest Morris, a crusading socialist, to whom the Vienna avant-garde gravitated among British designers, but rather the Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, whose outlook was darker and more emotionally complex than the heartily straightforward ethos of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Not for nothing was Mackintosh’s Glasgow circle dubbed “The Spook School,” in response to the wraith-like quality and spiritual subtext of its decorative schemes.

Indeed, one of the Wiener Werkstätte’s signature motifs—repetitive right-angled grids in wood or metalwork—came directly from Mackintosh. His designs were extensively published in the new halftone-illustrated international applied art journals (especially The Studio, founded in London in 1893, and Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, established in Darmstadt in 1897) that allowed a rapid and reciprocal exchange of design ideas across great distances. Mackintosh also met several of his Viennese admirers in 1902 at the First International Exposition of Modern Decorative Arts in Turin, which led the Wiener Werkstätte’s greatest early benefactor, Fritz Waerndorfer, to commission a music room for his suburban Vienna villa from him. This otherworldly environment was completed in 1903, the year the Wiener Werkstätte opened for business.

2.

The economic premise of design reform groups was always shaky. The Bauhaus was a rare exception, thanks to its being a state-sponsored school (hence its official name, Staatliches Bauhaus) and thus free from the financial pressures of a commercial enterprise. In due course its numerous design patents and licensing agreements (especially the hugely popular Bauhaus wallpaper lines) brought in a steady if not enormous income that, with admirable equity, was parceled out to students who devised the product prototypes in their workshop classes.

Advertisement

The Wiener Werkstätte, in contrast, was a money pit from its inception. This has long been known, but a comprehensive account of the group’s parlous finances has never before been laid out in such disheartening detail as it is in the most important chapter of the exhibition catalog, “Economics,” by Ernst Ploil. The Wiener Werkstätte’s economic dilemma is summed up in a letter from Hoffmann to the Belgian engineer and financier Adolphe Stoclet—patron of the architect’s masterpiece, the Palais Stoclet of 1905–1911 in Brussels:

The lady [Miss Wittgenstein] wanted (for months now) two candelabra, each two meters tall, of gilded wood. Finally the drawings were finished and correct, and a cost estimate was drawn up in my absence. That alone is madness, since it is simply impossible to produce a cost estimate for an object you haven’t yet made…. Fortunately, Miss Wittgenstein came and said the estimate was too high. And at that moment I already told her that we were freed of any obligation because she did not accept the estimate and that now we will not make the candelabras at any price, because we no longer make unique objects….

“Strange,” said Miss Wittgenstein, “and we always thought you were getting extremely rich from these commissions.” And I said to her: “You can best see just how much such commissions can enrich us (she wanted to pay eight thousand crowns [equal to more than $100,000 today] for the candelabras) from the fact that now we simply no longer accept such commissions.”

Miss Wittgenstein (a sister of Ludwig’s, though it’s not clear which) was a member of a steel-manufacturing dynasty that had converted from Judaism to Protestantism and was the second richest family in Austria, after the Rothschilds. As Witt-Dörring explains in the catalog:

The Werkstätte was supported by a small group of artists and primarily Jewish wealthy families that were relatives or friends or were connected by economic interests and backed the project of Vienna’s artistic springtime with their commissions. The members of the Jewish families had generally assimilated into Vienna’s Christian culture in the second generation after Austria-Hungary’s Jewish population obtained full civil rights from around 1860. Their desire to integrate fit well with…[the] search for a modern Austrian style…which gained acceptance in the international market as the “Viennese style,” [and] offered the assimilated Jewish population the potential of a feeling of belonging that was not defined in terms of nation.

Another mainstay of the Wiener Werskstätte was the Primavesi family, descended from Italian Jewish bankers who during the eighteenth century emigrated from Lombardy to Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic but ruled by the Austrian Empire from 1809 to 1918). Hoffmann designed two large residential schemes for members of that clan. He carried out a complete interior remodeling of the baronial Primavesi Country House, near the Moravian town of Winkelsdorf (1913–1914), for the entrepreneur and parliament member Otto Primavesi. And for Otto’s younger cousin-and-brother-in-law, the banker and industrialist Robert Primavesi, and his wife, Josefine Skywa, he created the neo-Classical Villa Skywa-Primavesi in Vienna (1913–1915), which includes a large formal garden (as does the Palais Stoclet). Otto Primavesi took over Waerndorfer’s role as commercial director of the Wiener Werkstätte in 1915, and he and Robert became its principal underwriters after Waerndorfer’s financial collapse.

