1.

Founded in 1993 and operating out of two townhouses on New York’s Upper West Side, Bard Graduate Center has produced an admirable series of exhibitions and scholarly catalogs on subjects in its fields of study: decorative arts, design history, and material culture. Its monographic shows have focused on such figures as William Kent, the architect and pioneer of the English landscape garden; Thomas Hope, the collector of antiquities and definer of Regency design; and Charles Percier, Hope’s equivalent in France, inventor of the Empire style and codesigner of the rue de Rivoli. The catalogs of such exhibitions form an impressive, coherent group—an accumulation of expertise.

Among the surprises sprung by the center was a charming small display in 2013–2014 recording a period in which, while the French textile industry ground to a halt during World War I, an attempt was made in New York to create a new American decorative art not beholden to Europe, using the design language of pre-Columbian America and other “primitive” cultures. To this end, the American Museum of Natural History encouraged fashion designers to study and copy textiles and garments from its extensive holdings, and amateur models were photographed wearing original items from the collections: a Sioux dress with a beaded yoke; a Tungus Siberian reindeer fur and sinew coat; an Ainu bark fiber robe.1 Doubtless no great harm was done to the textiles in question. One presumes, however, that today such a use of a museum’s materials—using the museum like a dressing-up closet—would be absolutely taboo.

And not only taboo. The promotion of industrial art and design must rank low on the list of ways a modern anthropological museum wishes to engage with the world. Not so in 1919. Then the AMNH and the Brooklyn Museum joined forces for an exhibition of industrial art that showed what modern looms could produce when inspired by primitive looms and preindustrial design: the taupe silk charmeuse teagown with Bukharan motifs and the Sunset Fan-Ta-Si silk dress with blue duvetyn appliqué based on a Nanai fish-skin coat were among the proposals of the wartime ethnic look. “LADY or SQUAW,” declared an advertisement in Women’s Wear, “She Obeys the Impulse to DRESS UP.”

This concern of cultural institutions to direct and enrich the course of modern manufacture may be traced back to London, to the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the founding of what later became the Victoria and Albert Museum. Many imitations of the V&A sprang up around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which once used to look much more like a museum of manufacture, a look it progressively shed during the last century.

When J. Pierpont Morgan and his son purchased the Hoentschel Collection and donated it to the Met, starting in 1906, one of their major purposes was to make available to the public fine and authentic examples of French decorative art from its greatest period. Georges Hoentschel had run a highly superior business in architectural salvage in Paris, and his collection was a compendium of the best paneling, furniture, frames, and metalwork from the period of Louis XIV to Louis XVI. The idea was that if you wanted to know how the doors in your apartment should look—what kinds of hinges and locks, what kinds of keyhole escutcheons—you could go to the Met, or send your man there, find what you needed, and have it copied. And thus taste would be elevated throughout the city, throughout the country.

To an extent, it worked. Here is Elsie de Wolfe, the pioneering interior decorator, in The House in Good Taste (1913):

The workers of today have their eyes opened. They have no excuse for producing unworthy things, when the greatest private collections are loaned or given outright to the museums. The new wing of the Metropolitan Museum in New York houses several fine old collections of furniture, the Hoentschel collection…having been given to the people of New York by Mr. Pierpont Morgan.

In due course, as modernism increasingly prevailed in the world of interior design, this aspect of the Met’s mission was forgotten, and the Hoentschel collection went into storage. There followed what have been called the Wrightsman years, in which the emphasis of the Met’s displays shifted to flawlessly realized and furnished interiors—complete rooms. Never has the ancien régime looked better, and cleaner, than it does in the crepuscular gloom of the Wrightsman Galleries, whose great strength is in the conveying of an Authentic General Effect. One is of course at liberty to peer at the details of carving, gilding, weaving, and chasing. But that is not the main point.

Advertisement

In 2013 the Bard Graduate Center was able to borrow items from the Hoentschel Collection in order to mount a revealing exhibition (with the usual outstanding catalog) about Hoentschel as a designer and collector and, it turned out, highly original ceramicist.2 What one saw was a different kind of authenticity—analytic, fragmentary, a past glimpsed through orphaned objects and unrestored surfaces. God, or the Devil, is in such details, and the details—the faucets and finials, the chair legs and newel posts—are now back in storage.

