In the early morning hours of September 4, 1963, a family was asleep in a yalı, or wooden house, near the shore of the Bosphorus. Fog sometimes twists so completely around the waters of Istanbul that from the hillsides of the European quarter the Old City disappears. From a perch on the Asian side it can seem as if there is no Europe at all. That was why, on that morning, a 5,500-ton Soviet freighter hauling Nikita Khrushchev’s military supplies to Cuba rammed thirty feet inland, straight inside the yalı of the sleeping family. “We thought the yalı had been struck by lightning; the building had split in two,” a family member told the newspapers. “When we pulled ourselves together, we went into our third-floor sitting room and found ourselves nose to nose with a huge tanker.” Two yalıs were crushed, and three people died. Orhan Pamuk recounts this event in his 2003 memoir Istanbul: Memories and the City. The newspapers that reported it, he writes, featured a picture of the tanker in the sitting room: “Hanging on the wall was a photograph of their pasha grandfather; sitting on the sideboard was a bowl of grapes.”

The story is one of many tanker tragedies described in Pamuk’s chapter “On the Ships That Passed Through the Bosphorus…and Other Disasters.” There was the Yugoslavian tanker Peter Zoranich carrying heating oil that exploded when it smashed into the Greek vessel World Harmony; the Romanian tanker that split a fishing boat in two; another that collided with a Greek freighter and exploded violently enough to shatter windows many miles away; and the Lebanese shipload of Romanian sheep that tangled with a Filipino cargo vessel carrying wheat from New Orleans to Russia. Twenty thousand sheep ended up at the bottom of the Bosphorus, though a few swam to shore, surprising some men drinking coffee.

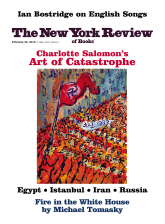

I don’t know why the Romanians and the Greeks had such bad luck on the Bosphorus in the twentieth century. But it is hard to read this chapter—the book has been reissued this year in a gorgeously illustrated special edition—and not think that these historical calamities, these drowned sheep, could easily be invoked to justify Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s plans to build an entirely new canal parallel to that beautiful, boat-clogged strait. Erdoğan’s dream of a second Bosphorus is most commonly called, even by himself, “the Crazy Project.”

The idea, which Erdoğan’s government has been fantasizing about for over six years now, is a canal that would extend from the Sea of Marmara to the Black Sea, much as the Bosphorus does. It would be around thirty miles long, twenty-seven yards deep, and anywhere between 120 to 160 yards wide (estimates vary), and would eliminate tanker traffic from the Bosphorus entirely. The government argues that the 50,000 ships passing through the strait every year, including some 5,000 that carry hazardous chemicals, are endangering its citizens, as shown by the many stories in Pamuk’s book. “More than seven hundred accidents occurred in the Istanbul and [Dardanelles] Straits in [the] last fifty years,” Captain Saim Oğuzülgen, director of the Turkish Straits Research and Implementation Center at Bahçeşehir University, told a Turkish newspaper some years ago. The Crazy Project almost makes sense.

But many experts have warned of the environmental catastrophes the project could cause. A new canal would fundamentally transform the flow of the currents from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara, changing the salinity of both and affecting the disposal of urban waste. The project might also destroy farmland and forests on the outskirts of tree-deprived Istanbul; set off a development boom along the canal, including houses, office parks, malls, and roads; and affect the many lakes from which the city obtains its drinking water.

Environmental concerns in Turkey—after a decade of overdevelopment that has involved the uprooting of tens of thousands of trees and the pouring of what must be tens of thousands of tons of cement—have lately taken on grave proportions. This past July, for instance, an extraordinary hailstorm suddenly overtook the city. In a year of many disasters, both violent and political, none for me was more frightening than the instant blackening of a hot summer afternoon and the sky’s subsequent pelting of hail larger than golf balls. They took the paint and plaster off houses, shattered window panes, drove perfectly round holes into hard plastic bins, and knocked people in the head. This extreme weather event, many said afterward, seemed to come from Istanbul’s particular environmental problems.

Many Turksa also think there is no way that their mysteriously resilient economy can support a megaproject like Erdoğan’s second Bosphorus, which is estimated to cost $10 billion. But late last year, after dignitaries from the president’s Justice and Development Party visited Panama to consult canal experts, Erdoğan announced definitively that the ground-breaking for the canal would happen in 2018.

