The Los Angeles artist Laura Owens brings a light touch and a tough mind to a new kind of synthetic painting. Her exuberant, bracing midcareer survey at the Whitney beams a positive, can-do energy. As a stylist and culture critic, Owens is neither a stone-cold killer nor a gleeful nihilist, traits embraced by some of her peers. She’s an art lover, an enthusiast who approaches the problem of what to paint, and how to paint it, with an open, pragmatic mind. Her style can appear to be all over the place, but we always recognize the work as hers. Her principal theme may be her own aesthetic malleability.

Owens bends the conceits of art theory so that her own personality can flourish. She is not afraid of wit. Enchantment has its place too. Walking through her show, I was reminded of something Fairfield Porter once wrote about Pierre Bonnard: “He was an individualist without revolt, and his form…comes from his tenderness.”

For decades, and especially in the mid-twentieth century, a persuasive reading of modern painting revolved around the idea of the gestalt—the way every element in a painting coalesced into one totality, one essence that blotted out ambiguity. A painting isn’t a thing about another thing—it just is. This gestalt theory of painting was especially alluring during abstraction’s dominance; it put a brake on the drive for narrative, and helped to establish painting’s autonomy from literalist interpretations.

But a funny thing happened to the gestalt: life intruded. What if the whole is not more than the sum of its various parts, but more like a shopping list? What if all the various elements used to make a painting are just left out on the floor like pieces from a puzzle that no one bothered to finish? In a recent New Yorker profile, Owens thoughtfully implies that the time for gestalts is over, that collage—i.e., something made out of parts or layers—is simply a feature of the life we all lead. Indeed, a big part of our culture is involved with putting things together, with little distinction made between the invented and the found, and even less between the past and the present. The fragmentary, the deconstructed, even the deliberately mismatched—that is our reality. We are all collage artists now.

As someone who holds more or less the same view I can hardly fault Owens for believing this, but it seems to me that her paintings are very much gestalts anyway, though perhaps of a new kind, something closer in their effect to imagist poetry, and it’s their sometimes surprising gestaltness that holds our attention. Owens has interesting ideas, but it is her ability to give them form, often in unexpected ways sourced from unlikely corners of the visual world, that makes her art exciting.

Owens’s paintings are squarely in the middle of a postmodern aesthetic that’s been gaining momentum for the last ten or fifteen years. It is not the world of Luc Tuymans via Gerhard Richter, in which the painting’s photographic source is like a radioactive isotope that you could never touch but that, in its absence, is what really matters. The new attitude is not much interested in photography at all. It wants to rough an image up, put it through a digital sieve, and decorate the hell out of it.

A tree imported from Japanese painting anchors a wispy, airy composition. The tree shelters a monkey, or an owl, or a cheetah, perhaps borrowed from Persian miniatures—brown and khaki on a cream-colored ground, accentuated here and there by swatches of painted grids and colored dots, or beads or bits of yarn, or shapes cut from colored felt. An Owens monkey in a tree (or a Peter Doig canoe) is imagery augmented, repurposed. This is composite painting. It coheres, but maybe not in the way we’re used to.

Owens has a big formal range at her disposal—her quiver is full. Odd color harmonies: teal, hot pink, raw sienna, fuschia, manganese blue, cream. The colors of the decorator shop. Art taste that’s been knocked down a notch or two. The paint is applied with a pleasing paint-by-numbers quality. You can feel the hobby store just around the corner.

Paintings like illustrations in a children’s book. They feel liberated, unafraid to be garish. Saturated color and loose, agitated brushwork. Images that kids find appealing: animals in the forest, princesses, wild-haired children—fairy-tale stuff. The spirit of Magritte hovers over these paintings—his vache paintings from the late 1940s, the ones that nobody wanted.

A chunky white horse with a fanciful tail like a philodendron frolics against a loosely painted blue background (see illustration above). The horse is happy, energized; it lifts its head and kicks up a front hoof, straining at the confines of the rectangle. Everything about this painting from 2004 is right: the brushwork like china painting, the scale, color, and image all aligned. This quality feels instinctual—not something Owens was ever taught.

