Mr. Eady is a student concern specialist at North Charleston High, in Charleston, South Carolina. South Carolina was one of four states I visited to research—for my play Notes from the Field—what has come to be known, among social scientists, educators, jurists, politicians, and grassroots activists, as “the school-to-prison pipeline.” I met Eady when I took a side trip to Charleston while traveling up and down the “Corridor of Shame,” a stretch of towns along I-95 with about thirty-six substandard schools. Many children in these schools are travelers on the school-to-prison pipeline.

During the Obama administration the Justice Department released data revealing the overuse of expulsions and suspensions to discipline kids who live in poverty. Black, brown, Native American, and poor white children are disciplined more harshly than those in the middle and upper classes. If you are not in school, you are in trouble. Hence the schools themselves have been widely cited as the reasons why kids end up in juvenile facilities and from there begin cycles of incarceration. But schools are just one element in a series of problems that includes poverty, the drug economy, violence, mental illness, and our unrealistic expectation that the family as a social structure suffices as a protective antidote to all of the above.

If schools are to meet the demands of the modern world, they need to be more than sorting mechanisms designed to identify who goes to college, who joins the workforce after the twelfth grade, and those for whom there is no place. They need to be reimagined as centers for a culture of learning and growing in which students, teachers, staff, administrators, and parents are respected and cared for intellectually, physically, and creatively.

Tony Eady was about the 250th person I interviewed. He had worked in a maximum-security penitentiary before becoming a student concern specialist at North Charleston High. For Eady, students, teachers, and administrators in undersourced schools in poor neighborhoods are in as much of a pressure cooker as inmates and prison guards:

This job can be overbearing. This job can cause you to step outta your character…. Because I used to work in a penitentiary—I used to work at a maximum-security prison—I tell the kids; “This is just a rehearsal!” I tell the kids this: “When you get on that bus [to prison]—you get sentenced…you heading to one of those institutions, you have to change. You can’t be the same person you were when you walked into the courtroom…. You can’t be the same person because they are not normal people back there. Everybody is trying to get after you, or get over on you. It’s different…. It’s [words fail him here—he uses a gesture]. You have to step out of your character. There’s animals back there. People get raped, people get beat on, people get murdered, people get stabbed—there’s nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. This is real. And they buildin’ more of those than they buildin’ schools.”

The notorious Parchman Farm prison in Mississippi is about half a day’s ride north of where Jesmyn Ward’s characters live in her novel Sing, Unburied, Sing. It is the kind of place that would, to use Eady’s words, “cause you to step outta your character.” It has been chronicled in literature: in nonfiction books such as David M. Oshinsky’s riveting “Worse Than Slavery”1; in photographs, including those by R. Kim Rushing in his recent book Parchman, in which the images are accompanied by first-person, sometimes handwritten accounts from inmates2; in the blues and rock and roll; and in work songs such as those recorded by John and Alan Lomax, a number of which can be heard in the recent collection Parchman Farm: Photographs and Field Recordings: 1947–1959.3

Ward’s story is told by three narrators. Two—thirteen-year-old Jojo and his mother, Leonie—live in the present, and the third—a boy named Richie who is about the same age as Jojo—is a ghost. The novel opens in the words of Jojo on his thirteenth birthday: “I like to think I know what death is. I like to think that it’s something I could look at straight.”

Jojo, on paper, would seem to be the type of kid who might be sent to Mr. Eady’s office, if he lived in North Charleston. If he were evaluated—that is, if time and resources for evaluation were available—he might be categorized as “at risk.” His father, Michael, who is white and the son of rednecks, is incarcerated at Parchman. His mother, Leonie, a black woman, is by her own definition Michael’s “baby mama.” Leonie’s father, called Pop by Jojo, spent time at Parchman too, as a teenager. Jojo and his younger sister, Kayla, live with Leonie’s parents, Pop and Mam, as do Leonie and Michael when he is out of jail. Michael’s parents have nothing to do with their grandchildren, and on one occasion his father just about pulls a shotgun on Leonie when she drives onto his property to let him know his son is being released from prison.

Advertisement

It seems as if Jojo is not paying attention in school. But he is. He is incredibly vigilant. He sees through his teacher’s makeup to the bruises under her eyes and wonders if she gets beaten like his mother does. Leonie and Michael often fight. Jojo watches his mother get bruises.