Advertisement

As Pamuk describes throughout his book, such promises of modernization characterized much of the twentieth century in Turkey. Politicians of all persuasions—leftist and nationalist descendants of Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, and especially the center-right politicians who were Erdoğan’s precursors—promoted development as proof of their competence. After World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Atatürk and his soldiers fought off the advances of Western forces determined to claim Istanbul and much of the Aegean coast for themselves. These Kemalists then had to engage Turkish citizens in the patriotic project of building a modern nation out of the rubble of a ravaged former empire. By the 1980s, secularist generals were encouraging Turkish politicians to open up markets and accelerate industrialization. As early as 1994, Bülent Ecevit, a longtime leftist nationalist politician who came of age during a comparatively impoverished era, included the idea of a crazy canal in his political platform. Turkey after World War I was terribly poor, and ordinary citizens relished modernization, the illusion of catching up with the West.

Pamuk deplored “the neglect and dereliction” that accompanied these efforts. In the tearing down of pashas’ mansions, and in the deliberate burning of the ornately beautiful wooden yalıs in order to build ugly modern apartment buildings, he saw that “the great drive to westernize amounted mostly to the erasure of the past.”

I read Istanbul before I moved to the city in 2007, the year that Erdoğan, then supported by liberals, began his triumph over the military. There was a brief, golden period of optimism about the former Islamist, but even then his government had begun manipulating the judiciary, imprisoning opponents, and rigging the country’s privatization process so that it favored businessmen close to the state. Back then, Erdoğan received a good amount of sympathy, especially from Westerners, and I wonder if Pamuk’s books had something to do with that: the Nobel Prize winner’s criticisms of the Turkish Republic seemed in some way to match Erdoğan’s rejection of it.

Perhaps the rush to erase a civilization had, indeed, been a crime against Turkey’s deeper Ottoman cultural roots, and perhaps it was not wrong, or at least not surprising, that eventually a leader would try to restore what was lost in the country’s unrestrained efforts to emulate the West. The irony is that Erdoğan became the most egregious modernizer of all. But here lies the confusion about Turkish modernization and Westernization, and about Turkish Islam and secularism: all of these concepts have become so distorted and inaccurate that it is difficult to discern what actually happened to Turks in the twentieth century.

Both Pamuk’s book and a new history, Istanbul: A Tale of Three Cities by Bettany Hughes, make it clear that part of the reason for this distortion is that the country is so rarely described from within. Hughes, like many who have written about Istanbul, is a foreigner, and thus prone to the familiar hyperbole about the glories of the premodern city. Pamuk, meanwhile, devotes much of his book to addressing foreigners’ perceptions of his native city, and admits he is obsessed with how Westerners see it. These discussions can have the effect of keeping one very far from the actual streets of Istanbul.

But much of Pamuk’s book is also dark and intimate, and not at all like foreigners’ accounts, which so often wallow in the city’s exotic beauty. In 2017, his memoir of love does not read like urban hagiography but instead like a story of disintegration. When we remove our fantasy-inflected perceptions, what is left of historic Istanbul? What was this great civilization that Pamuk would say the modern-day Turks were “unfit or unprepared to inherit,” and what did they do to it?

Hughes, a classicist, is the author of Helen of Troy: Goddess, Princess, Whore and The Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens and the Search for the Good Life. The ancient and Roman periods, not surprisingly, dominate more than half of her six-hundred-page biography of Istanbul. The Ottoman Empire gets about two hundred pages—Suleiman the Magnificent is given a few sad paragraphs in which he manages to be overshadowed by both the admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa and the architect Mimar Sinan—and Istanbul’s tragic, multitudinous twentieth century is, proportionately, accorded much less. But Hughes’s proclivities also mean that the book is cleverly organized around descriptions of various artifacts from Roman times that have been uncovered in the recent digging for one of Erdoğan’s megaprojects, the underwater tunnel across the Bosphorus connecting Asia to Europe.

Advertisement

Hughes uses these artifacts to connect the Roman Era to the Reis Era (reis is the Turkish word for chief, and Erdoğan’s nickname). “A coffin might seem an odd place to start,” she writes early on in the book, about the world’s oldest coffin, which was found in 2011 under a new metro station near Istanbul’s red light district. Inside lay a woman curled in the fetal position. In a neighborhood on the Asian shores of the Bosphorus, we discover remnants of scuta, the leather shields of Roman soldiers, which may have given the area its name—Scutari—before it became Üsküdar, where Erdoğan now keeps one of his homes.

Hughes’s history begins in the seventh century BC, when Megarian Greek explorers settled the land across from ancient Chalcedon, or “the city of the blind”—so named for the sad people who settled the Asian side of Istanbul rather than the obviously superior hills of the western side. After that came the Achaemenid Empire and years of violent conflict over the city among Greeks, Persians, and Macedonians, until Alexander the Great swept over the Hellespont and liberated Byzantion as an independent Hellenic entity.

