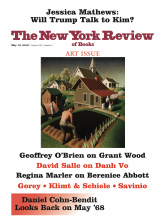

Grant Wood became famous pretty much overnight in October 1930, when American Gothic was included (a last-minute choice after being initially rejected) in the annual exhibition of the Art Institute of Chicago. The Chicago Evening Post slapped a photo of it on the front page of its art section under the headline: “American Normalcy Displayed in Annual Show; Iowa Farm Folks Hit Highest Spot”; the image was picked up by newspapers across the country, all quick to underscore the painting’s corn belt authenticity. Wood—whose most notable previous achievements had been successive first prizes in art at the Iowa State Fair—found himself at thirty-nine not only a celebrity but the embodiment of a movement, or at least the journalistic notion of a movement, steeped in patriotic overtones.

Few artists have been worse served by their defenders. “If you love America, you will love this show,” a newspaper critic wrote of his first New York exhibition. Boosterish critic Thomas Craven hailed him as “the only American artist who is perfectly adjusted to his surroundings.” Time ran a cover story upholding Wood as part of a revolutionizing wave also said to include Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, upstarts rejecting “deliberately unintelligible” and “outlandish” modernist abstraction in favor of plainly depicted American realities.

Among those defenders was the artist himself. Once in the spotlight, Wood, a bookish man known to his Cedar Rapids acquaintances as diffident in manner and halting in speech, applied himself dutifully to elaborating a “born-again” narrative of how he had rejected his early European influences and embraced homegrown sources of inspiration:

I began to realize that there was real decoration in the rickrack braid on the aprons of the farmers’ wives, in calico patterns and in lace curtains. At present, my most useful reference book, and one that is authentic, is a Sears, Roebuck catalogue.

He had made repeated trips to France and spent years mastering the techniques of Impressionist painting, yet could dismiss that experience with a sort of “aw shucks” reductionism: “I came back because I learned that French painting is very fine for French people and not necessarily for us, and because I started to analyze what it was I really knew. I found out. It’s Iowa.” He confided to the Herald Tribune that “all the good ideas I’d ever had came to me while I was milking a cow”—eliding the fact that he hadn’t lived on a farm since he was ten years old.

Nothing had prepared Wood for becoming a national figure. He can easily be imagined continuing the kind of career he had already achieved: a mainstay of the Iowa art scene, a skilled craftsman adept at shaping everything from tea kettles to fire screens, a jobbing artisan who could lend hieratic monumentality to an oil painting advertising model homes, enjoying the companionship of local literary friends like MacKinlay Kantor and Paul Engle, plunging energetically into community theater projects, showing paintings at local fairs and galleries, decorating houses and funeral parlors, designing murals for hospitals and department stores, and concocting such whimsical follies as the corncob-shaped chandeliers he created for the dining room of a Cedar Rapids hotel. When he developed in relative isolation the hard-edged style of his mature paintings and advanced beyond his essentially decorative early work toward increasing ambiguity and expressiveness, there was nothing inevitable about his sudden fame. He might well have gone on with no major recognition at all, and therefore without any pressure to live up to a public image that would become almost caricaturally at odds with who he actually was.

In the event, his acclaim came suddenly, fairly late in life, and he did not resist the myth-making process by which he was identified as a plainspoken all-American genius in overalls who had purged himself of exotic influences to express the pioneer values of the heartland. As a spokesman for his own work, he made himself a character in a public play, and not an especially convincing one. The acclaim was diminishing by the time Wood died in 1942, and his reputation, already vigorously contested in his lifetime, would largely dwindle to the inescapable fact of American Gothic, an image too deeply imprinted to be dislodged.

The Whitney has given him a fresh chance with a comprehensive retrospective of his work, “Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables,” but even here, with that work so generously spread out, it’s hard to clear away the encroaching entanglements of bygone culture wars, regional prejudices, and Wood’s own often inscrutable motives and circumstances. As the exhibition’s curator, Barbara Haskell, suggests in the catalog, Wood’s art may need to be rescued from its historical moment and its own declared intentions, the better to pick up on its undercurrents of “disquiet…estrangement and isolation…unsettling, eerie sadness.” To walk through the show is to experience not so much the Middle America he was alleged to celebrate but rather a peculiar country of his own invention. Craven’s “perfectly adjusted” painter survives by sheer force of oddity, and despite any countervailing tendency on Wood’s part to conform to an assigned role.