The center’s most recent show reprised the theme of the museum in relation to industry and craft. This time the subject was India, and the monographic focus was on John Lockwood Kipling, the father of the poet Rudyard. He was an artist and illustrator, a sculptor, a designer, a teacher, a museum curator, and, like his son, a journalist. The catalog is the result of an editorial collaboration between Julius Bryant of the V&A and Susan Weber, the founder and director of the Bard Center. Taken together, the various essays make an unanswerable case for the interest in Kipling’s father, a figure we might never have thought about before, unless we knew him as the original illustrator of The Jungle Book or of Kim, or unless, reading Rudyard Kipling’s unbearably sad autobiographical short story “Baa Baa, Black Sheep,” we had wondered about the parents who abandon their infant boy and girl, brought up in Bombay, to a foster home in England—weeping and choking as they do. One might think that the accusation leveled by the son (you put us through this torture) might be too much for a father to bear.

It turns out, though, that Lockwood and Rudyard in later life became the best of friends and collaborators. The father must in some way have accepted the justice of the rebuke contained in the story’s last paragraph: “For when young lips have drunk deep of the bitter waters of Hate, Suspicion, and Despair, all the Love in the world will not wholly take away that knowledge; though it may turn darkened eyes for a while to the light, and teach Faith where no Faith was.”

Father and son, however, not only hit it off. They worked together, discussing Kim, for instance, as it was being written. And indeed the first chapter of Kim features a portrait of Lockwood Kipling, in the form of the white-bearded curator of the Lahore Museum—the “Wonder House,” as the book has it—who receives the Tibetan lama in his office and shows him photographs of the very lamasery he has come from.

Everything in that opening chapter is extraordinarily specific. Rudyard makes it clear that the pilgrimage on which the lama and Kim embark has its beginning in (though he does not use the term) the Gandharan sculpture section of the Lahore Museum among “the larger figures of the Greco-Buddhist sculptures done, savants know how long since, by forgotten workmen whose hands were feeling, and not unskillfully, for the mysteriously transmitted Grecian touch.” There is much detail about Buddhist scripture as it is illustrated in Gandharan relief—so much, indeed, that Lockwood anticipated that Kim would prove difficult for the uninitiated reader. But he thought that was as it should be. There is a respect here for Indian art and philosophy that was far from common among the British at the time.

2.

The story of the British encounter with Indian art and architecture is full of surprises. For instance, it was discovered not so long ago that the playwright and architect (of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard) Sir John Vanbrugh spent a part of the 1680s (his “missing years”) in Surat, Gujarat, working for the East India Company, where he is said to have been influenced by the architecture of the local cemeteries.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, the historian, went to India in the 1830s to write the Indian Penal Code, but found time to begin the Lays of Ancient Rome (one of the most popular volumes of English poetry ever) in the hill station of Ootacamund. Macaulay looked at the old forts of India and was reminded of Oxford—some of the shabbier colleges, he says. He looked at the rural architecture around Madras and was reminded of the small town of Llanrwst in North Wales (a more difficult comparison to grasp). “There are some signs,” he adds, “that the people in these huts have more than the mere necessaries of life. The timber over the door is generally carved, and sometimes with a taste and skill that reminded me of the wood-work of some of our fine Gothic Chapels and Cathedrals.”

About the villas of Europeans in India, Macaulay makes a pregnant observation:

Advertisement

They are large and sometimes very shewy. But you may see at a glance that they are the residences of people who do not mean to leave them to their children or even to end their own days in them. There is a want of repair—a slovenliness…which marks that the rulers of India are pilgrims and sojourners in the land. You will see a fine portico spoiled by a crack in the plaister which a few rupees would set to rights—gaps in hedges—breaches in the walls—door off the hinges, and so on. As no Englishman means to die in India…nobody pays the attention to his dwelling which he would pay to a family house. It is curious that the neatest and most carefully kept houses which I have observed are those of half-casts and Armenians, who mean to end their days here.

