The finest diarists are able to view themselves with the detachment they apply to others. They become, in this sense, their own sharpest biographers, dividing themselves into both observer and observed, audience and performer, hovering eagle-eyed above themselves, ever curious to record, however unfavorably, their own imperfect ways. As Claire Tomalin puts it in her biography of Samuel Pepys: “In writing it down, he detached himself from the self who acted out the scene.”

In her diaries of her years at Vanity Fair, Tina Brown is certainly adept at noting, with her unforgiving eye, the flaws in others. Revulsion brings out the best in her. The Hollywood agent Swifty Lazar is “tiny and bald and hairy in the wrong places. From the back his bald head and ancient baby’s neck look like crinkled foreskin.” Nancy Reagan’s walker Jerry Zipkin possesses a face “like a huge inflated rubber dinghy, balanced on top of a short, Humpty-Dumpty body.” A social columnist at The New York Times is “a bogus grandee…a coiffed asparagus.” Jackie Onassis’s face is “always slightly out of whack with her expression, as if they are two separate entities at work. She has perfected a fascinated stare.”

Brown also has an ear finely tuned to the absurdities of the rich, the spoiled, and the famous. She records them with relish. “You know what?” Donald Trump shouts to her over dinner at Ann Getty’s in 1987. “Went to the opening of the Met last night. Ring Cycle. Plácido Domingo. Five hours. Dinner started at twelve. Beat that. I said to Ivana, what, are you crazy? Never again.” Minutes later, an unnamed Italian art dealer shares his misgivings about the American way of life:

You know,…it is easy in America to take a very tiny sum like five hundred thousand dollars and turn it into three hundred million! So easy! But you know what? I don’t want to. Because eet means raping those poor fuckers the American public even more than they are already. You know what ees the difference between the European peasant and the American peasant? The American peasant eats sheet, wears sheet, watches sheet on TV, looks out of his window at sheet! How can we go on raping them and giving them more sheet to buy!

In moments like these, Tina Brown is the social diarist par excellence, skewering the pampered society grotesques of her time with a gleeful and merciless zest. “To be a good diarist one must have a snouty, sneaky mind,” wrote Harold Nicolson in his 1947 diary, and Brown is clearly in possession of Nicolson’s prerequisite. She snuffles around like a prize truffle hog, unearthing all the whiffiest gobbets of conversation. Her pocket-sized sketches have the cruel precision of caricatures by Gillray or Rowlandson and the comic verve of Edith Wharton. “We had lunch with the preposterous Princess Michael of Kent,” she observes at one point,

who looked about fifteen hands high in an orange silk wrap dress. She has developed a mad, false laugh and a new Lady Bracknell voice for dealing with inferiors. “Row-eena,” she gushed at the cowed debutante she totes around as her “lady-in-waiting,” “where is the Dom Perignon? It was sitting outside but those fooools have taken it away! Find it! (Mad false laugh.) “Isn’t the service quite diabolical? Do shut the kitchen door, Rowena. I hate to stare into a kitchen!”

Brown chronicles a world of fashion designers and film stars, perfumiers and politicians, each category barely distinguishable from the others. She particularly thrives on the fury caused by injured vanity: Oscar de la Renta is furious with Bob Colacello for suggesting that Geoffrey Beene’s business is bigger than his. (“His business is not twenty times bigger than mine! Mine is twenty times bigger than his….When I see that cheap little nobody Bob Colacello he better get out of my path because I will knock him down.”) The owner of Sotheby’s is furious that “the wife of a New York auction house chief” has been identified in Vanity Fair as a former Madame Claude girl. (“Are you aware how few auction house chiefs there are?… Do you think anyone thinks it’s Mrs. Alsop of Christie’s?”) Such contretemps suggest that little has changed since Dorothy Parker first observed, “To see what God thinks of money, just look at all the people he gave it to.”

More often than not, though, Brown’s jibes are too generalized, too hand-me-down, to draw blood. Take her anthropomorphization of noses, for instance: at first, it’s amusing to learn that Norman Podhoretz has a “hard, pitiless nose” and that Stephen Spender has “wonderfully malicious nostrils.” But she employs these preassembled constructions again and again, with diminishing returns. After Carl Icahn’s “big, humorless nose” and Warren Beatty’s “unserious nose,” the joke wears thin, its meaninglessness exposed by repetition.