In the real world, a thirteen-year-old with Jojo’s profile might have an IEP: an “individualized education plan.” The IEP would record everything about him, including information about his family. Of interest would be the fact that Leonie gets high often. She disappears for days at a time. What drug Leonie prefers is not explicitly stated, but she gets high with Misty, who likes Lortab, OxyContin, coke, ecstasy, and meth. Misty is white. Her boyfriend, Bishop, is also at Parchman. All of the adults around Jojo are connected to the system of mass incarceration. Misty, like Leonie, dates across racial lines. Bishop is black. Cross-racial dating is not unusual in the world of this novel; but the previous generation’s racism, like that of Michael’s parents, has not budged.

Leonie is not attentive toward her children. Her daughter, Kayla (short for Michaela, after her father), a toddler, is not yet completely verbal. She has the habit of kneading her brother’s ear. Mam says that this is because Leonie did not breastfeed Kayla. Mam says the kneading of her brother’s ear is her substitute for the comfort she was not given by her mother. Mam is a compassionate woman and a healer, not just for those in her family but also for others in the community. She would have helped raise Jojo and Kayla since their father is in prison and their mother is rarely there either physically or emotionally, but Mam is on her deathbed, on her last lap with cancer. So Jojo functions as Kayla’s parent. He takes care of her needs. If Leonie comes near her, she cries and puts her head on Jojo’s chest.

Leonie admits her shortcomings: “And I stand there, watching my children comfort each other. My hands itch, wanting to do something. I could reach out and touch them both, but I don’t.” Her life is not about being a caretaker. She doesn’t have the psychic space for it. When her older brother Given was still in high school he was murdered. His death preoccupies her. Leonie comes from a loving household, but that’s not sufficient. She can’t shake what happened to her brother. She is in trauma.

She deals with that trauma by falling in love. But it’s who she fell in love with that causes her to be haunted by Given’s ghost. Given appears to her because it was a cousin of Michael’s who murdered him. The murder was called a hunting accident by Michael’s family. Though the murder was intentional—an outsized act of jealousy about a lost bet—the cousin served only a mild sentence at Parchman. But this does not keep Leonie from falling into Michael’s embrace:

From the first moment I saw him walking across the grass to where I sat in the shadow of the school sign, he saw me. Saw past skin the color of unmilked coffee, eyes black, lips the color of plums, and saw me. Saw the walking wound I was, and came to be my balm.

Jojo, who has stopped calling Leonie by any maternal name, has got her number: “She ain’t Mam. She ain’t Pop. She ain’t never healed nothing or grown nothing in her life…. Leonie kill things.” Jojo notices this because he sees. He is not just observant—he is a seer. His ability to see and the development of his seeing in the course of the novel are what gave me the confidence that this young man will break the cycle of incarceration that has snatched two generations of men in his family.

Jojo understands he has to face death to become a man like Pop, his grandfather, whose name is River. He wants to stand straight and tall like Pop. He does not blink as his grandfather kills a goat. But when the goat’s guts are being pulled out, “the smell of death” conquers him: “The rot coming from something just alive, something hot with blood and life.” He runs away and vomits.

Advertisement

Sing, Unburied, Sing has an abundance of smells—vomit, liver frying, pasta sauce, body odor, salt, sulphur, pine, lemon cleaner, fried potatoes. They waft through the humid Mississippi spring weather. Jojo often describes odors. He smells as if he’s sniffing for the death he knows he must face. Jojo is on a mission. Manhood is essential. He is very clear about what he needs to do to get the firm foundation that his parents cannot provide. It’s all about the knowledge that Pop is carrying from the past to the present:

He tells me stories…. Sometimes he’ll tell me the same story three, even four times. Hearing him…makes me feel like his voice is a hand he’s reached out to me, like he’s rubbing my back and I can duck whatever makes me feel like I’ll never be able to stand as tall as Pop, never be as sure.