Advertisement

That it should have been American Gothic that turned his fortunes around is as mysterious as the painting itself now seems, laden with unfathomable accretions of association. The double portrait of the unsmiling Iowan with the pitchfork (farmer? townsman?) and his aproned companion (wife? daughter?) remains the most universally recognized American painting. (The models were Wood’s sister, Nan, and his dentist; the house with its distinctive churchlike arch was one that he happened upon in Eldon, Iowa.) It has been sculpted as a life-size replica at the Movieland Wax Museum in Buena Park, California, and used as the advertising motif for a gory 1988 horror movie of the same title. To Google “American Gothic parodies” is to plunge into a bottomless netherworld of distortion, defacement, and burlesque in which—in ads and political cartoons and magazines ranging from the AARP Bulletin to Hustler—the pair have been replaced by Mickey and Minnie Mouse, Barbie and Ken, the Clintons, the Obamas, the Simpsons, dogs, cats, rural pot smokers, same-sex couples, economically challenged retirees, Satanists, zombies, and thousands of other candidates. Trump-related iterations alone are beyond counting.

My own earliest encounter with the ubiquitous painting doubtless came through one such parody, quite probably (like so many such meetings with cultural icons) in the pages of Mad. Looking at the original now, it seems almost to have been a parody from the start, a pastiche of some fifteenth-century Flemish counterpart, in which every element—the formalized framing, the grave stiffness of its subjects, the stylized elongation of their heads—refers back by way of humorous contrast to an Old World model, perhaps to the very notion of fine art. I don’t think I’m alone in not having known quite what to make of American Gothic. Who were these people? What was the import of this painting? Why was it everywhere? The image imposed itself too early for there to be any question of liking or disliking it. It was there, an outlying oddity somehow definitively entrenched, folksy, quaint, even a bit menacing if you really attempted to look into the eyes of that terminally dour and unappeasable man, or tried to imagine what the woman was feeling—fear? discontent? a shared sorrow?—or exactly where her gaze was directed.

Back in the 1930s the painting struck viewers with a poster-like immediacy, even if critics of different persuasions came up with opposite readings. It was equally easy to see Wood’s pair as embodiments of a sturdy and sober pioneer spirit or as hapless provincial specimens in the vein of H.L. Mencken or Sinclair Lewis, but the integral force of the image was not in doubt. Wood himself preferred to describe it as a reflection on architectural style, informed by his study of Memling and other masters of the Northern Renaissance, and repeatedly denied any satiric intent—“I admire the people in that painting”—while conceding “the fanaticism and false taste of the characters in American Gothic.” As so often, his comments seem more an evasive cover story than a revelation.

It is a painting to which, in the words of the magisterial essayist Guy Davenport (who, for the record, considered Wood “the subtlest of American painters”), “we are blinded by familiarity and parody.” Yet to see it up close is to grasp how much it insists on being interpreted—the accents are too precise in every choice and rendering of detail for there to be anything casual about it. No accidents here. Davenport’s 1978 lecture “The Geography of the Imagination,” for instance, culminates in a dense four-page description of American Gothic that manages, in taking inventory of the picture’s elements (lathe-turned post, sash window, sunscreen, brooch, buttonhole, pinafore, pitchfork), to touch on everything from the invention of eyeglasses in the thirteenth century to the mythic significance of Poseidon’s trident, until the painting is made to seem a fantastically rich distillation of subterranean traditions.1 In another mode, R. Tripp Evans, whose biography of Wood focuses on his conflicted sexual identity, weaves a complicated narrative of incestuous desire and repressed resentments around the painting, in which each detail, such as the loose tress dangling from the woman’s otherwise tight coiffure, has a part to play: “If the figure’s unraveling hair marks her as a victim…it also suggests her potential as a predator.”2

Advertisement

But where in his art is that heartland for which Grant Wood was said to be the creative conduit, the native region that inspired him to assert that “a true art expression must grow up from the soil itself”? The deeper one advances into the Whitney show, the more it seems a soil of his own concoction, a heartland conjured in the mind of a boy growing up on an isolated farm, under the aloof and often harsh tutelage of a religious-minded father who forbade fairy tales or any other form of fiction in the house (“We Quakers read only true things”) and who, after physically chastising young Grant for one infraction or another, would subject him to readings from Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. In an unfinished autobiography Wood wrote of his father’s “stern, haunting loneliness” and “mystic aloofness.”

