Some artists start out with a bang, others with barely a whisper. The trumpeter and composer Wadada Leo Smith, one of the most influential figures of the postwar black musical avant-garde, could not have begun his career more quietly. In 1972, Smith, then a thirty-one-year-old musician living in New Haven, released a solo album called Creative Music—I, on which, besides trumpet, he played flugelhorn, wooden flute, harmonica, hand zithers, and an assortment of percussion instruments set up on steel poles: bells, gongs, xylophones, cymbals, whistles, aluminum pot drums, metal plates. And for long periods of time, Smith did not play at all. Instead, he allowed silence to fill the space of his music.

Not many people heard Creative Music—I when it first appeared, but its contemplative radicalism was not lost on those who did. Smith was returning to the foundations of music: sound and silence, articulation and breath. While he drew inspiration from the free jazz revolution that had begun more than a decade earlier, his own sensibility could not have been further from the style of free jazz known as “energy” or “fire” music. Loud, intense, often frenetic, fire music suggested a primal scream repressed for too long. The meanings of the scream were spelled out by the album titles of the period: political (Jackie McLean’s Let Freedom Ring), erotic (Alan Shorter’s Orgasm), sacred (Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity), cosmic (John Coltrane’s Interstellar Space). For much of the 1960s, it was contagious. Even Miles Davis, the great poet of space and stillness, who claimed to disdain the cacophony of free jazz, ended up embracing the noise, playing fierce, jabbing notes against roiling backdrops of electric guitars on albums like Bitches Brew and Jack Johnson.

A quiet fire burned in Smith’s music, but more often it suggested water and wind. Some of his titles resembled haikus: the first track on Creative Music—I was titled “Nine (9) Stones on a Mountain.” While most free jazz channeled the coiled energies of the great northern cities, Smith evoked the vast rural landscapes of the Mississippi Delta where he had grown up. Formally, his music was more radical than fire music, less encumbered by traditional song forms. But his was a pastoral modernism: spacious, serene, and in no hurry to reach its destination. Smith was not the only pastoral modernist to emerge from the ranks of the free jazz movement. His friend Marion Brown, an alto saxophonist who evoked memories of his rural Georgia childhood, and Don Cherry, a fellow trumpeter who created an imaginary folk music while wandering through North Africa and Turkey, also worked in this vein. But Smith would become its most committed exponent, and the most systematic: an “organic intellectual,” in the words of George Lewis, a trombonist and composer who has known him since the early 1970s.

Smith’s unusual feeling for time was also distinctly southern, nourished by his childhood memories of rural Mississippi and governed by a nonmetrical approach that he called “rhythm units,” in which a long sound was followed by a long silence, a short sound by a short silence. The place of silence in his music reminded some early listeners of John Cage, a composer he admired, but Smith attributed it to jazz musicians who had “a style of phrasing that included silence within the context of a phrase,” among them Lester Young, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, and, not least, Thelonious Monk, who spent his first five years in North Carolina before moving to New York City in the Great Migration.

Silence also served a different purpose in Smith’s music than it does in Cage’s. Smith did not want to surrender control or subjectivity to chance, but to assert them: his music was willful rather than a renunciation of will. And the effect of his silences was to draw attention to the beauty of his trumpet playing: stately and soaring, alternately buoyant and plangent, it is indebted to the modernism of Davis, Booker Little, and Don Cherry, yet equally reminiscent of the brassy, southern ebullience of Louis Armstrong. As the French writer and philosopher Maurice Blanchot wrote of Stéphane Mallarmé, Smith’s trumpet seemed to emerge miraculously out of “nothingness…whose secret vitality, force and mystery it carries out in meditation and in the accomplishment of its poetic task.”

