One might start with his tomb, which he had built on the islet of Grand Bé, just off the Breton port of Saint-Malo, facing the tempestuous sea that was the companion of his first years. He was adamant that it should have no inscription, no name, no date, only a simple cross: “The cross will tell that the man at rest was a Christian: that will suffice to my remembrance.” It is typical Chateaubriand in its passive-aggressive insistence on an extraordinary monument (it took years of negotiation with the local authorities to permit the gravesite) along with the claim of anonymity and Christian humility. Throughout his Memoirs from Beyond the Grave (Mémoires d’outre-tombe), the claims of privacy, retreat, and submission rub against the assertion of greatness. The “enchanter,” contemporaries called François-René, Vicomte de Chateaubriand, in response to his fluid, mellifluous, eloquent, and often cutting style. The Memoirs, designed to be posthumous, echo the grandiosity of his tomb but are distinctly more interesting.

There is a moment in book three of the Memoirs when Chateaubriand in 1817, in the park of his friend Madame de Colbert-Montboissier’s château—reduced by the French Revolution to two modest outbuildings—is meditating on the collapse of Napoleon’s empire, fallen like so many others over the centuries, and hears the song of a thrush. “This magic sound brought my father’s lands back before my eyes in an instant. I forgot the disasters I had only recently witnessed and, abruptly transported into the past, I saw again those fields where I so often heard the thrushes whistling.” It’s a Proustian moment of recovery of the past, as readers have often noted. Also a Rousseauian moment, very much like that in book six of the Confessions when Rousseau comes upon a periwinkle flower in bloom and is transported back to his idyllic happiness with Madame de Warens at the country house Les Charmettes. The play of memory within the present moment has the same resonance in all three writers. What makes recollection important is its transformative function within passing time, the ability it gives to hold in the mind simultaneously two strata of time, to straddle them as it were, and live for an instant in both.

Chateaubriand again and again tells us the date on which he is writing reflectively about the past as he delves into his memories, giving an effectively stereoscopic vision of his life and times. And extraordinary life and times they were. Born in 1768 into a noble Breton family that had gone from pennilessness to a modest affluence because his father owned ships engaged in the slave trade, he grew up largely in the gloomy castle of Combourg, as his taciturn father nightly paced the floor, disappearing into shadows at the end of the great hall and then reappearing, always without a word.

His evocations of a solitary childhood are memorable. As a very young man he joined a military regiment, was presented at the court of Louis XVI at Versailles, and prepared to enter the Order of the Knights of Malta. Then came the convocation of the Estates General and the beginnings of the Revolution. His reaction was to escape to America, ostensibly to discover the elusive Northwest Passage, though in reality his trip seems to have taken him on a loop from Philadelphia up through New York and west to Niagara Falls, then (perhaps) down to Pittsburgh and the Ohio River, then back east through Kentucky; since he embellished his itinerary considerably, suggesting that he descended the length of the Mississippi, for instance, it’s hard to trace it exactly. It’s also hard to know whether the interview with George Washington he reports ever took place or is simply a rhetorical device to contrast the noble Washington with the tyrannical Napoleon.

Spending the night in a farmstead while traveling back to Philadelphia, he claims to have happened to pick up a newspaper that told of the French king’s attempted flight that ended at Varennes, in eastern France, and Louis’s return to Paris as a fallen monarch, prisoner of the Revolution. This sparked Chateaubriand’s return to France and his decision to join the émigrés in the “Army of the Princes” that had formed in Koblenz in preparation for an invasion of the revolutionary homeland—but not before his family married him off to a young Breton, Céleste Buisson de la Vigne, who was supposed to be wealthier than she in fact was, and whom he promptly abandoned, though they did live together reasonably peacefully later in life. He was seriously wounded at the siege of the French fortress of Thionville, then made his way to England, arriving in January 1793, a few days before Louis XVI died on the scaffold. His elder brother and sister-in-law also were guillotined; his wife, sisters, and mother spent months in prison. Chateaubriand spent the next seven and half years living in penury in London and elsewhere in England, teaching French for a living; he returned to France only in May 1800, under a false name since he was still on the list of proscribed émigrés.

