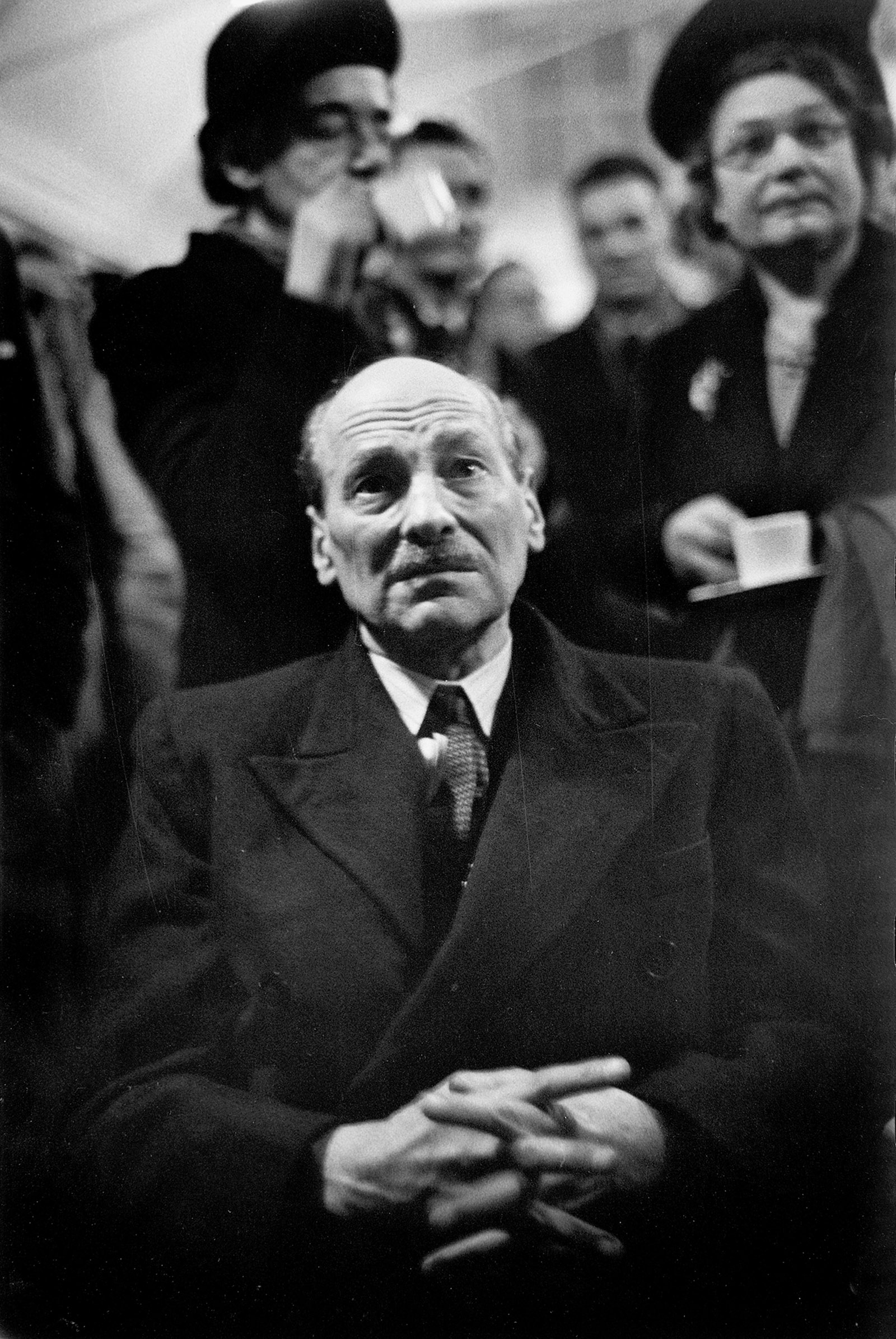

Was any public figure ever so conspicuous for being inconspicuous? “An empty taxi drove up to Number 10 and Mr. Attlee got out.” I think this was the first political joke I ever laughed at; I must have been nine or ten at the time. It was attributed to Winston Churchill, but it dates back to the nineteenth century when it was applied to Sarah Bernhardt, though for her thinness, not her dimness. “Mr. Attlee is a modest little man with plenty to be modest about.” Churchill did say something along these lines, though in one form or another that too is an ancient insult. A “sheep in sheep’s clothing” was also attributed to Churchill, though in fact it was Malcolm Muggeridge who said it.