Since the release of Creative Music—I nearly a half-century ago, Smith’s music has evolved in a number of directions, but he has continued to work with rhythm units, and to draw on the power of silence and negative space. On his extraordinary new album, Solo: Reflections and Meditations on Monk, he applies these principles to the pianist and composer, whose centenary was last year. The album includes four of Monk’s best-known ballads: “Ruby, My Dear,” “Reflections,” “Crepuscule with Nellie,” and—the album’s haunting finale—his most famous tune, “’Round Midnight.” The other four tracks are original compositions that Smith describes as “profiles” of Monk. (Two are, in fact, the same piece, an adagio performed with, and without, a mute.) Their titles offer visual descriptions of Monk—one imagines him at Shea Stadium with the pianist Bud Powell, another at the Five Spot Café, where Monk played extensively in the late 1950s, wearing a five-point ring—and the music is embedded with shadowy allusions to Monk’s work.

Advertisement

Solo: Reflections and Meditations on Monk emerged much as Creative Music—I did: not in the cutting contests of onstage combat, the traditional testing ground of jazz creativity, but at Smith’s home in New Haven. Twenty-five years ago, a pianist friend gave him a book of Monk piano transcriptions by Bill Dobbins, and he began practicing them in his spare time. He particularly liked the ballads (or as he calls them, adagios) because “they allow me to really express my tone.” He played them as if the bar line didn’t exist, organizing the music with rhythm units rather than chord progressions, so that the pieces would “flow like a wave, and…people can ride that wave with me.” He decided to record these pieces on solo trumpet because “the essence of Monk is, I believe, in his solo performances.” Smith thereby reveals their brilliant corners, the way they lend themselves to “expansions and further explorations,” while at the same time presenting himself as a student paying homage to a great teacher. All that one hears is the celestial sound of Smith’s trumpet and the silences around it. The music could not be sparer or richer.

“Most people would never realize that I am closer to Thelonious Monk than to any other artist,” Smith writes in his liner notes. He is not exaggerating. Smith has paid homage in his song titles to many jazz musicians, but never to Monk. Nor has he ever displayed the characteristics typically associated with Monk, such as angular melodic turns, eccentric phrasing, and impish humor. But as Smith goes on to observe, Monk, with his exceptional sensitivity to the spaces between notes, understood silence not as “a moment of absence,” but “as a vital field where musical ideas exist as a result of what was played before and after”—the same principle that underlies Smith’s rhythm units. On Solo: Reflections and Meditations on Monk, Smith elongates and intensifies Monk’s silences until they sound like his own. This transformation, far from betraying Monk, distills the lyricism, tenderness, and yearning at the heart of his melodic writing.

“I see Monk as a…mystical philosopher,” Smith, who is seventy-six, told me at National Sawdust, a theater in Brooklyn, where he performed in late October. “I once heard a writer ask Monk, ‘What’s the meaning of life?’ And Monk said the meaning of life is death. And I thought that was the most perfect answer, because every breath we take…is leading to that magnificent moment. It’s the other end of the journey, and it’s all connected to the first big bang, the first breath of life. And…death is not a concept only of leaving, but of change, or transformation.”

“The second reason” he was drawn to Monk, he went on, is that “he spent a lot of time in isolation, and I did the same thing. The reasons were essentially the same: no one would hire us.” Monk’s cabaret card, which was required to play at clubs in New York City until the early 1960s, was revoked on several occasions, on mostly spurious charges of narcotics possession. But as Smith notes, “He didn’t sit around thinking about that: he actually kept developing and developed so uniquely that that isolated moment was probably a gift from the Almighty, just as mine was. I didn’t sit around, I didn’t feel left out. I did my research…. I performed every week in my house, not for people—for me.” He would tape his performances and then examine the tapes for “flaws in musical direction, flaws in conceptual design,” as well as in “how well I received the inspiration that I was trying to transmit. And what I discovered…was something about sound and silence,…about nonmetrical movement, where you don’t have to be in beat or in time, but you connect with the universal time, which is more like a wave as opposed to a beat.”