Advertisement

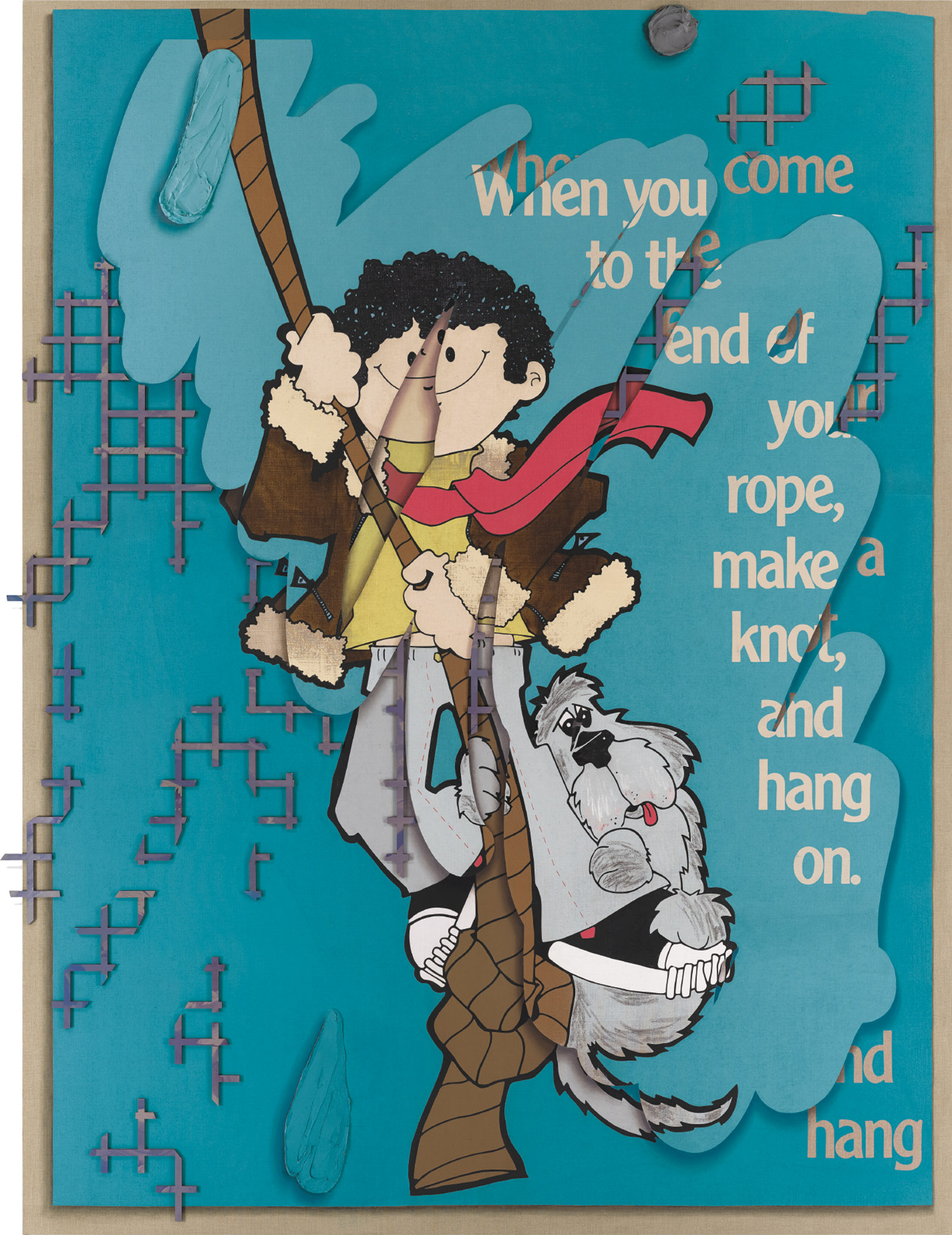

The paintings after 2005—a collage of grids in different scales colliding at different angles; a counterpoint of impasto freestyle painting, or silk-screened commercial imagery, or an expanse of text with the deadpan look of an old phone book. The compositions are retinal, assertive, like novel forms of candy seen in a glass jar. Their look is closer to greeting cards than to Franz Kline. This is strangely reassuring; they carry you along without protest, arbitrary, clownish, and weird.