The idealistic but impractical Waerndorfer came from another rich Jewish family, whose profitable cotton mills allowed him to realize his aesthetic dreams. Yet this true believer’s unstinting support of the Wiener Werkstätte soon had disastrous economic consequences. As Witt-Dörring writes, “Waerndorfer’s absolute faith in Hoffmann’s genius oscillated between the extremes of ‘Can I afford it?’ and ‘I owe it to the world to afford it,’” but the latter attitude invariably won out. This Maecenas’s willful lack of caution eventually impoverished him; he immigrated to the US, became an artist, and during the Great Depression took up farming in a Philadelphia suburb, where he died a month before the outbreak of World War II.

Appropriately for a New York audience, the Neue Galerie exhibition includes a separate gallery on Joseph Urban, the Vienna-born architect who immigrated to the US in 1911 and was instrumental in bringing the Wiener Werkstätte’s concepts to the attention of an unprecedentedly large public. Although Urban designed one of Manhattan’s early modernist gems—the crisp gray-brick and strip-windowed New School for Social Research of 1929–1931, as fresh looking now as the day it was completed—his lucrative and highly publicized career as a stage decorator for the interwar years’ quintessential Broadway extravaganza, the Ziegfeld Follies, has overshadowed his other achievements.

Much less remembered today is Urban’s design work for Cosmopolitan Productions, the movie studio bankrolled by the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, in large part to advance the career of his mistress, Marion Davies, an erstwhile Ziegfeld girl. As art director on more than thirty Cosmopolitan films and with Hearst’s lush budgets at his disposal, Urban created settings that were either directly based on Wiener Werkstätte interiors or incorporated actual pieces made by the consortium.

He was particularly fond of the assertive designs of Peche, which veritably popped off the screen, including his boldly patterned white-turquoise-and-black Daphnis wallpaper, used by Urban for E. Mason Hopper’s The Great White Way (1924). And in E.H. Griffith’s Unseeing Eyes (1923)—for which, as Janis Staggs writes in her superb catalog essay, “perhaps Urban overcompensated for the dreadful picture by creating one of the most luxurious interiors he ever designed”—a cameo appearance is made by Peche’s silver-gilt and coral jewel box of 1920. Fifteen inches high and topped by a sprightly three-dimensional doe munching on grapes overhead, this bizarre but endearing caprice is on loan from the Metropolitan Museum, which has always been much more open-minded about collecting such oddities than the comparatively puritanical Museum of Modern Art.

Urban’s commitment to the cause went even further when he decided to establish a New York showroom for the Wiener Werkstätte in order to help its artists survive during a decade when America was prospering but Austria, like its World War I ally Germany, was mired in the economic depression that followed its defeat. In 1922 he opened a shop at 581 Fifth Avenue. America had never seen anything like it, starting with the octagonal, silk-paneled reception room dominated by Gustav Klimt’s nearly six-foot-tall canvas The Dancer, with a Klimt landscape and an Egon Schiele Madonna hung elsewhere on the premises.

But the same impracticalities that had dogged the Wiener Werkstätte for the two preceding decades persisted in Manhattan, where Urban perversely made it as difficult as possible for anyone to actually buy anything. Even well-disposed visitors wondered whether they were in a private home or a museum rather than a store. As Urban’s daughter Gretl reminisced years later, “It was funny to see father upset when one of his favorite pieces was being looked at by a potential purchaser.” No wonder the store lasted less than two years. Most of the pieces offered at a landmark show held in 1966 at New York’s Galerie St. Etienne—the first exhibition of Wiener Werkstätte designs in the United States since the Fifth Avenue outpost closed more than four decades earlier—came from the Urban family’s considerable stock of unsold merchandise.

3.

Interest in the nearly forgotten Wiener Werkstätte grew during the 1960s as part of a widespread Art Nouveau revival. But whereas the more psychedelic aspects of Art Nouveau that so captivated the Sixties counterculture were soon deemed passé, the work of the fin-de-siècle Viennese avant-garde became even more highly prized during the 1980s with the rise of Postmodernism. The proponents of that neotraditional style were eager for a return to pattern and ornament, which had been anathema during the half-century ascendance of the International Style, and they felt a strong kinship with the Wiener Werkstätte’s suave melding of Classical and early modernist elements.