Advertisement

But for all his sense of living in a time out of joint that was destroying the class and the beliefs to which he was born, Chateaubriand managed to have an impeccable sense of timing when it came to publication. His Génie du christianisme, a celebration of the aesthetic and spiritual contributions of the church, was published in 1802, just after Napoleon signed his concordat with the Vatican, which returned the church to its central place in the French state. It was a success, and also suited Napoleon’s purposes so well that Chateaubriand was made secretary to the French legation in Rome. There he quarreled constantly with the French ambassador (Napoleon’s uncle) and was soon shifted to a less important diplomatic post in the Valais, in Switzerland. But in the meantime came Napoleon’s judicial murder of the duc d’Enghien, a Bourbon prince accused of conspiring against the state, which caused Chateaubriand to resign.

But he would be back. After his trip to the Middle East in 1806 and the publication of his Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem in 1811, he was ready, as Napoleon’s empire began its collapse in 1814, with a pamphlet called De Buonaparte et des Bourbons, a vigorous defense of legitimate monarchy against the usurper, whose name is here spelled in Italian form (as it generally was by his detractors) to suggest that he was a foreigner as well as an unmannered upstart and a tyrant who had destroyed traditional French liberties in the arbitrary police state he built.

Henceforth Chateaubriand would be the expositor and theorist of monarchical legitimacy as tempered by constitutionalism: he believed in scrupulous observance of la Charte, the constitution granted by the king to his people in 1814. He was too smart to believe that the brothers of Louis XVI who ruled France during the Restoration that followed the fall of Napoleon, first Louis XVIII then his reactionary younger brother Charles X, were the best and the brightest. What mattered was that they reached back to the ninth century, in a line of kings that represented a living past that gave the nation its roots and its identity. Monarchy was the guarantor of both social stability and individual freedom. He would, after the last Bourbon king went into exile following the Revolution of 1830, remain loyal to the Legitimist pretender, the comte de Chambord, who ought to have become King Henri V but never did.

The Vicomte de Chateaubriand, as he now could openly be, largely flourished during the Restoration, becoming a peer of France, minister plenipotentiary in Berlin, then ambassador to London, and finally minister of foreign affairs. When he fell from that height, he was named ambassador to Rome. Out of government more often than in, he proved an effective “publicist,” as the French called those who made opinion through the newly powerful press. It was indeed freedom of the press—repeatedly subject to regulation and censorship in these years—that became his particular cause. Without a free press, he understood, no French regime could be prevented from acting tyrannically. Chateaubriand founded and edited for a time Le Conservateur, conceived in ultra-conservative opposition to Benjamin Constant’s liberal La Minerve française. The Revolution of 1830 and the ascension of Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, from a branch of royalty not in the normal line of succession, to the throne as “king of the French” led to his resignation from public life, but not before a resounding speech in the Chamber of Peers denouncing the break in the legitimate line of monarchs.

After this, it was mainly writing, especially the Mémoires d’outre-tombe, which run to forty-four books, some two thousand pages in the Pléiade edition. The new English unabridged translation by Alex Andriesse brings us books one through twelve, covering the years 1768 to 1800, which may be the best of the Memoirs—childhood, youth, the American adventure, then combat with the Army of the Princes, his wounding, and his years in England, including the poignant love idyll with the young Charlotte Ives that is movingly reprised in W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn.

What it doesn’t include is Chateaubriand’s public and political life, or his impressive love life with many of the great beauties and wits of his time, culminating in the ravishing Juliette Récamier. He seems never to have been long without a mistress. But Chateaubriand has an aristocratic discretion about his loves and his private life in general. If Rousseau understood that one of the challenges of confessional literature lay in a sense of risk-taking—revealing what is most intimate and especially shameful—Chateaubriand reveals little. The virtues of the Memoirs lie elsewhere, in his skill as a narrator and as a trenchant judge of his contemporaries. Whatever one’s judgment on Chateaubriand’s ego and his politics, the Memoirs are good reading.

Advertisement

The Chateaubriand who speaks, as he puts it, “from the depths of my coffin” differs considerably from the one who made a sensational entry into the literature of his time as the early voice of French Romanticism that swept away neoclassicism in favor of a reenchantment of the world. Atala and René are narratives that belong to the Christian apology, Le Génie du christianisme—which set out to appeal to our religious convictions by way of the imagination—but have led their own lives. Chateaubriand presented René as a kind of counterexample, an illustration of what he called “le vague des passions”: a state of passion without an object, a full heart in an empty world. In René’s words: “Alas! I seek only an unknown good, its instinct pursues me. Is it my fault if I find limits everywhere, if that which is finite has no value for me?” René cries aloud “with all the force of my desires” for “the ideal object of a future flame,” only, in his disappointment, to long for what would ravish him from life: “Come quickly, wished for tempests, to take René away to the space of another life!”

