Gustave Flaubert’s next best seller after Madame Bovary was Salammbô, a historical novel about a revolt of mercenaries in third-century-BC Carthage. The black novelist Charles Chesnutt saw the Italian film director Domenico Gaido’s adaptation, Salambo, in a Cleveland movie theater in 1915. Chesnutt remembered that when Spendius, the mercenary general’s black lieutenant, came on the screen, a white woman sitting next to him remarked, “Well, look at the coon! He’s a spy and a traitor, no doubt.” The medium of film was still rather new, but the attitudes projected through it were the familiar, vicious ones that Chesnutt, born a free black in North Carolina in 1858, had made it his life’s work to write against.

In 1915, Chesnutt joined the nationwide protests against the distribution of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. In Boston, where the film had its premiere, the black newspaper editor William Monroe Trotter staged pickets, but W.E.B. Du Bois at the NAACP, founded in 1909, wondered if the efforts to stop the film only helped to advertise it. Griffith’s technical achievements were nullified by the film’s being based on the white supremacist novels of Thomas Dixon, Du Bois said. The Civil War battle scenes were one thing, but Griffith glorified the Klan and depicted “the emancipation and enfranchisement of the slave” as “an orgy of theft and degradation and wide rape of white women.” The Birth of a Nation gave a tremendous boost to the popularity of movies. Yet Du Bois thought that “without doubt the increase of lynching in 1915 and later was directly encouraged by this film.”

Booker T. Washington joined calls for The Birth of a Nation to be banned. His “Tuskegee Machine” had enjoyed some influence with Republican administrations, but that vanished with the election to the presidency in 1912 of the Virginia-born Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Washington, who had advocated racial survival through accommodation of Jim Crow practices in the South, said nothing publicly when one of Wilson’s first acts was to segregate federal government agencies in the nation’s capital. Du Bois had supported Wilson’s presidential bid, as had Trotter, who in 1914 felt so betrayed that curtains were going up to divide black clerks from white clerks that he led a delegation to the White House. Wilson had Trotter thrown out.

In 1915, Wilson welcomed Griffith to the White House for a special screening of The Birth of a Nation. He is supposed to have said, “It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” Thomas Dixon, who was also a Baptist minister, was a friend of Wilson’s. Wilson’s father, a Presbyterian minister, had been a Confederate loyalist, and Griffith’s father was a Confederate officer. It turned out that Griffith was the Great White Hope, with his stated intention to make every white American a southern partisan. The film of black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson knocking out his white opponent in Reno, Nevada, in 1910 had been banned everywhere in the South.

In his study Slow Fade to Black (1977), Thomas Cripps points out that Griffith used black people for his scenes showing violent black mobs and incompetent black legislators, but not for black characters, or for scenes with dialogue. Witnesses reported black audiences cursing and weeping at the antics of white actors in black face. White audiences in the South howled for the lynching of black characters on the screen. In a couple of small towns in 1915 white men walked out of theaters after seeing The Birth of a Nation and killed black men. Chesnutt was still writing against The Birth of a Nation in 1917, arguing that its principal villain, a black captain in the Union army, would incite whites at a time when America needed unity.

The film is so offensive that I find myself wanting Abel Gance to be the father of modern cinema, though Napoléon was not made until 1927. It says something about Du Bois’s coolness of judgment that he gave Griffith his due as an innovator. Years later Du Bois recalled the unease caused by the boycott of a racist motion picture:

We had to ask liberals to oppose freedom of art and expression, and it was senseless for them to reply: “Use this art in your own defence.” The cost of picture making and the scarcity of appropriate artistic talent made any such immediate answer beyond question.

The socially cautious Washington was alive to the possibilities of film as an educational tool, as propaganda. In 1910, he collaborated with a black firm to produce a film about the Tuskegee Institute, the school of industrial education he had founded in Alabama in 1881. It opened at Carnegie Hall but was not a success. In 1913, a second film about Tuskegee that he made with another black company failed because tickets cost too much. Washington had also tried, without success, to interest white companies in adapting his best-selling autobiography, Up from Slavery (1901).

