The story of the Jews extends farther back into the past than that of any other faith: perhaps only Hindus and Zoroastrians come close. But having more history does not help in the writing of it. On the contrary: the difficulties have been evident since the appearance of the first standard history of the subject, Heinrich Graetz’s compendious Geschichte der Juden, in the middle of the nineteenth century. What does it mean to write the history of a religious group? Is one charting the vicissitudes of a creed? Or is the real story the fate of a people?

There is the risk of seeking—and hence finding—some essential core of Jewishness that may, in fact, never have existed. Alternatively, since Jews have existed as a minority in most times and climes, living among others with other beliefs, the subject may dissolve before one’s eyes. Is there really a Jewish history independent of the histories of these larger societies? Take architecture, clothes, food: in their way of life don’t the Jews of Cochin, for example, have more in common with the sultans of Mysore than they do with the Vilna Gaon?

The pioneering Graetz, an early participant in the struggle between reform and conservative Judaism, was a scholar who believed in Wissenschaft—scientific study. But he was also not afraid to embellish the evidence when required, and some accused him of playing fast and loose with the facts. Indeed, one of the charges laid against him was that he gave his readers stories (Geschichten) rather than history (Geschichte).

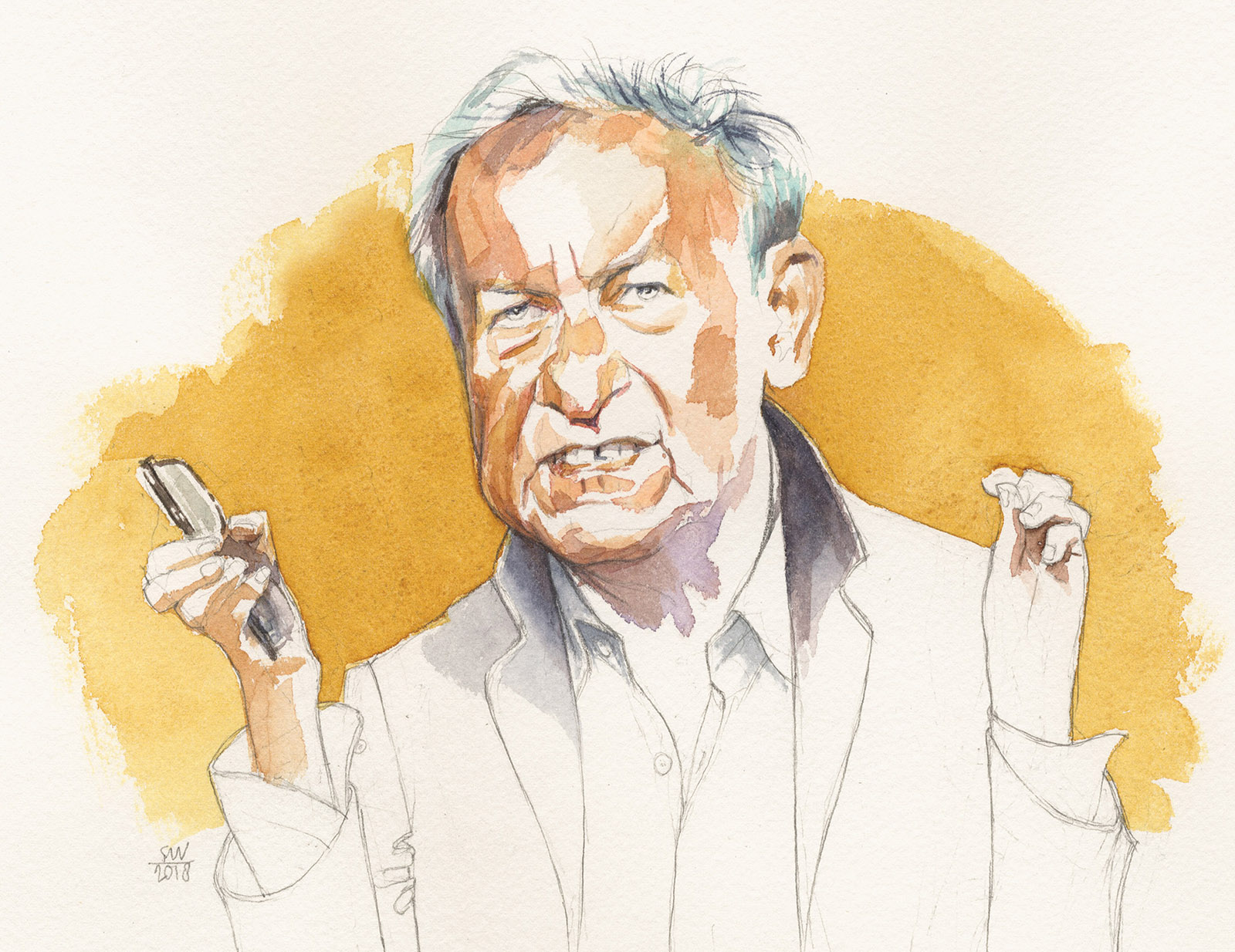

This brings us straight to Simon Schama, who has been interested in the relationship between the storyteller and the historian for about as long as he has been interested in the Jewish past. One of his very first books treated the impact of the Rothschilds’ philanthropy in the Holy Land. His tale-filled, genre-defying Landscape and Memory (1995) opened with his Ashkenazi forebears in the forests of tsarist Russia. The Story of the Jews, his television series first broadcast in 2013, marked his most sustained engagement with the subject. Now comes the tie-in, a multivolume history likewise entitled The Story of the Jews. The first volume, Finding the Words (2013), took the story from biblical times to 1492; Belonging is the second. A third is promised.

