The immediate future of Italian politics is now in the hands of a famous comedian whose party might form an alliance with a far-right party that once advocated the secession of the northern regions of Italy. Both parties share an antagonistic attitude toward the European Union. How did all this come to pass?

In the early 1990s Italy’s GDP equaled or even surpassed that of Great Britain, making it the world’s fifth-largest economy. This was all the more remarkable given that the cold war had frozen Italian politics; the presence of the largest Communist Party in Western Europe had prevented the normal alternation of left and right governments. This led to virtual one-party rule by the Christian Democrats, a deeply entrenched patronage system, and widespread corruption. However, the European Union’s standardization of currency and a nationwide investigation into political corruption were expected to rein in government profligacy and waste, strengthen democracy, and encourage economic prosperity.

This did not happen. Today, Italy’s GDP is 36 percent smaller than the UK’s—the result of twenty-five years of economic stagnation. Despite a slight recovery in the past two years, Italy’s GDP—and the average Italian family’s purchasing power—is still more than 10 percent smaller than it was before the recession of 2008–2009. Unemployment is over 11 percent and about 33 percent for people under twenty-five who are not in school. Those who do find work are barely scraping by. According to the Bank of Italy, 30 percent of Italians thirty-five and under earn about $1,000 a month, forcing them to live with their parents, delay or forgo having children, or leave the country. Nearly two million people—most of them young, educated, and skilled—have left in the past ten years.

It is no surprise, then, that Italian voters in the national elections on March 4 rejected the parties that have run the country for the past generation. The chief beneficiaries of this general disaffection were two protest parties. One was the Lega, which ran on the promise of kicking out the country’s estimated 600,000 illegal immigrants and won nearly 18 percent of the vote. But the biggest winner—at 33 percent—was the Five Star Movement (FSM), founded by the comedian Beppe Grillo.

The FSM is another expression of the populist wave that has swept so many Western democracies in the past several years. It has a loud, foul-mouthed, and charismatic leader who dares to say what others only think; it makes innovative use of digital technology and social media; it advocates economic protectionism; it stokes anti-immigrant sentiment, violent anger at the traditional press, and skepticism of established experts and professional politicians. And it has a soft spot for Vladimir Putin.

The FSM also draws on left-wing populist ideas: a guaranteed minimum income, environmentalism, and a deep distrust of global capitalism. It has developed new forms of political participation and expressed a strong idealistic desire to clean up politics, limit the power of professional politicians, and use the Internet to make politics more responsive to ordinary citizens. How a blog started by a stand-up comic has become the largest party in one of Europe’s largest countries is worth serious attention, both for what it portends for Italy and for what it suggests about our time.

The origins of the Five Star Movement can be dated to April 2004, when Beppe Grillo reached out to a Milanese Web guru named Gianroberto Casaleggio (who died in 2016) because of something he had written about the potential of the Internet. Casaleggio proposed making a website for Grillo, which he swore would soon be the most important blog in Italy and change the nature of the country’s politics. Grillo, who had no idea what a blog was, hesitated, especially when he heard that it would cost €130,000. But Casaleggio offered to set it up for free if his company could recover its costs by using the site to sell Grillo paraphernalia like T-shirts and DVDs.

Casaleggio had worked as an executive at Italy’s largest telecommunications company and had his own Internet marketing firm (Casaleggio Associates). Part hippie, part high-tech anarcho-libertarian, he had granny glasses and a mane of frizzy hair, but he was also a tough corporate manager with a low tolerance for error. Casaleggio and Grillo regarded traditional politics and international economic inequality with disgust. Instead they had faith in the Internet, which in their 2011 book Siamo in Guerra: Per una nuova politica they celebrated for its “Franciscan, anti-capitalist” potential. At the same time, Casaleggio had a dark, apocalyptic side. In one of his videos he predicted that a world government of direct Web democracy would eventually triumph after a brutal nuclear war reduced the world’s population to an eighth of its present size.

In a shockingly short time, www .beppegrillo.com became not just the most popular blog in Italy but one of the biggest and most influential in the world. The few Italian politicians who already had websites did not use their interactive features or encourage visitors to leave responses. Grillo—and Casaleggio, who frequently ghostwrote for him—posted a new item every day, often provoking hundreds or thousands of comments. They discussed political corruption, the excessive power of banks and multinational corporations, the garbage crisis, and the danger of public incinerators. For Italians, especially younger ones who felt ignored by Italy’s main political parties, the blog became a channel for growing political frustration.