Advertisement

In Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era (2001), Jane M. Gaines shows that thirteen black film companies were operating by the end of World War I, although most of them released only one film. According to Gaines, William Foster directed the first black film, The Railroad Porter, a one-reel comedy, in 1913 (other sources say 1912). He stressed the importance of movies to race consciousness and cited cases in which blacks succeeded in having some racist caricatures taken out of circulation. Black producers and directors founded their own film companies out of a desire to counter racist images and enable blacks to see themselves on the screen as they really were. Nevertheless, the noted black photographer Peter P. Jones followed his first film venture, a newsreel about black Shriners, with The Troubles of Sambo and Dinah (1914).1

Blackness was often a source of comedy in American culture. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was first made into a short film in 1903, as a compendium of black stereotypes prevalent since slavery, according to Donald Bogle in Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (1973). A Nigger in the Woodpile (1904), a blackface comedy, is one of those productions from the era when film was not far from its nickelodeon origins. Foster envisioned motion pictures as a thriving industry for black people, and warned that if they didn’t invest in their own films, white people would step in and grab the profits. The millions of dollars The Birth of a Nation was said to have earned at the box office was in itself a news story.

The black actor Noble Johnson starred in thirty-four films for his Lincoln Motion Picture Company between 1915 and 1918, playing mostly ethnic characters—Native Americans, Latinos, Arabs—not black ones. But Universal Pictures, the white studio that wanted him under contract, got him to resign from all-black Lincoln, by then a competitor. In 1916, the Frederick Douglass Film Company produced The Colored American Winning His Suit, and then two more films, one of which was a documentary, Heroic Negro Soldiers of the World War (1919). Emmett J. Scott, Booker T. Washington’s secretary, attempted to make a film in answer to Griffith’s. What began with the title Lincoln’s Dream became The Birth of a Race. After Scott had to bring in white backers, his film as released in 1918 had nothing to do with black progress since slavery and was instead about two white German-American brothers who fought on opposite sides during World War I.

Early black films are periodically screened at cinemas and museums and many of them can now be streamed on YouTube, but an informative, fascinating, and convenient boxed set of them, restored by the Library of Congress, has been issued as Pioneers of African-American Cinema. In its five discs of more than two dozen feature films and extra material, Pioneers covers a great deal. Three slapstick comedies represent the work of the Ebony Film Corporation of Chicago, which may have been white-owned: Two Knights of Vaudeville (1915), Mercy, the Mummy Mumbled (1918), and A Reckless Rover (1918), in which a black man takes refuge in a Chinese laundry and finds an opium pipe. A four-minute fragment from By Right of Birth (1921) is all that remains of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company’s many films. Charles Musser and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart provide helpful essays and notes. The aesthetic, even the subjects, are sometimes remote from us; we need to know what we’re watching and why.

The Pioneers collection includes documentary footage: clips from Zora Neale Hurston’s folklore-collecting trips in 1928 (as well as sound footage Hurston shot in 1940) and Reverend Solomon Sir Jones’s short home movies shot between 1924 and 1928, showing tastefully dressed black families in Oklahoma, their automobiles, and streets of brick houses. In Hell-Bound Train (circa 1930), brilliantly restored by S. Torriano Berry, the evangelists James and Eloyce Gist present a horned, caped devil as the engineer on a smoking locomotive racing sinners to the flames. Dancing is the original sin, leading to drunkenness, unwanted babies, and shootings. However, the party of well-dressed young black people at which the dire consequences of dancing unfold looks like the greatest fun. It’s been helped by a newly created score from Reverend Samuel Waymon, Nina Simone’s brother.

White directors of feature films sometimes took on serious themes of black life. The great black stage actor Charles Gilpin stars in Ten Nights in a Bar Room (1926), in which a man’s alcoholism destroys his family. In the beautifully shot The Scar of Shame (1929), a cultured black man’s fear of his mother leads to the suicide of his lower-class wife.

Advertisement

But the business of film was entertainment, which meant escapism. The Pioneers collection offers two films produced by the Jewish-owned Colored Players Film Corporation. The well-made The Flying Ace (1926), also in the Pioneers collection, is the best-known film by Richard E. Norman, a white director of movies with black casts. Black audiences enjoyed taking time off with a thriller that climaxes in a bicycle, car, and plane chase. The bad cop, the railroad general manager, the dentist, bootlegger, pretty heroine, and dashing aviator are all black. The title cards are not in dialect, and even the comic character, a one-legged veteran, is a hero and catches bad guys.

Not all black directors took the race problem as their subject. Eleven P.M. (1928) is the only surviving film by Richard D. Maurice, an offbeat black filmmaker in Detroit. His is a revenge tale in which a duped fiddler comes back as a dog to bite to death the man who destroyed his family. Toward the end there is a scene in which the fiddler, played by Maurice, who sort of looks like James Cagney, is shown as having a dog’s body. Or maybe that was a dream about reincarnation had by a young and handsome black reporter we see whose copy was due at eleven o’clock.

