In the conventional political history of Sino-Soviet relations, 1926 and 1927 were years of increasing strain. Stalin and the Comintern supported an alliance formed in 1923 between China’s nationalist Kuomintang party (KMT) and the Chinese Communists to oppose the European “imperialists” and the warlords who dominated northern China and unify the country. But the KMT was split between pro- and anti-Communist factions, and there were divisions within the Soviet leadership about the alliance as well: Stalin’s great rival Leon Trotsky opposed it.

Things looked simpler in Moscow, however, to those outside the Politburo. The Soviet public, reading in newspapers about the heroic struggle of Chinese revolutionaries against imperialism, gathered that a great victory was close, and this seemed to be confirmed when Chiang Kai-shek’s KMT forces entered Shanghai in March 1927. “Shanghai Has Been Taken!” trumpeted the headline on the front page of Pravda. The KMT and the Communist-led Shanghai workers were said to have formed a triumphant alliance and declared a general strike “in honor of the nationalist forces.”

According to Elizabeth McGuire’s Red at Heart, this was the heyday of the Sino-Soviet romance, when young Chinese students fell in love with Russia and revolution, not clearly distinguishing between the two, and strangers on Moscow streets blew kisses at them. Sergei Tretiakov’s new anti-imperialist drama Roar, China! was playing at Moscow’s Meyerhold Theater, and the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky “bawled out/…louder/than the trumpets of Jericho” his solidarity with the Chinese revolution.

Then came disaster. In the “Shanghai massacre” of April 1927, Chiang turned on the Communists, killing and arresting many, and the fledgling Chinese Communist Party, isolated and discredited, had to go underground. It was a terrible blow for the Moscow-led Comintern and the Soviet leadership, both of which were deeply invested in the Chinese struggle—potentially the first big gain for world revolution since the disappointing fizzling of revolution in Western Europe after World War I. Stalin, personally responsible for the Chinese Communist strategy of working for revolution from within the KMT rather than against it, suffered a humiliating setback. The Soviet public was disappointed, and Trotsky, who had criticized Stalin’s China strategy, was proven correct. Many Chinese Communists were disillusioned with Moscow, but the disillusionment went both ways. In Moscow, one of those Chinese students who had been feted just days before had a tomato thrown at him.

McGuire takes the idea of a Sino-Soviet romance seriously, indeed literally: Red at Heart is about Chinese and Russians falling in love with one another, the children they had, and the complications that ensued. In the language of current academic fashion, her book is a contribution to the history of emotions. As she points out, “marriage” and “divorce” are terms often used metaphorically in discussions of international relations, and particularly in reference to the Sino-Soviet connection. Why not take the metaphor literally and investigate the real-life feelings, couplings, and uncouplings of individuals?