The reciprocity of silk-screen and digital printing, the computer’s replica of the hand-made, are products of the coding mind of twenty-first-century painting. For artists of Owens’s generation (she’s forty-seven), the easy back and forth between found and made forms, and between painting and printing, is a given.

Sometimes the paintings are so casual-looking they can trip you up. In 2013, Owens showed twelve large (roughly twelve-by-ten-foot) paintings of this new postmodern composite type in the gallery space that occupies the ground floor of her Los Angeles studio, and people have been talking about them ever since. Paintings that leave the impression they could be, or do, just about anything. Perhaps their most salient quality is confidence. The digital enhancement of a sketch or doodle enlarged to twelve feet gives a vertiginous, Alice-in-Wonderland feeling to some of the paintings. Small grids on top of larger ones, hard-edged curlicues, computer-assisted drawings of cartoony Spanish galleons, red hearts and splashy arabesques, Photoshop lozenges and fat zucchinis of impasto thick as cake frosting, throbbing pinks and hot greens—all of it and much more is easily dispersed around the canvases, which were hung just inches apart, lest anything get too contemplative. The paintings don’t so much violate notions of good taste as ignore them.

Owens’s paintings sometimes seem to have been made by another kind of intelligence altogether, one tuned to a frequency similar to our own, yet different, as if a space alien, stranded here on a mission from a distant galaxy, had been receiving weak radio signals from Planet X. You can just about pick out the command from the static: unintelligible…static…static… Put raspberry-colored grid on aqua-colored rectangle. Add cartoon figures. Add black squiggles. Put drop shadows here and there. Don’t worry about placement—just put somewhere. Sign on back with made-up generic name. Try to pass as earthling until we can send rescue ship.

The critic most relevant to Owens’s work might be an Englishman who’s been dead for nearly forty years and never wrote about contemporary art. In his Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), William Empson concerned himself with the ways in which poetical language—motifs, figures of speech, even individual words—can mean more than one thing at a time. He wanted to know how a poet or dramatist uses linguistic constructions to convey both the complexities of character and a setting for interpreting their actions. A figure of speech inserted into the right narrative structure can evoke the unstable experience of a protagonist who chooses a course of action, but who retains an awareness of the things not chosen. In literature, certain words, certain figures allow the reader to feel that psychic rub: this and not that—but with a bit of that still present; the memory of what was not chosen hangs over the action. Empson also made an important observation about an author’s intention. He believed that an author could say something in the work that could probably not be said apart from it. This type of ambiguity in particular resonates with visual art.

When people talk about irony in painting, which they do quite a lot, what they usually mean is ambiguity. Irony is saying one thing and meaning its opposite, while ambiguity is the ability for a form to hold two or more meanings at the same time. Painting that trades only on irony can have a short shelf life. Ambiguity keeps on giving; it rewards prolonged looking. In painting, ambiguity is most often present in the imagery, in its references and connotations, as well as how that imagery is handled. The style, of course, inflects the feeling. This is true for Owens as well. What feels invigorating about her work is that the painting’s structure itself is also a marker of ambiguity. But even such painterly sophistication is not so rare; what really sets Owens apart is her dexterity at both kinds of ambiguity.