René’s passion is matched by that of his sister Amélie, who upon taking the veil as a nun reveals the “criminal passion” she harbors for her brother. Romantics have a tendency to postulate fraternal-sororal incest as the perfect love, the soul-sister and brother as lovers—though the love rarely is consummated. But of course the emptiness in René’s soul could only be filled by a less transient object. He ends up in America, telling his sad tale to the Natchez Indian Chactas and the missionary Father Souël, who takes him to task: “presumptuous young man who believed that man can be sufficient unto himself!”

As Chateaubriand was apparently discovering in his own life, only faith could bring a measure of psychological peace. His account of his conversion is succinct: upon learning of his mother’s and sister’s deaths, he tells us, “I wept, and I believed.” Things were possibly more complex and socially motivated than that: a hankering to return to religion was widespread after the Revolution, though certainly Chateaubriand himself was one of its first and most effective promoters. Yet the fictional figure René took on a life of his own as a pre-Byronic figure, fully realized in the wandering Childe Harold. (Chateaubriand was bemused and a bit jealous of the younger Englishman’s European success.) Atala, on the other hand, was published in advance of Le Génie du christianisme in 1801 (the same year as Wordsworth’s famous preface to the Lyrical Ballads) and quickly ran through several editions.

“It is from the publication of Atala that my reputation dates: I ceased to live for myself and my public career began,” he noted late in life. If much of Le Génie du christianisme is insipid reading today, Atala still speaks to us as some sort of authentic document of European “American Indianism,” a tragic romance of the forest. It is marked by an elegiac regret over the loss of the vast French empire in America, a kind of new Eden lavishly evoked in the opening pages of the tale, including the description of the banks of the Mississippi: to the west marked by plains rolling to the horizon covered by herds of three or four thousand buffalo, while on the eastern shore the rich foliage of magnificent trees provides the habitat of an abundance of species, including “bears drunk from eating grapes, who teeter on the branches of elms.”

This abundant, generous, luxuriant nature, some of it directly observed by Chateaubriand, some of it derived from written accounts of early explorers, includes the sublime spectacle of Niagara Falls, a sight where “pleasure mingles with terror.” He offers as well some quasi-anthropological and largely admiring observations of Indian life, gleaned mostly from the week he spent with the Onondagas on his way to the falls. There is a tinge of Claude Lévi-Strauss in Chateaubriand’s discovery of a savage state not quite yet—though soon to be—adulterated by the European observer.

But the one moment of stable happiness reported in Atala comes with those Indians Christianized by Father Aubry who have taken up farming, in “the primal marriage of Man and the Earth.” Aubry’s colony resembles Rousseau’s “société naissante,” the first emergence of cooperative humanity from the state of nature that, rather than the state of nature itself, he considers to be the ideal moment in human evolution, before the coming of private property. Ideal, yet inevitably transitory: the progress of civilization will bring corruption, the creation of artificial needs and desires, the demarcations of haves and have-nots, and the heavy hand of the law invented to prevent the victims of inequality from taking back what they have lost. But Chateaubriand’s Rousseauism comes to be infiltrated by the lurking requirements of Christian orthodoxy: Atala, like René, leads to sermonizing.

Still, it is all more ambivalent and interesting than orthodox. The language of Indianism here responds to Rousseau’s claim that the first speech of mankind was in fact song, chant, emotional outburst in lyrical form. Language is figural at the outset and remains so today, though in submerged and unrecognized fashion. As he goes about creating Indian-speak, Chateaubriand explicitly calls upon his rich knowledge of Homer and the Bible, so that a young brave going to meet his beloved uses a language that resembles the Song of Songs, and at other moments we hear something like the verses of the Psalms, while warriors confront one another with Homeric epithets.

To Chateaubriand’s stylistic sources one needs to add Ossian, the “Celtic bard” created by James Macpherson in the eighteenth century who nonetheless to generations of early Romantics offered the very model of a “naive,” authentic folk poetry. The language of natural man in his (menaced) Eden that Chateaubriand invents appears to us today both an overluxuriant hothouse plant and an eloquent, at times moving creation of an alternative to the languages of Europe when it was consumed by political conflict. The man who escaped France on the verge of the Terror sought to bring back some message of natural eloquence from the New World.

