During the months of unrest that culminated in his ejection from the throne of Iran in January 1979, Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi oscillated between repression and leniency, rifle fire and mea culpas. Since coming to power on his departure, the clerical leaders of the Islamic Republic have concentrated on avoiding the Shah’s mistakes, elevating consistency and an unfaltering will into high principles of state.

The country’s current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, demonstrated these qualities in the summer of 2009, when he faced a vast outpouring of anger provoked by a fraudulently conducted presidential election. At a chilling Friday Prayers in Tehran on June 19, which I attended, Khamenei declared valid the reelection of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and warned millions of demonstrators to go home or expect “bloodshed and chaos.” Over the next couple of months, the minority of protesters who defied his warning were chased, beaten, and shot in the streets; torturers went to work on detainees in prisons; and state television broadcast the “confessions” of broken men in show trials. That autumn the universities expelled dissident students, and there was an exodus abroad of depressed young people. This huge, exuberant, but ultimately deferential agitation—regime change was not its purpose—was smashed with embarrassing ease.

The protests that erupted in Iran for a week or so at the end of December and the beginning of January attracted only a few tens of thousands, by contrast, but they were more widespread than those in 2009, affecting some eighty cities and towns across the country. They started in the northeastern city of Mashhad but spread as far as Izeh, in the far west, and Ghahderijan, in the central province of Isfahan. Rising living costs along with budget proposals to raise gasoline prices and cut monthly assistance to the middle classes were the spark, though the demonstrations soon took on a more radical flavor than the earlier protests, with calls of “Death to Khamenei!” and attacks on banks, shops, cars, paramilitary installations, and a mosque.

The state’s response was uneven. In Tehran the authorities managed to quell the protests by flooding sensitive areas (such as the neighborhood around Tehran University) with armed men; they were less prepared in the smaller towns, where around twenty-five people—including at least one member of the security forces—were killed. Several thousand people were arrested, two of whom later died in detention in suspicious circumstances.

I was in Tehran, staying with my Iranian parents-in-law, and it was immediately apparent that while many Iranians shared the rage of the mostly young, male protesters—against the state’s hypocrisy and intrusions, the siphoning off of wealth, the stifling of personal freedoms—they didn’t seriously contemplate joining them. In 2009 every member of my circle of friends in Iran was demonstrating for the limited goal of reversing a sham election. This time none took part. Many disapproved of the vandalism and destruction. There were also widespread suspicions that the protests had been manipulated, whether by agents provocateurs working for malevolent state institutions or by outside powers.

But the main reason the protests did not become a mass movement was a fear of the consequences on the part of those Iranians who, for all their frustrations, have families and livelihoods and assets to lose. The issue wasn’t electoral fraud or the perennial struggle between reformists and hard-liners, but something entirely different—the fate of the Islamic Republic. The protesters’ goal, ill-defined though it was, was not to reform the regime but to hurt it—mortally, if possible. At present most Iranians are still some way from sharing that objective.

During the protests President Donald Trump tweeted about his “respect for the people of Iran as they try to take back their corrupt government,” and also pledged “great support from the United States at the appropriate time.” But for many Iranians there may never be an “appropriate time” for revolution or regime change, with their prospects of slaughter, mass looting, and outside intervention, and beyond that the awful possibility that the most stable country in the Middle East might become another Syria.

Where do things stand in Iran now, with the nuclear deal threatened by an erratic US president, with the country engaged in a struggle for regional dominance with Saudi Arabia, and with at least 850,000 Iranians entering a labor market every year that has room for only 650,000 of them? This question would be easier to answer if Iran were as static as it is often depicted in the foreign media. But it is already in the throes of several revolutions.

Sexual liberalization, consumerism, and social media are rocking a society that has recently become overwhelmingly urban, and will become more so as the countryside continues to turn into desert. (Droughts have emptied villages across the Persian plateau, and 90 percent of Lake Urmia, once the sixth-largest saline lake in the world, has evaporated.) Over the past decade or so the Persian language has been infused with English phrases and concepts from the Internet, while American and Japanese technology (there are some 30 million smartphones in Iran), Turkish soap operas, and Chinese-manufactured goods slowly destroy the blend of homespun creativity, Shia observance, and close-quarter living that one might call traditional Iranian culture.