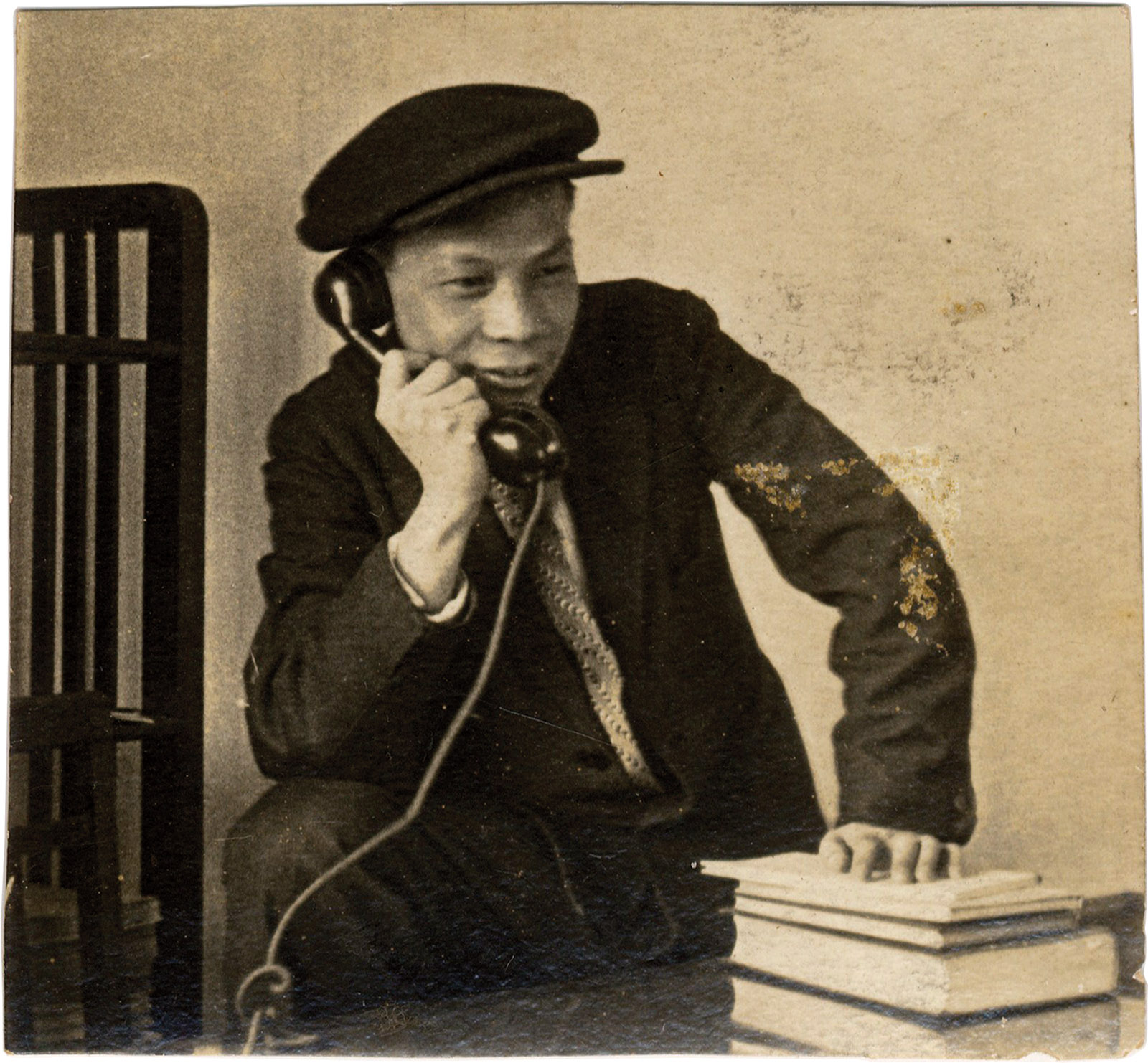

McGuire’s cast of characters is large. Some of them appear only fleetingly, in brief affairs that produce children who grow up in Soviet orphanages. McGuire has tried to make it easier for us by weaving some central figures through her history, which covers the 1920s through the 1950s. One such character is Qu Qiubai, an early publicist of revolutionary Russia in China, who came to revolution through Russian literature and fell in love (platonically) with Sofia Tolstaya, Leo Tolstoy’s granddaughter, on his first visit to Russia. Then there is Xiao San, a childhood friend of Mao Zedong’s in Hunan, who moved to Moscow in 1922 via France (his pen name, Emi Siao, was a tribute to Zola). Siao became a poet when he saw that one was needed to represent China at Soviet-sponsored international writers’ gatherings. For decades he served as a cultural middleman between the Soviet Union and China.

Liu Shaoqi, later to become Mao’s first deputy as secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in the People’s Republic of China until his fall during the Cultural Revolution, had also studied in Moscow in the early 1920s. His mood there, in one account, was “romantic and depressed.” Nevertheless, he later sent two of his young children to be educated in the Soviet Union. After graduating from university, they married respectively a Russian and a Spanish resident of Moscow before their father called them back to China after the victorious revolution in 1949.

