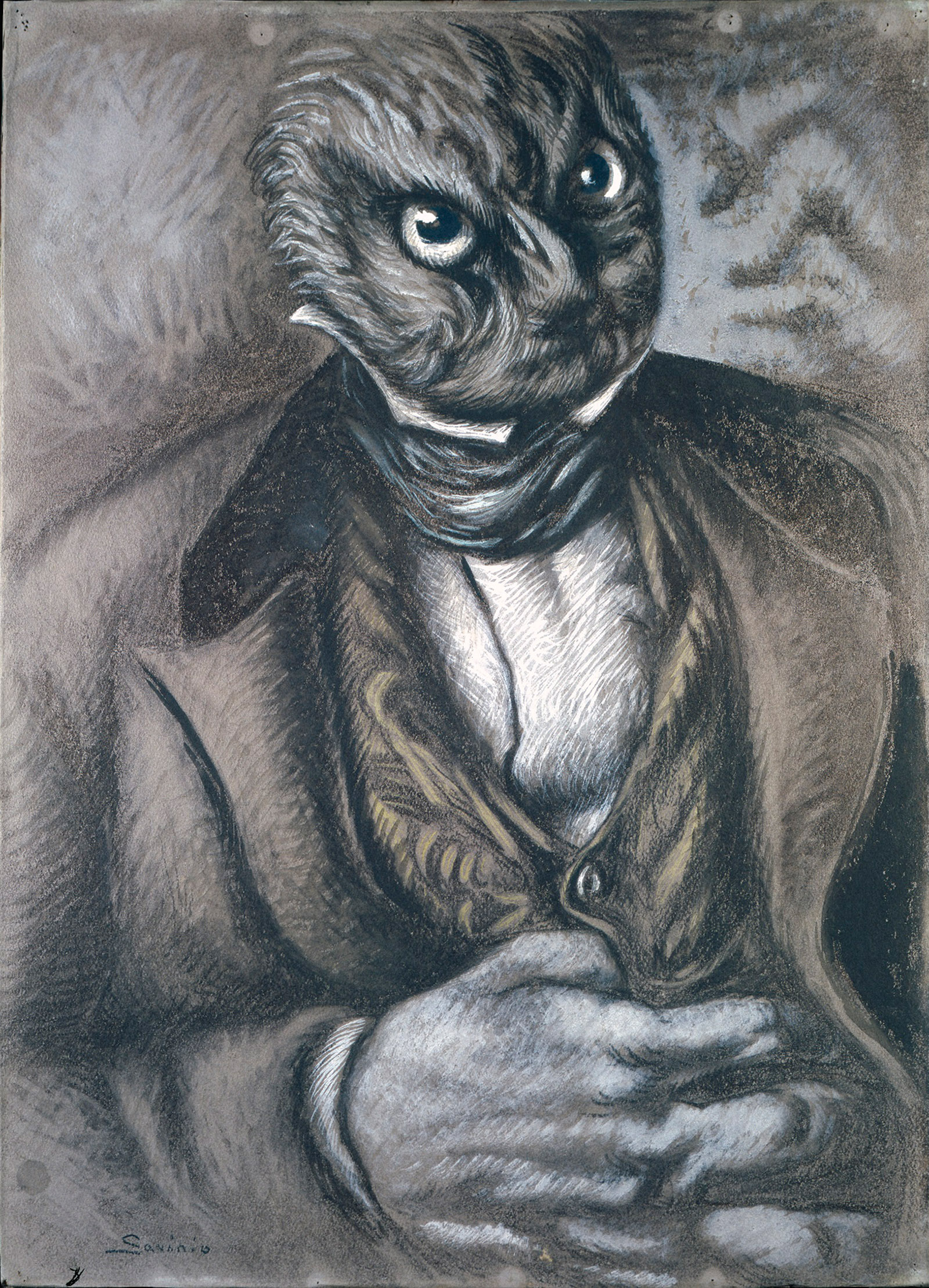

Alberto Savinio, the hidden spring of metaphysical modernism, lives on in his Self-Portrait as an Owl (1936). His face, with its marked eyebrows, dark eyes, thin lips, and air of melancholic diffidence, sketched in swirling feathers, resembles that of his brother, Giorgio de Chirico, who did a pencil drawing of the two siblings—or Dioscuri, as they liked to call themselves, after the mythical twins Castor and Pollux—at the start of their working life in Paris, one as a musician, the other as an artist. In Self-Portrait, Savinio wears a dark suit, and his shapely hand, the thumb hooked over a waistcoat button, takes up one fifth of the image. The scarf wound around his neck partly conceals a feathered chest (see illustration on page 29).