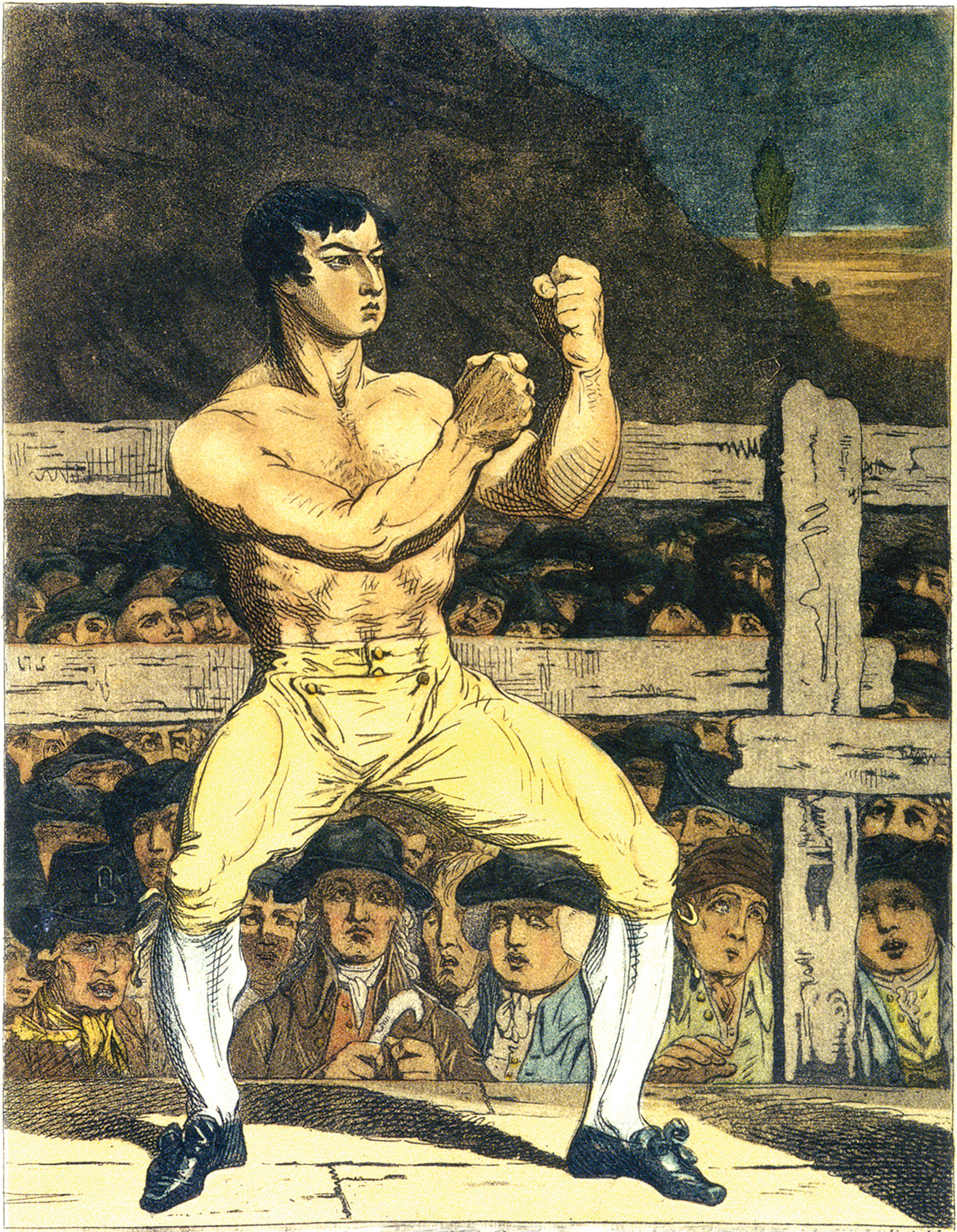

The story? More like a bevy of them—the wilder the better. Schama begins among the swirling millenarian expectations and false messiahs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and concludes with a loving account of Theodor Herzl and his dream of building Zion in Ottoman Palestine. In between is a roller coaster of a ride that takes us from the New Christians and the conversos of Iberia to Jewish power centers in ports like Antwerp and Izmir. Glamorous figures such as Beatriz de Luna and her nephew Joseph Nasi, the Duke of Naxos, head a colorful and varied cast. There are pen portraits galore—the first Jewish playwright, the passions of an early poetess, and the pugilistic feats of the famous eighteenth-century boxer Daniel Mendoza. The geographic reach is vast—from the communities of China and India to the American colonies.

In a career spanning forty-plus years Schama has become more than a historian. A prolific and acclaimed broadcaster, straddling history and the visual arts, he is renowned for the brilliance of his style and the extraordinary range of his learning. If Graetz wrote to educate rabbis, Schama’s books, Op-Eds, and TV shows have been designed for a very different purpose: to bring the past to life with all the excitement and imaginative power at his disposal in order to reach as wide a public as he can.

Back in 1991, he wrote an essay for The New York Times entitled “Clio Has a Problem,” in which he warned that professional historians were hobbling themselves with political correctness and analytical aridity, losing sight of the bigger picture by setting expertise above plotlines and drama. They were—horror of horrors—making the past dull. What he wanted was “literary