Early in the fourth story of The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, we are introduced to a shadowy character named Darcy Miller, a writer dying of liver cancer in the middle of nowhere. The narrator tells us that this writer, his friend, once published under the name “D. Hale Miller.” He goes on to say that “I’m aware it’s the convention in these semi-autobiographical tales—these pseudo-fictional memoirs—to disguise people’s names, but I haven’t done that.”

Even granted the latitude of fiction, this statement is simply untrue. There has never been an author named D. Hale Miller, but there certainly was Denis Hale Johnson, who died at the age of sixty-seven in May 2017, also of liver cancer, and on those occasions when I encountered him, he “looked,” as the narrator says of D. Hale Miller, “something like a child snatched from a nap.” The story in which D. Hale Miller appears is titled “Triumph over the Grave,” and like the other stories in this collection, it has the black crepe of mortality hanging directly over it. The Largesse of the Sea Maiden contains another, more alarming feature: affrighted intuitions about the afterlife, combined with the trappings of religious and gothic fiction, including doppelgängers, grave robbers, ghouls, and demons. In fact, it doesn’t feel like a last book so much as a thoroughly posthumous one. “It’s plain,” the author writes, “to you that at the time I write this, I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.” All right, then: Where is the triumph over the grave to which the title of the story refers? And what is it?

Denis Johnson’s first two books were collections of poetry, and he published poems intermittently throughout his career. The narrator in one of the stories in The Largesse of the Sea Maiden says that his own poems were “fraudulent,” but Johnson’s early poems nevertheless point to some of the directions his work would take him. A reader who might have chanced upon Inner Weather, for example, published by Graywolf Press in 1976 in an edition of six hundred copies (and not listed among the author’s works in the later novels), might be startled by the tone of calm anguish that most of the poems project. They suggest a long-standing acquaintance with desolation. Here is the final stanza of the book’s first poem, “An Evening with the Evening”:

Suddenly it is the total blackness

with the numerous small lights of the face

of the city shining through it;

then it is the end,

which is only himself, going

home to his wife and children,

turning and trying to walk away from the darkness

that precedes him, darkness of which he is the center.

The darkness, this stanza asserts, is internal and thus unavoidable. Just about all the poems in the book sound like that: the speaker lives in a world populated (vaguely) by family members or friends, but his primary experiences, the ones he insists upon, are solitary and nocturnal. Other people are simply shadows on the wall, and he himself is a carrier of obscurity, holding a flashlight that beams darkness into every corner at which he points it. This despairing stoicism goes beyond late-adolescent or young-adult estrangement and seems to claim itself as a permanent condition, an identity. The poems relentlessly refuse, however, to explain where this condition came from.

Reading Inner Weather when it first came out, I thought of Coleridge’s “Dejection: An Ode”:

A grief without a pang, void, dark, and drear,

A stifled, drowsy, unimpassioned grief,

Which finds no natural outlet, no relief,

In word, or sigh, or tear—

The comparison to Coleridge, whose poems desperately try to cheer themselves up and to free themselves from the gloom that is their natural habitat, also brings to mind a condition in which drugs or despair, or some combination of the two, have somehow blown several fuses in the speaker’s psyche, damaging him permanently. One is stuck in the lime tree bower when all the friends have gone elsewhere; the wind has died, and the ship drifts in the middle of the sun-struck ocean; demons somehow cross the threshold and enter the house. When happy endings are tacked on to such narratives, they sound implausible, fraudulent. For Coleridge, these situations are terrifying. By contrast, in Denis Johnson’s fiction they often become an occasion for comedy.

Like the books of Graham Greene, a writer whom Johnson admired and quoted in the epigraph for his first novel, Angels (1983), and who also had an interest in hellish landscapes, Johnson’s longer narratives seemed to have been written in two different genres for two different audiences: fun-filled “entertainments” powered by violent action and suspenseful plots for the light-minded reader and, by contrast, “novels” weighed down with spiritual matters for everyone else. The more serious books, such as Tree of Smoke (2007), which won the National Book Award, or The Stars at Noon (1986), are tales with exotic locations in which the main characters undergo various kinds of spiritual and political trials. Johnson, like Greene, had a particular interest in broken-down romantic outlaws and characters who imagined themselves damned or exiled from humanity. Recluses turn up with some frequency in his work, showcasing a subject (isolation) and sensibility (stoicism) that can also be traced back to Joseph Conrad.