In his autobiographical novel, Childhood of Nivasio Dolcemare (“Nivasio” is an anagram of “Savinio” and dolce mare means “sweet sea”), Savinio wrote that the “singularity” of his alter ego “was so discreet, so secret, so subcutaneous, that on the surface nothing transpired and might easily have been mistaken for the most blatant normality.” André Breton, in his Anthology of Black Humor, baldly stated that “the basis of all modern myth still coming into being is founded on two bodies of work, Alberto Savinio’s and that of his brother Giorgio de Chirico, almost indistinguishable in spirit, that reached their climax on the eve of the 1914 war.”

Savinio, the younger brother, was a composer who wrote novels and stories, as well as essays on literature, art, theater, opera, and ballet. He was also a stage and costume designer. And he was a painter. That’s the side of him on view at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA), in Soho, where twenty-five of his rarely seen works are on display. There are two galleries at CIMA: the larger one holds depictions of toy-like forms, the smaller one Savinio’s portraits of his family.

Savinio said of his paintings that they were “born even before they were painted.” Most of those in this show were made between 1926 and 1936, during his second stay in Paris, although two small lithographs are from 1945 and 1946. In one of these, My Parents (1945), his mother and father have become stone armchairs, very expressive ones, with just one eye each. The mother’s chest looks pubescent above an exposed ribcage, her arms replaced by a rolled upholstery trim, her head the skull of a camel or a horse. The father is headless, an expansive chest grafted onto an armchair with one immense, mournful eye staring out of it. The shadows they cast consist of dense handwritten lines that narrate a brief story of their lives: “My mother was called Gemma, she sang with a beautiful mezzo-soprano voice.” In his father’s shadow, Savinio wrote:

One day while we were having lunch, my father suddenly got up from the table, walked quickly to the window, flung it open, leaned out, then opened his mouth as though to address a crowd below. He was in fact throwing up all the food he had eaten. That speech to an invisible crowd was an intimation of his death…. My father stood before me like a mountain I had to go beyond.

Giorgio de Chirico was born in 1888 in Volos, Greece. His brother, Andrea, who changed his name to Alberto Savinio in 1914, was born in Athens in 1891, six months after the death of their older sister, Adele. Their father, Evaristo de Chirico, a Sicilian nobleman, was chief engineer for the construction of the Thessaly railway. He died in 1905, and Alberto, who was then fourteen and had won first prize at the Athens Conservatory two years earlier, composed a requiem for his funeral.

According to de Chirico, their mother, Gemma Cervetto, was a Genoese noblewoman, but she may instead have been a former cabaret singer from Izmir, according to the Savinio specialist and art dealer Paolo Baldacci.1 After strictly supervising the boys’ home schooling, Gemma decided to take the family to Munich so that de Chirico might study at the Academy of Fine Arts and Savinio could take lessons from the composer Max Reger. De Chirico accompanied his brother, whose German was less proficient, and it was in a catalog at Reger’s that they discovered the Swiss symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin, who depicted peculiar things as though they were perfectly normal, such as a centaur stopping in a village to have a hoof reshod.

In Athens, the de Chiricos had been part of a diplomatic circle that included plenipotentiary ministers from Germany, Austria, and Russia, and a sprinkling of barons, countesses, even a princess. In Savinio’s Reception Day (1930), these lofty specimens have metamorphosed into an ostrich, a hawk, an eagle, and a pelican done up to their feathery nines and so enlarged in their preening as to fill an entire window frame. In Nivasio Dolcemare, Savinio denounced the aristocracy’s “boundless idiocy,” though elsewhere he conceded that “the primary aristocratic quality is a natural aptitude for synthesis.” But he understood that “a man destined for higher things must overcome the characters of his family, background, and race—life’s ‘picturesque.’” His way of doing so was to spend half a lifetime narrating and portraying that very family.