Advertisement

Casaleggio had studied the insurgent presidential campaign of Howard Dean in 2004 and online political groups such as Moveon.org. From them he borrowed the idea of organizing “meetups” where readers of the Grillo blog (“friends of Beppe Grillo”) could discuss issues in person. Grillo himself occasionally joined these meetings during his frequent stand-up tours. Readers’ comments about local scandals and stories gave Grillo fresh material for jokes he included in his performances. Readers and spectators felt they were actively collaborating with him on a great project.

Grillo developed his style of satirical comedy on Italian TV during the 1970s and 1980s. He became infamous for a joke he made on air in November 1986, when the Italian Socialist Party was at the height of its power and already notorious for its corruption. The Socialist prime minister Bettino Craxi was then on a state visit to China. Grillo imagined an aide turning to Craxi and asking: “If they are all socialists here, who do they steal from?” The joke got Grillo kicked off RAI, the Italian state TV channel, which was, and still is, under direct government control.

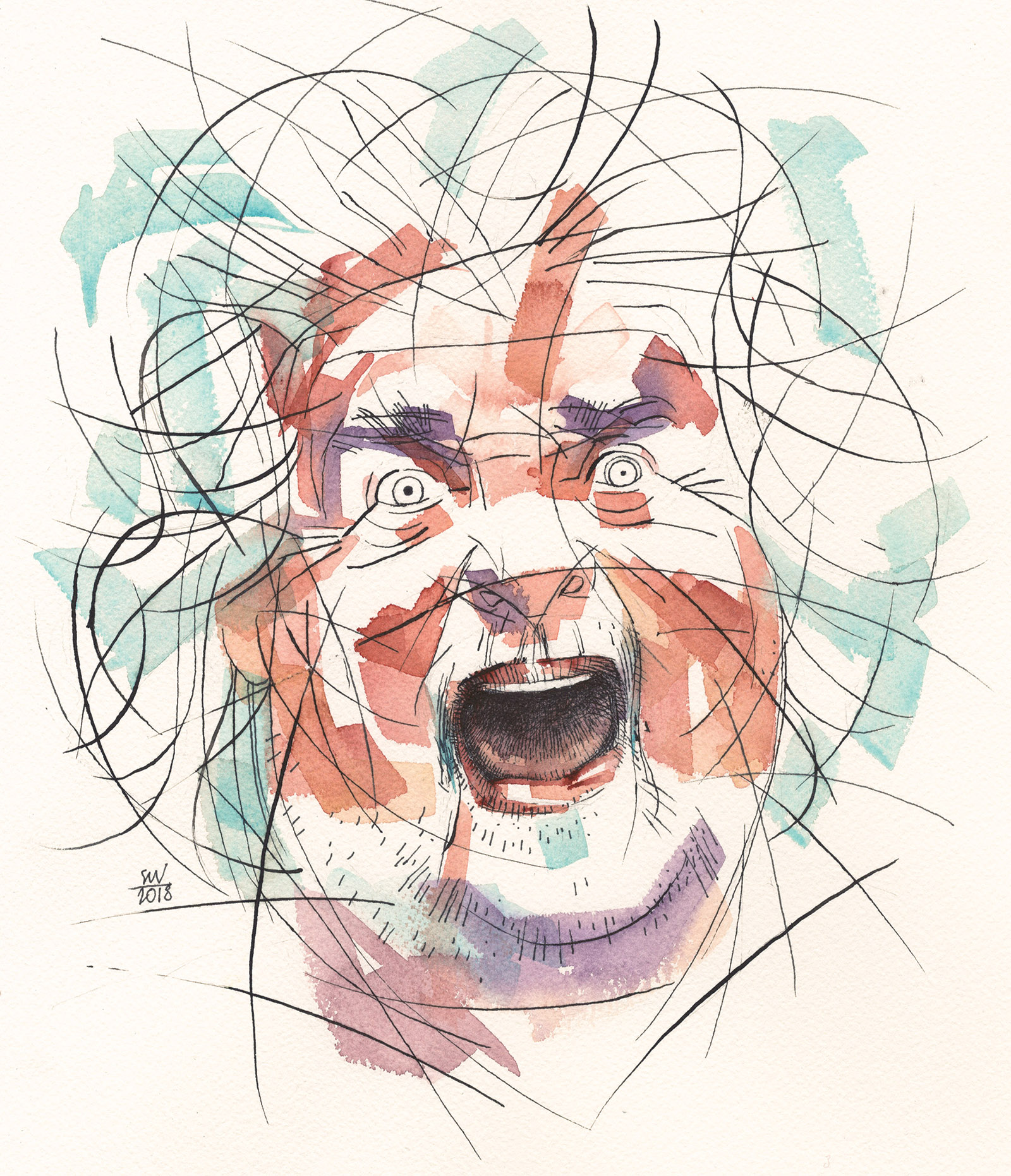

Banishment from RAI has destroyed the careers of many performers, but it turned Grillo into a political martyr. Seemingly unfazed, he started touring Italy relentlessly. His comedy routines became increasingly like political monologues: long harangues about the evils of multinational companies, the waste and stupidity of contemporary life, the undemocratic nature of the European Union, the greed and moral turpitude of the country’s politicians. His brand of humor—heavy sarcasm, indignant explosions of rage during which he might read the ingredients of a popular mouthwash or smash a computer on stage—is difficult for a non-Italian to understand. (I confess that I have watched hours of Grillo performances and managed only a few chuckles.)

As Oliviero Ponte di Pino writes in his shrewd short volume Comico e Politico, Grillo speaks to the “stomach” of ordinary Italians. With the heavyset build of someone who enjoys his pasta, a scruffy beard, and a broad, vulgar sense of humor, he looks and talks like an Italian Everyman. He is also shrewd and cynical. His laments about the ills and absurdities of Italian life and the dark forces of international capitalism sound like more sophisticated versions of the tirades you might hear from someone holding forth at your local Italian bar.

Italy’s tradition of political satire dates back to a time when criticizing power directly was illegal and dangerous. In papal Rome, ordinary citizens pinned poems with bitter and vulgar humor about abuses of power to the statue in Piazza di Pasquino. Ponte di Pino compares Grillo to the clowns in the Italian commedia dell’arte, who insulted common adversaries in order to make their audience laugh. The critic Marco Belpietro has written that Grillo reminds him of the stock character Pulcinella, “whose comedy, based on derision and put-downs of the adversary, was the best weapon in winning the sympathy and laughter of the public.”