Advertisement

This, broadly, was the culture from which the Islamic Republic arose, undergirded by a fawning reverence for old age and male authority in the home, the workplace, and the top of the state. But these patriarchies have also been weakened by changing social mores and a generation of university-educated women. Back in 2009 a crowd shouting “Death to Khamenei!” was a terrifying novelty. This New Year’s it became a commonplace. Another principle under threat is the wearing of the hijab, which is gradually becoming optional in the more adventurous areas of north Tehran, while booze is in such hot demand that bootleggers don’t even bother to provide “scotch” whisky that tastes or looks like the real thing.

I watched two films in Tehran cinemas whose jokes about sex and pill-popping would not have passed the censors five years ago. Both films highlighted the destructive power of social media and, in the case of Side-Mirror (about a joyriding couple who damage a Maserati side-mirror that is worth more than their combined worldly possessions), economic envy. Who nowadays remembers those government officials who shortly after the revolution drew no salary and lived with their parents, or the peasant women who walked miles during the conflict between Iran and Iraq in the 1980s to donate an egg or a bag of melon seeds to the war effort? In the words of one European executive who recently moved to Iran with his family, and whose social life consists of visiting one opulent penthouse after another, “Having lived in Tehran and Moscow, I’d say the wealth here is more conspicuous.”

