After six years in which he never traveled outside his country, never met with a foreign head of state, and maintained relations ranging from frosty to terrible with South Korea, China, and the United States, Kim Jong-un opened up to all three of those countries over three stunning weeks in March. He established a direct line of communication with the South for the first time in eleven years, scheduled an April meeting with South Korean president Moon Jae-in, invited President Trump to a summit meeting currently planned for May, and then traveled secretly to China for meetings with Chinese president Xi Jinping.

In all likelihood, Kim has emerged from his seclusion because of the rapid advance of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. In 2017 twenty missile tests followed one another in quick succession. During the year North Korea demonstrated that it had both mobile and solid-fuel missiles. (The latter can be readied for launch much more quickly than liquid-fuel models and are therefore harder to target and destroy.) The climax came in the fall. On September 3, North Korea tested a weapon that US experts have concluded was a hydrogen bomb. Two months later, on November 28, it successfully launched a new intercontinental ballistic missile with a range of 8,100 miles, and thus able to reach anywhere in the United States. North Korea has not yet shown that it can build a missile warhead capable of surviving the stresses of atmospheric reentry, but that appears to be its only remaining technological hurdle.

In addition to an unknown number of nuclear weapons, North Korea has an arsenal of chemical weapons and at least some of the advanced equipment needed to produce biological weapons. The discovery of antibodies to anthrax and smallpox in the blood of North Korean defectors indicates that the country has produced these two agents. It has possibly worked with cholera and plague as well. Satellite photographs taken in January and February suggest that a nuclear reactor may now be producing plutonium. Kim may be balancing diplomacy with a not-so-subtle reminder of his commitment to nuclear weapons, or adding a bargaining chip to his pile.

As Trump and Kim exchanged schoolyard taunts over the past year, few could have predicted that Kim would suddenly switch from testing bombs and missiles to launching a diplomatic initiative. It began with his annual New Year’s Day address, in which he announced that North Korea had achieved “national nuclear power” and that he hoped to send athletes to participate in the Winter Olympics in South Korea. His grandfather, by contrast, before South Korea hosted the Summer Olympics in 1988, blew up a Korean Airlines flight, killing everyone on board, in an attempt to scare participants away from the games. President Moon, who has fervently advocated a “sunshine policy” of engagement and cooperation with the North for more than fifteen years, jumped on Kim’s offer. The two teams marched together in the opening ceremonies, and Kim—again for the first time—sent a high official (his sister) to sit in Moon’s box. He did not react when US Vice President Mike Pence rudely shunned her.