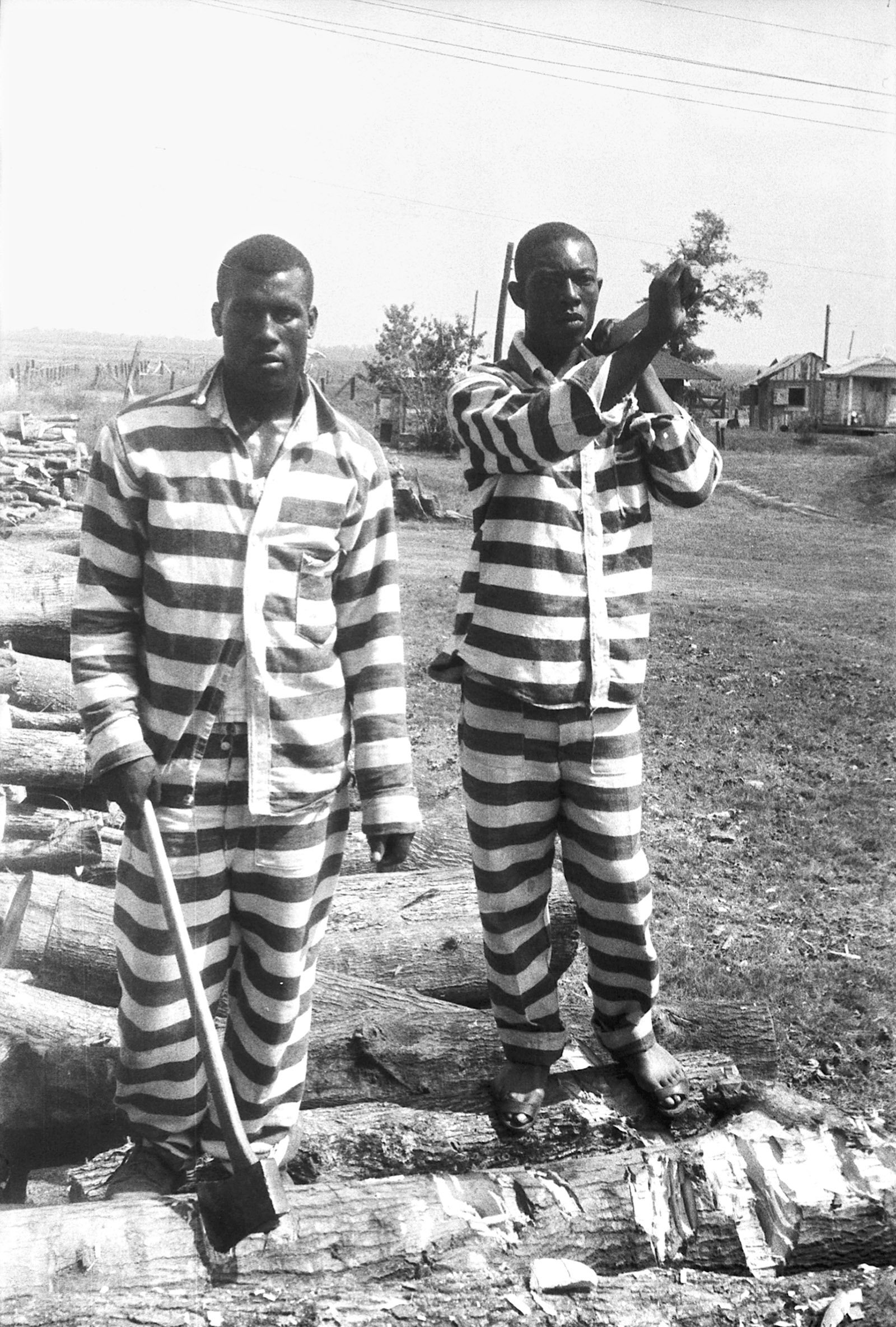

Alan Lomax Collection/American Folklife Center, Library of Congress/Association for Cultural Equity

Inmates at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman when it was a work farm, 1959; photograph by Alan Lomax from Parchman Farm: Photographs and Field Recordings: 1947–1959, published by Dust-to-Digital

There’s one particular death-filled story that Jojo is after. Mam warns him that Pop doesn’t tell the full story and sometimes mixes it up. River was taken to Parchman when he was fifteen. His brother, Stag, killed a white man in a juke joint. (Stag is perhaps inspired by the criminal in the folk song “Stagger Lee,” of which Lomax recorded a version called “Stackalee” at Parchman in 1947.) Stag went to Parchman prison for murder, and River—who just happened to be in the vicinity of his brother—went too for “harboring a fugitive.” At Parchman he saw and experienced the unimaginable. The third narrator of this story is the ghost of a boy named Richie who was twelve years old when he went to Parchman. He tells Jojo that the inmates nicknamed Pop River Red because “he rolled with everything like a river, over the fell trees and stumps, through storms and sun.” Then one storm broke that he could not roll through. Jojo wants to know what stopped River from rolling.