The city gained a special status in the expanding Roman Empire, and in 330 AD, Constantine I declared the city—now renamed Constantinople—the empire’s capital. As the surrounding regions gradually converted to Christianity, Hughes writes, the religion “was looking increasingly like a means to unify and indeed to consolidate power.” Constantine considered Constantinople a city given to him by God.

Over the next centuries, the Eastern Roman—later called the Byzantine—Empire was weakened by repeated attacks from Goths, Huns, Vikings, Vandals, and, much later, those tiresome Crusaders. A new Muslim army of Turks had by the time of the Crusades captured much of Syria, Iraq, and Anatolia, and threatened to conquer Constantinople and breach the gates of the Christian world (as Muhammad had allegedly dreamed). The Byzantines and Turks clashed most dramatically in 1017 at the Battle of Manzikert, which Erdoğan regularly invokes to stir up neo-Ottoman nostalgia and nationalism.

By 1326, the Ottoman leader Orhan Gazi and his people had settled a hundred miles southeast of Constantinople, in Bursa. Orhan’s father, Osman, told him he dreamed that a “tree grew from his navel.” The tree “spread across the earth, and when a wind stirred its sword-shaped leaves these pointed towards the city of Constantinople.” Osman at the time had recently had his heart broken by a girl from Eskişehir. “It was this acceptance of grief and sorrow as a certainty of the human condition that liberated Osman to achieve greatness,” Hughes writes. The idealization of Istanbul, and its history of chauvinism, begins with this tribesman. Here is how Ottoman myths came to characterize Osman’s dream:

That city, placed at the junction of two seas and two continents, seemed like a diamond set between two sapphires and two emeralds, to form the most precious stone in a ring of universal empire.

Osman thought that he was in the act of placing that visioned ring on his finger, when he awoke.

This dream would be realized in 1453, when the Ottoman sultan Mehmet the Conqueror launched a well-organized attack on Constantinople that lasted fifty-one days. Four thousand people were killed, many were raped, and countless treasures, buildings, and books were destroyed. Mehmet reportedly wept when he finally took stock of the devastation his troops had wrought. The Turks, who communicated with their conquered subjects in Greek, had been meticulously planning the empire that would last for the next five hundred years.

From the fifteenth century onward, Constantinople—Konstaniyye to Muslims, as ISIS propaganda never fails to remind us—was a wondrous place, heavily wooded and full of “cherry, almond, pear, plum, quince, peach and apple trees,” as well as bounteous animal and marine life. The Ottomans saw nature as a sign of wealth and power. “Gardens were fundamental in the culture of Muslim Constantinople,” Hughes writes. Western visitors identified one thousand gardens in the city, and one hundred imperial gardens around the palaces cared for by 20,000 gardeners. The city’s Muslim inhabitants saw the garden design around the Sublime Porte as, in Hughes’s words, “an outward sign of the harmony of justice, of the magnificence of the Ottoman dynasty.” Sultan Ahmed III in the eighteenth century began enlisting tortoises adorned with candles to illuminate the thousands of tulips planted between the pathways. The Ottomans loved nature, trees, flowers, and beautiful women from the Caucasus; they also loved books, knowledge, art, and fireworks displays. No wonder the many Western travelers who came to gaze at Constantinople record it as a land of fantasy.

The Ottomans were also relatively tolerant of non-Muslims, but Hughes never really contemplates why this was so. Nor does she elaborate much on the millet system, in which non-Muslims won the protection of the Ottoman state and could more or less govern themselves in certain matters of law and education according to their own religious strictures—as long as they accepted lower status and fewer rights. This absence of deeper discussion about religious tolerance becomes striking as, in the course of the history she tells, minorities in the empire begin to suffer more and more. Ottoman violence against Christians appalled Westerners after the early-nineteenth-century Chios Massacre, during which the Turks murdered countless Greeks on an island in the Aegean. Western eyes that had once been drawn to the Ottoman Empire with fascination now looked upon it with revulsion. The Russians soon tried to retake the capital of Christendom. Western bankers exploited Turkish debts. The hatred of the Turk spread to the United States, where newspaper editorials soon excoriated the Ottomans and clamored for their downfall.

Although she skates over this history rather quickly, Hughes has a gift for collapsing detail gracefully. We learn that the name “Golden Horn” (an inlet of the Bosphorus) comes from the glistening fish in its waters; that the star and crescent on the Turkish flag come from Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft; that the book review was invented in Constantinople; that the word “booze” comes from boza, a Turkish alcoholic drink; that the word “passport” came from the Sublime Porte; and that when the Ottoman Empire fell in 1922, the palace eunuchs formed a self-help group. But by the end of the book we are left mostly with these winning facts and Hughes’s romantic and laudatory words about Istanbul, the typical reflex of writers and historians who wish to suggest that Istanbul’s natural magic is ineffable and eternal.