Smith’s research has yielded what is now widely recognized as one of the most innovative bodies of work in American music since the 1960s. The last decade or so has been the most fertile period of his career. He leads an electric ensemble called Organic, and a more traditional jazz group called the Golden Quartet. He has written for string quartet, orchestra, and solo cello, as well as for gamelan and koto ensembles. His four-hour reflection on the civil rights era, Ten Freedom Summers, written for a quintet version of the Golden Quartet and a nine-piece chamber orchestra, was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in 2013. Smith’s ravishing “graphic” scores—small, delicate sketches that in their combination of abstract imagery and symbols recall Kandinsky and Klee—have been the subject of recent exhibitions at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the Renaissance Society in Chicago.

Advertisement

Just before we spoke at National Sawdust, Smith played a solo version of “Ruby, My Dear,” a song Monk wrote for his first love, at his sound check. He rendered its exquisite melody with little embellishment except for his signature silences, as though he were leaving a place for Monk’s ghost to enter the room. After a brief improvisation (or “creation,” as Smith prefers to say) and a reprise of the melody, he suddenly stopped. “I felt it was finished,” he told me. “People often play past their inspiration…. It’s OK not to play sometimes because your presence on stage, whether you’re playing or not, influences the music.” That afternoon, he was dressed in a kind of black smock, with the stack of dreadlocks he has worn since the early 1980s, when he converted to Rastafarianism and added Wadada to his given name, Leo Smith. (He later converted to Islam and made the Hajj to Mecca in 2002, adding yet another new name, Ishmael, before Wadada.) He rarely moved from a fixed position except to huddle, as if the force of his horn depended on sustained physical compression. Like his music, his onstage presence has a riveting stillness.

Leo Smith was born in 1941 in Leland, Mississippi, “a town so small you could walk from one end of it to the other in a minute.” He has not lived there since the early 1960s, but his drawl is still as thick as jam, and he often expresses nostalgia for his southern childhood. Although he grew up in town, where his mother worked as a cook, he spent his summers picking corn, cotton, and soybeans on his grandparents’ farm. (He still draws on agricultural metaphors to describe his work, likening the trumpet to a flower, the breath projected through it to a seed.)

Smith started out on mellophone and French horn, before switching to trumpet when he was twelve. (He had first “received” music in church, “like all dark people do.”) His first important musical influence was his stepfather, the electric blues guitarist Alex “Little Bill” Wallace. Elmore James, B.B. King, and Little Milton often stopped by the house to play on the weekends. Smith was “mesmerized” by the stories these bluesmen told in their songs, and impressed by how their lyrics combined profundity and brevity. Many of their songs were about women loved and lost, but he realized that women were really a “metaphor for transformation,” much like references to wine in the Sufi poetry he would later read. “The Blues was my first language and it never went away,” Smith says.

By the time he was thirteen, he was playing the blues at a local whites-only country club. He entered through the kitchen, where he was instructed to look neither left nor right, and, above all, never to make eye contact with guests. Looking at a white woman could get you killed.

At nineteen, Smith left Mississippi to join the army. But the Delta—its blues, its natural beauty, its slowness—left an indelible imprint on his musical imagination. “When you come up in Mississippi and you walk out in the morning before sunrise,…there’s nothing in front of you except a long open field. And you watch the sun come up out of the ground,…past your knees,…past your chest and past your head, at every one of those moments I’m amazed, because, look, I’m taller than the sun, and when the sun passed my head, I realize, I’m just a speck.” In this humbling “zone of transition,” with its natural cycles of presence and absence, he found “an organic link of sound and visual and silence.” He honed his technique by practicing outdoors: on the front porch, in the fields, even in the woods, where he noticed how the sound of his horn would slowly fade away as he reached the edge of the forest.