Advertisement

Johnson’s noirish pulp narratives, including Nobody Move (2009) and, more recently, The Laughing Monsters (2014), are thrillers whose far-flung main characters leave slime trails all over the globe. The point is, however, that the monsters are now laughing, which makes them lively company, though not less dangerous than before. Finishing a Denis Johnson novel, the reader is likely to remember the mood, the purity of feeling, and the brilliant sentences more clearly than the plots, which are often quite secondary and occasionally contrived.

Despite his gifts as a poet and a novelist, Johnson is probably best known for his book of stories, Jesus’ Son (1992), whose reputation overshadows all his other work and which is an earlier companion volume to The Largesse of the Sea Maiden. What seemed new in Jesus’ Son was an amalgamation of several seemingly disparate elements that the longer novels had to explain away or smooth out. These elements include characters who are working-class down-and-outers; a series of apparently disconnected narrative fragments experienced by the drug-addled and violence-prone cast, one of whom, known only as “Fuckhead,” takes center stage; and a transformation of the drug experience into a spiritual pilgrim’s progress. Jesus is right there in the title, just as angels are in the title of Johnson’s first novel. Readers can’t say they haven’t been warned. “And the Savior did come, but we had to wait a long time.”

This title, however, and its particular Jesus constitute a tricky spiritual proposition: the phrase “Jesus’ son” is a quotation from a Lou Reed song, “Heroin,” that conflates the drug experience with religious exultation: “When I’m rushing on my run/And I feel just like Jesus’ son.” Drugs and God and the god-feeling are never clearly separated in these stories until the very end, when the narrator, turning over what amounts to a new leaf, announces that he is “just learning to live sober.”

The central preoccupation of Jesus’ Son has to do with Fuckhead’s inability to help out anybody, including the people he cares about. The pain of others can be terrifically entertaining when you’re high, as the first story, “Car Crash While Hitchhiking,” demonstrates. Remembering the victims of an auto accident, the protagonist shrugs them off: “And you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you.”

In his indifference to suffering, or, worse, his attraction to the spectacle it presents, Fuckhead, our narrator, is a dangerous puzzle to everybody else and to himself, particularly when he’s the life of the party. The stories cumulatively try to account for his behavior, and they seem to be searching for the mysterious sources of empathy available to normal people. Much of the book reads as if a lost soul is trying to find the formula for repairing his missing heart and spirit. The book’s path takes this pilgrim toward a redemption of sorts in an assisted-care facility called the Beverly Home, where Fuckhead finds gainful employment once he has sobered up and where he learns, quite literally, how to touch people:

All these weirdos, and me getting a little better every day right in the midst of them. I had never known, never even imagined for a heartbeat, that there might be a place for people like us.

Before that, however, we are treated to a series of vignettes and episodes of bad behavior, narrated with the disconcerting offhandedness of someone in a bar telling you a good yarn about the evil misadventures he has somehow survived. The reader is often implicated: after all, who doesn’t enjoy reading about catastrophes that have befallen someone else? The narrator always seems to be conscious of his audience and of its relative complicity or resistance to stories of personal disaster, and he regularly turns his gaze toward us to ask a question or to answer a question that he believes we have posed, as in “Beverly Home”:

How could I do it, how could a person go that low? And I understand your question, to which I reply, Are you kidding? That’s nothing. I’d been much lower than that. And I expected to see myself do worse.

Or in “Dundun”:

Will you believe me when I tell you there was kindness in his heart? His left hand didn’t know what his right hand was doing. It was only that certain important connections had been burned through. If I opened up your head and ran a hot soldering iron around in your brain, I might turn you into someone like that.

Donald Dundun, whose “left hand didn’t know what his right hand was doing,” shows up again in The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, providing a connection from the earlier stories to the more recent ones. In the new book, Dundun and the narrator befriend each other when they are both incarcerated in a county lockup. Later, once they are both released and out in the world, Dundun, who looks like “a nasty little Neanderthal,” hides out with the narrator after committing a robbery and a murder. Dundun gives the narrator so much heroin that he becomes “thoroughly addicted…. My fate was sabotaged.”

Advertisement

Many of the preoccupations of Jesus’ Son reappear in the new book, in which the stories again have an episodic nature. For the most part they do not build in a linear way but create a unified impression by pasting anecdotes and vignettes next to each other, most of which convey a single anxiety: the question of how a person should live, or, more particularly, given the whiff of the graveyard, how a person should have lived. The collection’s five stories typically deal with aftermaths—the consequences of actions already taken, actions that cannot be undone, “the difference,” one character notes, “between repentance and regret.” The book could have been titled The Varieties of Religious Experience and every story titled “The Sick Soul.” And once again, the narrator regularly turns toward his readers to address them as if they were fellow collaborators: “You and I know what goes on,” he observes.