There are two Parchman prisons for Jojo. There is the modern prison where his father, Michael, is incarcerated. Doing time there now is very different from doing time the way his grandfather River did time. In his book, R. Kim Rushing interviews a current inmate identified as Terry Wilkins:

I’m in this 10×10 room 24 hours a day and seven days a week. This is where time starts doing you. Just set back and think of your self setting in a room the size of a small bathroom. Day and night. Month after month. That’s doing time.

Pop/River was at Parchman when it was a work farm—a profitable cotton plantation. River did not live in a ten-by-ten room. Inmates worked and lived in a wide open space, but open space, he says, does not mean freedom:

You see them open fields we worked in, the way you could look right through that barbed wire, the way you could grab it and get a toehold here, a bloody handhold there, the way they cut them trees flat so that land is empty and open to the ends of the earth, and you think, I can get out of here if I set my mind to it. I can follow the right stars south and all the way on home. But the reason you think that is because you don’t see the trusty shooters. You don’t know the sergeant. You don’t know the sergeant come from a long line of men bred to treat you like a plowing horse, like a hunting dog—and bred to think he can make you like it.

Parchman prison, established in 1901, was a barbaric extension of slavery. Its contribution to prison reform in the earlier part of the twentieth century was its introduction of conjugal visits on Sundays. At first, only black prisoners of Parchman were allowed conjugal visits. It was a while before the white prisoners could partake of the advantage. “You gotta understand,” a sergeant at Parchman says in Oshinsky’s book, “that back in them days niggers were pretty simple creatures. Give ’em some pork, some greens, some cornbread, and some poontang every now and then and they would work for you.”

When Michael gets released from prison, Leonie makes Jojo and Kayla accompany her to pick him up. It is on this road trip with his mother and her drug buddy, Misty, that Jojo comes into contact with the death he wants to know. On their way back from Parchman, Michael in tow, they are pulled over by the police. In the course of the near arrest, the officer handcuffs Jojo, throws him to the ground, kicks him, and puts a gun in his face. His little sister is near the gun too.

This harrowing scene would itself be a rite of passage for many thirteen-year-old American black boys. But something else demands Jojo’s attention—the ghost of Richie. Richie came under Pop’s protection when he went to Parchman and he died there under circumstances that keep him from finding peace in death. The ghost of Richie is what Jojo needs to get the full story of his grandfather’s years in prison. Having come back with Richie’s ghost at his side, and with Richie’s wordless songs in his ear, he gets Pop to fill in the blanks of the story. Once the story is complete, Mam crosses into death, and Jojo starts to see the tree of ghosts he knows he must see in order to be a man.

The literary accomplishment of Sing, Unburied, Sing has been widely appreciated: it received glowing reviews and won the National Book Award for fiction. Having traveled the modern school-to-prison pipeline around the US, I find this book important for another reason. In research institutes and departments of education, children like Jojo and their families are data. The data are essential, and it is crucial that the magnitude of the problem of mass incarceration be made visible. But data only tell part of the story. Sometimes those who collect data, for the sake of making a case, identify humans by the marks of their circumstances. As the extreme-action choreographer Elizabeth Streb told me in an interview:

Like how much, how many feet of protection does who get, on earth? How high are their fences? Like the people who are the richest are the furthest away from any type of penetration. The poorest people, you know, have scars on their face? Because they, they can’t keep harm away from them.

Ward’s characters are much more than their scars. The novel suggests that you have resources to get you through, regardless of your circumstances. Some of those resources are not tallied by experts. The ear might be a better way of finding those resources than looking at numbers on a spreadsheet. And it takes a certain kind of ear.

When I listened to the 1940s recordings of Alan Lomax interviewing the musicians at Parchman prison, I heard his questions far in the background. His tone of voice seemed to invite the speaker to speak. That’s how I read Ward’s relationship to the voices of her characters. She accepts—perhaps welcomes—her characters, with all their flaws. Her attitude toward them reminded me of people I met in the trenches and on the front lines of the school-to-prison pipeline. I call them the “walkers.” I met them in schools, in prisons, in county jails, in a public defender’s office, by a river with a salmon-fishing tribe. The walkers go the distance with those they serve no matter how egregious their actions and no matter how many times they fatten recidivism rates.