In 1967, after five years in the army, Smith settled in Chicago and joined the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a not-for-profit black musicians’ collective and conservatory founded two years earlier by the pianist Muhal Richard Abrams and three other musicians. Abrams, who died in late October at eighty-seven, envisioned the AACM as a laboratory for generating original forms and structures for avant-garde jazz, or what he called “creative music.” In the AACM, Smith found himself among such kindred spirits as Roscoe Mitchell and Anthony Braxton, saxophonists who shared his fascination with the properties of sound. Before long, he distinguished himself as an adventurous composer and improviser. Although his work was steeped in blues and jazz tradition, that knowledge revealed itself in extremely subtle ways, rather than in recognizable “licks” or riffs, much less grooves.

Puckish off-stage, Smith cut an earnest, ascetic profile in performance: unlike the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the AACM’s best-known group, he had no interest in the aesthetics of collage, ironic citation, or absurdist mischief. The Creative Construction Company, the band he formed with Braxton, the violinist Leroy Jenkins, and the drummer Steve McCall, was one of the most experimental ensembles of the AACM. It was also, by his own admission, one of the least loved. “We were like the outside guys,” Smith recalls in George Lewis’s history of the AACM, A Power Stronger Than Itself. “Notions of silence, rhythmic design, directed motion, those kinds of things were very different from the notion of playing the greatest solo or cutting everybody to pieces that you’re playing on the same stage with.”

During a year-long sojourn in Paris from 1969 to 1970, Smith managed to thoroughly confound French critics, who did not know what to make of a style that rejected all the clichés of the fire music that many of them considered an expression of black authenticity. “We would drop a silence bigger than a table. What do you do? Do you say, hey, gimme another drink, or what?” On his return to the United States, he moved to New Haven and went into near seclusion. He studied the scores of Charles Ives and Carl Ruggles; read Emerson, Thoreau, and Frederick Douglass; and took classes in ethnomusicology at Wesleyan, where he discovered the affinities between black American music and the improvisatory traditions of West Africa, Indonesia, and Japan. He visited New York occasionally to see friends, but left his horn at home, since he had no interest in session work, and felt in any case that New York was “almost lost as a place of creativity.”

Having exiled himself from the New York scene, Smith created his own, surrounding himself with like-minded young musicians: the alto saxophonist Marion Brown, the pianist Anthony Davis, the drummer Pheeroan akLaff, the bassist Wes Brown, and the vibraphonist Bobby Naughton. He established his own label, Kabell Records, and recorded a series of albums, starting with Creative Music—I. (These recordings were released in 2004 by John Zorn’s label, Tzadik, in an extraordinary box set, Kabell Years: 1971–1979.) He also self-published a series of theoretical writings, such as notes (8 pieces): source a new world music: creative music, a 1973 manifesto permeated by the revolutionary romanticism of the Black Arts Movement. In notes (8 pieces), Smith calls for a new set of aesthetic criteria proper to black improvised music and looks forward to the day when “the creative music of afro-america, india, bali and pan-islam…will eventually eliminate the political dominance of euro-america in this world.” In order to take part in this cultural and political struggle, musicians would have to declare independence from the music industry (“this factory of death”) and develop a “heightened awareness of improvisation as an art form.”

But perhaps the most revolutionary feature of notes (8 pieces) is the way it used the language of cultural nationalism to upend narrow cultural nationalist assumptions, particularly those having to do with black music’s relationship to percussion. Smith took particular exception to the “fallacy that if the drum is not present then it is not black music (creative music).” Louis Armstrong’s most famous recordings, after all, did not include drums, and yet “the spirit-essence of the drums is there.” This essence, from which black creative music derived its power and originality, was more fundamental, if less immediately audible, than its external trappings. He had discovered it by exploring rhythm units and the “space silence that is the absence of audible sound-rhythms,” and, as he wrote in a rapturous passage, it had opened his eyes to

the wonder and gorgeousness of nature—i’ve heard the sounds of the crickets, the birds, the whirling about and clinging of the wind, the floating waves and clashing of water against rocks, the love of thunder and beauty that prevails during and after the lightning—the toiling of souls throughout the world in suffering—the moments of realization, of oneness, of realness in all of these make and contribute to the wholeness of my music—the sound-rhythm beyond…expression that is clothed in the garment of improvisation…. it is what makes my life complete with all its suffering and all of its pleasures and all that makes life life.