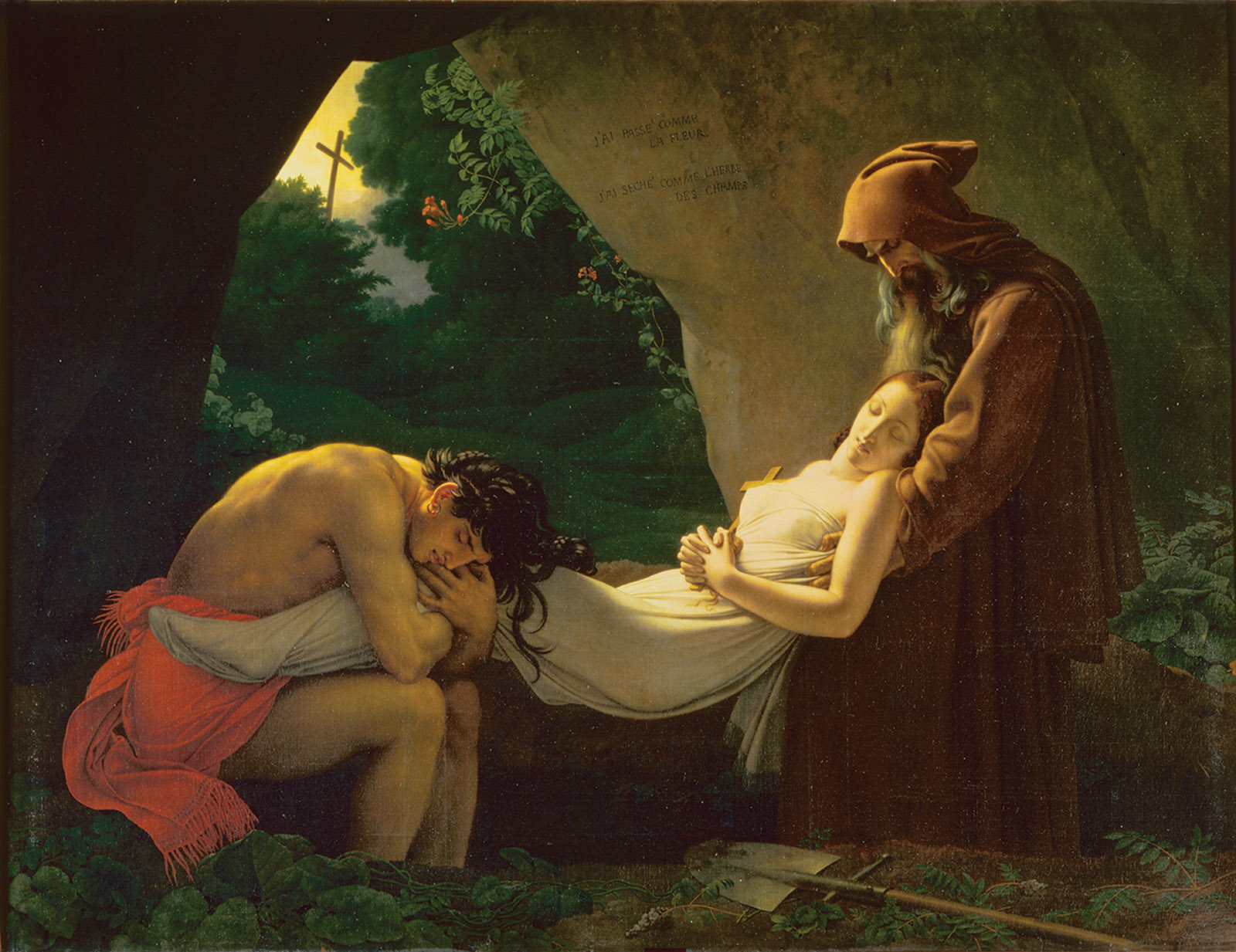

Atala remains Chateaubriand’s most effective fictional work. It tells the story of Chactas, the Natchez Indian captured by his rivals and saved by Atala, seemingly a chieftain’s daughter but really sired by a Spaniard and made a Christian by her mother, who on her deathbed forced Atala to vow to remain a virgin. It turns on an irreconcilable conflict of religion and “nature” that can only end in Atala’s death. Father Aubry will explain that her vow represents a misunderstanding of true religion—but his words come too late, since she has taken poison rather than give herself to Chactas, whom she desires with a passion that is fully reciprocated. She is promised instead to the eternity of God’s love. Her funeral, for which she is wrapped in the last remnant of linen Aubry has preserved from Europe, under a natural stone bridge, to Aubry’s chants from the Book of Job, creates a theatrical tableau that called for illustration—and found a response in one of Anne-Louis Girodet’s masterpieces.