In some of his theatrical shows, Grillo mixed scientific fact with crackpot theories. For a time, they were filled with tedious rants about how vaccines were nothing more than a mechanism to sell people useless drugs. Grillo pushed a supposedly miraculous cure for cancer that was found to be useless, and he claimed that HIV was invented by pharmaceutical companies. But he also raised valid concerns that the mainstream press ignored, denouncing, for instance, the shady practices of the national dairy company Parmalat years before it failed.

The chief prosecutor of Naples once asked Grillo how he had found out that the national phone company was illegally profiting from the use of erotic and astrological chat lines—a fact he had discussed on television. Grillo responded that it was mentioned in the financial disclosure forms the company made to stockholders, which evidently few people bothered to read. “With his mocking invective, Grillo denounced realities before both the press and the magistrature, not to mention the political world,” Ponte di Pino writes.

In 2007, the Grillo blog took a decisive turn toward becoming a political opposition movement. By then it had become clear that the nationwide investigation into political corruption of the early 1990s had failed to deter further violations. Since he entered politics in 1994, Silvio Berlusconi had filled parliament with business cronies who hoped to avoid prison by gaining parliamentary immunity.

Advertisement

Grillo called for a national day of protest in September 2007 called “V-Day,” short for vaffanculo (slang for “fuck you” or “up yours”), the culmination of a “clean parliament” campaign he had begun two years earlier. It was part political demonstration, part happening, part theatrical performance. Grillo assembled a huge crowd in Bologna’s central square, which was live-streamed onto video screens set up in piazze in 220 other cities and towns across Italy, and led a unified chant of vaffanculo! to Italy’s political parties.

V-Day combined anger and vulgarity with perfectly sensible and even modest political demands: that no one should stand for parliament who had been convicted of a crime or indicted; that members of parliament should be limited to two terms; and that voters should be able to choose individual representatives for parliament rather than voting for a list composed by party leaders. Although the mainstream press—especially Italian television—hardly covered the event, at least two million people showed up. It was one of the biggest public demonstrations in Italy in decades.

After V-day it was obvious that Grillo, with Casaleggio behind the scenes, had created a national political phenomenon. They announced the formation of the Five Star Movement in 2009. It attracted members from both political parties, although somewhat more from the left, as the political scientists Roberto Biorcio and Paolo Natale report in their book Politica a 5 stelle. Many of Grillo’s supporters are young, working-class, and ecologically minded; they tend to favor tougher immigration policies and the right to armed self-defense. They are something of a mix between young Bernie Sanders voters and working-class Trump voters.