Nor were Clement Attlee’s Labour Party colleagues any more complimentary. Hugh Dalton, who was briefly to be his chancellor of the exchequer, recorded in his diary when Attlee became party leader, “And a little mouse shall lead them!”; on other occasions he referred to him as “poor little Rabbit.” There was something about Clem that inspired comparisons from the animal kingdom. As he announced victory in North Africa in 1943, one of the turning points in World War II, Harold Nicolson thought he was “like a little snipe pecking at a wooden cage.” In 1945, after he had been deputy prime minister for three years and was about to become prime minister for the next six, he was lampooned in the leftist weekly Tribune as “The Invisible Man”:

There is no doubt whatever that Attlee exists

(Once head of HM Opposition)

But in Government circles the rumour persists

That Attlee’s a mere apparition.

Only the deeply loyal Ernest Bevin, the trade union leader who became Britain’s most memorable postwar foreign secretary, really respected him. The rest of the vain and envious crew—Hugh Dalton, Herbert Morrison, Stafford Cripps, Aneurin Bevan—never thought he was up to the job of leading them, which he did for twenty years, surviving four direct challenges with barely a twitch of his little mouse’s whiskers.

In some of these dismissals there was a barely concealed snobbery. Bevan deplored Attlee’s “suburban middle class values.” Isaiah Berlin did not care for his “minor public school morality.” Beatrice Webb said that “he looked and spoke like an insignificant elderly clerk.” Attlee himself shrugged off these putdowns. He was not in the least ashamed of where he came from or who he was. “I am a very diffident man,” he gladly conceded. “I find it very hard to carry on conversation.” When journalists like Nicolson implored him to build up his public image, he demurred, insisting on his privacy. In any case, “I should be a sad subject for any publicity expert.”

He could make Calvin Coolidge look like a chatterbox. At the Labour Party conference in Margate in 1953, he ate breakfast, lunch, and dinner alone every day. In interviews, he was famously laconic. He once answered twenty-eight questions in five minutes. When a distraught minister asked him why he was being sacked, Attlee replied curtly: “Not up to it.” When Morrison wrote him a weasely letter announcing his intention to run against him for the party leadership in 1945, Attlee replied, “Thank you for your letter, the contents of which have been noted.”

Yet he was not without a sly self-regard. In old age, he could not resist sending a limerick to his beloved older brother Tom:

Few thought he was even a starter

There were those who thought themselves smarter

But he ended PM

CH and OM

An earl and a knight of the garter.

Today the nonstarter is regarded by many as the greatest of all twentieth-century British prime ministers. That was the verdict in 2004 of a survey of British academics, the modern equivalents of E.P. Thompson, Raymond Williams, and Ralph Miliband, who had at the time condemned the Attlee governments as timid and unadventurous. To jaded modern eyes, the Attlee style looks more and more attractive, with its total absence of spin or flashiness, its freedom from sleaze and dodgy hangers-on, its unadorned plainness and modesty. What a contrast between today’s pretentious cavalcades and Violet Attlee in her battered old Hillman driving her husband to kiss hands at Buckingham Palace. Better still that Violet was notorious as the worst driver in the Home Counties.