If it was true that no Englishman—as an individual—meant to die in India (Macaulay himself got out the moment he had finished the Penal Code), the British as a nation were determined to hold on to the subcontinent at all costs—something they demonstrated not only by their thorough and bloody suppression of the Uprising or Revolt of 1857–1858 but also by the complete reorganization of the Indian government in its relation to the Crown.

The shock delivered by the Indian Mutiny (as the British dubbed it) can be sensed in the opening pages of the first lecture in John Ruskin’s The Two Paths, which he delivered at the V&A in 1858–1859, and which Lockwood Kipling would have either heard at the time or read shortly afterward. Ruskin asks his audience how it comes about that a land devoid of visual arts, such as the Scottish Highlands, can produce people of exemplary virtue, while a country notable for its love of subtle ornament and design, India, goes in the opposite direction. He is thinking of the gratitude the British owe to the Scottish regiments in their

victories in the Crimea, and your avenging in the Indies…. Out of the peat cottage come faith, courage, self-sacrifice, purity, and piety, and whatever else is fruitful in the work of Heaven; out of the ivory palace come treachery, cruelty, cowardice, idolatry, bestiality—whatever else is fruitful in the work of Hell.

The degradation of the Indian mutineers has no precedent: “Since the race of man began its course of sin on this earth, nothing has ever been done by it so significative of all bestial and lower than bestial degradation, as the acts of the Indian race in the year that has just passed by.”

Ruskin asked himself how to explain the mismatch between this love of art and this Indian bestiality:

It is quite true that the art of India is delicate and refined. But it has one curious character distinguishing it from all other art of equal merit in design—it never represents a natural fact. It either forms its compositions out of meaningless fragments of colour and flowings of line; or if it represents any living creature, it represents that creature under distorted and monstrous form. To all facts and forms of nature it wilfully and resolutely opposes itself; it will not draw a man, but an eight-armed monster; it will not draw a flower, but only a spiral or a zigzag.

And so the Indians are cut off from all healthy knowledge and natural delight.

Aside from the notable ignorance of Ruskin’s remarks, there is a strain of madness or hysteria here. The decorative arts of India had long been known and valued in the West. It seems that Indian fine arts, by contrast, were slow to receive appreciation. Gandharan sculpture, in the Greco-Buddhist tradition, was one thing. But the art of the Hindu tradition—the great sandstone temple reliefs, architectural elements, and the statues of the gods—probably more than anything else inspired a kind of horror in those who cared to look at them. They were idolatrous. They were also often obscene. Sir George Birdwood, the “Art Referee for the Indian Section of the South Kensington Museum” (renamed the Victoria and Albert in 1899), wrote as late as 1880 that “the monstrous shapes of the Puranic [that is, Hindu] deities are unsuitable for the higher forms of artistic representation; and this is possibly why sculpture and painting are unknown, as fine arts, in India.”

3.

Lockwood Kipling, born in 1837 into a Methodist family in the North of England, was inspired by a visit to the Great Exhibition of 1851 to become an artist and a craftsman. He served an apprenticeship with a ceramics manufacturer, Pinder, Bourne and Hope—not exactly a household name, and not, one might have thought, in smoke-blackened Stoke-on-Trent, a promising start to an artistic career. Intriguingly, though, Kipling was taught at the Potteries School of Art by, among others, the French sculptor Albert Carrier-Belleuse, who specialized in architectural sculpture (at the Paris Opera and the Louvre, for instance) and who later employed Rodin as his assistant. Carrier-Belleuse was at that time in England working for Mintons. Later he became head of the Sèvres manufactury and took Rodin with him. So Lockwood Kipling’s start in life was not so odd for an aspiring artist.

Architectural sculpture, ceramic and stone reliefs, and all kinds of ornamental work were required on the grand public buildings that were going up in Britain and in the British Empire: Gothic buildings, French and Italian renaissance buildings, buildings of a strange, exuberant eclecticism, with Venetian façades and metal structures resembling tram sheds or railway stations. One such was the South Kensington Museum itself. As recently as 1982, when John Physick wrote his history of the museum’s building, no one could explain why Lockwood’s portrait, in mosaic, is included on the original front entrance in a procession of dignitaries. The answer is that Kipling had helped Godfrey Sykes model most of the terra-cotta decoration of the exterior, but that somehow it had slipped from the record.