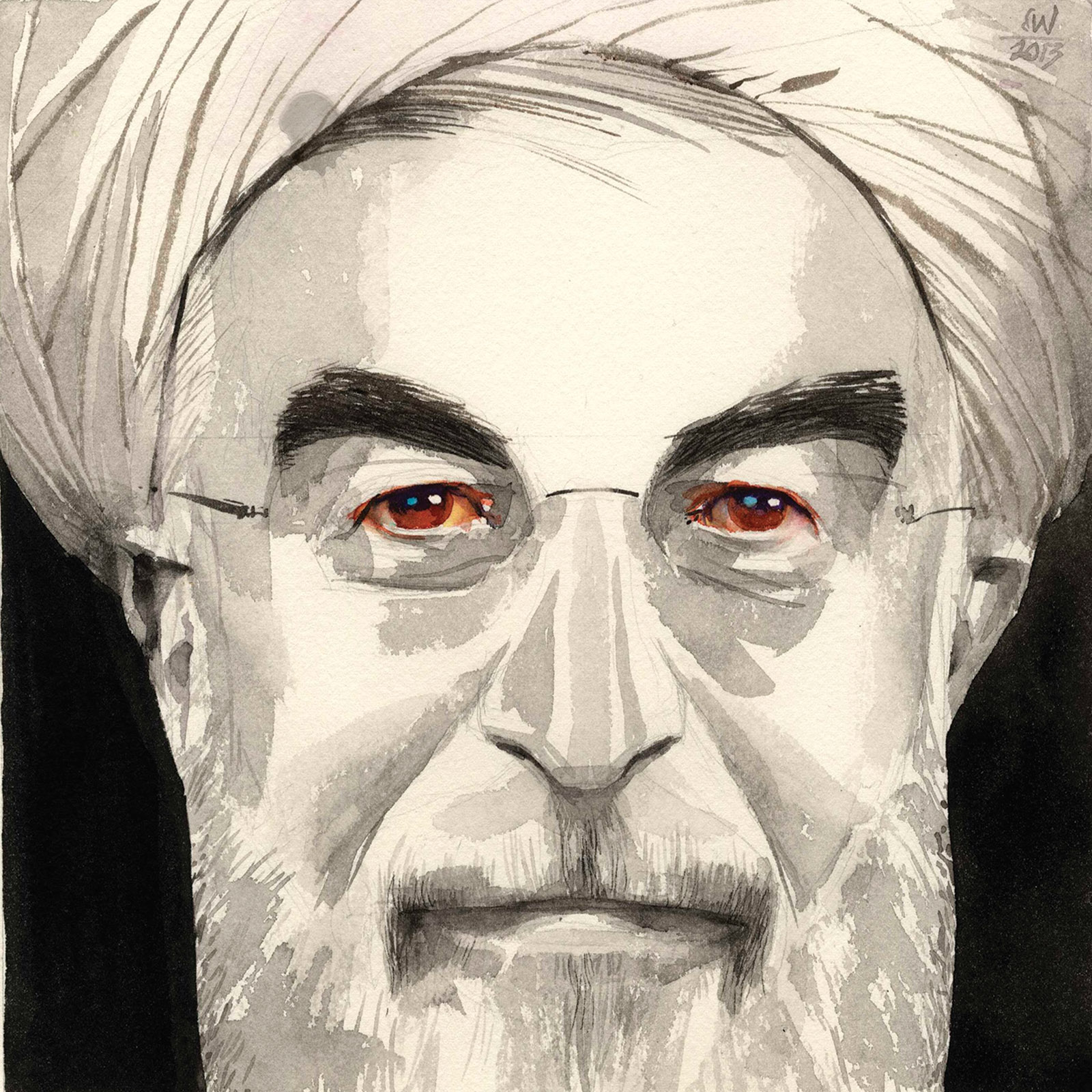

That the changes coursing through Iranian society cannot be stopped, but may possibly be channeled, is something President Hassan Rouhani understands. A tough, canny mullah who has occupied senior posts since the beginning of the Islamic Republic and has become a reformer, he kept his counsel during the brutal crackdown after the 2009 election. This time silence was not an option; his government was the initial target of the protesters, and calls of “Death to Rouhani!” were heard. But the president did not respond by reviling or threatening his detractors (in contrast with Ahmadinejad, who called the protesters of 2009 “dust”). Instead he has gone out of his way to articulate many of their grievances, in the process advancing concepts so radical they amount to abandoning important revolutionary doctrines.

The Rouhani proposals can be boiled down to two points: an increase in institutional transparency and in personal freedom. The Islamic Republic as represented by the supreme leader is hostile to both. Since the protests, the president has promised greater scrutiny of publicly funded clerical institutions—including one that pays a dole to unemployed mullahs, and others that spread Islamic propaganda—whose reluctance to open their accounts has been much criticized. He has also denounced the use of surveillance devices by the security services, the practice of investigating the religious and political beliefs of applicants for jobs in the public sector, and crackdowns on the Internet. (The messaging app Telegram, with 40 million Iranian subscribers, was blocked for more than two weeks during the protests on the orders of the Supreme National Security Council, which is controlled by conservatives. On January 13 the authorities ended the block, which many people had sidestepped by using virtual private networks, VPNs, to access sites banned on the public network.)

In perhaps his most perceptive comments, on January 8 President Rouhani summed up the division that has opened up between the clerical establishment and the young when he said, “The problem is that we want people two generations younger than us to live the same way we like to live, while in reality we can’t…prescribe their lifestyle.”

Lifestyles in the Islamic Republic have changed more in the last ten years than in the previous thirty, but the desire for further and faster change is insatiable, and the president is a regime loyalist who realizes that unless the reformists within the government adopt more radical objectives, the rift between the people and the system will become impossible to bridge. At present nothing unites the vocal opposition, such as it is, except a visceral antipathy to the Islamic Republic and the clerical elite. During the protests, nationalist and monarchist slogans were hurled, as well as calls for human rights and an end to institutionalized corruption. But no one really expects serious agitation in favor of the return of the Pahlavis (the shah’s son lives in the United States), while the socialist ideas that animated many of the revolutionaries in 1979 have given way to equally unattainable dreams of consumer heaven.

Advertisement

No adventurous changes of the kind favored by Rouhani will be achievable as long as the frail, seventy-eight-year-old Khamenei retains control of his faculties and the country, but the sixty-nine-year-old president is clearly demonstrating his intention to have reformist ideas dominate the next phase of Iranian history. Rouhani would argue that his aim, as a loyalist, is to protect the Islamic Republic, but history is full of reformists who have accidentally opened the door to political collapse. If there is one moniker no Iranian leader covets, whether he is a reformist or a hard-liner, it is “Iran’s Gorbachev.”

If the death of Iran’s supreme leader will be, as a friend of mine puts it, Iran’s second ground zero (the first being the shah’s flight in 1979), avoiding turbulence even in the interim won’t be easy. The nuclear deal of 2015 and the lifting of nuclear-related sanctions were supposed to lead to rising prosperity, but the country’s successful return to the international oil markets has been more than offset by low prices and the continuing unwillingness of European firms to do business with it. (US companies are mostly barred from Iran as a result of bilateral sanctions that are separate from the nuclear issue.) Trump’s hostility to the Islamic Republic and his support of Saudi Arabia and Israel have sharpened the fears of European companies that the US will punish them if they enter Iran, so on the whole they have refrained from making substantial investments in the world’s last unexploited market (not counting North Korea). One Iranian food manufacturer I met reported that his efforts at forming a joint venture with a big Italian company had come to naught because of worries about US retaliation: “After eighteen months of talks they simply walked away.”