Nor is this new admiration simply a matter of style. The subtitle of John Bew’s superb biography is no gimmicky overstatement. We are increasingly aware that, in a deep sense, it really was the Attlee government and Attlee himself who “made modern Britain.” Theresa May, in her first speech as prime minister to the Conservative Party conference, in 2016, included Attlee among her heroes, alongside the conventional Tory icons of Disraeli, Churchill, and Thatcher. The partial undoing of the Attlee legacy by Thatcher and her successors has not much altered the nation’s underlying mindset, as the annual survey British Social Attitudes has repeatedly shown. The title of the thirty-fourth report, for 2017, pretty much sums up the continuing ethos: “A kind-hearted but not soft-hearted country.”

Advertisement

Clem was all the things his critics said he was. He had a tinny voice and a slight figure, though as you can see from photographs of the war cabinet he was in fact slightly taller than Churchill, 5 foot 9 inches as against 5 foot 6 or 7, but whippet-thin as opposed to the overfed bulldog beside him. He was indeed born in the London suburbs, though very much at the prosperous end. His nanny had once been Churchill’s nanny, and his father, Henry, was a lawyer rich enough to buy a country house in Essex. The Attlees were both affectionate and high-minded, and most of them devoted their lives to serving the community.

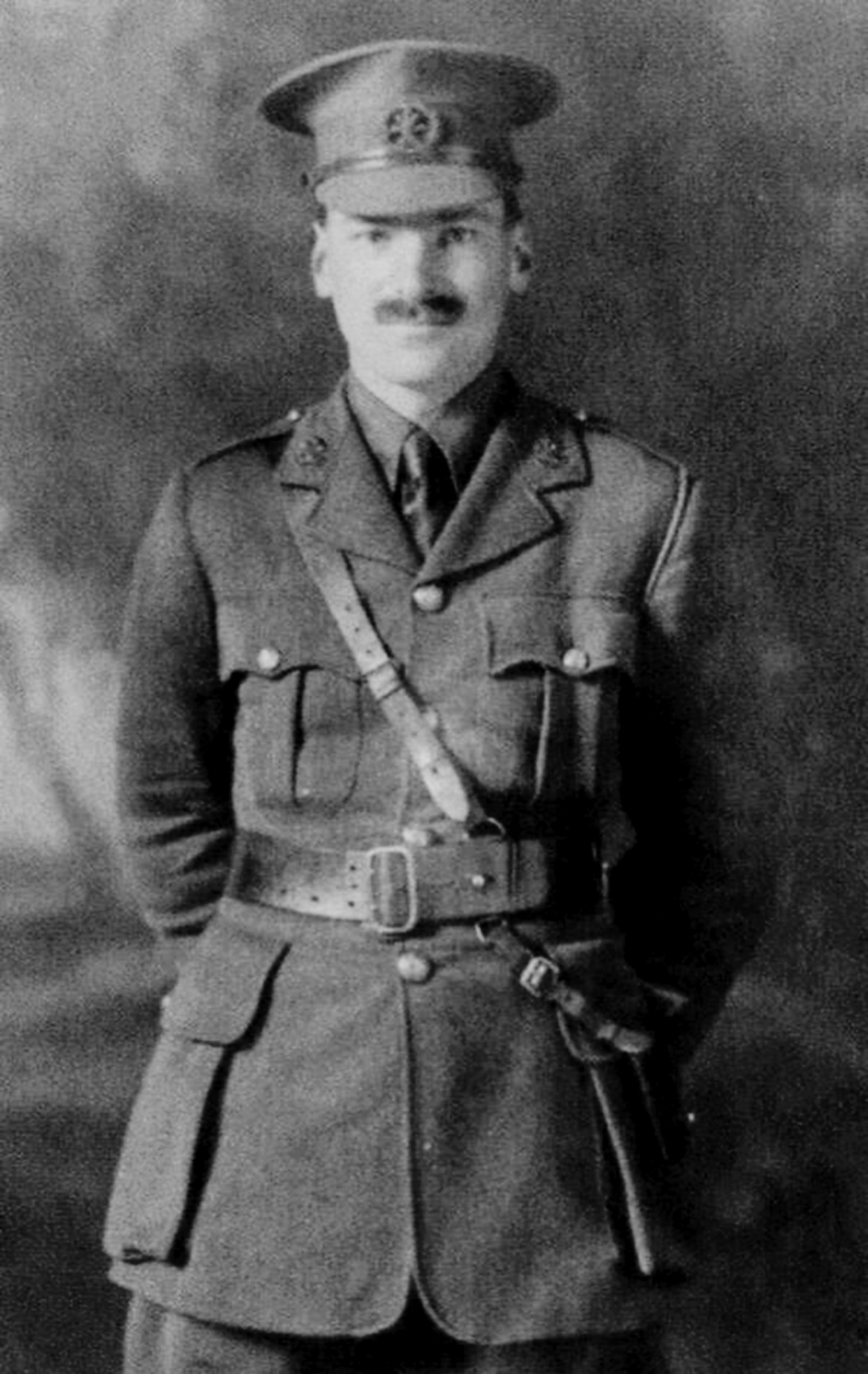

Henry Attlee was disgusted by the degeneration of the British Empire into a scramble for gold and diamonds, but that did not deter him from sending Clem, his seventh child and fourth son, to Haileybury College, the nursery for the Indian Civil Service. Clem conceived a lasting loyalty and affection for every institution he joined, but Haileybury was his first and last love. After leaving Oxford, he went straight to the Haileybury Club in Stepney, one of the roughest parts of London’s East End, and took up residence there. Every self-respecting Victorian public school had set up its own club in the slums. The well-heeled alumni would leave their City stools and go to play ping-pong and soccer with the underprivileged lads. Clem specialized in subjecting his cohort to military drills, becoming in the process a lieutenant in the Territorial Army. He devoted himself to the club right up to 1914. When the lads joined up, so did he.