Kipling and his wife, Alice, were both of Methodist stock, and both came to reject the religion of their upbringing—Alice with a memorable gesture. She was a teenager when, family legend had it, she came upon a lock of John Wesley’s hair—a pious souvenir of the great preacher. This she “triumphantly” threw in the fire, with the gaily offensive words: “See! a hair of the dog that bit us.” She was “artistic” (a term then used for women who dressed somewhat unconventionally) and related by marriage to Edward Burne-Jones and to another painter less well known today but in his time highly successful, Edward Poynter. She wrote, but only pseudonymously. She seems to have been ambitious, like her husband, and going to India, as a young pregnant wife, was perhaps a sign of that ambition. But in Bombay and Lahore she was definitely restricted in what she might actually do. She was witty and on occasion referred to as sour. Those who liked the Kiplings seem to have liked them a great deal. Others found something unpleasant in their company—something no doubt to do with the frustrations of class.

In India, when the Kiplings arrived in 1865, the buildings that had once struck Macaulay as being so ill-kept had been mostly Palladian in design. But after the Revolt of 1857 the new style for the public buildings in Bombay was Gothic, and the Bard catalog tells us that “still, today, Mumbai can boast the world’s finest assembly of Victorian Gothic architecture, much of it encrusted with sculpture modeled and carved by Kipling and his pupils.”

Lockwood and Alice had come to take advantage of the boom city. Bombay in the 1860s profited from the blockade of the American South and was growing rich through the export of Indian cotton to the Lancashire mills, as well as Indian opium to China. The couple began their Bombay residence in tents on the Esplanade, and Lockwood taught sculpture in a temporary shed nearby, while the place of his employment, the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art and Industry, was being designed (back in England) by the notable medieval-minded architect William Burges.

Kipling was critical of what had passed for architecture in British India:

The architecture imported by the English has…done more grievous injury than can be estimated with calmness. Barracks, churches, and houses, designed for the most part by people who have had no education in architecture of any kind, but who are at best fair engineers, are looked on by natives as authoritative examples, and their blank ugliness is copied with exasperating fidelity…. There are many who think that when they have reared a clock tower in nineteenth-century British Gothic in the centre of a native city they have taken a serious step in the march of civilisation.

This might be read as a barb aimed at many a Bombay project, including several to which Lockwood had himself contributed (such as the market fountain in Bombay closely modeled on one designed by Burges for the city of Gloucester). By contrast, when in due course Lockwood moved on to Lahore to head an art school and museum there, he sought to pioneer a style based on local traditions. One of his chief concerns was the preservation or revival of Indian artistic practices. “It is on the architecture of today,” he argued, “that the preservation of Indian art in any semblance of healthy life now hinges.” To this end he not only collected Indian arts and crafts. He also drew charming studies of craftsmen at work. One feature of the Lahore museum that caused great interest among visitors was a series of small models of such craftsmen, accurate in all details of their trade. Lockwood was concerned to find markets for Indian work, and made sure that it was represented in the kind of international fair that had sprung up after the model of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