Advertisement

Brown spares herself the cynicism she accords others. In her babyishly boastful introduction, she excitedly tells the story of her own life as though she were narrating the trailer for her own biopic: “I was swept off my feet in sophomore year by Martin Amis, then a twenty-three-year-old literary lothario.” An article she wrote for the Oxford student magazine apparently “launched me as an enfant terrible of the British media,” though this is the first the British media will have heard of it. Her gooey account of her first encounter with her husband, then Sunday Times editor Harold Evans, might have come straight out of Fifty Shades of Grey: “The fact that the mighty Mr. E had read my insignificant jottings…and actually wanted to meet me was, to me, heart-stopping.” She is rarely backward in coming forward; even her humility carries a strong undercurrent of self-satisfaction, and she is deft at making breathless elisions between her own life and world events, as though the one were indistinguishable from the other. “The same month I took over the editorship of Tatler, in June 1979,” she observes, “a new Prime Minister took over 10 Downing Street.”

After a few years at Tatler, she was dreaming of Manhattan, where she had spent a three-month “sojourn” after graduating. “I wanted to go back to Manhattan—and conquer it,” she writes, now firmly the star of her own movie. As luck would have it, in the spring of 1983, she received a call from Alexander Liberman, the editorial director of Condé Nast, and “the strains of Gershwin’s clarinet again began to rise in my head.” At this point, his intentions were opaque, beyond a lunch meeting in Manhattan. But Brown already knew what she wanted. “A tortured, perilous courtship for the editorship of Vanity Fair was about to begin” is the way she ends her introduction.

The diaries begin on April 10, 1983, with our modern-day Becky Sharp landing in New York City late at night, “brimming with fear and insecurity.” As if by magic, both these emotions have disappeared by dawn. From then on, it’s down to business. “As soon as I woke up I rushed to the newsstand on the corner to look for the April issue of Vanity Fair.”

She does not like what she sees of the newly revived magazine, and judges that the “incomprehensible” cover will “surely tank on the newsstand.” Inside, there’s a “brainy but boring” essay by Helen Vendler, a poem by Amy Clampitt, and “a gassy run of pages from V.S. Naipaul’s autobiography.” As her diaries unfold, her weariness with the world of literature grows steadily more apparent. Of the handful of authors who merit a mention, Philip Roth is “a bit of a disappointment,” and Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne are “always a struggle.” Only Norman Mailer is really up to scratch, possibly because he represents yet another career opportunity: “I feel I want to write down everything that comes out of his mouth. He needs a Boswell to follow him around.”

In her first diary entry, Brown has already set her sights on the target closest to hand. The question is, how long can Richard Locke survive as Vanity Fair’s editor? By the end of the month, Locke has been replaced, not by Brown—she feels she ducked the offer, though it remains unclear whether it actually came—but by Leo Lerman from Vogue (“Leo is about a hundred years old”). Brown has been made a consultant, secretly believing that “there is no way Leo can do the VF job successfully.” The diary entry on her first day in her new advisory role includes what she calls a “killer critique” of Vanity Fair, which she has diligently copied out of that month’s New Criterion. “Now I understand why they wanted me here so fast,” she concludes.

However crablike her advance, it fails to pass unnoticed. Lerman “looks at me with awful suspicion, like a manic, whiskery prawn, convinced I am Alex’s spy.” Which, of course, she is. A month passes, during which Lerman rejects all her ideas. “Doesn’t he understand I could save his job?” she asks. But there’s no time for an answer. Before the completion of that day’s entry, she has buttonholed Condé Nast owner Si Newhouse—who scuttles in and out of these diaries like a goblin—and insisted to him that Lerman cannot provide leadership, and that she should be his replacement.

By the end of that year, her dream has come true. “Bull’s-eye! They were offering me the job!” Significant moments in her life may be measured out with exclamation marks. “The first issue of my VF is on the newsstands at last! I love the way it looks, sexy and strong and clean!” (March 31, 1984); “A red-letter day! Si called me upstairs to give me a thirty-thousand-dollar raise!” (December 14, 1987); “Vanity Fair’s fifth anniversary party! What a night!” (March 1, 1988); “Hooray! I love my job! I love Vanity Fair!” (January 5, 1989).

Advertisement

Accordingly, her first entry for 1990 begins: “A new decade!” After five years at Vanity Fair, her zeitgeist barometer has become supersensitive, quivering uncontrollably at each fresh event, her favorite adjectives—epic, iconic, turbo-charged, hot—applied to everything, no matter how inconsiderable or underwhelming. “It’s amazing how fast the eighties recedes in the back mirror,” she observes, and it’s still only January 10. After all, “Dynasty finally bit the dust at the end of last year, and it now feels as antique as ancient Rome.” By the following September, she has put Roseanne Barr on the cover because, apparently, “proletarian chic is all the rage.”