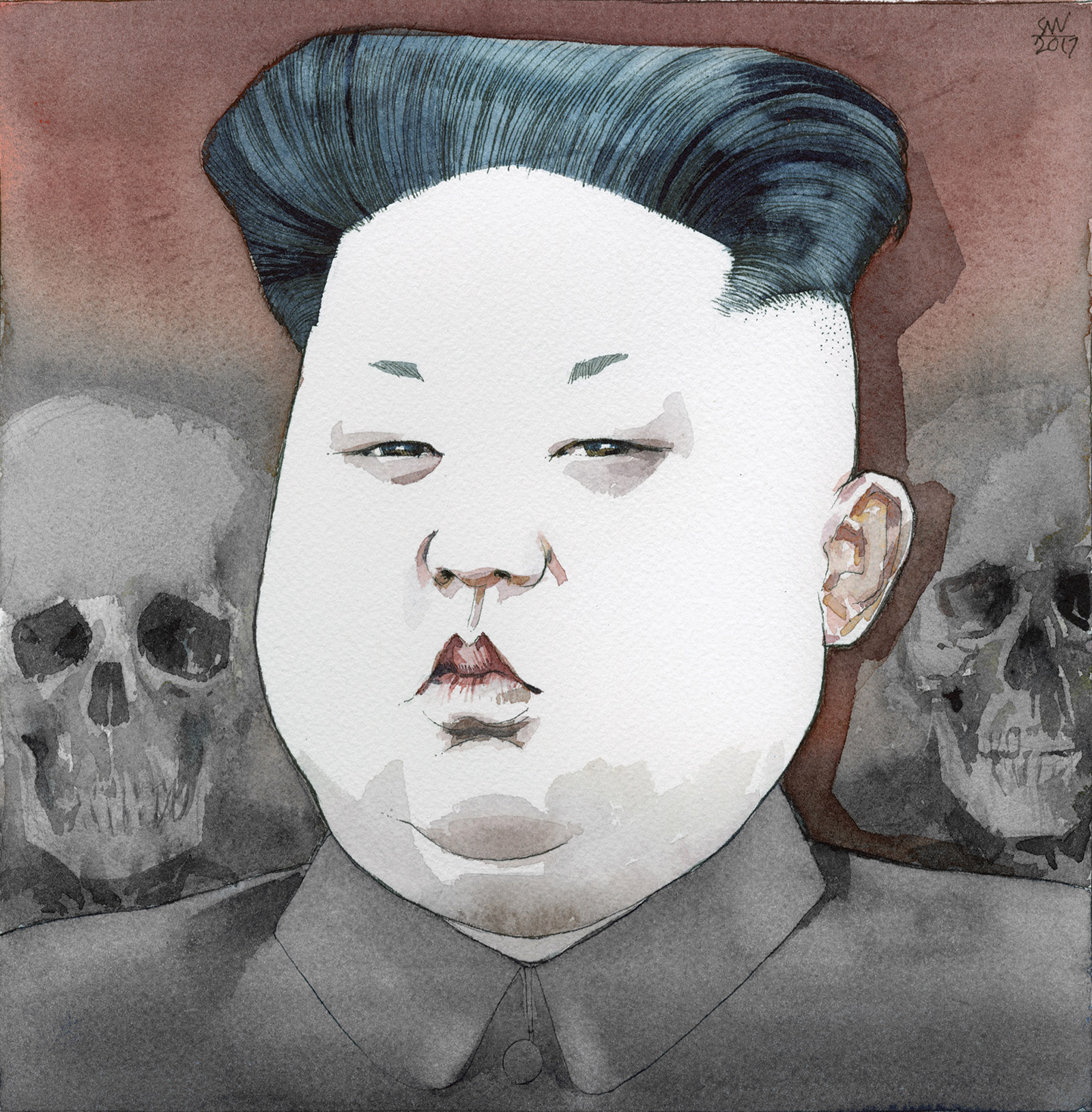

This is not to say that Kim has suddenly become soft or predictable. Even elementary facts, like the ages and genders of his children, are uncertain, not to mention his policy priorities, political standing, the military capabilities at his command, and especially his long-term goals. He has shown himself to be ruthless and cruel but also far more capable of consolidating power than the US first believed. He ordered the assassination of officials loyal to his father, Kim Jong-il (including at least five of the seven men who had carried his coffin), and replaced them with cadres loyal to himself. He makes a show of particularly brutal killings; at the same time, he has made gestures toward modernization by building amusement parks and allowing some free markets to operate. He has also removed some of the aura of mystery that surrounded his predecessors by speaking more often in public. Yet he continues to spend scarce resources on propaganda to ensure that North Koreans continue to think of Americans as vicious killers. He emphasizes North Korea’s need for economic growth, but has prioritized nuclear and missile programs over economic ones.

Until last month the only foreigners Kim was known to have had significant contact with while in office were a Japanese chef and the American basketball player Dennis Rodman. In short, he is decidedly strange, but considerably more able than he seemed at first, and neither crazy nor suicidal. The third ruler in a family dynasty that has put regime survival above all else, he is a young man in his mid-thirties with the prospect of decades in power to look forward to.

Trump’s motives are almost as puzzling as Kim’s. North Korea has tried for decades to meet with a sitting president of the United States to boost its international standing. When Kim proposed a summit, Trump brushed aside his aides’ concerns and leapt to accept the vague oral invitation, conveyed to him secondhand by a South Korean official, without first pinning down the precise meaning or seriousness of any of Kim’s promises. Then, by taking at face value Kim’s statement that he is “committed to denuclearization,” Trump allowed what has heretofore been a US precondition for negotiation to become its goal. Together these two decisions amount to a significant softening of previous US demands on Pyongyang, with nothing received in return. They were the kind of decisions candidate Trump would have blasted unmercifully, but they could be good ones nonetheless, if the president is in fact prepared to negotiate.