“I was arguing with the planet,” but especially with musicians “born into the North,” Smith said when I was asked him what inspired him to write notes (8 pieces). “In the South you look for essence. You don’t look just for the table, you look for the essence of the table, [which is the] seed—it’s not a tree. It’s a seed that sprouted into this wood thing.” That search led him to invent not only the idea of rhythm units, but the visual language of “Ankhrasmation,” a system of vivid, multicolored drawings that he has often used to inspire musicians in improvised settings. (“Ankhrasmation” is a portmanteau of Ankh, the Egyptian symbol for life; ras, the Ethiopian word for leader; and ma, for mother.) With rhythm units and Ankhrasmation, Smith devised a system to structure his work and to teach other musicians to play it, but it was supple enough to allow for intuition and spontaneity. Explaining the impact of Ankhrasmation on the actual sound of Smith’s music is somewhat elusive; but then, as the pianist Craig Taborn, who has worked with Smith, told me, “so much of Wadada’s work resides in its mystery.”

For the first half of his career, Smith was known for a pensive, nearly ambient form of spiritual jazz. It shimmered with enigmatic, painterly timbres on works like Divine Love (1979), which featured an ensemble of Smith and two other trumpeters, a bass clarinetist, double bass, and vibraphone; and The Burning of Stones (1980), a piece for Smith’s muted trumpet and three harps that evoked Japanese court music. (Smith was formerly married to a Japanese poet, Harumi Makino, and has long been fascinated by Asian music.) But this ceremonial lyricism is only one aspect of Smith’s body of work, which has grown far less austere and far more accessible since his early investigations of rhythm units. He has explored reggae beats, recorded with the great Zimbabwean chimurenga singer Thomas Mapfumo, and, with his Golden Quartet, helped to extend the vocabularies of modal and electric jazz that Miles Davis pioneered in the 1960s and 1970s. Smith’s vernacular inspirations, particularly blues and funk, have become more pronounced, his playing hotter and more propulsive, as if he now felt liberated to draw upon all the influences he had succeeded in purging from his rigorous youthful modernism.

Smith has also tried to connect his music more directly to questions of spirituality, racial justice, and ecology, concerns often invoked in notes (8 pieces). In the somber, preacherly large-scale works that have consumed much of his energy over the last decade—The Great Lakes Suite, America’s National Parks, and Ten Freedom Summers, which he recently performed in Alabama—the United States appears as a land of epic promise, ravaged by internal demons. America in the civil rights era is the nominal theme of the monumental Ten Freedom Summers, but it looks back to the Dred Scott decision of 1857 and all the way forward to September 11, 2001, as if to suggest that the latter tragedy cannot be fully absorbed without a candid reckoning with what America has, and has not, been to its own people. A mournful blues performed by the Golden Quintet, “September 11, 2001: A Memorial,” is, in my view, the most haunting piece inspired by the event, a work that invites comparison with “Alabama,” Coltrane’s 1963 elegy for the four girls killed in the Birmingham church bombing.

For all the minimalism of his sound, Smith has turned out to be a maximalist in his ambitions, evolving into one of our most powerful storytellers, an heir to American chroniclers like Charles Ives and Ornette Coleman. Smith’s portrait of Thelonious Monk appears to unfold on a smaller canvas, harking back to the intimacy of his early solo work, but this impression is misleading. Performing Monk without accompaniment, after all, is a mountain that few musicians dare to climb, and Wadada Leo Smith has spent his life preparing for this moment. Through patience, humility, and, above all, silence, he has reached the top of that mountain, and rewarded us with the glorious culmination of a career devoted to the “divine love” of creative music.

This Issue

February 8, 2018

To Be, or Not to Be

Female Trouble

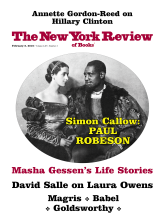

The Emperor Robeson