Advertisement

Take, for example, one of her works from 2013 (not pictured): a dense field of hot pink slashes on a pale lavender ground, overprinted with fragments of differently scaled grids in cadmium green, turquoise, or black—and that’s just the background. This eye-dazzler is covered with lots of wheels (eighteen!) of different sizes. Rubber tires on metal hubs or spokes—the kind of wheels found on tricycles, wagons, grocery carts, some brightly colored, Day-Glo even—are mounted on the canvas, parallel to its surface with just enough clearance to freely turn. Wheels punctuate the composition in a jaunty, syncopated rhythm—a chariot race without the chariots, a riot of implied motion on top of an already pushy abstract painting, not going anywhere, in perpetuity. Hilarious, breathtaking, circus glamour. The ghosts of Jean Tinguely and Charles Demuth, the Dada mind of Francis Picabia.

Then there are, across a narrow corridor from each other, a pair of pale robin’s-egg blue paintings of medium size, both covered with clusters of what look like hand-drawn, variously sized, random numbers, which, on a closer look, are made with thin, raised ribbons of black acrylic paint. The numbers on one painting exactly match those on the other in size and position, but reversed, as if one painting is looking at itself in a mirror. A hand-drawn mirror image of a random jumble of numbers. The conceit is witty and cartoony-weird. I have no idea what it means. It’s engaging and fun to look at. But the color! Other artists might have an idea for mirror writing in painting, but I doubt they would have expressed it with the shade of blue found in a tea shop or a girl’s bedroom. The surprising color choice gives the paintings an identity separate from whatever idea generated them.

One of Owens’s many strengths is her use of scale—the big painting and the internal relationship of shapes to the whole. She’s at ease with the large New York School canvas. Even though a lot has happened since, and no matter how anachronistic it may seem, our yardstick for serious painting is still shadowed by the achievements of the New York School. One of the hallmarks of that type of abstract painting is the “all-over” composition, in which the paint reaches all four edges of the canvas equally, and the eye roams through the picture in a nonhierarchical way. Owens extends and reinvigorates that tradition when she brings her affinity for textiles to the all-over, large-scale work.