During my travels, I was at first surprised to hear the word “trauma” used by so many different kinds of experts. I heard it from activists, members of the judiciary, and scientists, to name a few. I came to appreciate their awareness that both present trauma and historical trauma have a negative impact. And yet, there was something missing: that certain kind of listening that one experiences when listening to music. Among the many recordings Lomax made at Parchman was one of a conversation he had with W.D. Stewart (“Bama”) in late 1947:

Lomax: Do you think it makes work easier when you sing?

Bama: Yessuh…. What makes it go so better when you singin…. You might not forget you see, and the time that’s pass on. But if you get your mind devoted on one something…it look it be hard for ya to make it see, to make a day, a day be long it look like. Keep your mind for bein devoted on just one thing why you just practically take up singin see.

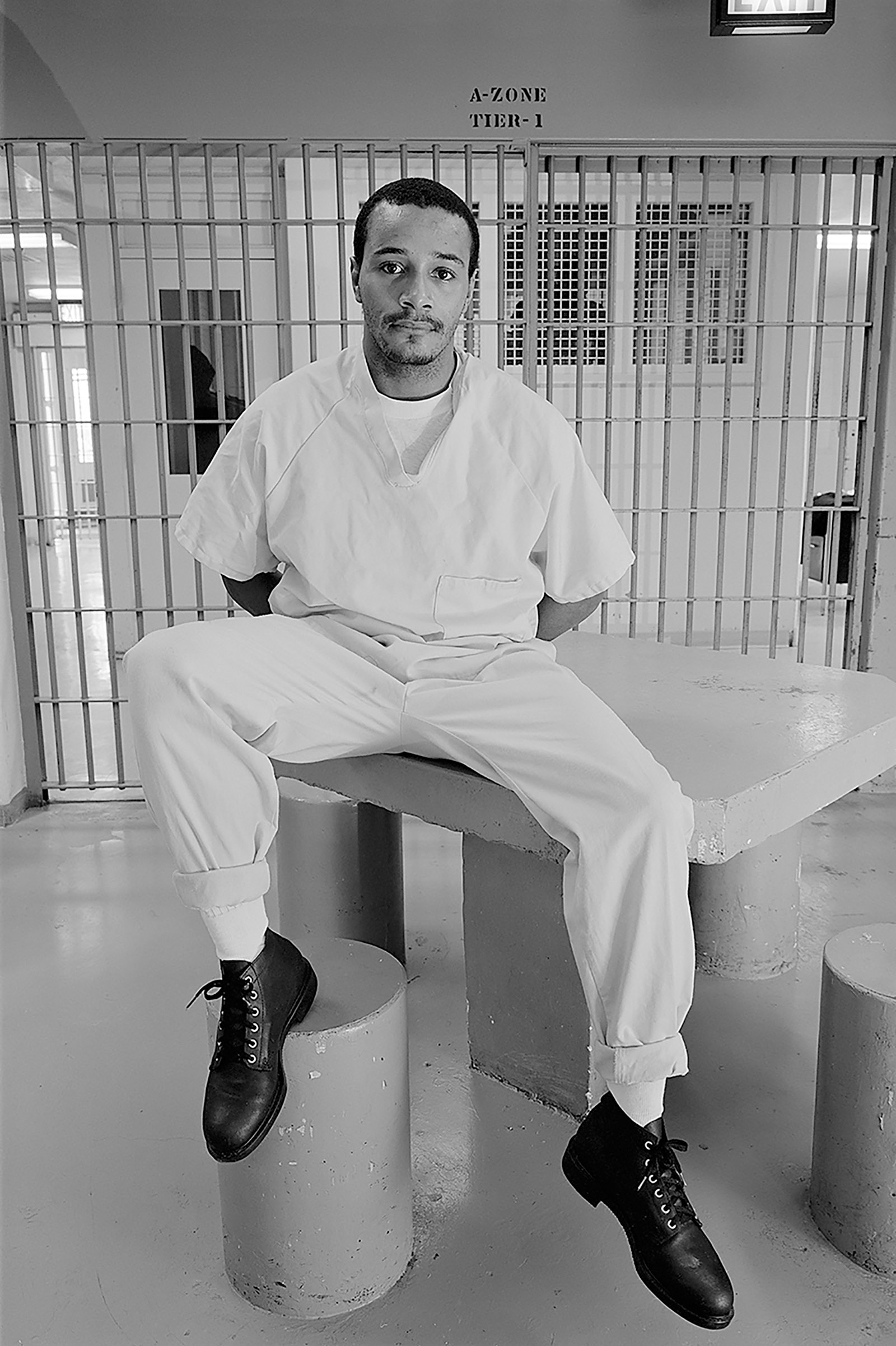

Sing, Unburied, Sing honors paying attention: seeing, listening, and, finally, singing. The novel inspires me to think that we need new songs, new ways of seeing, new ways of listening. Prisons are highly mechanized technological places with little space to move—very circumscribed spaces in which to sing. I visited Lee Correctional Institution, a maximum-security facility in South Carolina. While there, I was invited to a concert at which inmates performed with Decoda, an ensemble of young classical musicians, some trained at Juilliard, who play at venues from Carnegie Hall to prisons.

Jesmyn Ward has said in interviews that Parchman, about three hundred miles north of her Mississippi hometown, had interested her for a long time before she wrote Sing, Unburied, Sing. The same is true of Claire Bryant, one of the founders of Decoda, who lived near Lee Correctional in South Carolina as a girl. Claire went to Lee to conduct a music workshop with the inmates in which they were encouraged to compose and prepare for a performance. She had little time. She therefore quickly identified the natural musicians and trained them to teach other inmates. Whatever skill the inmates were able to refine in the controlled environment of prison was backed up by this group of proficient classical musicians. The resulting concert—a mix of genres—was breathtakingly beautiful.

The men and women in prisons across this country have an American song to sing, a story to tell. Even as there is an increased concern that our society has become too punitive, few of us know what that song might sound like. Arts programs in prisons—rare enough to begin with—are often temporary and vulnerable to cancellation. (The same is true of schools.) Apparently the overseers of Parchman prison in the early twentieth century saw the value of music. Work songs and field hollers were at the very least tolerated, because they moved the work along at a pace, and toward a profit.