Contrary to what Trump and his allies allege, Iran is far from awash in post-sanctions loot; the country’s oil revenues in 2016 (around $41 billion) were $20 billion less than those in 2013, when sanctions were at their peak. Under Rouhani’s frugal stewardship, inflation has fallen, and last year the economy grew by around 6 percent. No one is starving in Iran, and people have some money for consumer goods—imports of rice, which is associated with fine living, are up sharply, and Saeed Laylaz, an economist, reports that some 600,000 poor Iranians were able to buy cars over the last Iranian year. (The Iranian year begins near the vernal equinox.)

Yet there is a dangerous gap between popular expectations of a better standard of living after the nuclear deal and the way things have turned out. Half the country’s population is under thirty, and with all the demands that Iranians regard as their right—car, house, and family—the pressure to increase the number of jobs is immense. But those being created are mostly unskilled; there are fewer opportunities for university-educated Iranians, many of whom end up unemployed or doing work for which they are overqualified. In some of the small towns where the recent protests took place, youth unemployment is even higher than the national figure of 24 percent. And even if international relations improve, foreigners would not rush to invest in Iran unless Iranians do so themselves.

This isn’t happening. The government is spending its revenues on salaries, with little left over. As for the private sector, in a country where illegal credit institutions (affiliated with groups such as the Revolutionary Guards) offer 24 percent interest—called “profit” in the jargon of Islamic banks, which are forbidden to pay interest—entrepreneurs have little reason to invest in the real economy. Across the country industrial plants are operating at reduced capacity because their owners, many of them the recipients of loans under Ahmadinejad, have put the money on deposit, or into property, or offshore. Pay in arrears is a fact of life for workers in both the public and private sectors.

The controversial credit institutions account for around a quarter of all banking activity. They are allegedly used to launder money from drug, fuel, and alcohol smuggling, and—as all pyramid schemes do—collapse spectacularly when the base thins out. “I didn’t see a single rial,” lamented a depositor who recently lost his life savings this way, “and when I went [to the premises] I was told that the general manager was in jail.” The government would like to fold the credit institutions into the mainstream banking system, but the banks are themselves in poor shape, saddled with bad loans given out under duress during the Ahmadinejad period. As borrowers struggle to repay these loans, the amount of debt on the banks’ books continues to rise—by a quarter over the last Iranian year alone.

Much money is being spent to assuage public anger. The Central Bank has reportedly paid out large sums to people who sank their savings in the credit institutions. The government is propping up seventeen public pension funds that the minister of social welfare has declared “bankrupt”; the sight of desultory bands of pensioners raising their fists outside government buildings has become common. Fear of a popular reaction will probably lead parliament to water down Rouhani’s plans to raise gas prices and cut subsidies. If he is serious about balancing the books, many people argue, he should concentrate his efforts on the thieves and fat cats who made millions when the nation’s fortunes were at their lowest.

It is widely acknowledged that under Ahmadinejad well-placed officials and senior Revolutionary Guardsmen enriched themselves through sanctions-busting, hoarding, and speculation, and in 2016 the businessman Babak Zanjani was sentenced to death for skimming billions of dollars from illicit oil sales. (His sentence has yet to be carried out.) Rouhani and his allies have a particular interest in demonstrating that the economy was in ruins when they took over and that the country’s structural problems date from Ahmadinejad’s time. This is largely true, but the former president is now presenting himself as a victim of plotting by members of the establishment, and to make his point he has picked a fight with the head of the judiciary, Sadegh Larijani, and other members of the influential Larijani family; both sides accuse the other of larceny and abuses of power. The state is now substantially weakened by quarreling between different power centers.

Last year, Ahmadinejad’s former vice-president Hamid Baghaei announced on Telegram that he had been sentenced to sixty-three years in jail for corruption. The state prosecutor has accused certain high-ranking officials of smuggling, and another former high-ranking official was convicted of being an accessory to murder. Rouhani’s brother, several senior Revolutionary Guard officers, and the brother of the vice-president have been added to a lengthening list of prominent people arrested on suspicion of corruption. In December the son of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani—a titan of the state who died in January 2017 after holding almost all the top positions in Iran—disclosed that his father’s body had contained suspiciously high levels of radioactivity and that the investigation into his death was being reopened.