No one could be more aware from firsthand experience of the intensity of working-class patriotism and of the unreality of the Marxist fantasy that the workers of the world would unite to prevent a global war among the imperialists: “Race, language, colour, religion and history are stubborn things that do not disappear with the waving of a Marxian wand,” he wrote thirty years later. No one could feel more passionately about his country than Clem: “I love England and especially dear, ugly East London, more than I can say.” Among twentieth-century prime ministers, only Stanley Baldwin was moved to such eloquence by his native landscape, but Attlee’s was less of an homage to an imagined rural past: his fatherland was not only

the true England of Nature, the trees, hedges, grass and the lie of the land, but even the transitory England of the C20th with its railways, towns and lighted streets, above all, the lit pavements shimmering and wet with rain.

Attlee poured his most intense feelings into the poetry he read and wrote. Bew reanimates those feelings by heading his chapters with snatches from Attlee’s favorite lines, from Kipling’s “Recessional” to The Hunting of the Snark, stanzas of which he and Churchill quoted to each other, identifying their fellow politicians as the Beaver or the Barrister. By contrast, Attlee was implacably hostile to the “mumbo-jumbo” of organized religion. In particular, he ridiculed “the clerical fatuity” of the Church of England, seen at its posturing worst among the chaplains of the Great War. His favorite poets were all anticlerical if not actively atheistic: Blake, Keats, Shelley, Swinburne, Hardy (though he preferred the Wessex novels). In later life, he lapped up Gibbon, reading at Chequers the set of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire that Churchill had left behind. He also relished the stimulating essays of Cecil Delisle Burns, a Catholic seminarian who had defected to become the resident guru of the South Place Ethical Society.

A captain in the 6th South Lancashire Regiment in 1915, Attlee crouched for three weeks under Turkish bombardment on that narrow strip of sand at Gallipoli. It was there that he wrote “Stand To”:

From step and dug-out huddled figures creep

Yawning from dreams of England; bayonets gleam…

And rat-tat-tat, machine guns usher in

Another day of heat, and dust, and flies.

Not quite Owen or Sassoon, but not entirely negligible either.