playfulness.” He demanded “great narratives” written in “thrilling, beautiful prose” and capable of stirring or seizing the imagination. By this point, two of his books already showed what he had in mind: The Embarrassment of Riches (1987), about the Golden Age Netherlands, and his study of the French Revolution, Citizens (1989). More followed, including Landscape and Memory and a three-volume history of Britain. Now it is the Jews’ turn.

Schama’s mentor at Cambridge was J.H. Plumb, an influential don and argumentative popularizer who detested the drab pretensions of “scientific history.” Plumb’s own supervisor had been the master storyteller of twentieth-century British Liberalism, George Macaulay Trevelyan. In scholarship, lineage counts, and in that 1991 essay Schama seemed to be arguing that history should return to the example set by his Cambridge forefathers: it needed to leave specialization behind and return to narrative. Yet recently his discomfort has seemed to reflect less a critique of history’s overprofessionalization and more an impatience with the discipline itself. It is as if he has resolved to set the past free from the historians.

Advertisement

This is perhaps why his books increasingly rely on the vignette, the portrait, the set piece, and the mis-en-scène, while anything as mundane as argument, analysis, or even sustained engagement with other scholars is given short shrift. An episodic mode of presentation suited another recent book of his, The Face of Britain (2015), which presents the past through a sequence of glittering extemporizations, each one inspired by a particular visual image. But The Face of Britain does not purport to be a work of history. With The Story of the Jews: Belonging, 1492–1900, things are less clear-cut.