She who lives by the zeitgeist must die by the zeigeist. In its appetite for the new and modern, The Vanity Fair Diaries seems something of a period piece, full of trappings now almost as outdated as bustles, wing collars, and horse-drawn carriages. In 1986, Brown is having a drink at the Ritz-Carlton with a flirtatious Warren Beatty (“So your husband’s in Washington half the week?… How do we progress this now?”) when a waiter brings a telephone to the table. Two years later, Brown is proud to have coined the term “Acceleration Syndrome,” because “car phones and call waiting and home faxes are making everything so revved up.”

The pages are packed full with the relics of a bygone age—“the mega-rich Reliance Insurance tycoon Saul Steinberg and his trophy wife, a slim brunette bombshell called Gayfryd,” “Paul Marciano, the marketing wiz behind the Guess Jeans ads,” and so on, ad infinitum—mysteries to all but the most dedicated social antiquarian. At Vanity Fair’s fifth anniversary party, Brown ends the night conga-ing with Henry Kissinger, who would have been redolent of an earlier era even back then. The Kissingers were, as always, the first to arrive, along with Dennis Hopper and Jackie Collins. In Rupert Everett’s witty memoir, Vanished Years, the actor recalled a similarly lavish, similarly random party thrown by Brown and the then still-greetable Harvey Weinstein in 1999 to launch the epic, iconic, turbo-charged, hot Talk magazine. Everett arrived with Madonna, to find Kissinger already there:

Omygod, I think, this is the man who dragged Cambodia into the Vietnam War, but of course I say nothing, even when a waitress comes by to ask what we want to eat.

“What’s on the menu?” asks Kissinger, and I can barely restrain myself from shrieking, “What’s on the menu, Henry? Would that be Operation Menu?”

Instead I obsequiously offer to go and fetch some nibbles. With success comes compromise, and it’s amazingly easy to forget two million massacred Cambodians as one is passing around the cheese straws.

There is nothing nearly as nimble in The Vanity Fair Diaries, nothing as ambivalent or funny or close to life. Instead, Brown makes the parties she throws and attends sound more like meat-processing plants, with herself as a senior foreman, present simply to deal with the assembled bodies, clipboard and bolt-pistol at the ready. A beady kind of joylessness abounds. “This party is for a thousand careful Cinderellas,” wrote Everett, “and even if their coaches don’t turn to taxis at midnight, their serene fascinated faces revert to witches’ grimaces if the evening’s longevity exceeds by a minute the schedule prescribed by their publicist.”

Yet with her quiver of exclamation marks, Brown persists in portraying herself as the wide-eyed ingenue, even when she is taking an ax to her underlings. Perhaps the most chilling phrase in the diaries is “Gotta clean house.” Soon after being appointed editor of Vanity Fair, Brown hears that a production editor has been complaining behind her back about rushed deadlines. She is furious. The production editor attempts to appease her with praise, but it is too little, too late. Within a few weeks, she is out. “Got back from Florida refreshed and fired Linda Rice,” Brown writes. And then she adds, breezily, “Gotta clean house.” Little Orphan Annie has turned into Lizzie Borden, running amok with the ax: “A few days away made me determined to remove negative elements from the office.” More casualties follow. In one particularly frosty passage—strangely reminiscent of Armando Iannucci’s recent movie The Death of Stalin—Newhouse goads her by asking, “Do you have a problem with firing people, Tina? I wouldn’t have thought you did.”

“No,” I replied. “And I feel I should start firing a few who are making problems.”

“All at once or one by one?” I felt he was teasing me now.

“I will let you know,” I said.

I immediately went downstairs and kissed good-bye to Locke’s golden girl Moira Hodgson. She writes well but her resentful politesse has been getting on my nerves.

A large part of the book is taken up with office politics, presumably more interesting to those involved and their immediate family and friends than to the rest of us. Might it be of use as a manual for aspiring editors? Brown offers little nuggets of advice, not least eternal vigilance, but it is doubtful that the set formula she has worked out by July 1984—“Celeb cover to move the newsstand, juicy news narrative like Vicki Morgan, A-list literary piece, visual escapism, revealing political profile, fashion. If we nail each of these per issue it’s gonna work”—could be successfully transferred to any other magazine over thirty years later.

“Juicy news narrative” invariably involves the murder of and/or by someone extremely wealthy and/or glamorous. If there has been a shortage of well-heeled slaughter that month, then an untimely death must suffice. On June 17, 1986, Brown records the news that “Olivia Channon, the Guinness heiress and Oxford undergraduate, overdosed on heroin and died.” Bingo! Her excitement is palpable, though she is careful to cloak it in sympathy. (“Who let her down?”) Within a week, Brown has hotfooted it to Oxford, researcher and notebook at her side, busily attempting to “re-create her story” for Vanity Fair. As it happens, her article never appeared, a fact that passes unmentioned in the diaries, which are devoted to narratives of professional success, not personal failure.