Oscar Micheaux, the most prolific of early black filmmakers, is the best known because more of his work survives than that of any other black director from the period. Born in 1884 into a large, proud family on a southern Illinois farm, he went from shoeshine boy in Chicago to Pullman porter. In 1905, he purchased land in the Rosebud Sioux reservation in South Dakota, eventually acquiring five hundred acres. It was harsh, isolated country. When Micheaux lost the land to foreclosure in 1912, he turned to writing, producing three autobiographical novels, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer (1913), The Forged Note: A Romance of the Darker Races (1915), and The Homesteader (1917), publishing the last two books himself.

The Lincoln Motion Picture Company approached Micheaux about securing the rights to The Homesteader, but the ever-ambitious Micheaux wanted to direct the film himself. The son of former slaves, he subscribed to Booker T. Washington’s ideas concerning economic self-reliance for blacks. His Micheaux Book and Film Company raised money from small investors, largely white farmers, and he released The Homesteader in 1919. Micheaux was self-taught as cameraman and director. Everyone was. No copy of the eight- or nine-reel film—then the longest film made by a black director—is extant.

The film is lost, but we know the plot from the novel. The Homesteader is a convoluted tale of love lost and found under the heavy snows of the prairie. In fiction, Micheaux could correct life. His marriage had ended when his wife’s domineering father took her back to Chicago after she suffered a stillbirth. She’d found homesteading unendurable in any case. In The Homesteader, on the other hand, when white-looking Agnes learns that her mother had “Ethiopian” blood, she decides to “share what is Ethiopia’s” and returns to Jean Baptiste, the strong, vigorous colored farmer who’d refused her when he thought she was white, though he was in love with her.

Micheaux’s “photoplay” The Homesteader was heavily advertised in black Chicago. A tenor sang and an orchestra played at each showing of his “silent art.” This was a few months before four days of race rioting in Chicago, during which thirty-eight people died. Riots would erupt in two dozen other American cities in the Red Summer of 1919. Two hundred blacks trying to form a labor union in Elaine, Arkansas, were massacred. Seventy-six black men were lynched elsewhere in the South that summer. Fear of more racial violence may have kept black people from movie houses, and whites did not go to The Homesteader after all.