Schama’s trademark prose has always been a showman’s vehicle, the restless, stylized marker of his literary ambition. But his writing has been obliged to do more and more work over the years. Back in the day of Landscape and Memory, brilliance lay in his insights as much as in the words themselves; style and analysis held each other in balance. In Belonging, explanation has receded to the vanishing point. We are never told, for instance, why the post-Iberian story of the Jews in the Netherlands and the Ottoman Empire is so important as to warrant opening with it. We learn that a new form of historical consciousness emerged among Jews in the early modern Mediterranean but not why, or where it went. Thorny questions about the structure of communal power, questions that scholars have argued about for decades, are sidestepped. Much more attention is given to Jewish mysticism than to Jewish rationalism; more time is spent in the Low Countries and Italy than in Eastern Europe and Russia. None of these preferences is necessarily wrong in itself, but none is argued for or explained. Instead, the book depends on its stories and their telling.

To say that Schama’s prose compels attention is an understatement—on page after page the verbal fireworks fizz and crackle. The obvious diagnosis is that this betrays some chronic fear of being boring. But television too has left its mark. The small screen does not just encourage the big personality; it has a personality of its own. Disliking numbers, statistics, or the abstract, it prizes the episodic and the anecdotal and whatever can be packed into it. The modern camera lingers lovingly over the materiality of place, landscape, food, and dress, and these get doled out in abundance on the page here. Schama likes listing stuff—a cataloging of the commodities Ashkenazi merchants traded in runs to sixty-five items—and quickly gets gustatory. In Antwerp, he tells us:

Pasties and tarts, loaves and puddings, all were transformed by a hit of sugar and spice. The whimwham, the posset, the custard and the cake all wanted dusting—so much toothsome powder in a sprinkling of pulverised grains and pellets. East met West when cumin seeds or cloves studded a plain hard golden cheese and made it fragrant. A dish of beans would get a dusting of nutmeg (as it still does in Antwerp and Amsterdam, where any kind of green beans are known as sperziebonen); the torture of a throbbing tooth would ebb after a drop or two of oil of cloves.

In Ottoman Istanbul:

There was a time when Jewish catering opened doors. Every Friday afternoon, following Muslim prayers but before the Jewish Sabbath, a caravan of confections from the villa of the Great Jew in Pera was delivered to Topkapi Palace. Seated upon silk cushions, the yellow-haired sultan, Selim II, awaited with keen anticipation the delicacies brought to him on Chinese porcelain: pigeon dainties baked in rose water and sugar; goose livers chopped with Corinth raisins and the spices which were, after all, the Jew’s to command; also some items preserved in the kitchen of culinary nostalgia, from the ancient Turkic days of tents and flocks and racing ponies; the sour yogurts and yufka, the unleavened bread that was wrapped around a pilaf.

It is a bit like reading some celebrity chef of the past, and one is slightly disappointed not to find mouth-watering recipes accompanying the text in little boxes.

Yet behind the strident dazzle of the style and the salivating, almost tactile quality of Schama’s imagery, there is something close to an argument, one that is all the more potent for being unstated. Sugar is sugar, isn’t it? Some things change, and some don’t. Well, maybe. But a history of the appetites can easily make the past seem too much like the present. A lip-smacking world, one that tastes like our world so long as we get the right mix of the ingredients, is a world in which some of the essential differences of the past have vanished beneath the frosting. What it gives is not immediacy but the illusion of it, an illusion in which Schama’s heroes under their finery are the same as they have always been: Jews who are boisterous and resourceful, yakkers and machers, schlemiels and schnorrers, wearing their heart on their sleeve. We are, in short, in the world of the essential Jew.

Advertisement

In Belonging, this is a faux-Yiddish world that the author too often conveys through pizzazz rather than insight, flirting with schlock and relying on Jewish stereotypes that, as several other reviewers have already noted, crop up throughout. Beatriz de Luna is a model of “the modern Jewish matriarch”; Leone de Sommi is “the first unapologetically Jewish showman.” Look, the author tells us, like some fairground barker, here are Jews actually riding a bicycle—wow!—or going around without beards. Would one accept this from an author who was not himself Jewish, and who did not so doggedly assert his own identity? There is a fine line between being amusing and being in bad taste, and not all of Belonging’s readers will think that Schama stays on the right side of it.