Advertisement

Only days after taking this major step, however, Trump fired Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who had tried for months to start negotiations with North Korea. In October, Trump had tweeted that Tillerson was “wasting his time trying to negotiate with Little Rocket Man.” (“Save your energy, Rex, we’ll do what has to be done!”) To replace him, he nominated CIA Director Mike Pompeo, who has insisted that he does not necessarily support regime change in North Korea, but who has used language that could mean little else. “The most important thing we can do,” he said at the Aspen Security Forum last summer, is “separate [nuclear] capacity, and someone who might well have intent…. I am hopeful we will find a way to separate that regime from this system…. The North Korean people, I’m sure are lovely people and would love to see him go.”

Trump then fired National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster and announced that he would replace him with former UN ambassador John Bolton, who has repeatedly urged the US to bomb North Korea without provocation. “It is perfectly legitimate for the United States to respond to the current ‘necessity’ posed by North Korea’s nuclear weapons,” Bolton wrote in February, “by striking first.” This is an argument for preventive war—not for preemption, but for a war undertaken in the absence of imminent threat, a concept that has no legitimacy under international law and has been rejected by US presidents from Lincoln to Eisenhower, Truman, and Kennedy.1 Preventive war was used by George W. Bush to justify the invasion of Iraq, a monumental blunder that Bolton still vigorously defends.

Both new appointees share Trump’s belligerence and both, in contrast to their predecessors, are fierce opponents of the Iran nuclear deal. It therefore seems all but certain that Trump will follow his desire to pull out of that agreement on May 12, the next deadline when he is required to extend the waiver of sanctions on Iran. If he chooses to breach the deal in some fashion or pulls the US entirely out of it, he will undermine his chances of reaching a deal in Korea. The North Koreans would have to conclude, going into the summit, that the United States cannot be trusted to abide by even its most carefully negotiated commitments.

At least initially, the Trump administration believed that its “maximum pressure” policy, including threats of “fire and fury” and tightened sanctions, had cowed North Korea and that the president would be meeting a weakened Kim. This is almost certainly wrong, and dangerously so. The sanctions have undoubtedly hurt North Korea, but this is a regime that has endured much worse. During the devastating famine of the 1990s, the regime let more people die rather than bend to international conditions for food aid.

Threats are also unlikely to be effective. Loose warnings of military action only reinforce North Koreans’ paranoid belief that America is an existential threat. More rationally, they realize that the US doesn’t know the location of all of their WMDs and that therefore a first strike is unlikely because it could not succeed in eliminating all of them.

Nonetheless, Trump’s team has actively considered a so-called bloody-nose strike that planners think would demonstrate the United States’ resolve but manage to avoid escalation to a catastrophic war. Victor Cha, Trump’s choice for US ambassador to South Korea and a hard-liner on North Korea, felt strongly enough about the folly of these plans to withdraw from consideration and publish a direct attack on the thinking behind them:

If we believe that Kim is undeterrable without such a strike, how can we also believe that a strike will deter him from responding in kind? And if Kim is unpredictable, impulsive and bordering on irrational, how can we control the escalation ladder, which is premised on an adversary’s rational understanding of signals and deterrence?2

Bloody nose or all-out war, the Pentagon had never found a promising plan for attacking North Korea even before it had nuclear weapons, since the North has thousands of protected artillery pieces within striking distance of Seoul, which is only thirty-five miles from the border. Pyongyang’s imperviousness to threats, its willingness to suffer the bite of extreme sanctions, and its enormous recent technological progress suggest that it is Kim rather than Trump who would arrive at a meeting believing that he occupies the position of greater strength.

Advertisement

In these strange conditions it is uncertain at best whether a Trump–Kim meeting will actually take place. If one does, the central issue will be the huge discrepancy between what the US and the North Koreans mean by the phrase “committed to denuclearization.” Explaining his readiness to accept the North Korean invitation, Trump shouted to reporters, “They’ve promised…to de-nuke.” They have not. To most Americans and perhaps to Trump, in view of his allergy to briefings, “committed to denuclearization” sounds as though North Korea is prepared to give up its nuclear weapons. But what North Korea has meant by this phrase in the past is that it will only give up its nuclear program after the US military withdraws from South Korea (or possibly from all of Northeast Asia) and after America’s nuclear umbrella no longer shelters the South from attack.