His sudden death when Wood was ten precipitated a move from farm to city as the family settled in Cedar Rapids. It was here, liberated from his father’s strictures, that he became free to follow his bent toward art-making in any available medium, going on to study in Minneapolis and Chicago and then Paris, mastering a multitude of crafts and turning himself into a creditable if not especially individualized painter in the Impressionist mode. He worked constantly but without clear direction until the breakthrough that brought him to the recognizable hard-edged portraiture of American Gothic and other works of the same period.

Whatever one makes of his art, it is clear enough that he lived for it. His existence otherwise seems to have been set in grooves from which he could not easily get free. Potentially liberating journeys to France and later to Germany, where by his own account he absorbed the crucial influence of those Northern Renaissance masters, always led him back to Cedar Rapids and the well-established social habits that seem to have camouflaged any contrary impulses. He lived with his mother until her death in 1935; for many years the two of them, on beds laid side by side, shared a sleeping alcove (often shared by sister Nan as well) in a loft loaned to Wood by a friend who ran a local funeral home, a space of less than nine hundred square feet that also served as Wood’s studio and as a salon where friends, colleagues, and inquisitive strangers often congregated.

Wood’s busy and crowded schedule of activities—fueled by an extravagant consumption of coffee, cigarettes, and, eventually, whiskey—did not lend itself to any publicly perceptible love life. Newspapers described him as a cherubic bachelor, almost childishly inept in the management of practical affairs. A 1930 newspaper column by his friend MacKinlay Kantor went so far as to suggest that Wood was “perhaps…most nearly in character one night when he appeared at a costume party dressed as an angel—wings, pink flannel nightie, pink toes and even a halo.” Wood’s sexual orientation doesn’t seem to have been in doubt to those who knew him well, and his art revealed a clear division between robustly handsome male farmhands and older, sometimes caricaturally unattractive females. The absence of outward scandal and the discretion of another era protected him from attack, even as his ostensible regionalist comrade-in-arms Thomas Hart Benton was publishing overheated polemics against the dire artistic influence of the mincing inverts of Paris and New York.

All the same, Wood’s private life has remained private, and he has often been described as repressed and closeted. Kantor later claimed, reporting Wood’s confidences in a long drunken conversation, that “virility in the sexual sense he did not admit or practice.” Any light his correspondence might have shed was foreclosed when his sister chose to burn it after his death. In his public pronouncements Wood was always careful to emphasize that his life held no secrets at all: “I’m the plainest kind of fellow you can find. There isn’t a single thing I’ve done, or experienced, that’s been even the least bit exciting.”

In a self-portrait first painted, to his own dissatisfaction, in 1932, and subsequently reworked by him but never finished, Wood as subject appears to react suspiciously to his own appraising gaze, and his lips are set as if through long habit holding back some bitter retort. The weathervane over his left shoulder might suggest his precarious vulnerability to prevailing blasts. That is as plain as it gets in his work, which otherwise thrives on feints and theatrical illusions. There was nothing impromptu or sketchlike about that work. As Evans points out in his biography, he increasingly devoted months to planning his compositions and perfecting his applications, almost to the point of concealing any trace of the painterly, intent on a glazed and planed surface that might have been produced by some unknown mechanical process. In matters of material realism Wood was painstaking, studying tools and garments and furnishings, the feathers of chickens and the patterns of furrows, shaping clay models to approximate the contours of landscapes, as if aiming at the most unimpeachable possible record of his observations, to produce in the end paintings notable for the flagrant unreality of their effect.

The obsessiveness of the process is visible in the hermetic airlessness of the results, the quality that Haskell describes as “a cold artificiality…as though Wood’s intense yearning to reconstitute what he called the ‘dream-power’ of childhood could yield only images of chilling make-believe, a dollhouse world of estrangement and solitude.” The chilliness, though, may be a matter of perspective. For Wood the toy houses past which, in The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, Revere gallops on what looks like a miniature rocking horse, along roller coaster roads in a settlement surrounded by fairy-tale woodland, or the farm folk of Dinner for Threshers inhabiting a paper cut-out of a model farmhouse, may have represented the comforting heart of a shoebox theater entirely under his control. Even the painstakingly realistic Appraisal, in which a countrywoman holds a rooster to be examined by an older and fashionably attired townswoman, becomes uncanny through the tableau vivant quality of the women’s ambivalent exchange of glances—a rare instance in Wood’s work of two people actually interacting. The more unreal he gets, the more he seems to approach his real heartland, which has less to do with the soil of Iowa or any other place than with the tangible materials of art-making. If he took months to finish a painting, perhaps it was to prolong the pleasure of the physical process and to forestall the question of how to begin again.