Brown does not share Pepys’s ability to detach the diarist from the self; there is an element of personal PR in almost everything she writes. In one entry, Harold Evans makes what Brown calls “the cunning point” that “people believe what they see in print even if it happens to be in your own publication.” Acting on this advice, she starts introducing excited reports of Vanity Fair’s epic, iconic, turbo-charged, hot success into her editor’s letters. Any candor is largely restricted to people other than herself, many of them, like Leo Lerman, now safely dead and buried. But in one area of her own life she is remarkably frank.

By and large, the diary form follows the vicissitudes of life too closely for a shape or clear themes to emerge, but one way of reading The Vanity Fair Diaries is as the record of one woman’s gradual realization of her ever-increasing market value. In this, she is free with her facts and figures: when she takes over the editorship, she accepts a salary of $130,000. Within six months, her agent, Mort Janklow, tells her that she has been offered “in the region of 250K” for a novel. She has never written one before, but that is not the reason she hesitates: “The catch is, I have no time to write it.”

In under four years, her stock has risen high enough for Swifty Lazar to phone her with the question, “How does two million dollars sound to you?…that’s what I can get for a novel by you.” Four months later, Newhouse raises her salary by a further $100,000. But this is peanuts: within a year, she has hired a lawyer to up the stakes. “Thanks to Mort, five years in I am now paid six hundred thousand a year on a three-year contract with a million-dollar bonus at the end, plus my parents taken care of and no debt on our apartment.” That debt, with Newhouse, mentioned almost as an afterthought, had been for $300,000.

The decisiveness she brings to her job is less evident in her life beyond it. Throughout the diaries, she seesaws, to the point of tedium, between wanting to live in the US and wanting to live in England. One moment, she is mad about New York; the next, for London, and then it’s New York, and then it’s back to London. “My fascination with New York success is beginning to pall,” she writes on New Year’s Eve, 1985. “In fact, I realize more and more, I love New York City, period. London seems to get smaller and smaller to me,” she writes on May 7, 1986.

Her prose, too, whips restlessly back and forth across the Atlantic, often within the course of the same sentence. Rupert Everett neatly described it as “the hilarious compromise an English speaker arrives at with the American dialect.” At times, she reminds me of an escaped prisoner in a hammy B-movie, desperately hoping to pass herself off as a native abroad, having memorized a dodgy phrasebook. “Gotta get some movie-star covers and see what’s popping on the West Coast after so long holed up in long-knived Manhattan,” she writes on a plane to Los Angeles.

Hyperbole acts on her diaries like a virus. At one point, she describes the launch party for her husband’s book as being “so high powered the energy threatened to lift the lid off the restaurant.” Elsewhere, articles “explode,” glamour is “drop-dead,” and, come December, New York’s pace “hots up to a burning crescendo.” Meeting Michael Jackson, she judges him “a Mozartian kind of genius,” and does not stop there. “His gift, like that of anyone world-class, is fostered by lonely discipline, obliterating obsession, and the desperate drive for the extinction of ego by the gift itself.”

A pivotal word in her diaries is “buzz.” In July 1985, she rails against it: “I’m sick of people writing about the ‘buzz’ I ‘create’ with Vanity Fair…. They call it ‘buzz.’ I call it engagement. I feel a nagging sense this ‘buzz’ bullshit would not keep being said about a male editor.” But before long she has forgotten her high-minded objections; as the diary progresses, she begins sprinkling the word approvingly. “By week’s end the buzz on the new VF was deafening,” she writes in February 1991. “I expected some buzz, but not what is unfolding,” she observes the following July, after the naked and pregnant Demi Moore has appeared on the cover.

Buzz is what she does; the busy buzz of self-promotion—hers, her friends’ and her enemies’—is the background noise throughout these diaries. In 1986, someone called the Countess of Romanones telephones Brown from Acapulco following the death of the Duchess of Windsor. It is the countess’s duty to escort the duchess’s corpse to its final resting place in the shadow of Windsor Castle. She wants Vanity Fair to provide a free seat on the Concorde and to ask a top designer to supply her with a free funeral outfit. Brown relays this tale of avarice and insensitivity with her usual gusto. “Is there anyone left who is not hustling?” she asks. Sensibly, she does not look to herself for an answer.

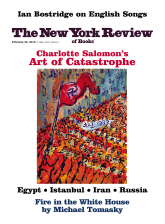

This Issue

February 22, 2018

God’s Own Music

The Heart of Conrad