When Pamuk read Joseph Brodsky’s offensive descriptions of Istanbul in The New Yorker in the 1980s—“nothing grows here except mustaches” is one terrible line—he felt both anger and relief. “When western observers speak ill of the city,” Pamuk writes, “I often find myself in agreement, taking more pleasure in their cold-blooded candor than in the condescending admiration of Pierre Loti, forever going on about Istanbul’s beauty, strangeness, and wondrous uniqueness.” Brodsky saw the Istanbul Pamuk himself had been seeing, a city that had become “a monotonous monolingual town in black and white.” To Pamuk, walking through the backstreets of Beyoğlu in the 1970s, Istanbul was “terribly poor and shabby,” besieged by a poverty that inflicted “heartache on all who live among” it. Pamuk famously called this hüzün. The empire had fallen and so had its grandeur and greatness; there were no more colors, no more languages, no more diversity—no more Christian-Muslim-Jewish cosmopolitanism of the Ottoman kind.

What remained, though, was the cosmopolitanism and cultural complexity of the Turks themselves. The incredible regional and ethnic variations they exhibited would take years for a foreigner to detect. Atatürk and the Kemalists wanted to conceal this diversity for the sake of unifying Turkish citizens under a common culture. Pamuk makes it clear in Istanbul, and even clearer in his 2014 novel A Strangeness in My Mind, that he is less interested in explaining Turkey to the West than in reconstructing a particular period in Turkish history. In the details of the novel—and of all his books, as well as his Museum of Innocence, which assembles scores of old products and artifacts from recent Turkish history—he displays an obsession with setting things down before they are swept away. “History,” he writes, became “a word with no meaning.” The reason Pamuk liked Brodsky’s writing was because Brodsky acknowledged that Istanbul was not a divine, indestructible city at all. It was a city to which something terrible was happening.

One of Pamuk’s more controversial preoccupations in Istanbul is that the repression of Islamic culture also involved repressing, or blighting, the Turkish soul. The secularized people he knew, he writes, grappled “with the most basic questions of existence.” But reading the memoir in its new edition, with Hughes’s descriptions of Istanbul’s beauty in mind, I was more keenly aware than I had been before of Pamuk’s reports of the city’s physical destruction—the tankers crashing into yalıs that modernizing Turks no longer loved or wanted, the popular Turkish pastime of watching the demolition, by fire, of historic buildings. His Istanbul was not necessarily a commentary on the wisdom of enforced secularization or on the benefits of religiosity. It could just be about the fact that human beings cannot withstand so much loss.

In this year’s somber Istanbul biennale, most of the exhibits concerned the environment, urbanization, and annihilation. At the Pera Museum, several paintings had been covered in cement. More than one exhibit featured people cowering in bunkers, and many more displayed themes of claustrophobia. An apartment was outfitted as a kind of beautiful haunted house throughout which Greek music—ostensibly that of its onetime inhabitants—played mournfully. Another exhibit invited several artists to draw the marine and plant life of Istanbul, as if to say: Some day they will all be gone. One installation forced visitors to stand in a room as apocalyptic biblical passages were projected on the floor and snaked around their feet. When I was there, a group of children chased after the words, trying to jump on them, to make them stop.

Since Ottoman times, as we learn from Hughes’s book, the earth has had a particular significance for Turks. “Even outside the poorest houses there were window boxes or a pot of herbs,” she writes. “Horticulture was meant to represent God’s bounty and the diversity of his creation.” She also notes that “during the First World War Western soldiers noted Turkish troops laying out little patches of turf and plant pots around their campaign tents.” It’s not surprising. When Turks migrated to the cities from Anatolia with little but the shirts on their backs and were forced to build cheap shanty homes by hand, they nonetheless always tried to snag a garden plot in the big city.

Pamuk’s hüzün may have emerged in response not to the loss of empire, wealth, power, or Islamic culture, but to the loss of a civilization that loved nature and beauty and that treasured a city once thought to have an endless supply of both. In Byzantine times, after environmental catastrophes, Hughes writes, “there seems to have been a sense that God was somehow displeased by Christendom.” When that hailstorm struck Istanbul in 2017, the joke I heard was that God was displeased with Erdoğan.

Then again, the president is just following the path to progress, like the good disciple of Ecevit, Atatürk, and the Ottoman sultans he is. Someday the endless debate about Islam and secularism, tradition and modernity, will be subsumed by the one about environmental disaster. None of these questions about Istanbul as “the world’s desire” will matter if nothing of traditional Istanbul survives, if its inhabitants, once prevented from modernizing, continue to do so with such vengeance.

This Issue

February 22, 2018

God’s Own Music

The Heart of Conrad

Doing the New York Hustle