As an infantry officer, Attlee quickly developed some of those qualities for which he later became famous in politics: unswerving diligence and devotion to duty, brisk attention to the task, and a sharp impatience. As the snow began to fall and frostbitten bodies were carried down from the trenches on the higher ground, Captain Attlee immediately recognized the danger to his company:

Advertisement

To warm up his men, who stood shivering, he ordered them to run on the spot, and permitted them to make use of their rations of rum. He set them to digging new dug-outs, issued fuel and petrol and got some fires going in old tins they had picked up on the beach. He then ordered a foot inspection and made all the men with sodden feet rub them with snow to make sure that the blood was circulating.

When it came to the inevitable evacuation, he and Lieutenant General Frederick Maude were the last men off the beaches in what had been the only efficiently managed part of the whole disastrous expedition. Attlee continued to think that if it had been properly led and supported, the Gallipoli campaign would have succeeded. Since fewer and fewer people continued to think this, his conviction led to a lasting bond with Churchill, who as First Lord of the Admiralty had inspired and pushed it through from first to last.

A few months later Attlee was in the fierce fight at Kut al-Amara in Mesopotamia, where he led his men over the top carrying the red flag of the South Lancashires and was wounded in the buttock by friendly fire. He wrote to his brother Tom, who was facing imprisonment as a diehard conscientious objector, “it might be interesting to the comrades to know I was hit while carrying the red flag to victory.” Tom was eventually sentenced to solitary confinement and was in Wandsworth Jail while Clem was recuperating from his wounds in nearby Wandsworth Hospital. Their mother Ellen remarked, “I don’t know which of these two sons I am more proud of.” “Suburban” seems a rather inadequate epithet to describe the Attlees.

By the time he was elected to Parliament for Limehouse in 1922 (the first Oxford graduate to become a Labour MP), Attlee’s views and character were fully formed. In fact, they had been largely formed by 1914. He wrote to Tom, “I do not find my outlook very much changed during the war though I think I have attained slightly more catholicity.”

Bew rightly draws attention to the delicate precision of that last word. Attlee’s kind of socialism grew out of an ideal of shared citizenship, of engaging everyone in the pursuit of the common good. He acknowledged what liberalism had contributed, but the liberal ideal had had its day. The time had come for a universal state that would include all classes of society and protect their “welfare,” in every sense of that fine old Anglo-Saxon word. He had started thinking along these lines after reading William Morris, in particular his novel News from Nowhere (1897). But he came to find Morris’s rural craftsman’s paradise unrealistic and a trifle oppressive, and he turned back to a slightly earlier utopia, that in Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1887), which embraced urban life and welcomed mechanization as a liberation from backbreaking toil.

There was another vision that Attlee warmed to following World War I: Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Democracy, self-determination, open agreements, free trade, the League of Nations—all were woven into Attlee’s tapestry. He became a lifelong admirer of the politics and people of the United States, without a shred of the anti-Americanism that later infected the left. Hence he was an eager cold war partner in the Western alliance and the forging of NATO. The American distaste for socialism never weakened that loyalty. And loyalty was the first quality that endeared Attlee to all sorts of people: East End dockers, Durham coal miners, trade union MPs (if not middle-class intellectual socialists like Harold Laski), and American statesmen from Truman on down—all of them felt that you could rely on Clem.

He was no less steadfast in his own brand of socialism, which was wholehearted and uncomplicated. He didn’t much care for Sidney Webb. Looking back on the Labour movement before 1914, he reflected, “We were too Webby—I’m sure I was, having a fatal love of statistics and a neat structure of society.” But he gave enduring allegiance to the 1918 constitution that Webb drafted, including its celebrated Clause IV (actually IV.4):

To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible, upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.

Twenty years later, in The Labour Party in Perspective (1937), Attlee quoted the 1918 party goals, insisting that they were “approximately as they stand to-day” (and indeed went on standing until 1995, when Tony Blair managed with great difficulty to persuade the party to dilute them). And Attlee meant it.