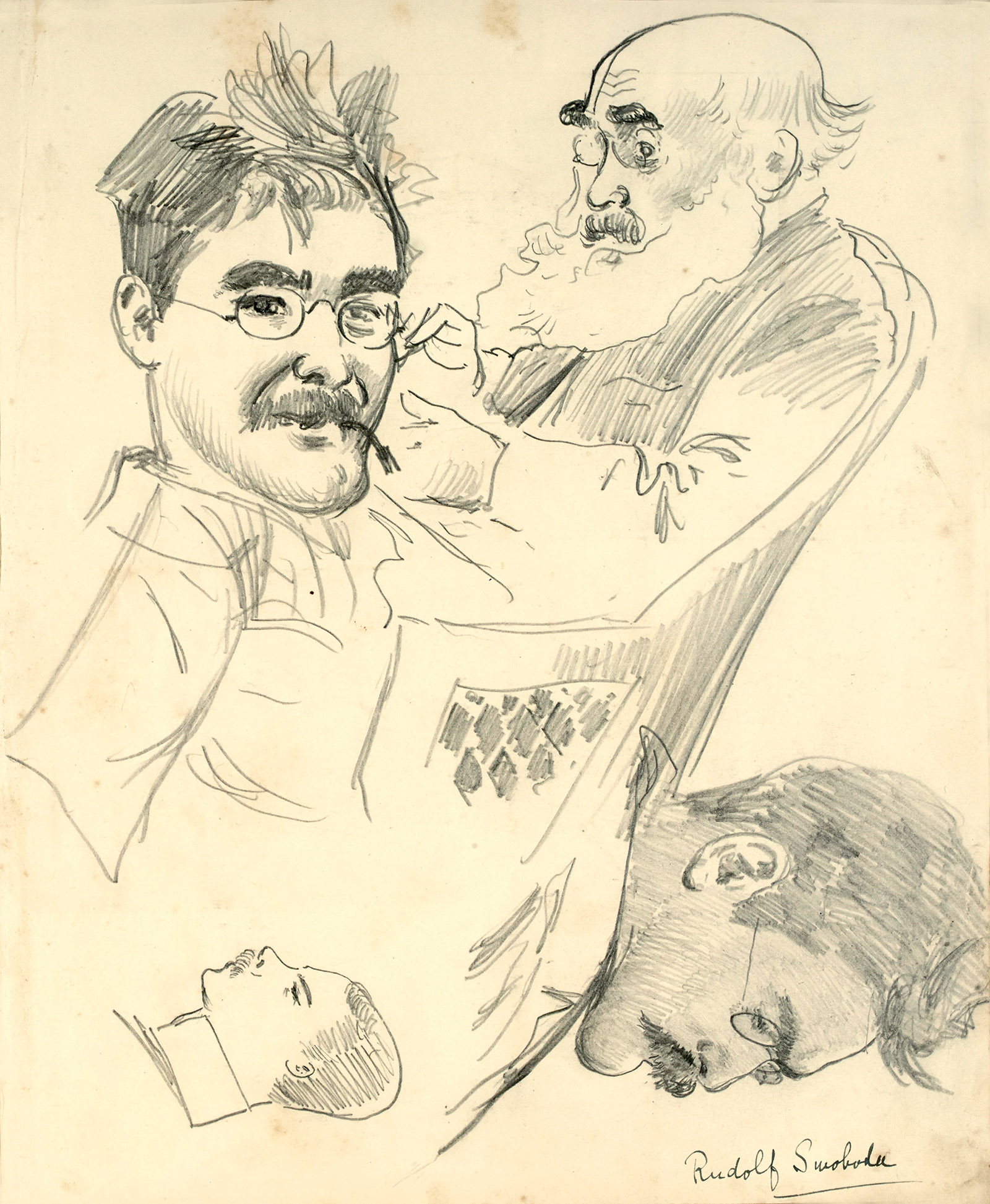

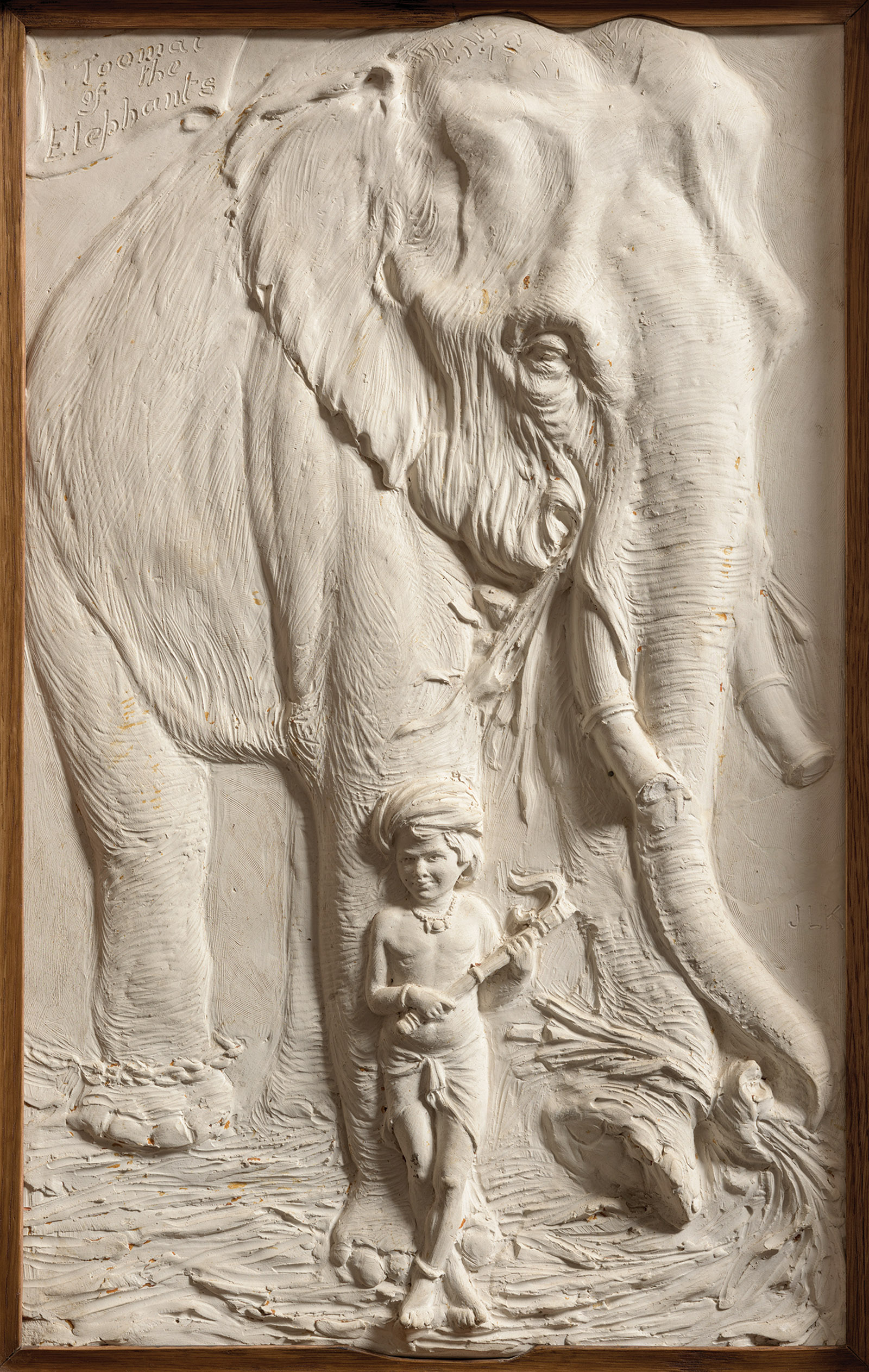

Had he not devoted so much time to this educational and administrative work, he could easily have made a living as a sculptor. He had a particular gift for working in relief (the catalog suggests that was influenced by the Donatellos at the V&A), and sought new ways of using it. So the illustrations to Kim were modeled in plaster relief and then photographed—an original combination of media.

It is astonishing to me how much has been retrieved by the scholars involved in this enterprise. As the Raj recedes it loses perhaps just a little of its toxicity. It has become possible to take a closer look at Rudyard Kipling, and that closer look often includes Lockwood Kipling in the frame. Then the father becomes interesting for his own sake—something the son would never, it seems, have resented. One cannot help wondering how many comparable figures are waiting for such an unexpected revival.

-

1

Ann Marguerite Tartsinis, An American Style: Global Sources for New York Textile and Fashion Design, 1915–1928 (Yale University Press, 2013). ↩

-

2

Salvaging the Past: Georges Hoentschel and the French Decorative Arts from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, edited by Daniëlle O. Kisluk-Grosheide, Deborah L. Krohn, and Ulrich Leben (Yale University Press, 2013). ↩