Although the region of Wood’s regionalism is a narrow one, nearly claustrophobic, drawing on images of a past already imaginary, he did for a time find a way to work it into a spaciousness of his own invention, a transfigured and pervasively sexualized landscape embodied in dream trees, dream fields, dream corn, dream ribbons of roadway or water—landscapes having only the most tenuous relationship to the actual and certainly no hint of actual dirt or dust. They have light but no weather. One cannot imagine wind blowing there. Seen from a slightly elevated angle, they are designed to induce a vertigo inviting a plunge into the core of that suspended undulation. With colors heightened—the yellows are of a brightness rarely seen outside Betty Grable’s Technicolor musicals of the late 1940s—and spatial relations bending like molten glass, the elements of the natural world take on the sheen of freshly fabricated playthings.

Paintings of this sort—Stone City, Fall Plowing, Young Corn, Near Sundown—have attracted considerable derision, early and late. Lewis Mumford in 1935 remarked, “If this is what the vegetation of Iowa is like, the farmers ought to be able to sell their corn for chewing gum and automobile tires.” In 1983 Hilton Kramer compared them to “immaculate marzipan,” and Peter Schjeldahl in a review of the current Whitney show has suggested them as appropriate backdrops for Warner Bros. cartoon characters. They certainly cannot be mistaken for natural views, but they radiate more joy than anything else Wood created: an inkling of a polymorphous Eden, its plant life that of another planet. The strangest of all is The Birthplace of Herbert Hoover, intended for some local Republicans who reneged on their commission when they got a look at it, and small wonder. Its townscape, in which the president’s actual birthplace is overshadowed by a riot of other elements, appears to depict a peculiar alternate world, a habitat for elves rather than a national shrine.

Wood’s period of creative fecundity was brief, about six years from the first hard-edged portraits leading up to American Gothic to the personal debacle of 1935, a year in which both his life and his art-making began to hit obstacles: a disastrous and short-lived marriage, the death of his mother, a move to Iowa City that seems to have unsettled him by separating him from his habitual life, a much-heralded New York solo show that met with harsh criticism from writers as prestigious as Lincoln Kirstein and Mumford, and, the following year, the beginning of a simmering feud with a colleague at the University of Iowa (where Wood had been teaching since 1934) that threatened to put a spotlight on his personal life. He painted less and less (the uncharacteristic Death on the Ridge Road, a distorted high-angle view of an impending highway crash, looks like an omen), drank more, and then underwent one more crisis when his limited-edition lithograph Sultry Night, depicting a frontally nude farmhand cooling off with a bucket of water from a horse trough, was deemed pornographic by the US Postal Service. His defense of the work was that it was an image from childhood, and it has the effect of a covert glimpse from a distance, the unattainable object of the gaze unaware of being looked at. After the oil painting for which it was a sketch was rejected by a major exhibition, Wood, in what seems a sad and suicidal gesture, lopped off the nude figure, leaving a canvas depicting a water trough under a tree: a landscape of emptiness.

He died of pancreatic cancer at fifty, just as the “regional school” of which he was a standard-bearer was beginning increasingly to be seen as a creation of publicity, tainted with jingoistic nationalism and even a whiff of fascist ideology. By 1949 Life was hailing Jackson Pollock as possibly America’s greatest painter, and Wood was becoming something less than a footnote. In a 1946 cartoon symbolically mapping contemporary American art, Ad Reinhardt consigned Wood and his fellow regionalists to the cemetery, while Clement Greenberg described him as “among the notable vulgarizers of our period.” I don’t think, though, that he can be made to disappear, wherever one chooses to situate him in the imaginary pecking orders of the dead. He hangs on the way his late lithograph Shrine Quartet hangs on: an image of the faces of four men each wearing the fez and tie of their fraternal order, casting long shadows against a backdrop of fake pyramids, the whole effect indelibly odd, at once grotesque and poignant, not quite yielding up any message beyond the precision of its own intent.