An epilogue returns us to the narrator who has heard this tale transmitted over the years by the Seminole Indians: we learn of the death of Chactas, of Father Aubry, of René who became Chactas’s friend and interlocutor. An Indian woman then shows the narrator the ancestral bones of Chactas that her tribe carries with it. And so the narrator concludes:

Ill-fated Indians that I have seen wandering in the deserts of the NewWorld, with the ashes of your ancestors, you who offered me hospitality despite your misery, I could not repay your kindness today since I wander, like you, at the mercy of mankind; and less happy than you in my exile since I have not carried with me the bones of my fathers.

Here the narrator returns us to his exilic state, driven out from his homeland and his patrimony, and at the same time acknowledges that the American Indian has fallen from noble savage to something like exile within his native land, the victim of those forces of civilization, including Christianity, sent to “save” him.

Chateaubriand’s state of unhappy ambivalence is one we may recognize and find sympathetic—more so than the Christian certainties that are the message of the Génie and much of his other work. He revisited the American Indian in the prose epic novel Les Natchez, published only in 1827, and also undertook a Christian epic novel in Les Martyrs (1809). He satisfied both his epic and his religious imaginative impulses in his prose translation of Milton’s Paradise Lost, published in 1836 and still read today.

When in his seventies, Chateaubriand at the behest of his confessor wrote the Life of Rancé, about the worldly seventeenth-century aristocrat who converted to become the severe reformist of the Trappist Monastery. It is a book that breaks wildly with the hagiographic tradition in a fractured, digressive narrative that Roland Barthes admired as “paratactic.” Chateaubriand gives himself license to evoke all his favorite figures from the century of Louis XIV and to pass judgments on his own contemporaries as well, in a final meditation on life and death.

He intended the Memoirs to appear only fifty years after his death. But with the end of his public career he fell into straitened circumstances, and was obliged to sell the rights to the book to a kind of limited stock partnership. As he lived on and on, until nearly age eighty, Émile de Girardin, publisher of the newspaper La Presse, bought the rights, and planned to begin running the Memoirs as a serial as soon as Chateaubriand breathed his last. Powerless to control what happened beyond the grave, Chateaubriand protested—and revised, pruning some material judged indelicate and inflammatory. The Memoirs published in La Presse, and almost concomitantly in book form, had little initial success: generations nourished on Atala and the Génie found them arid and unpoetic. This work of an old man was curiously in advance of its time. It was only about fifty years after his death—and with a new edition—that the Memoirs came to eclipse most of his other work.

As Anka Muhlstein points out in her graceful introduction, Chateaubriand has been a stylistic model for many later writers: Victor Hugo (who at an early age declared he would be “Chateaubriand or nothing”), Baudelaire, Proust. In our time, Paul Auster in The Book of Illusions singles out for praise the “fierce, breathtaking image” of Queen Marie-Antoinette’s gracious smile directed at the young Chateaubriand at Versailles in 1789, with a mouth so notable that (“horrible thought!”) it enabled him to identify her skull when it was pulled from the common pit during the Restoration, in 1815, more than twenty years after her execution. An impressive swoop through time, even if one doubts the possibility of recognizing a skull from the once smiling lips: a rhetorical rather than a literal truth.

Charles de Gaulle admired Chateaubriand the historical thinker: in the Memoirs he found a keen analyst of the future of European societies, someone who asked himself what would happen if peoples threw off religion and the social hierarchies it underwrote, and discovered the scandal of vast social inequality without the means to address it. Chateaubriand’s younger contemporary Henri Beyle, aka Stendhal, on the other hand, detested him: he found the exalted style of the Enchanter a lie, its bombast (“emphase”) a way to cover up rather than reveal the truth. In part, this is because they were reading different texts: Stendhal, who died in 1842, could not know the Memoirs. But I find the two readings, that of the nationalist Catholic statesman and that of the skeptical novelist, to be both on target. One can still read the Enchanter, even in a spirit of disenchantment with the sometimes purple prose, and the intrusive ego that often seems to detract from his remembrance of things past.

As for that island tomb off Saint-Malo: the young Gustave Flaubert, his romanticism not yet fully tamed, on a walking trip in Brittany the summer before Chateaubriand’s death stood in contemplation before the granite slab covering the grave:

He will sleep beneath it, his head turned toward the sea: in this sepulcher built on a reef, his immortality will be as his life, deserted by others and surrounded by tempests.

This Issue

April 19, 2018

A Mighty Wind

The Question of Hamlet

More Equal Than Others