Advertisement

He painted his parents as if they were photographs turned into statues, gray and stony, while his colorful geometric compositions are always animated and in a state of compressed turmoil. In Untitled—Couple and Infant (1927), Evaristo de Chirico has a beard that juts out on either side of his jaw like puffs of smoke from a locomotive, while in Family of Lions (1927), a double portrait of Savinio’s parents, a lustrous long black locomotive crosses the picture frame behind them and looks more alive than they do.

Savinio defined his own Surrealism as “lending form to the formless and conscience to the unconscious.” He might have added that he didn’t mind draining living subjects of some of their life: in Portrait of a Child (1927), adapted from a photograph of Giorgio de Chirico as a boy, the gray-and-white figure stands stock still, wearing a droll little white frock, and stares up out of one eye, the other an empty socket, the mouth set in a pout. Directly behind him is a dark-brown, container-like shape, a palpable shadow, a blank monument, or one seen from the back, which perfectly mimics the figure’s outline—the ruffle of the skirt, the curve of a shoulder. The background is populated by cumbersome geometric volumes shaded, or daubed, in different arrangements of colors and patterns—each a diminutive abstract painting in its own right. The clouds are scribbled white masses that Cy Twombly might have painted.

The family, the furniture, the clothes, the mores are statically Victorian, as though they were embalmed—in memory and through the eternal stillness of photographic captivity. The sea, which appears in many of Savinio’s paintings, is unbridled and moody and very much inspired by Böcklin’s roiling seas, as Savinio’s graphic blocks might have been by Böcklin’s bare and abstract-looking rocks, except that Savinio covers the surfaces of his geometries with riotous though always controlled patterns. The Enchanted Island (1928) shows a cheerful cemetery-like huddle of objects from some future time perched on top of a mostly submerged rocky mountain that seems to be swaying; gridded, dotted volumes and slabs are massed together in a sort of post-earthquake composition in which they appear to exist in happy communion.

All the paintings in the main gallery are full of life: in Marine Ride (1929), a boat-like jumble of purple, yellow, and red objects seems to be powered by brown and blue bursts of vapor burgeoning up into the sky. In The Wise Men (1929), a flying monument made of quivering crayon-colored stars, spirals, and shapes reminiscent of jelly beans, pastries, and icing (long before Wayne Thiebaud) is poised on a self-propelling raft cruising above a deserted landscape. Streamers convey the impression of movement. These are eerily giddy paintings, odes to childhood that, through sheer painterliness, turn trifles into things deserving to be looked at, not unlike William Eggleston’s photograph of a tricycle shot at an angle that makes it appear monumental and so, in some way, metaphysical. They allude to the mystery that both Savinio and De Chirico were so bent on representing.

In Atlas (1927), the artist’s mother, gazing absently, is sitting on a stage in her favorite armchair (Savinio wrote a story titled “Poltromamma,” or mom-armchair). A huge brown lizard with bloodshot eyes and an admirable row of teeth erupts from her primly clad lap. Savinio might have identified with the prehistoric beast, comically charging into the world, perhaps in search of the opposite of “seriousness,” which he ridiculed. In his introduction to an edition of Tommaso Campanella’s 1602 utopian treatise, The City of the Sun, he hoped that his readers might have “overcome the prejudice of seriousness, which spreads so much darkness over matters of culture and life in general, and know now that seriousness is an obstacle and a limitation, and therefore a form of unintelligence.” The optimal condition for the modern mind, he believed, was dilettantismo, the state of knowing that “life is not a problem.”

But in Milan, at the age of sixteen, trying to sell his first opera, Carmela, to an Italian music publisher, and beginning to compose a new one, Savinio was actually quite serious: he studied Greek, Latin, literature, philosophy, and music. He wrote a fifty-page annotation of the ancient Greek epic Argonautica, which his brother saw when he visited Milan. A year later, de Chirico painted The Departure of the Argonauts (1909). In those early years, Savinio and de Chirico also discussed the works of Schopenhauer and Otto Weininger, the Austrian philosopher and author of Sex and Character. Their “Metaphysical Art”—as the brothers, together with the painter Carlo Carrà, named it in 1917—owed some of its inspiration to these thinkers. When Savinio was eighteen, he read Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo (in French, though he knew some German, since it was “not a book to be read with a dictionary at your side”). It confirmed what he already knew—that “to be just ‘a man’” was to be “more than ‘a Christ.’”