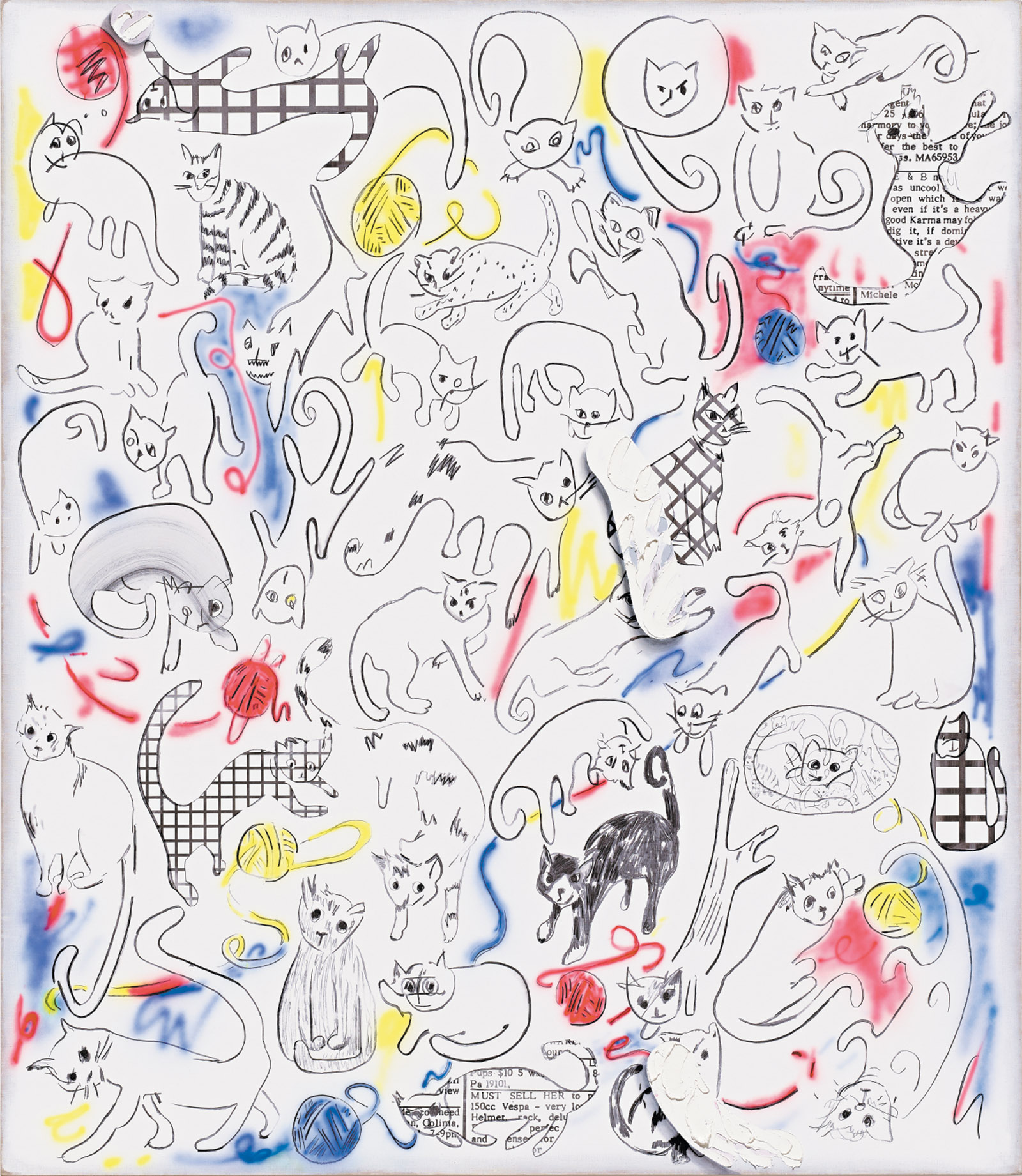

Textiles, weaving, 2-D design—all are full-fledged high art now, and Owens has no problem letting herself be influenced by them. Another of her works from 2013 is an almost twelve-foot-tall painting with line drawings of cats playing with balls of yarn dispersed over its white ground (see illustration above). Some drawings are carefully executed and others more slapdash; some are in plaid, others in the grid patterns that Owens is so fond of. Here and there are touches of spray paint in raspberry, yellow, and blue. It’s like a motif that one might find on a young girl’s flannel pajamas, something a sophisticated seven-year-old would find amusing and a bit arch. This is a painting that says: You want all-over? OK, how about this? This is the way to be ambitious now. You don’t always have to throw your Sunday punch.

The installation at the Whitney, overseen by Owens and Scott Rothkopf, the museum’s chief curator and deputy director for programs, restages exhibitions from Owens’s principal galleries in Los Angeles, New York, London, and Cologne. Walls were built, hanging plans copied—and the result resembles a Laura Owens theme park instead of a traditional retrospective that aims to situate works in relation to one another as well as to deliver the greatest hits. The reason is that much of Owens’s thinking about her work, its generating impulse, is tied up with the notion of site specificity. There is a continuous run of invention and forward-thinking bravado; painting ideas ricochet around the rooms. You can either run alongside and try to hop on, or just get out of the way.

I especially admire the way that Owens integrates her various sources and influences into her own pictorial vocabulary. The ability to be influenced in a productive way, which includes making one’s influences legible to the audience, might be essential to success in today’s art world—so much so that art schools should have a class in how to identify and use the myriad external points of reference from the visual world with which we make up our hybrid, signified selves.

Let’s recognize too the generative power of folk art and all of its derivations, including gift shop, decorator store, calendar, and greeting-card art, as well as technical drafting, computer graphics, and the look of giveaway supermarket magazines. Owens can mash or stack up all of the referents, compass points, familial overlaps, and personal curiosities into one tightly compressed, orderly bundle. Hers is the painting equivalent of the machine that turns cars into a solid, dense cube of crushed metal. Owens’s work doesn’t look squashed—quite the opposite: its surface is open and inviting, but the structural components appear indivisible.