When the FSM ran candidates in various local elections in 2010, 2011, and 2012 with modest results, it was dismissed as a passing fad. In 2013, however, the movement captured roughly 25 percent in the national parliamentary elections, depriving the center-left Democratic Party (DP) of a working majority in parliament. When Grillo and Casaleggio refused to cooperate with it, the DP was forced to form a government with Berlusconi, which damaged its public image and limited its ability to carry out a center-left reform agenda. Meanwhile, the FSM steadily benefited from the government’s unpopularity.

Now that it has the biggest share of power in the country, can a protest movement that steadfastly refuses to call itself a political party make good on its promise to change the very nature of politics? Casaleggio and Grillo once believed that the Internet would give them the power to replace traditional party politics with a new form of direct digital democracy. They set up a system in which activists could decide the party’s programmatic policies by contributing to online referenda. FSM members of parliament make legislative proposals, post short videos explaining them, and then party members post comments and vote for or against the proposals. “The concept of leaders is a curse word in the world of the web,” Grillo and Casaleggio wrote in Siamo in Guerra. “The political programs will be written by the citizens and every new point must be approved before being carried out.”

In practice, this form of direct democracy has turned out somewhat differently. The FSM used to be run on a website owned by Casaleggio Associates, a private consulting company that may do business with or represent corporate clients (Amazon, Google, Expedia) at odds with the FSM’s own political views—a significant potential conflict of interest. Grillo refuses to have a neutral third party monitor the online voting system or consider alternative direct democracy systems, such as the “Liquid Feedback” platform developed by the Pirate Party in Germany (an open-source platform that allows members to propose and debate issues and legislative motions).

In response to criticisms of its lack of transparency, last year the FSM separated its online platforms from Casaleggio Associates and created a not-for-profit entity called the Rousseau Association that now oversees the movement’s polls and deliberations. During the election campaign, someone leaked a document indicating that the Rousseau Association is controlled by Davide Casaleggio, Gianroberto’s son, and that it operates out of the offices of Casaleggio Associates. The new setup seems even more opaque than the old one and leaves the unelected Davide Casaleggio in a position of significant power.

The FSM is built on an ethos of egalitarianism—one of its mantras is “everyone is worth one”—but its online discussions and voting results tend to be shaped by a small number of influential figures. Of the 10.7 million people who voted for the FSM at the ballot box, only about 140,000 (1.3 percent) are registered with the website. Unlike other parties, FSM holds internal primaries to pick parliamentary nominees, but the number of people who vote in them is often laughably small. One candidate for parliament was decided with 57 votes, and the FSM’s choice for prime minister, Luigi Di Maio, received a mere 490 votes in his online primary for the 2018 election. Participation in online deliberations has declined steadily from 2012 to 2017, falling from an average of 36,000 to 19,000 participants. Because the movement has grown considerably in that time, the decline in the rate of participation is even more drastic: from 68 percent of eligible members in 2012 to a mere 13 percent in 2017.

In their book Supernova: Com’è stato ucciso il MoVimento 5 Stelle, Marco Canestrari and Nicola Biondo, two disillusioned FSM insiders, recount a disturbing episode in which Casaleggio, annoyed at the generally sympathetic attitude on the blog toward clandestine immigration, published a post warning his supporters that Roma would soon invade Italy. “I was there that day when that post was thought up,” Canestrari writes. “It was a deliberate provocation with a precise aim: ‘We need to free the Blog of all these left-wingers who are starting to bust our balls. We need to clean house.’”

In 2013, when members of the Five Star Movement in the Senate proposed decriminalizing illegal immigration, Grillo and Casaleggio spoke out against the proposal on the movement’s blog. The matter was then put to a vote online. Surprisingly, a majority went against the founders, but the FSM’s members abstained from a vote in the Italian parliament that would have granted citizenship to children whose parents had immigrated but who had themselves been born on Italian soil and to children who had gone to school in Italy and had at least one parent with a legal work permit. As a result of the FSM’s abstention, the measure failed.

The current leader of the FSM is the baby-faced, thirty-one-year-old Luigi Di Maio, one of Grillo’s early supporters. But Grillo himself remains the “guarantor” of the movement’s overall direction. He retains ownership of the 5Star copyright, which he has used in recent years to excommunicate political opponents by denying them the right to use the movement’s name or symbol. When the FSM activists or elected officials have criticized Grillo or seemed to violate the party’s core tenets, they have been banished. The popular FSM mayor of Parma, for instance, was expelled after he came under criminal investigation. When some newly elected members of parliament spoke out in favor of negotiating with the Democratic Party in 2013 and 2014, they were expelled.