Liu’s children were among the many offspring of Chinese revolutionaries who grew up in special Soviet children’s homes. These institutions had kind teachers and caregivers, and were much better provisioned and run than standard Soviet orphanages; still, that is what they were. In the late 1920s, the international children’s home was in Vaskino, a village forty-five miles south of Moscow. In the 1930s, most of the children from Vaskino moved to a new home in Ivanovo, known as Interdom and run by the Comintern’s Organization for Assistance to Revolutionaries. The students there included sons and daughters of Comintern head Georgii Dimitrov; future East European Communist leaders Mátyás Rákosi, Josip Broz Tito, and Bolesław Bierut; the Spanish civil war heroine Dolores Ibarurri; and the American Communist Eugene Dennis. The nearly eight hundred children educated at Interdom between 1933 and 1950 came from forty different countries. At 15 percent of the total, Chinese children made up the largest single group, but like the rest, they were brought up in Russian, with no formal instruction in their native language, and taught by Russian-speaking Soviet teachers. Most of them seem to have ended up as Soviet patriots, even if as adults they did not accept the offer of Soviet citizenship.

Advertisement

The Interdom story—on which McGuire plans to write a separate book—sometimes threatens to overwhelm the story of adult revolutionary romance that is at the center of Red at Heart. It is startling how many Chinese revolutionaries casually dropped off their children for years on end. Vova, the unintended child of two Chinese revolutionaries, arrived at the orphanage after living for a short period with the labor agitator Li Lisan, a subsequent lover of his mother’s; “as Vova understood it, he wasn’t exactly abandoned; his parents were just too busy for him and had never really been a family in the first place.”

Tuya, daughter of Qu Qiubai’s wife by a previous husband, lived for a while with her mother and Qu in the Lux Hotel in Moscow. When the adults went on vacation in the Crimea they deposited her in a children’s home—an ordinary Soviet one at first but then, to her relief, at Vaskino. Emi Siao left his son there for a few months, though the boy was subsequently retrieved by his Russian mother after her separation from Siao; and Siao’s third wife, a German photographer named Eva Sandberg, would later do the same for their two children.

Sun Yat-sen University (also known as Chinese University) in Moscow, where most of the young male and female Chinese revolutionaries in the Soviet Union studied in the second half of the 1920s, seems to have been a hotbed of sexual activity. This was partly, in McGuire’s account, because the sexual aspect of revolutionary liberation was already prominent in the consciousness of young Chinese radicals, who were rebelling against stifling conventions of family life such as the subjugation of women and arranged marriages. It also surely reflected Soviet mores of the swinging 1920s, regardless of the disapproval of Lenin and others in his middle-aged Bolshevik cohort.

But Sun Yat-sen University seems to have presented an extreme case of sexual license, which McGuire attributes partly to its rector, the cosmopolitan Karl Radek. At the height of his affair with the legendarily beautiful Russian revolutionary Larissa Reisner, Radek “encouraged the students to follow his lead in their personal lives. At first there was no co-ed dorm, so Radek designated a special room, supposedly for husbands and wives. It was clear that the room was there for any couple who might wander into it.” Of course all this promiscuous love-making prompted some puritanical responses. As one female student complained, “Everyone is pairing up. It’s really tiresome. When they’re living together they inevitably have children,” a process sometimes described as “making little revolutionaries.”

Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya, was called in to explain to the Chinese students that while “communists needn’t be puritans,” they should “avoid play and abuse in love.” In an informal meeting with female students after her talk, she suggested that instead of having repeated abortions (legally available in the Soviet Union in the 1920s), they should “give birth to their babies and leave them in Russian children’s homes,” which was exactly what many of them went on to do. Much of the Soviet public, along with some party leaders, was unhappy with the sexual license that young revolutionaries had embraced. The official Soviet approach to sexual mores became more censorious in the 1930s—Stalin introduced a prohibition on homosexuality and a ban on abortions—but Moscow’s Chinese students did not seem to change their behavior much in response.

Politics as well as sex caused problems. In the late 1920s, the Soviet Politburo was riven by factional fighting as Stalin consolidated his leadership and defeated the left opposition of Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev. These political struggles had an impact on Sun Yat-sen University. Radek, who had supported Trotsky, was removed as rector. His successor, the hitherto obscure Pavel Mif, gathered a team of loyalists, including the future general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Wang Ming, and conducted a purge of the student body. The Comintern in China sent new student-revolutionaries to Moscow, but they were a dispirited bunch. Their schooling in the 1930s included a new emphasis on conspiracy and secrecy and lessons on withstanding interrogation. This training may not have been much use to students whose next encounter with political police was likely with the NKVD in the Great Purges a few years later.