As an image gatherer, Owens is peripatetic and astute. An estate sale yielded the source for an especially winning group of paintings from 1998: a crewel-work pillow enlivened with a swarm of honeybees arrayed around an orange-hued, dome-shaped hive (see illustration below). As much as anything else in the show, the sure touch involved in successfully translating that image of wishful good vibes to a painting convinced me of Owens’s superior pictorial instincts. Her bees are made with thick blobs of black and yellow acrylic paint, their wings rendered as delicate black lines with veins of iridescent white, and the dozen or so insects hover and float on an expanse of unpainted cotton canvas. The four tones—coral orange, cadmium yellow, deep burnt sienna, and umber, which together create an illusion of volume—form a perfect chord of color harmonies. The beehive paintings are secure in their directness and shorthand styling. They have what in the theater is called good stage manners: every decision is bold, clear, and appropriate.

Owens’s work is part of the American pragmatic tradition. The intellectuality in her work feels new to me. As a thinker, Owens is self-reflexive, curious, and matter-of-fact. As a stylist she’s resourceful and fearless. She’s braided into the same rope with a few older painters, such as Albert Oehlen or Charline von Heyl, or, closer to her own age, Wade Guyton or Seth Price, but she doesn’t share their angst or spiky black humor. In fact, Owens doesn’t seem to have a nihilistic bone in her body. Her work incorporates ambiguity as part of its structure, but the paintings are not difficult or withholding. Like a character in a screwball comedy, they wear an expression that says, I don’t know what happened, Officer; one minute I was just standing here, and then…

The 663-page catalog that accompanies the exhibition is generous and full of anecdotes. Many voices are heard: the artist’s mother, her fellow artists, dealers, novelists, curators, and critics all contribute their shadings to Owens’s rise. The book is a hybrid literary form, a bildungsroman with pictures: the story of an earnest young woman from the provinces with an appealing, straightforward manner who, through luck and pluck and the benevolent intervention of some well-placed patrons, grows up to see her dream of being an artist realized.

A blizzard of faxes, letters, clippings, photographs, and invoices to and from Owens and her dealers and peers shines a light on the world of professional art schools and the international network of galleries and alternative spaces that are the mechanisms of generational renewal. Owens approaches art-making with a democratic spirit, in the naturally collegial way that comes easily when you’re young. The catalog represents a welcome acknowledgment that any career of real substance is also a group project. That Owens so readily embraces that reality may be a gender thing; her male counterparts still cling for the most part to the “prickliest cactus in the desert” mode, tiresome though it has become.

It has been terribly important to Owens that her paintings call attention not only to the conditions of their own making, but also to the social nexus in which they participate. The work of art is one link in a chain that includes gallerists, curators and critics, her fellow artists, and of course the viewer. This focus on the social system of art is, in part, the legacy of conceptual art as it has been filtered through the language of painting. Owens makes being a good citizen into an aesthetic.

Probably many people can identify with the trajectory of Owens’s life. I know I can. Midwestern and middle-class, Owens as a teenager looked at paintings, noting which ones held her attention and why. She developed her skills at summer art camp, going off to college at RISD, and on to CalArts for grad school. This is how artists today are made: from avid teenaged drawer and painter to RISD adept who then finds herself questioned by the hard-liners for whom painting was a lost cause. It’s a great recipe when combined with talent and drive. By the time Owens got to grad school, she had sufficient self-confidence to survive the ritual hazing known as the group critique. Although Owens put in her time at CalArts, that hotbed of conceptualism with the arch-enforcer Michael Asher, it doesn’t seem to have done her any harm, possibly because she was so clear about her vocation from an early age.