Within three years of his becoming prime minister, “the commanding heights of the economy” (a phrase first used by Lenin) were all in state hands: coal, gas, electricity, railways, trucking, and the Bank of England, with iron and steel to follow. All of these have now been returned to the private sector, mostly under Thatcher and mostly with measurable benefits to the customer (notably in water and telecommunications, which were state-owned before Attlee). As for coal, once the king of British industry but now almost wiped out, it is hard to say exactly what would have happened without the Tory counterrevolution. Pits were already being closed by the dozen under the National Coal Board. The best guess is that the rundown would have been slower had the industry remained in public ownership.

The legacy of the Attlee years that remains is the fourfold system of welfare put in place in a single year, 1948: the national health service, national insurance for pensions and sick pay, the national industrial injuries scheme, and the national assistance for the very poor. These remain at the core of the British social system and, though much tweaked, chiseled, reformed, and reencrusted by succeeding governments, have never been fundamentally challenged. Danny Boyle’s dazzling masque at the opening of the London Olympics in 2012, with its columns of marching nurses, reflected the continuing centrality of the NHS in the nation’s affections. It was an Attlee tribute show.

It is possible to see all this as the outcome of a patriotic consensus forged during World War II. After all, the basics were put in place by Tory ministers in the wartime coalition such as Sir Henry Willink (health) and R.A. Butler (education), and by Liberals such as Sir William Beveridge (social insurance) and John Maynard Keynes (macroeconomics). It is true too that all through the 1930s the tendency was for institutional consolidation at the national level, such as the British airways corporations and the BBC. There is plenty of Attlee-type thinking to be found in Harold Macmillan’s The Middle Way (1938).

But these valid qualifications must yield primacy to the efforts of Attlee himself, as Churchill’s deputy in the coalition, to prepare the way for the sort of postwar settlement that to his chagrin had not followed World War I. He often slid the essential elements into place while the old man’s back was turned, though not against his will, for Churchill retained enough of his Liberal leanings to be in sympathy with the general direction. The one animal to which I have not seen Attlee compared is the mole, the analogy so beloved of Karl Marx. In Britain at least, the sternest anti-Marxist on the left burrowed longer and deeper than his opponents. When The Labour Party in Perspective was reissued in 1949, the correspondent for The Washington Post wisecracked that not even Mein Kampf had given a more accurate indication of the author’s ultimate intentions.

From first to last, though, Attlee was insistent that he remained a democrat and a pluralist: “I am also in favour of variety and entirely opposed to the abolition of old traditions and the levelling down of everything to dull uniformity.” From his early days in the East End he was unflaggingly hostile to Marxism in theory and communism in practice, having becoming familiar with the brutal and devious tactics of Communists in the trade unions. In 1950, toward the end of his premiership, it was he, and not as popularly thought Margaret Thatcher, who first warned the public to beware of “the enemy within,” that is, Communist infiltration into the trade unions.

He was as hard as any of his opponents on the left, not only in his adamant adherence to his own principles but also in his ruthlessness, which he never hesitated to deploy in both war and peace. In the Cabinet’s discussion on May 15, 1940, he was one of the strongest proponents of an aggressive bombing strategy against Germany, even if it led to large-scale civilian casualties—as it did that very evening when the RAF launched a hundred bombers on the first mega-raid against the Ruhr, the cities of which were to be 80 percent devastated by the end of the war. He willingly took ministerial responsibility for stockpiling tons of poison gas, to be released in the event of an invasion of Britain. In later years, he made it plain that he would have had no hesitation in using it.