Especially since on the page as much as on camera he plays up his role as the entertainer—half music-hall act, half prodigy. Histrionic asides signal to the reader that he is not your run-of-the-mill, dull historian: “The world was going to hell. Obviously, it was all the fault of the Jews.” There are the mock Yiddishisms—“Enough with the rubies already!”—and the tongue-in-cheek stage directions—“Enter the Jew. Enter Oppenheimer”—that turn history into melodrama. As for the generalizations, here’s an example: “Nothing about the Jews of eastern Europe…was ever static or parochial.” Nothing? One can forgive the odd exaggeration for effect, but was not the hide-bound, parochial life of the shtetl precisely what many late-nineteenth-century Russian Jews born into the Pale were doing their best to flee? The nostalgia of Fiddler on the Roof was one thing; the reality had been quite another.

And what has happened to the narrative, that larger story that Schama once argued so passionately for? Although it is sometimes hard to see whether there really is one amid the welter of anecdotes, it turns out that all these stories of his are contributing to a single message after all. It is less a story, perhaps, than a predicament, because the big story Belonging wants to tell is the old one of Jewish history as an eternal, almost Manichaean struggle between Jew and non-Jew. In grim counterpoint to Jewish energy, resilience, and chutzpah we have the drumbeat of “relentless persecution, massacre and oppression” that in Schama’s view constitutes the core of the Jews’ relationship with non-Jews over the centuries. Between them, he tells us, there can be no real trust; the best one can hope for is the coexistence born of “pragmatic need.” Not even in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was there anything close to “mutual sympathy.”

As his story progresses and the convivencia, or coexistence, of Iberia and the Ottoman realms is left behind, it becomes bleaker. By the nineteenth century’s end, “Jew-hatred burned through Europe.” The moral seems clear: Enlightenment is a chimera. Belonging is all. “Delusion and fanaticism act while all reason does is talk.” We are not even in the twentieth century but it is already clear that nothing good lies ahead.

Now one can easily enough recount the Jewish past as a saga of suffering—there has obviously been plenty of it. But to what end? Recollecting the past, after all, can serve more than one purpose. The holy books record the collective Jewish memory of the plagues in Egypt and the passage across the Red Sea into the Promised Land, the Temple’s destruction and the Babylonian exile. But for centuries, such stories succoured not historians but rabbis, and the injunction to remember was understood by them primarily as an ethical one.

It was Zakhor (1982), the historian Yosef Yerushalmi’s classic exploration of the connection between Jewish memory and Jewish history, that highlighted the relatively belated emergence of Jewish historiography. What Yerushalmi brilliantly demonstrated was that the professional historian of the Jews is a modern phenomenon, dating back to Graetz and the mid-nineteeenth century at the earliest. The figure of the historian, it turns out, was another of those things that post-Enlightenment Jews got from their non-Jewish neighbors. And it formed part of a larger European obsession with thinking historically that was closely connected to the rise of mass politics as well. In short it was a new way of relating to the past that was inseparable from a new horizon of expectation in the future.

Not everyone approved. What the Jews did when they embraced the sense of living in historical time, wrote the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, was secularize the messianic promise: tired of waiting for the Messiah, they came to see his arrival as something that could be hastened through political action. It was an attempt to build heaven on earth, and the kind of heaven depended on your politics. It could be via the fulfillment of national dreams, or alternatively by building a socialist or communist utopia in which religious distinctions would lose all meaning. Either way, for Levinas it marked a kind of spiritual and ethical impatience, a misunderstanding of man’s fallen state. Embracing the past, he argues, showed that Jews had lost the capacity to wait. It was this waiting that had given their experience its special character, and in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries they gave up on it.

Whatever we make of Levinas’s view, with its own implicit theology of political detachment, he was surely right that the work of Jewish historians reflected a new consciousness of political entitlement and possibility. Graetz hoped his scholarly tomes would help make the Jews of the German lands valued members of their country. The great Russian historian Simon Dubnow wanted his to pave the way for a different goal: Jewish national-communal autonomy in a multiethnic Russia. What they shared was their relatively nuanced view of anti-Semitism and of Jewish suffering in general. External factors mattered insofar as they shaped things like the emergence of doctrine or the rise of institutions of self-government: They were not to be denied. But they did not in themselves constitute markers of identity or ultimate forces.