What a relief to have a painter who didn’t get the stuffing knocked out of her at the Whitney Independent Study Program or its equivalent. A strong design sense, internalized early on and reinforced at critical junctures by encounters with Chinese painting, or Matisse, or Bauhaus textiles, can carry you through a whole career. You can add the conceptual icing, which is what the tuition buys at schools like CalArts, but you’d better bring your own cake.

Owens takes the world of design, especially children’s books and child-friendly graphics, and teases out the forms that can be recast as art. Put another way, she has an instinct for choosing the right thing and knowing what to do with it. Her work has no anxiety about being nerdy, or not much anxiety period. This is art that’s comfortable wearing fuzzy slippers.

Owens’s work is the apotheosis of painting in the digital age. The defining feature of digital art—of digital information generally—is its weightlessness. Images, colors, marks, text, are essentially decals in a nondimensional electronic space. They exist, but only up to a point. They can excite the mind, but you can’t touch them. An air of weightlessness remains even when they are transferred to the physical surface of a painting. If these images were to fall, nothing would catch them. They’re like Wile E. Coyote running off a cliff, just before he realizes he’s churning air.

Owens is part of the ongoing process of loosening the rules governing how a painting acquires meaning that began with the young painters of the late 1970s and early 1980s (of which I was one). The general idea was to dissolve the gravitational force field that held the disparate elements of a painting together, like atoms bundled into a molecule. This “glue” was, and is, invisible to most viewers, just as it is in life generally. These artists wanted to make it visible, as though shining a black light on a painting to reveal the cracks in its surface. And they wanted to move painting out from under the infuriating drone of high-culture pieties, which had lost much of their credibility. There was a low-grade, cheerful nihilism in much of that work, but it didn’t go very far on the rebuilding side.

The whole project eventually got absorbed into criticism as the original artists moved on to other things. The field lay fallow for some years. Eventually, it fell to artists of Owens’s generation to replant. Owens, whether using embroidery, the computer, painted forms, or screen printing, stumbled on a hidden truth that has been more or less obscured since the late 1980s: the relationship between form, visual logic, and emotional catharsis is itself ambiguous.

A strange thing happens after you spend some time at the exhibition. Once you become acclimated to the endless malleability of the prosaic that is at the heart of Owens’s visual syntax—Oh, this is actually not something found at the mall—what follows is like a tiny paint bomb that detonates in the mind’s eye, which leads in turn to a strange and unexpected hollow sensation. It’s the tart pinch of a correction you feel after the cheering stops. The effect of Owens’s work, with its ebullient leap-frogging into worry-free zones of pictorial busyness, can sometimes feel, to paraphrase John Haskell, like waiting for the happiness to arrive.

I can’t fully explain why, but walking through the show I had the feeling, as I rounded a corner, of a dream of falling, one that was deprived of its conclusive ending when you hit the floor and wake. Pictorial free-fall—it’s thrilling, and quite unnerving. But no matter, just let it go. I was reminded of what the iconoclastic film critic and painter Manny Farber wrote in 1968 at the end of his review of Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise: “No other filmmaker has so consistently made me feel like a stupid ass.”