At the end of the war, Attlee took a strong line in favor of dismembering the German state, even if he stopped short of Henry Morgenthau’s plan for “pastoralizing” the country. He wholeheartedly supported Truman on the dropping of the atomic bomb and instantly concluded that Britain must have atomic weapons of its own and be prepared to use them. Fearful that his Labour colleagues might not support him, he set up a secret Cabinet committee, GEN 163, to authorize work to begin before any objections could be raised. The committee met only once, on January 8, 1947, and its decisions were not communicated to the Cabinet, then or later. Similarly, neither Cabinet nor Parliament got to hear of Attlee’s agreement with James Forrestal, the US secretary of defense, to station three groups of large bombers on British soil. When the Korean conflict loomed, it was a foregone conclusion that Attlee’s Britain would join in, even though the cost of rearming was to be a major factor in Labour’s downfall in 1951.

In his hardness, he was equaled only by Churchill himself. Yet to this day, the mouse remains in the lion’s shadow. Even the jacket blurb for Bew’s book spends several sentences talking about Churchill, before going on to argue that in fact Attlee may have been the more consequential leader. We can go further, I think. Without Attlee, Churchill might never have become prime minister at all, and might be remembered today only as a mercurial figure responsible for a series of catastrophic misjudgments: Gallipoli, the return to the gold standard, resistance to Indian independence, and, perhaps most pregnant of all, bombing the hell out of Mesopotamia in the early 1920s, the consequences of which haunt us still.

As long as the pacifist George Lansbury led the Labour Party, Attlee loyally supported its stance against rearmament. But after Attlee succeeded him in 1935—a succession by no means as unlikely as posterity has chosen to think—Labour began to become a staunch anti-appeasement and pro-rearmament party. In this process, Attlee immediately offered his undeviating support for the Spanish Republic and did not hesitate to visit the battlefront, where he gave the clenched-fist salute to the Major Attlee Company of the International Brigade. This gesture afforded Senator Joseph McCarthy a few more column inches, but hardly anyone ever dreamed of Attlee as a fellow traveler.

By 1938 Churchill and Attlee were in clandestine cahoots. For Attlee, the Munich Agreement was “one of the greatest diplomatic defeats that this country and France have ever sustained.” So began the tense process by which Attlee became the kingmaker. True, Churchill might eventually have emerged on top of the heap of agonized Tory ministers, but the support of Labour made his replacing Neville Chamberlain a quick and decisive business. Churchill never forgot it.

Oddly enough, it is in covering the Attlee government that Bew’s book loses some of its earlier vivacity and intensity. There is a certain blandness about his account of the domestic scene in the late 1940s. He does not bring alive as David Kynaston does in Austerity Britain (2007) the grimmer aspects of the Attlee years, the physical and moral exhaustion, the lines, the rationing, the bureaucracy, the fuel shortages, and not least the drastic devaluation of the pound in 1949, which was experienced as a national humiliation, though in reality it was a lifeline. Bew mentions only in passing those like Correlli Barnett in The Audit of War (1987) and The Lost Victory: British Dreams, British Realities 1945–1950 (1995) who argue that Britain frittered away its scanty resources on welfare rather than rebuilding with the same urgency as France and Germany.

Nor does Bew discuss a slightly different argument: that a government that loosened up the economy more boldly, as Harold Wilson began to do in late 1948 with his “bonfire of controls,” and relied more on the free market and less on government direction and control might have revived the animal spirits not only of entrepreneurs but of the general public. Labour did win the largest popular vote ever in 1950 and 1951 (though the Conservatives nonetheless came out of the 1951 election with a parliamentary majority, and Attlee resigned as prime minister), but might it not have done better still if it had responded to the public desire for economic elbow room?

Like Attlee, Bew seems reluctant to enter too closely into economic controversy and evaluation. In fact, Attlee was singularly uninterested in commerce at any time in his life, still less in consumption. If half a glass of sherry was good enough for himself and his guests, why should anyone else want more? For Attlee, austerity was not simply the necessity of the times, it was his own instinctive preference. Which is perhaps why posterity has chosen to retain fonder memories of Churchill, with his cigars and his brandy and his racehorses.

This Issue

April 19, 2018

A Mighty Wind

The Question of Hamlet

More Equal Than Others