Over the course of Ward’s novel, Jojo learns how to hear and see by embracing, body against body, his grandfather’s storytelling and his trauma. By the end, Jojo can see the entire tree of ghosts. The ghosts talk to him in a chorus of first-person testimonies. These testimonies are the story of historical trauma: “He raped me and suffocated me until I died…they came in my cell in the middle of the night and they hung me they found I could read and they dragged me out to the barn and gouged my eyes…he put me under the water and I couldn’t breathe.”

Jojo can also hear the significance of the song of his younger sister, Kayla, even though she is a toddler and can’t yet speak a full sentence:

Kayla begins to sing, a song of mismatched, half-garbled words, nothing that I can understand. Only the melody which is low but as loud as the swish and sway of the trees, that cuts their whispering but twines with it at the same time. And the ghosts open their mouths wider and their faces fold at the edges so they look like they’re crying, but they can’t. And Kayla sings louder. She waves her hand in the air as she sings, and I know it, know the movement, know it’s how Leonie rubbed my back, rubbed Kayla’s back, when we were frightened of the world. Kayla sings, and the multitude of ghosts lean forward, nodding. They smile with something like relief, something like remembrance, something like ease…. Home, they say. Home.

Once Jojo has embraced his grandfather’s pain, once he has seen and heard the tree of ghosts and listened to his little sister’s half-sung song, he can do the manly things he must do with a new energy. He has always known that his mother could not care for him, that she is trapped in the embrace of his father, a white man whose family excused the murder of Jojo’s uncle by one of their own. At the end of the novel, Leonie and Michael have left for a couple of days—presumably to get high. Jojo puts Kayla on the Head Start bus and comes back inside to get ready for school. One feels his dignity and is hopeful that he is going to be all right.

This Issue

March 8, 2018

Hell of a Fiesta

Roth Agonistes

-

1

David M. Oshinsky, “Worse Than Slavery”: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (Free Press, 1996). ↩

-

2

R. Kim Rushing, Parchman, with a foreword by Mark Goodman (University Press of Mississippi, 2016). ↩

-

3

Alan Lomax, Parchman Farm: Photographs and Field Recordings: 1947–1959 (Dust-to-Digital, 2014). ↩