Advertisement

One school for Manchurian operatives in Moscow was so secret that it was never officially acknowledged by the Soviet Communist Party, but its students continued the tradition of pairing off and having babies. Kang Sheng, who would become notorious as a brutal chief of the secret police under Mao, arrived from China to lecture at the University of the Toilers of the East (the main destination for Chinese students in Moscow after the demise of Sun Yat-sen University in 1930). He was trained for his harsh police work by the NKVD. Unlike some other Western commentators, who concentrate primarily on the exposure of Chinese students to the Soviet apparatus of political repression, McGuire emphasizes other ways in which they learned to think and live like Soviets. But repression was certainly an aspect of Soviet life that could not have escaped their attention. While they were not particularly targeted in the Great Purges, it is estimated that at least 1,700 Chinese citizens (not counting Soviet citizens who were ethnic Chinese) had been sent to the Gulag by 1939, and Chinese “enemies of the people” were executed as well.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the civil war in China between nationalists and Communists temporarily subsided as the two sides united against the Japanese occupiers. It resumed after the Japanese were defeated, but contrary to Stalin’s expectations, the Communists started winning and in 1949 took power as leaders of the new People’s Republic of China. The last two sections of McGuire’s book are devoted to the Sino-Soviet rapprochement of the 1950s, which lasted until their dramatic split at the end of the decade. This complicates, and to some extent risks undermining, her argument that the Sino-Soviet romance came to an end in the 1930s.

In the 1950s, although more than 20,000 experts were sent from the Soviet Union to help China modernize its economy, and over 8,000 Chinese students journeyed the other way to study science and engineering, the affective aspect of the relationship had changed. Earlier, McGuire argues, it had been a love affair, with the Chinese usually in the role of lover and the Soviets, only intermittently attentive, allowing themselves to be loved. Now the relationship was more often officially characterized in terms of friendship and brotherhood, yet the Soviets treated the Chinese with condescension, and the Chinese reacted warily. Perhaps remembering their own wild Soviet youth, the Chinese party leaders enforced a puritanical sexual code on students who went to study in the Soviet Union. The students themselves were dismayed that their Soviet classmates lacked interest in political instruction and engaged in such frivolous activities as drinking, gambling, and listening to jazz.

There was excitement in the air at Moscow University and other Soviet higher educational institutions, according to Soviet memoirs, sparked by renewed wartime contact with the West. But the general sense of release and intellectual possibility after the war would have made no sense to the young Chinese, if they even noticed it. To the exchange students, 1950s Moscow just looked “bourgeois,” even potentially “revisionist.” As one Russian pointed out to a Chinese colleague, the Soviet Union—which had once been as intense and single-mindedly focused on revolution as China—was just in a different phase of the development process; one day this would happen to the Chinese too.

Most historians of the Sino-Soviet relationship concentrate on the political leaders of the two states—the tensions surrounding the Soviet leadership’s reforms after Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin’s crimes in 1956, and Mao’s anger at Soviet “revisionism” and the resulting Sino-Soviet rupture that became visible to the world in 1960. But McGuire’s emphasis here, as in the rest of the book, is on the personal dimension. Her Sino-Soviet couples, products of the earlier “romance,” had a hard time as antagonism between Mao and Khrushchev built up in the second half of the 1950s, and a still harder time during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s.

Perhaps the most curious story is that of Li Lisan, a childhood friend of Mao’s from Hunan, who developed a political strategy known as the Li Lisan Line, promoting urban revolutionary uprisings in place of Mao’s rural strategy.* When Mao prevailed in the struggle and Li was held responsible for a botched military campaign in the south, he was sent in disgrace to Moscow in 1930. His chief persecutor there was Kang Sheng, who became a member of the Politburo. In 1936 Li married a Russian woman named Liza Kishkina, and they settled into a single room at the Lux Hotel. Li was arrested during the Great Purges, but Liza stood by him. He was released and allowed to return to work in 1939, before being recalled to China in 1945.

Back in China, he rather surprisingly fought for and won permission for Liza and their daughter to join him (it was more common for returned Chinese to jettison old Russian relationships quietly and establish new Chinese families). A second daughter was born soon after. The result was a household of four that, despite its Chinese patriarch, adopted the language and cultural traditions of its three female members, Liza and her daughters (joined in due course by Liza’s mother and a Russian nanny). Li ended up a casualty of the Cultural Revolution, persecuted once more by Kang Sheng, and probably tortured to death by Red Guards. Liza spent eight years in prison.