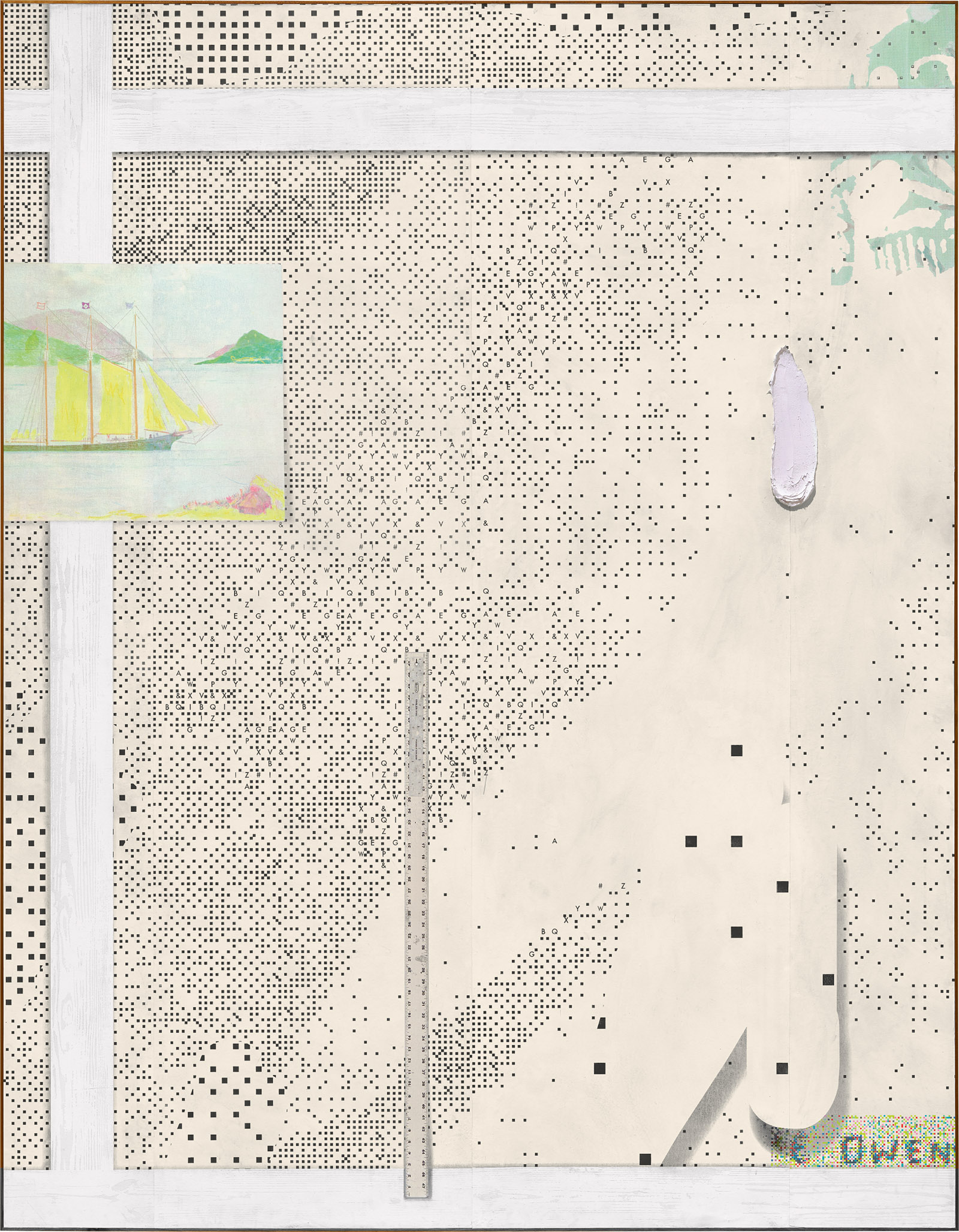

The last room at the Whitney contains three large paintings that were part of a complex installation made for the CCA Wattis Institute in San Francisco in 2016. Though clearly related to other paintings in the show, they have a different gravitas. Their terse, shimmering surfaces are made from black-and-white fields of digital static. Amorphous sprays of x’s and o’s and other pixilated data are the result of various objects put through a scanner, digitally manipulated, enlarged or reduced, allowed to play out in large swaths, and sometimes corralled into shapes with drop-shadow edges. These compositions are then printed on paper and glued to aluminum panels. The silvery-gray tones and irregular patterns recall barren terrain seen from the air. The paintings are bisected near their edges by vertical and horizontal bands of white, and here and there with bits of color (see illustration above). They suffer in reproduction—there is a sound component to them as well—but their austerity, resourcefulness, and sense of resolve are impressive. I found them, and much else in the show, beautiful, dramatic, and moving, and a strong case for painting’s digitally assisted future.

This Issue

February 8, 2018

To Be, or Not to Be

Female Trouble

The Emperor Robeson