“In order to maintain unanimity within the movement the FSM undertook a ferocious campaign of expulsions, with banned members pilloried online and subject to mini-digital votes that were hardly democratic,” Ponte di Pino wrote last September in the online magazine Doppiozero. More than a quarter of the FSM’s representatives across both houses of parliament were expelled between February 2013 and January 2015. “The harsh treatment of dissent guarantees unanimity without weakening the movement,” Ponte di Pino observed. “In fact, it appears to strengthen [it].”

Grillo and the movement’s other leaders justified these heavy-handed tactics by insisting that they were necessary for maintaining the FSM’s integrity. In the movement’s conception of democracy, representatives are elected not to make decisions autonomously but to execute the popular will. Grillo barred FSM politicians from appearing on talk shows (several were expelled for disobeying) and forced them to give a third of their salary to the party’s micro-credit fund for small businesses. During the 2018 election campaign, it turned out that eight candidates for parliament had cheated the system by falsely claiming to have returned a third of their salary. They were expelled from the movement and immediately offered a place in the party of Berlusconi, who has never had a problem with people getting rich from public office. (They refused the offer.)

According to Canestrari and Biondo, the party’s strict rules for its members slackened in the last few years when a new ruling elite emerged within the FSM and started applying its guidelines more selectively. After banning several dissidents, the movement relaxed its rule on talk-show appearances and offered media training courses to a select number of FSM parliamentarians chosen to represent the party on TV. Deputies who have personal relationships with Grillo (or who were close to Casaleggio) enjoy special treatment. As the FSM assumed power, Canestrari and Biondo maintain, its policy came to resemble that of the regime in George Orwell’s Animal Farm: “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.”

The FSM has brought about some changes to the makeup of parliament in a country that has been described as a gerontocracy—one where powerful positions in business, government, and academia tend to be held almost exclusively by older men. The arrival of the FSM in the Italian parliament brought the average age from fifty-four to forty-five. It has also increased the number of deputies with a university degree and the percentage of female deputies.

Some of the FSM’s internal contradictions are the natural result of a protest movement trying to turn itself into an effective political party. There is a certain tension between Grillo and Di Maio, who campaigned hard to convince the moderate electorate that the movement was a responsible governing party, traveling to London and reassuring financial interests that the FSM was prepared to make compromises and would not pull Italy out of the European Union. Grillo seems to have put the brakes on this by insisting that the movement make no postelectoral alliances. The movement’s leadership, he has said, is “biodegradable”: it would disintegrate were it to achieve its aims. The FSM is not only a two-headed movement but also has two websites, Grillo’s blog and the Blog delle Stelle, on which Di Maio posts virtually every day.

In keeping with Casaleggio’s insistence that the FSM is “post-ideological,” members of the party have pushed a medley of small-scale initiatives that span the political spectrum: they have been harshly critical of the EU; they have criticized the left for what they consider its lax policies toward illegal immigration, but stop well short of the right’s full-throated call to deport 600,000 illegal immigrants. They are against the privatization of various public services, such as water, and oppose waste incineration, nuclear energy, and high-speed trains. But then, they support protections for local industry and a guaranteed minimum income, which may have been a winning argument for many voters in this latest election. In the past Grillo liked to say that a housewife who managed her family accounts could be treasury minister. During the 2018 campaign, Di Maio announced a shadow cabinet featuring experts in a range of fields, including young economists who advocate straying from the EU’s strict austerity measures without leaving the union altogether.

Since March 4, there has been an unusual degree of cooperation between the election’s two winners, the FSM and the Lega. They are exploring the idea of a governing alliance and have agreed to share responsibility for picking the leaders of the two houses of parliament, with the Lega in charge of the lower house and the FSM of the Senate.

Another possibility could be a government headed by a respected figure who belongs to neither party and would run the country until another set of elections can be held under a new electoral law more likely to produce a stable government. Grillo, in a recent interview, seemed resigned to the fact that his movement has to change in order to govern, as long as it doesn’t have to change too much. “The era of vaffanculo is over, but it is not the time for base compromise,” he said. “We haven’t changed our DNA…. We are a bit Christian Democratic: a little right, a little left, a little center. We can adapt to anything as long as we stay true to our ideas.”

As the FSM starts governing, it will have to meet different expectations. Matteo Renzi rocketed from a relative obscure career as the mayor of Florence to become secretary of the Democratic Party in late 2013, then Italy’s youngest prime minister in 2014. Promising national renewal and reform, his party won an almost unprecedented 40 percent in the European Parliament elections of 2014. He seemed invincible. Four years later, his party lost more than half of its electorate, which dropped to 18 percent, and Renzi was shown the door as party leader. If the FSM fails to reverse the country’s fortunes, its fall could be as swift as its rise

—April 11, 2018