Advertisement

Before turning to music, Savinio had told people that he wanted to be a priest. In Nivasio Dolcemare, he wrote that if the apse of the Catholic church of Saint Dionysius the Areopagite in Athens, where he was baptized, had been painted by Cézanne instead of a certain Ermenegildo Bonfiglioli, “given to Tiepolesque rotundities,” he might have become “a theologian, a missionary, even a high minister of the church.” Before the image of an enormous eye inside a triangle in the apse of another church, his governess, Frau Linda, an impoverished German violinist, snorted, “Paintings, pfui! God is all psyche. No need for portraits!” But Nivasio/Savinio was touched by the image of the eye in the triangle and snuck back to the church that night bearing provisions for the “Greek God,” as he called him, only to be met by a slap from Frau Linda, huddled behind the altar. There and then he chose the Greek God over the Catholic one: “If the Greek God is praying, who could he be praying to if not to himself?… The prayer of a God faithful to himself seemed to him a prayer par excellence, the prayer of all prayers.”2

Savinio ironically summed up his own stories as “among the most singular and profound of any written in Italian,” adding that some of them “cast armchairs, sofas, cupboards, and other furniture, as sensitive characters, that could talk and act.” Pianos shudder to play less than worthy compositions, or they have warm tails and give birth overnight to a multitude of little pianos that subsist on a diet of meat and vegetables and are soon climbing over the furniture, hiding behind curtains, and “playing like puppies.” In Paris in 1914, in an early instance of performance art, Savinio, in shirtsleeves, assaulted a piano in his proto-Dadaist composition Les chants de la mi-mort.

The performance took place at the offices of the literary review Les Soirées de Paris, where Guillaume Apollinaire was the chief instigator of a nascent avant-garde. Picasso, Alexander Archipenko, de Chirico, Blaise Cendrars, and other prominent members of the Parisian art scene were present. Apollinaire raved about the performance in the Mercure de France:

I was fascinated and at the same time amazed because [Savinio] abused the instrument he was playing to such a degree that, at the end of each work, pieces of the upright piano fell off, so that another piano had to be brought in, and was immediately smashed to pieces. I am certain that within two years he will have demolished every piano in Paris. After that he can travel the world demolishing all the pianos in the universe—and that might be a good riddance.

Jean Cérusse (aka Serge Férat), the music critic for Les Soirées, reported on the “singular spectacle of shouting, contortions, arms flailing and fists punching the piano until blood oozed from the young musician’s fingers.” The sets and costumes were also by Savinio. (Toward the end of his life he would design several opera productions for La Scala in Milan.)

Savinio wrote in the program notes that his music was “de-harmonized” and that its structure was essentially based on drawing: “Each of the drawings is repeated two, three, even four times, according to the ear’s natural inclination; and after a pause of one beat, a different drawing immediately appears.” It is an early example of atonality, and Savinio’s suite for Les chants de la mi-mort, considered revolutionary by Apollinaire, has been seen as a precursor to compositions by Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez.3 Savinio wrote that he “withdrew from music in 1915 at the age of twenty-four out of ‘fear.’ So as not to totally give in to the will of music…. Because music stupefies and stupidifies.”

Nineteen fifteen was also the year that Italy entered the war, and the brothers joined the army so as to finally obtain Italian passports. They were sent to Ferrara, where they were at first briefly admitted to a military hospital for nervous disorders. It was here that they met Carrà. Then Gemma and her sons set up house in Ferrara, “the city of geometric lechery,” in Savinio’s words. Two years later, Savinio was dispatched to Thessaloniki as an interpreter, which prompted the diary later published as The Departure of the Argonaut (1918). In Ferrara the brothers saw a lot of Carrà and the artist Filippo De Pisis. A decade later, after Mussolini’s Fascist regime had firmly established itself, de Chirico’s painting was attacked by his ex-friend Carrà as “the stuff of beginners,” and Savinio, in the same paper, was characterized as “un ebreo sospetto” (“possibly a Jew”) without a distinct nationality, a failure both as a musician and as a man of letters, and essentially anti-Fascist. The brothers’ cosmopolitanism rendered them suspect in the eyes of Fascist nationalists.