Johnson’s brilliance lies in his ability to make desperate spiritual and psychic troubles entertaining before the tone reverses itself and drops headlong into darkness. The secret to this particular effect is to keep things moving and not to dwell on any particular moment for more than a few paragraphs. Even those with short attention spans may find themselves tumbling into one abyss or another set up as narrative booby traps. Besides, Hell is rarely boring. The effect on the reader is disconcerting: we are in the presence of a quick-witted and companionable tour guide who is taking us to infernal places where no one would willingly go.

The book’s eponymous story is narrated by an ad man, Bill Whitman, in ten titled sections. It proceeds through a set of associations and seemingly unrelated events: a woman kisses the scar tissue of a man’s severed leg; the drunken host of a dinner party takes his prized Marsden Hartley painting off the wall and burns it in the fireplace simply because he can; the narrator confesses his lies and infidelities to his dying first wife and then becomes confused about whether it’s really his first wife he’s speaking to; a painter commits suicide by jumping off the Nello Irwin Greer Memorial Bridge; and the narrator wanders around his neighborhood in his bathrobe and slippers, looking for instances of magic. His daily life has lost its savor, if it ever existed. An award for his advertising work makes him physically sick. His marriage limps forward: “Have I loved my wife? We’ve gotten along.” His children? “They aren’t beautiful or clever.” As a narrator, he resembles the speaker of the poem “An Evening with the Evening”: solitary, stoic, and desolate, someone who carries the darkness around with him.

Running through all the story’s episodes is a question that the narrator, in proper Johnsonesque fashion, poses to the reader: “I wonder if you’re like me, if you collect and squirrel away in your soul certain odd moments when the Mystery winks at you.” The painter, Tony Fido, seems particularly adept at finding those mysteries: “He believed in spells and whammies and such, in angels and mermaids, omens, sorcery, wind-borne voices, in messages and patterns.” The story’s climax, such as it is, occurs in “a dim tavern” off Union Square that the narrator has entered at one in the morning; the tavern has one other customer, a woman who sets off the quasi-epiphanic vision that follows:

I let the door close behind me. The bartender, a small old black man, raised his eyebrows, and I said, “Scotch rocks, Red Label.” Talking, I felt discourteous. The piano played in the gloom of the farthest corner. I recognized the melody as a Mexican traditional called “Maria Elena.” I couldn’t see the musician at all. In front of the piano a big tenor saxophone rested upright on a stand. With no one around to play it, it seemed like just another of the personalities here: the invisible pianist, the disenchanted old bartender, the big glamorous blond, the ship-wrecked, solitary saxophone… And the man who’d walked here through the snow… And as soon as the name of the song popped into my head I thought I heard a voice say, “Her name is Maria Elena.” The scene had a moonlit, black-and-white quality. Ten feet away at her table the blonde woman waited, her shoulders back, her face raised. She lifted one hand and beckoned me with her fingers. She was weeping. The lines of her tears sparkled on her cheeks. “I am a prisoner here,” she said. I took the chair across from her and watched her cry. I sat upright, one hand on the table’s surface and the other around my drink. I felt the ecstasy of a dancer, but I kept still.

Readers with long memories may recall a similar moment in Jesus’ Son, when the narrator observes a woman who has been informed that her husband has just died in an auto accident: “She shrieked as I imagined an eagle would shriek. It felt wonderful to be alive to hear it! I’ve gone looking for that feeling everywhere.” Readers may differ about how to understand this moment. Some see it as the narrator’s envy of the woman’s purity of feeling, its spiritual amplitude, with all the profound grief and mystery encoded into it. But there is a hint here also of the narrator’s standoffishness, his tendency to turn suffering into a spectacle that he’s more than happy to watch. If he has that tendency, and if he understands it as a flaw in himself (as I think he does), then he needs to engage in the self-repair that gives Jesus’ Son its arc and direction.

In the dim tavern off Union Square where that anonymous woman weeps and says that she’s a prisoner, Bill Whitman, the story’s narrator, with whom we are forced to identify since there is no other consciousness to which we have access, does not offer comfort—as if any kind of consolation were possible. Instead, he observes her suffering as he rises higher and higher to an ecstatic state, searching, it seems, for his own empathy. The Mystery has arrived, and he’s there to witness it. In this way, the misery of others becomes a magnificent spectacle that stops the show. No other contemporary writer has been more acute on the subject of our collective, vicarious ghoulishness, enflamed by TV and movies: Johnson seems to understand completely what drivers are doing when they apply the brakes to see roadside wreckage.