“Nothing is in its correct place anymore!” exclaims a woman from the pressured, precarious middle class, citing almost at random a dearth of autumn plums (they were apparently exported to neighboring Iraq), the corruption of public examinations for university admissions, and a scandal surrounding canned food that was found to contain traces of cat meat. Add to this the driest, warmest winter in decades, nauseating pollution in the big cities, and a series of earthquakes—the worst of which, on November 12, took 620 lives in the west of the country—and it’s hardly surprising that people are jumpy.

They are also hooked on social media, which is no more trustworthy or temperate in Iran than elsewhere. A particular irritant to the authorities is the Amad channel, a dissident news service run from Turkey, which has been described to me as containing a mixture of truth, falsehood, and innuendo. It had 1.3 million Iranian followers on Telegram, but under pressure from Iran, Telegram closed down the channel after it issued calls for protesters to arm themselves with Molotov cocktails. The reluctance of many Iranians to join the protests stems in part from their suspicion that Amad and other opposition voices are supported by hostile powers. The BBC’s Persian-language channel, for instance, which reported extensively on the protests, is funded by the British government.

Still, many Iranians expressed derision on social media when the judiciary announced that the two detained protesters who died in custody had committed suicide, and that a third, a restaurant delivery boy who turned up dead in the western town of Sanandaj, was a terrorist. A claim by the national prosecutor that bullets found in the bodies of the dead protesters were not the kind used by the security forces seemed designed to back up Khamenei’s assertions that foreign powers and an exiled armed opposition group called the People’s Mujahedin had fomented the unrest. Again, Telegram was the forum for public skepticism, underlining the risks involved in permitting Iranians to use what has become an indispensable technology that can also be a conduit for popular wrath.

Iranian officials will be especially keen to prevent the so-far sedentary majority from being infuriated by further deaths, whether in custody or on the streets, which could rally them—despite all they have to lose—to the cause of opposition. It’s another lesson from 1978, when isolated protests joined up and became an uninterrupted train of death and mourning, and the revolution got closer.

Great upheavals can start with trifles, like the confiscation of the street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi’s wares in the small Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid in December 2010, which set off the Arab Spring. Or they can start with falsehoods, as when the revolutionary forces blamed the shah’s government for the inferno that killed at least 470 people in a cinema in southern Iran in 1978. (A tribunal that was convened after the revolution determined that in fact Islamic radicals had been responsible.) In Iran today, with all sides making outlandish and in many cases unverifiable claims, it is often hard to separate truth from lies. “Do not believe any assertion if you have not seen…proper documentation,” Ayatollah Khamenei warned on January 9. On the same day hitherto unseen footage was mysteriously disseminated on the Internet showing the moment when Khamenei was elevated to the supreme leadership in 1989, under circumstances that his detractors are now calling unconstitutional.

On January 9 Khamenei also blamed America, Israel, and (indirectly) Saudi Arabia for stirring up the protests. He delivered an implicit rebuke to Rouhani when he said that the “revolutionary youth,” far from feeling alienated, are “more numerous now than they were at the beginning of the revolution.” Of all Trump’s messages during the protests, none seems to have riled the supreme leader more than his tweet that “other than the vast military power of the United States…Iran’s people are what their leaders fear the most.” Khamenei responded furiously that “the Iranian regime was born of these people…if we were so scared of you, how come we tossed you out of Iran in the 1970s, and out of the whole region in the 2010s?”

His words were a reminder that no matter how parlous things are at home, Iran’s international influence has rarely been higher. And while Iranians frequently call on their leaders to focus on domestic challenges, Iran’s striking success so far in preventing ISIS and other Sunni militant groups from destabilizing the country can at least partly be attributed to its strategy of propping up allies like Syria’s president Bashar al-Assad and the Shia militias of Iraq. However much liberal Iranians I know disapprove of the Revolutionary Guard’s political and economic interests, they confess privately that they are glad to have such a formidable force to protect them.

Although on January 12 Trump reluctantly waived sanctions on Iran for another four months, keeping the nuclear deal barely alive, Iran’s leaders are convinced that the United States, having been silent on the matter of regime change under Obama, is once again committed to toppling the Islamic Republic. Whether or not Trump carries out his promise to either “fix” the deal or tear it up (given Iran’s refusal to discuss amendments, no fix seems possible), Iran’s internal struggle for democracy has once again been linked to the strategies and whims of the country’s external enemies.

—January 25, 2018

This Issue

February 22, 2018

God’s Own Music

The Heart of Conrad

Doing the New York Hustle