De Chirico wrote a letter to Mussolini stating his loyalty to the regime and started telling people that he’d been born in Florence (he had much to fear since his second wife was a Russian Jew), while Savinio published a disquisition on his family’s Catholic roots.4 They left Italy for Paris, where they were welcomed with open arms, and missed no opportunity to belittle the “nonexistent” Italian art scene. De Chirico’s show in 1918 at the Paul Guillaume gallery, featuring fifty-five early works depicting figures frozen into monuments or mannequins and vast unpopulated architectures steeped in otherworldly stillness, was greeted with enthusiasm. Nothing he painted after that show has been considered as innovative as those first metaphysical paintings, although a handful of writers and artists accepted his new neoclassical manner as a parallel to Picasso and Braque’s shift away from Cubism to a new figuration (as in Picasso’s Two Women Running on the Beach, or Braque’s still lifes) and viewed him as one of the greatest exponents of modernism—something Savinio never achieved.

The influence of the two brothers on each other has been a source of much speculation among art historians. De Chirico recorded in his memoir that Alberto was drawing, painting, and composing early on in Milan. One of Alberto’s drawings, The Oracle, was almost certainly made in 1909, around the time that de Chirico painted his seminal picture The Enigma of the Oracle (1909). Both works represent a headless, draped statue, a curtain, a seascape, and dense clouds. Giorgio himself was writing music, too. Clearly, their personal and artistic lives were intertwined. Both brothers aimed for a juxtaposition of autobiography and antiquity.

Savinio was the first of the two to visit Paris, in 1911. A respected musician of Greek origin introduced him to Erik Satie, Paul Reverdy, Jean Cocteau, Picasso, Max Jacob, and Apollinaire. But when Savinio sent his brother some of his studies for paintings in 1926, it was de Chirico who invited Savinio to join him in France. Savinio was married to the actress Maria Morino, a former member of Eleanora Duse’s company, who had starred in an unsuccessful ballet of his in Rome. De Chirico’s first wife was the Russian lead ballerina from that same production.

Savinio had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Jacques Bernheim in 1927. Cocteau wrote the text for the catalog and designed its cover. Of the twenty-six paintings shown, eighteen were sold to important dealers and collectors. A few years later Savinio, his wife, and their daughter, Angelica, returned to Italy, where they had another child, Ruggero. Savinio continued to paint and built himself a small modernist house near his beloved sea—in Poveromo, near Forte dei Marmi. He wrote many books, a great deal of modestly paid journalism, and had two important exhibitions of his paintings, in Turin and in Milan.

Savinio would not have liked to be seen as the greater artist overshadowed by a histrionic brother. Neither one could have existed without the other. They remained close until de Chirico met Isabella Pakzwer Far, who became his second wife. Then their mother, Gemma, died in 1937, a further rift in the symbiotic union of the Dioscuri. They were metaphysically reunited after Savinio’s sudden death in 1952 at the age of sixty in Rome. Stunned at his brother’s straitened circumstances, de Chirico laid a laurel wreath on his remains and two years later, in Rome, curated the most complete exhibition of Savinio’s paintings, some of which are now on display at CIMA. “It is in death,” Savinio predicted, “that my brother and I will go back to being as we were twenty or so years ago, when nothing had yet divided us, and though there were two of us we shared a single thought.”

-

1

Alberto Savinio: Musician, Writer, and Painter, edited by Paolo Baldacci (Paolo Baldacci Gallery, 1995). ↩

-

2

De Chirico later said that one had to “find the demon…the eye in all things.” ↩

-

3

See Sergio Macedone, Come un pesce nel boccale—Alberto Savinio, la musca e la metafisica, October 16, 2016. ↩

-

4

In fact, the de Chiricos may have been a little bit Jewish. Their paternal grandfather had married a countess whose uncle, a Spanish merchant, had converted from Judaism in order to establish ties between Catholic Spain and the Muslim Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century, for which he was granted a title. For more on the subject of the brothers’ Jewishness, see “L’Ora ebrea di Giorgio de Chirico—Pittura metafisica e primitivismo semitico: 1915–1918,” in Ara H. Merjian, De Chirico a Ferrara: Metafisica e avanguardie (Ferrara: Fondazione Ferrara Arte Editore, 2015). ↩