This narrator may be a Whitman, but not the one who offers his tender comfort to anyone who needs it. With his drink in hand, this Whitman sits there to observe you in your moment of anguish without feeling any need to intervene, yet this hands-off Whitman is as much a true-blue American as the nineteenth-century hands-on one.

The next three stories constitute the heart of The Largesse of the Sea Maiden. They seem to offer, in their various ways, a means of thinking and feeling that might serve as an antidote to the delicate, civilized recessiveness of Bill Whitman. What they offer—and there is no other way to say this—is faith: faith in God, in angels, love, and art. Nothing else works; everything else has been tried.

“The Starlight on Idaho” consists of a series of desperate letters written by a character named Mark Cassandra (the names in these stories are nearly always significant in one way or another). Like Saul Bellow’s Herzog, another character at the end of his rope, Johnson’s Cassandra is writing letters to everybody, but their tone lies a great distance from Herzog’s urbane wit; these letters sound the note of a soul that gradually realizes it is being squeezed by demonic forces. Sitting in a room and doing his best to stay sober at the Starlight Addiction Recovery Center, formerly the Starlight Motel, Cassandra begins by sending notes to old girlfriends, to his grandmother, and to Pope John Paul, to whom he confides: “There really is a Devil, he really does talk to me, and I think it might be coming from some Antabuse giving me side effects.”

From here on until the end of the story, as Cassandra finds himself writing to members of his own family and to Satan, the tone modulates to what might be called deadly earnestness. Cassandra sometimes thinks of himself as Jesus, but his delusions don’t feel entirely delusional, given the force of the vision behind them. The story at no point intimates that Cassandra’s beliefs in Satan or God are foolishly mistaken, or that they are capable of being deconstructed or demythologized. For this character held captive by his past misdeeds, Satan is a fact: “Devil laughing so close I saw the veins in his teeth.” Then Cassandra elaborates on his vision:

And the cave was his mouth like a bathroom full of stink and his tongue popped with cheap sweat. Yeah boy he dragged me down to his jamboree. Dragged me down through the toilet formerly known as my life. Down through this nest of talking spiders known as my head. Down through the bottom of my grave with my name spelled wrong on the stone. Standing on his stump shouting jive. Jest get a whiff of sulphur and wet fear! Come breathe these rank aromas for the purposes of course of scientific inquiry alone! The mayor is inside already! Come! It’s all respectable! Satan says The gamblers shake the dice, and I shake the gamblers, Snake eyes in Paradise!

Snake eyes, indeed: when you look evil in the face, the spectacle stops being funny, even though laughter is what got you there in the first place.

Johnson had an unsettling gift for laying out the details of Hell in passages like this one, where the feeling for damnation is not bookish but lived-through and authentic. “My life is the amazing truth,” Cassandra says, and although you can argue with a system of belief, you can’t really argue with a life. Cassandra finally signs off as “Your Brother In Christ.”

The following story, “Strangler Bob,” in which Dundun reappears, will remind some readers of the tales in Jesus’ Son. The narrator, Dink, says of people who show up repeatedly in his life, “I think they may have been not human beings, but wayward angels.” Angels and demons again, and a Last Judgment: “When I die myself, BD and Dundun, the angels of the God I sneered at, will come to tally up my victims and tell me how many people I killed with my blood.”