Salo Baron, the great pioneer of professional Jewish history in the US (and Yerushalmi’s predecessor at Columbia), felt that even scholars like Graetz harped on the suffering to the detriment of the larger picture. In a celebrated passage now nearly a century old, he inveighed against what he called the lachrymose conception of Jewish history. Baron noted the steady growth in the number of Jews in the world over the centuries (there are few demographics in Schama), and he suggested that one could not dismiss the evidence for accumulating wealth in many Jewish communities as well: such indicators seemed to complicate an interpretation that saw the wider world as a source of endless Jewish grief.

Baron criticized Graetz, but Graetz at least had regarded the French Revolution and Jewish emancipation as the beginning of a new dawn. And Graetz was not his real target: Baron was much more perturbed by the historical fallacies of Zionism. The Zionist view, he emphasized, really set Jewish suffering center stage. It presented the Enlightenment as a false dawn, Napoleon as another species of tyrant, and the nineteenth century as the age not of Jewish freedom and emancipation from the ghetto but of new forms of oppression and persecution. It was, in short, a distortion of history, and not an innocent one either, because it served a very modern claim—the demand for a national homeland for the Jews, preferably in the Middle East.

Influential throughout the second half of the twentieth century, Baron’s attack on the lachrymose conception has recently come under fire from a new generation of historians who have been keen to emphasize the omnipresence of mass violence against the Jews from ancient to modern times. Belonging reflects this trend. In Schama’s telling, Europe suffers from an endemic anti-Semitism that did not dwindle but flourished after the Enlightenment and Napoleon and the rise of nations. The Middle East and the Maghreb get the same grim treatment: Islam’s supposed capacity for coexistence with the Jews, according to Schama, has been overstressed.

There is going to be only one answer for this resilient little people, and we know by now where it will be found. Fusing the political affiliations of his own familial upbringing and those of his Cambridge historian forefathers, Schama’s book takes Trevelyan’s Gladstonian love of small nations and applies it to the Jews. Trevelyan once wrote that a famous work he had written on Garibaldi and Italian nationalism had been “reeking with bias.” Much the same might be said about Belonging: the author’s approach makes clear his deep sympathy not only for “his” people but for a certain Zionist conception of what history owed them.

The result is a saga of Jews against the rest that flattens the tensions and issues within religious groups on either side of the divide. Conflict among Jews gets smoothed away and the persistence of tensions between rich and poor within Jewish communities is downplayed: Schama has always had a soft spot for philanthropists and bankers, and the hatred the poor Jew long felt for the wealthy one is not something he much considers. He also says surprisingly little about the left in nineteenth-century Jewish life, a lot less than he tells us about Marx’s deplorable anti-Semitism. He writes a long and loving concluding account of the emergence of European Zionism; but the socialist visions and dreams that ran across the Jewish world before 1900 are all but ignored.

In fact, Schama writes as though the fin-de-siècle Jewish world was split into just two groups: assimilated upper-crust Jews who had sold out and surrendered to the illusions of European bourgeois civilization and those less ashamed of their roots who luckily stood firm for Zion. A letter he recently co-wrote to The Times of London reveals not only Schama’s Zionism but the view of history that underpins it, its intolerance and its blindspots. The letter was written to deplore the supposed recrudescence of anti-Semitism in the British Labour Party, and in it Schama and his two co-signatories go so far as to imply that anti-Zionism cannot be disentangled from anti-Semitism.* That is quite a stretch. The politics aside—that is to say, the politics of using the charge of anti-Semitism as a kind of silencing device—it is also not very good history. For one thing, Jewish anti-Zionism from both socialist and Orthodox perspectives has been around as long as Zionism itself, and often rested on a perfectly reasonable critique of Zionist premises that had nothing to do with anti-Semitism. (Much the same could be said of non-Jewish anti-Zionism as well.)

Belonging ends with Europe’s assimilated Jews dancing on the edge of the volcano while the hatred bubbles and boils around them. In Ottoman Palestine, Jerusalem the Golden shimmers on the horizon. Only the third volume will tell us whether it is the Promised Land or a further cause of suffering.

-

*

Howard Jacobson, Simon Sebag Montefiore, and Simon Schama, “The Labour Party and Its Approach to Zionism,” The Times (London), November 6, 2017. ↩