Among the younger American architects most beguiled by Hoffmann and his coterie were Richard Meier (who during the 1970s began to collect turn-of-the-century Austrian design objects) and Charles Gwathmey. Both of them created china and metalwork, much of it based on the Wiener Werkstätte’s familiar quadratic motifs, for the Swid Powell company, which during the 1980s catered to the new vogue for objects designed by celebrated architects. But the Postmodernist most taken with Hoffmann was Michael Graves, who eagerly turned out furniture, products, and interior designs for numerous clients and modeled his practice after that of the multitalented Viennese master in an attempt to broaden the writ of the architect.

Being able to control all aspects of a large commission had immense appeal for those who, after the interchangeable-parts ethos of postwar modernism, wanted to achieve a cohesive look that would express a more grounded sense of place and be distinctively different from prevalent taste. Graves envisioned a return to the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) as sought by many artists around the turn of twentieth century, including Frank Lloyd Wright, the greatest American exponent of that concept, whose unified approach to all details of a scheme perpetually resonates with the public. But Graves soon faced the same dilemma that thwarted his many predecessors in the design reform movements: luxury objects, no matter how high the retail markup, are unlikely ever to be as profitable as plentiful machine-made goods.

Graves ultimately concentrated on moderately priced consumer items (for Alessi, Target, and other household product companies), while his architecture came to resemble super-sized kitchen gadgets. He got rich on royalties from his bird-topped Alessi teakettle (1.5 million units sold), but grew increasingly embittered as he dropped off the radar of the architectural press. Though he blamed his shift of critical fortune on a prejudice against those who don’t focus primarily on buildings, many thought the fault lay in the quality of his work rather than the genres he pursued.

Another distant echo of the Wiener Werkstätte now spikes the skyline of midtown Manhattan. The real estate mogul Harry Macklowe, developer of Rafael Viñoly’s 432 Park Avenue condominium tower of 2011–2015, revealed that while the building was under construction, a white-painted gridded-metal wastepaper basket created by Hoffmann in 1905 served as an “important touchstone” for the design. As Macklowe explained:

If you look at it very carefully you see a rhythm, you see a pattern, you see what we call push-pull between negative and positive. So that was very inspirational to Rafael Viñoly and I.

In fact, the extremely attenuated proportions of 432 Park—the world’s highest residential structure—make it more closely resemble Hoffmann’s white-painted metal vases, tall but narrow, which employ the same Gitterwerk (latticework) technique. (This design and its numerous variants became one of the Wiener Werkstätte’s most notable commercial successes.) But because a $225 reproduction of Hoffmann’s trashcan is on sale in the Neue Galerie’s gift shop, few commentators could resist citing it as a source for the $1.3 billion skyscraper. All the same, the transmogrification of an object devised for one purpose but grossly altered both in scale (whether bigger or smaller) and function meets the textbook definition of kitsch, even if its aesthetic is minimalist rather than naturalistic.*

Further evidence of the Wiener Werkstätte’s obsessive perfectionism but hopeless business model can be found in another Gitterwerk piece now on display at the Neue Galerie. At first glance, Moser’s silver breadbasket of 1904 would seem to be identical to Hoffmann’s better-known essays in pierced metalwork. Yet instead of hewing to either a flat or an evenly rounded surface like most of Hoffmann’s gridded metal objects, the approximately oval bread basket—ten-and-a-half inches long by two-and-a-half inches high—swells outward in five symmetrical pairs of curving segments, like the ground plan of a Bavarian Rococo pilgrimage chapel, and is a reminder of the playful eighteenth-century influences that lay beneath so much of the Wiener Werkstätte’s output, even early on.

However, when you look more closely at Moser’s apparently identical perforations you begin to realize that although every square seems to be equal, each turns out to be very slightly calibrated to compensate for the billowing curvature. This sleight of hand conveys an impression of uniformity that would not exist without exacting and costly attention to detail. Moser’s almost imperceptible and uneconomical deception—like so much else in the Neue Galerie’s dazzling treasure chest—helps explain why the grand illusion of the Wiener Werkstätte continues to enchant us a century after its frenetic heyday.

This Issue

January 18, 2018

Damage Bigly

Divine Lust

This Land Is Our Land

-

*

See my “New York: Conspicuous Construction,” The New York Review, April 2, 2015. ↩