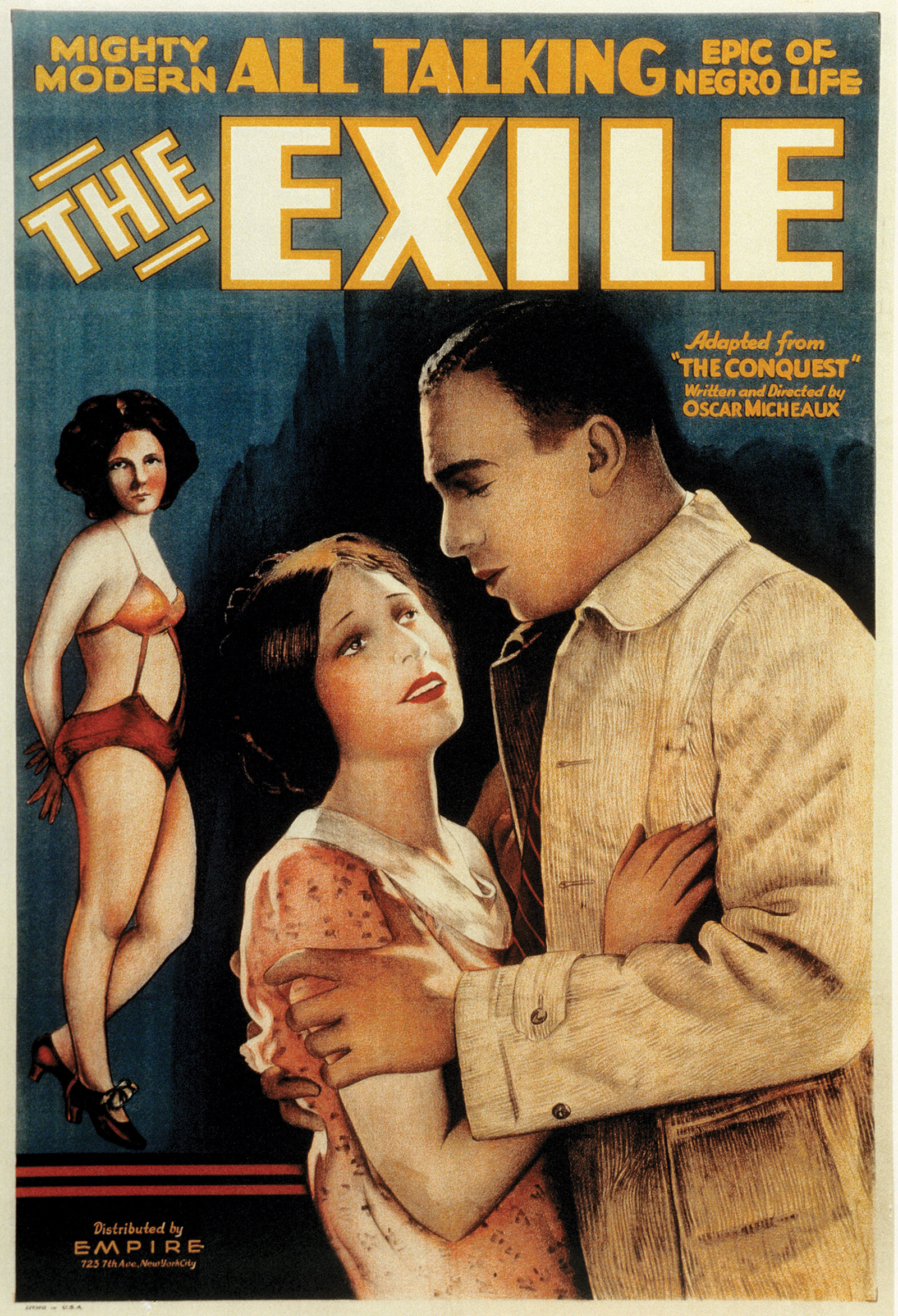

Micheaux directed twenty-two silent films. Copies of his earliest surviving films were found not long ago in two European archives. He survived the crash of 1929 and was the only black silent filmmaker to move into talkies, producing fifteen films between 1931 and 1948. Maybe thirteen of his films in all survive. Oscar Micheaux and His Circle: African-American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era, the catalog for a seven-part program of films shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 2001, contains a complete filmography of his silent films, using reviews to reconstruct lost work in surprising detail.2

The three surviving silent films by Micheaux are in the Pioneers collection. In his second, Within Our Gates (1920), he moves away from the Booker T. Washington–like race neutrality of his novels. The oldest surviving feature-length film by a black American, Within Our Gates depicts in flashback the lynching of the heroine’s loving adoptive parents and her near rape by her biological father, a white man. It is considered Micheaux’s rebuttal to Griffith, showing the innocence of lynched blacks and just who had done the raping in American history, as Toni Cade Bambara notes in a PBS documentary, Midnight Ramble: Oscar Micheaux and the History of Race (1994). Micheaux also shows the injustice of sharecropping, the importance of independent black institutions, and the way racism in the South cut across class lines among whites. Within Our Gates was banned in southern states as incendiary. (Whereas Micheaux’s mob constitutes hardly thirty extras, a crowd of thousands cheered the burning of a seventeen-year-old black boy in Waco, Texas, in 1916.) But even in black Chicago the film was not a success.

The Symbol of the Unconquered: A Story of the Ku Klux Klan (1920), like all of Micheaux’s work about the Northwest, extolls the frontier as a refuge for black men. It turns the Klan into land thieves and features a self-hating black villain who passes for white and beats his own mother to death. Love triumphs once the rugged, light-skinned black settler realizes that the lovely new neighbor he’s been fighting for is black, not white. Another film Micheaux produced in 1920, The Brute, about a boxer, is lost. Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence in Oscar Micheaux and His Circle say that in the film Micheaux condemned racketeering and the abuse of women. The roles of black women in these films are not much different from the roles of, say, Mary Pickford in the same era. Women needed to be saved. But of course not even light-skinned black women had been rescued in anyone’s film melodramas before the advent of race films.

Paul Robeson made his film debut in Micheaux’s Body and Soul (1925), a tale of struggle between good and evil. Robeson plays twin brothers, a sociopath and a noble inventor. He often had to switch characters within minutes during filming, and scenes were done in one take, with little rehearsal, so tight was Micheaux’s budget. Robeson is an animating presence, and not much more can be said for the melodrama—like Borderline, an experimental film Robeson made with H.D. in Switzerland in 1930. Both Thomas Cripps and Donald Bogle have speculated that the Body and Soul we have may show the effects of censorship and hasty editing, that it is missing scenes and only suggests the original. Charles Musser, however, concludes that the one copy in existence seems reasonably complete. He interprets the film as a reworking of two early Eugene O’Neill race plays, as well as of a play by the then well-known Nan Bagby Stephens.