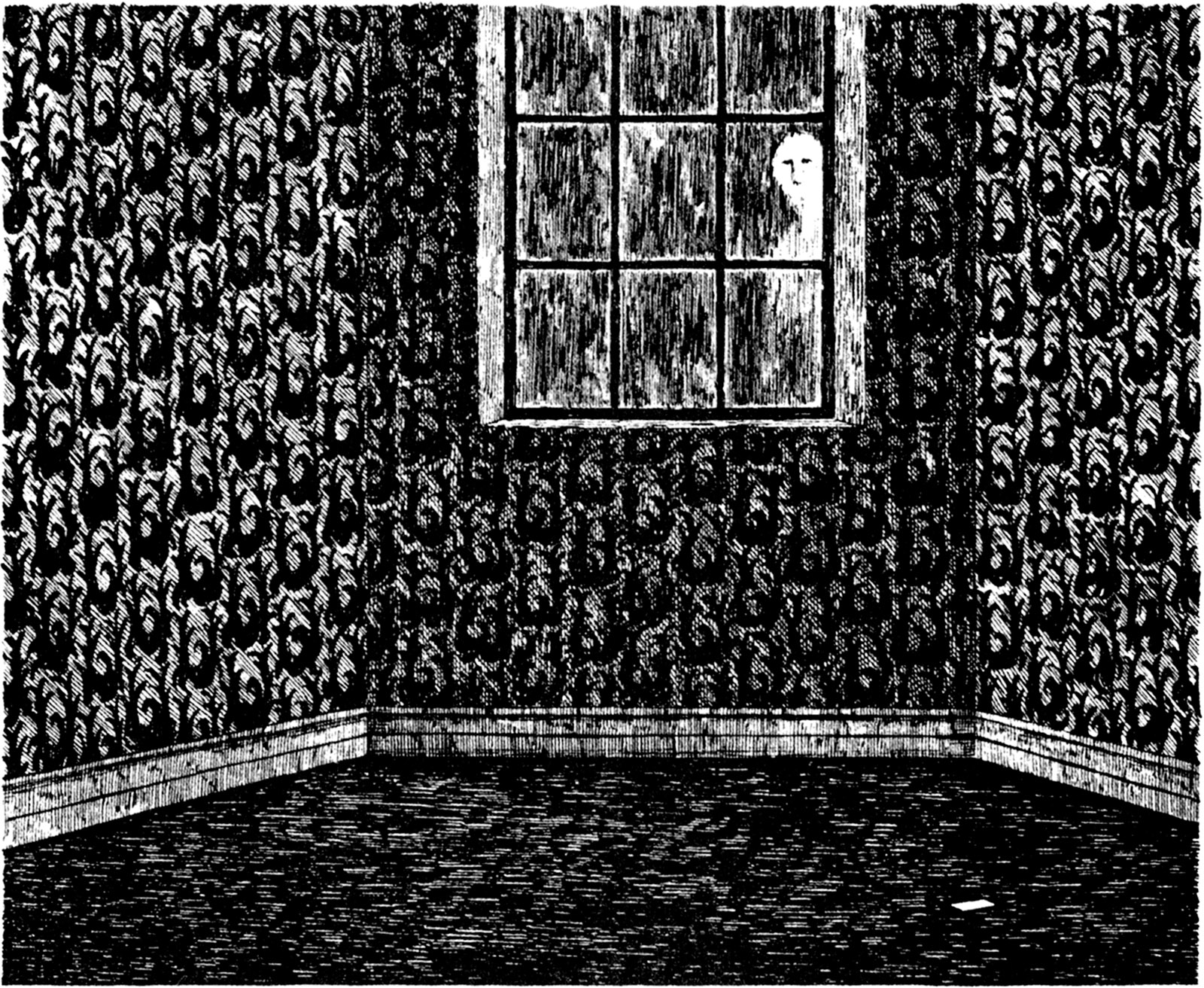

“Triumph over the Grave” is essentially a ghost story, in which Darcy Miller—D. Hale Miller—sees people who aren’t there: “No,” he argues, “they’re not ghosts. It’s them. They’re alive.” His friend says, “Even though they’re both dead and buried,” and Darcy says, “Yeah.” The subjects of the final story are grave robbery, Elvis’s double, and selling out. You finish the book with all the laughter caught in your throat and slightly appalled by the quantity of suffering that had to serve as the source of the art.

Visiting a seminar I was teaching at the University of Minnesota in April 2012, Denis Johnson was kind, generous, and a bit remote, as if he was preoccupied by something he would not say. In answer to a question about his influences, he named Fat City, Leonard Gardner’s novel about down-and-out boxers in Stockton, California. “Most books fail,” he said with a thin smile and a shrug. “But not that one. I read it so often, I almost memorized it.” When asked what he had been reading lately, he replied, “the Bible.” That night he read from his novella Train Dreams, a tenderhearted story of spiritual loneliness, one of his best works. Afterward, he answered questions from the audience, as most contemporary authors are forced to do now. Despite his affability, he gave the impression of being elsewhere.

I always thought that Denis Johnson was one of the most gifted writers of his generation, and The Largesse of the Sea Maiden reinforces my admiration for his work. But despite its artistry, or maybe because of it, the book is harrowing to read, and the experiences depicted in its pages are those that you would not wish on anyone.

This Issue

April 19, 2018

A Mighty Wind

The Question of Hamlet

More Equal Than Others