Mao is often pictured as a leader who, unlike his Moscow-trained rivals, kept his distance from the Soviet Union and, with the Long March, created an indigenous “origins” story for his party that took the spotlight off Moscow. McGuire, like the recent Russian biographer Alexander Pantsov, complicates this picture by showing his many and complex personal and political connections with the Soviet Union. Mao only visited once, for a rather humiliating three-month stay in 1949, cooling his heels at Stalin’s pleasure despite the fact that his Communist forces had just defeated Chiang’s KMT in China’s civil war. But two of his sons were sent to the Soviet Union for safekeeping in 1936, and his third wife left him in his cave in Yan’an in 1938 to go study in Moscow. She then worked for a while in the orphanage in provincial Russia where her daughter by Mao was enrolled, and ended up in a Soviet mental hospital.

McGuire also makes note of the fact that Mao allowed some “Muscovites” to remain in top leadership positions after the creation of the People’s Republic of China. But her main concern is emotional experience, not political influence. Even prominent Chinese Communist leaders who, like Wang Ming and Deng Xiaoping, studied in Moscow receive scant attention if they left no evidence of participating emotionally in the Sino-Soviet romance. It is tantalizing to learn, in a passing mention of Deng’s days as a student in Moscow, that his Soviet teachers rated his leadership skills higher than those of his fellow student Jiang Jingguo—Chiang Kai-shek’s son—although each was deemed a “good political worker.” Half a century later, Deng exercised those skills as leader of the People’s Republic of China while Jiang led the nationalist regime in Taiwan.

McGuire is a natural storyteller, so it is the quirks of individual fates rather than any overarching generalizations that are likely to linger in readers’ minds: for example, the Russian-speaking Chinese “orphans” being brought back to China by the party’s Central Committee after the Communist victory and hating it, especially the food; or Li Lisan’s Russian widow, Liza, having to care for her three-quarters-Chinese toddler grandson after her years in solitary confinement. The oddest of these fates is that of the Belarusian working-class girl Faina Vakhreva, who in the early 1930s met a boy called “Chinese Kolia”—Jiang Jingguo—at a machine-building plant in the Urals. Jiang had been studying in the Soviet Union in 1927 when his father crushed the Communists in Shanghai; he criticized his father in public and stayed in Moscow, voluntarily or involuntarily, for the next twelve years. Faina married him and ultimately became a decorous but publicity-shy first lady in Taiwan. She left no account of her life, although a few photographs survive, including one of her in a rather sexy but uncomfortable pose in a swimsuit on a pebbly beach in Yalta during her honeymoon.

Jiang, by contrast, left not one but two autobiographies, from diametrically opposed political perspectives. One portrays his Soviet experiences positively, in the style of a classic Soviet memoir, the other negatively, in the style of a classic anti-Communist one. Unfortunately, McGuire tells us almost nothing about the provenance of these two memoirs, or even the sequence in which they were written, but from her bibliography it appears that the pro-Soviet one was published in Shanghai in 1947 while the anti-Soviet one appeared as an appendix in a 1989 volume edited by the CIA analyst Ray Cline.

Was the real Jiang a Soviet hostage and (anti-Communist) Chinese patriot who had no reported private life and performed hard labor, while only waiting for the day he could return to his native land? Or was he the ardent young Communist who was proud of his success as a collectivizer, later went to the Urals to propagandize Soviet industrial achievement, and there started a Soviet family? McGuire is inclined to favor the second version, but her point is that there was more than one Jiang—just as there was more than one homeland in the hearts of those young Chinese revolutionaries who fell in love in and with the Soviet Union, and the children who were the product of their Sino-Soviet romance.

This Issue

April 19, 2018

A Mighty Wind

The Question of Hamlet

More Equal Than Others

-

*

Li’s story may be familiar to some readers from Patrick Lescot’s biography, published in English as Before Mao: The Untold Story of Li Lisan and the Creation of Communist China, translated from the French by Steven Rendall (Ecco, 2004). ↩