Alain Locke’s anthology The New Negro (1925), that defining moment of the Harlem Renaissance, talks about art, novels, poetry, drama, and music of black people, but has nothing to say about black America and film (or photography). Moviegoing for blacks in Jim Crow times often meant sitting in segregated balconies—the buzzard’s roost, nigger heaven. In the heyday of race movies in the 1920s, black vaudeville houses became movie theaters, but even so, only three hundred of the nation’s estimated 20,000 movie theaters catered to black audiences. Movies were collaborations, costly to make, and not entirely trusted by black filmgoers because they were such common vehicles of racist expression.

Though the black press supported Micheaux’s early efforts, he came in for criticism from black people who objected to his drunks, gamblers, corrupt ministers, thieves, and murderers. Representations of lowlife did not fit with racial uplift, the goal of creating positive images of black people. Black novelists and black playwrights were under even more pressure when it came to the content and tone of their work, because they had the prestige of high culture that film didn’t as yet. At the same time, realists in black literature were driven by their determination to tell the truth about racism, social conditions, and American history.

Strangely absent in Micheaux’s work is the atmosphere of the Great Northern Drive, the mass migration that would see half a million blacks leave the South for the North during World War I alone. The romance for him was the West, not the big city. Then, too, his literary sources were pre-Harlem Renaissance novels, starting with his own. In 1924, Micheaux made an adaptation of the white novelist T.S. Stribling’s best seller Birthright (1922). Two hours long, it is now lost, but was said to have followed closely the novel’s plot concerning the travails of an educated black man who has come home to the South to teach black youth. Stribling thought of his work as explaining black people in the setting of their degraded environment. In 1924, Micheaux also adapted The House Behind the Cedars (1900), Charles Chesnutt’s novel about a black girl passing for white who falls in love with a white man. The lost film had a happy ending, unlike the novel, and Chesnutt was unimpressed.

The coming of sound spelled the end of the black movie, because white film companies saw black musicals as a lucrative market. Some blacks thought that silent film deprived Paul Robeson of his greatest asset, his voice, while some black critics now see singing and dancing as the slippery road that led back to the old racial stereotypes. Josephine Baker in La Sirène des tropiques (1927) is dancing furiously while being ogled by white men in black tie in the wings. But silent films were never silent; the musical accompaniment could make a difference, and most of the early black films of the Pioneers collection have had new scores commissioned.

Oscar Micheaux in his silent period kept his faith in his ability to make his own opportunities, even as segregation intensified. His early films are about color consciousness, whether about hierarchies within black communities or interracial romances that turn out not to be interracial because the woman has one drop of black blood and under US law that was enough to make her black. They may not have the disciplined construction of other directors’ work, but they have a kind of mystery, are seemingly about more than he can say, as if in the pioneering days the lines blurred easily. He often had light-skinned black actors play white characters.

Some argue that while Micheaux’s films may be technically flawed, it is more important that he was a one-man black outfit, that he wrote, directed, produced, and distributed his films himself. Micheaux stopped making movies during World War II and wrote three more novels based on his prairie experiences. But he got right back to it when he could. His last film—another remake of his first novel—came out in 1948. He died in 1951. His sound films tended to be reworkings of his silent films, and not as good. His time was gone and the medium had changed around him.

In 2014, the Museum of Modern Art screened Lime Kiln Club Field Day (1913), a black comedy made by the Biograph Company, a white company, but never released. It starred the black musical legend Bert Williams. Williams’s character gets the girl and kisses her at the end. Most films of that time did not show blacks at leisure or being intimate. Williams won hearts in America and Europe playing a sad man, but he was still a black man performing in blackface. “Your self image is so powerful it unwittingly becomes your destiny,” Micheaux said.

This Issue

April 19, 2018

A Mighty Wind

The Question of Hamlet

More Equal Than Others

-

1

See Anna Everett, Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, 1909–1949 (Duke University Press, 2001). Everett raises the question of how much control Jones had over his own company. ↩

-

2

See also Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence, Writing Himself into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films, and His Audience (Rutgers University Press, 2000). ↩