If the US were to abandon its alliance with South Korea and Japan in this way—that is, before achieving peace on the Korean peninsula—its word would mean little anywhere in the world. Alliances would erode, and there would be fewer countries willing to vote with us, impose sanctions with us, fight with us, or host US military bases. North Korea has also sometimes used “denuclearization” to mean that, as one of nine nuclear states, it will denuclearize when the other eight do. If such global nuclear disarmament ever does happen, it lies many decades—and several geopolitical miracles—away.

In the weeks since Trump agreed to the meeting, it has become clear that Kim meant what he has meant in the past. He has enlisted both Beijing and Seoul in support of what he called “phased, synchronized” denuclearization, meaning that Pyongyang would demand that the US take steps that are, or should be, unacceptable to us, before it would cut back its nuclear program. After meetings with envoys from Beijing, a senior South Korean official said that after the decades of effort North Korea invested in its nuclear program, it could not be ended “like you turn off your TV by pulling out the electricity cord.” Trump and Bolton, however, still favor what they call “the Libyan option”—quick and total dismantling. The term could not be more ill-chosen. Kim is well aware of the grisly end Qaddafi suffered after giving up his nuclear program, and he has no intention of following suit.

If this crucial difference does not derail the meeting before it happens, what might be negotiated? Expectations should be low. The US has little time to prepare. The relevant government agencies are badly understaffed and in the midst of chaotic leadership changes. The president will not study briefing papers and there is no interagency process to work out a negotiating strategy. North Korean officials, on the other hand, will be minutely prepared and buttressed by the results of two prior summit meetings. Washington knows what Pyongyang wants: diplomatic recognition; a formal end to the Korean War (which was halted by an armistice that is still in effect) through a peace treaty with the US; legitimization of its nuclear status; sanctions relief and, perhaps, economic assistance. What the US should demand in exchange, and what Pyongyang is willing to give, is much less clear.

On two points, there should be no room for concession. First, Washington must not allow daylight between itself and its South Korean and Japanese allies. It cannot afford to take an “America First” line that concentrates on the new risks it faces from North Korea’s ICBMs and disregards the long-standing risk to South Korea and Japan from shorter-range weapons. Second, given North Korea’s history of breaking international agreements, whatever is negotiated must be rigorously verifiable. That may seem obvious, but for North Korea it is a major hurdle that drastically narrows what can be attempted. Verification requires as a first step that Pyongyang make a full and honest declaration of all its current weapons, weapons fuel, and weapons-related facilities. The declaration would then have to be minutely confirmed by inspectors who could travel freely throughout the most secretive country in the world, leaving behind intrusive monitoring equipment.

There would need to be clear and automatic consequences for violating these requirements. Former defense secretary William J. Perry, who has years of experience with arms control, including a failed effort in Pyongyang twenty years ago, believes that the very modest goal of a ban on further nuclear and missile tests and on the export of nuclear technology is all that can be hoped for.3 He argues that it would be impossible to verify even a freeze in the number of existing warheads, much less cuts. There is a stunning contrast between the modest goals that might be realistically achievable in North Korea and the stringent cuts and verification measures already in place and working under the Iran deal.

North Korea will never rely on the word of the US alone, so any agreement would require the support of China as well as South Korea, Japan, and probably Russia. China is the most important of these in both the short and long term, which is why it was a masterstroke for Kim to travel to Beijing and defer ostentatiously to Xi while there. The visit did no more than ease the deep distrust between the two official allies, but it made sure that Beijing did not feel excluded from North Korea’s diplomatic outreach and substantially strengthened Kim’s position. In a matter of weeks, this once reclusive, seemingly inept leader has made his country the center around which three vastly more powerful nations are maneuvering.

For Pyongyang to remain under pressure, China has to keep supporting tough sanctions, but Beijing will not bring North Korea to the point of collapse. It fears the uncontrolled access to nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons that could follow the fall of North Korea’s government, as well as a likely flood of refugees. China also believes that a successor state would be dominated by South Korea, putting a close ally of the US—possibly with nuclear weapons and with US forces still in place—on its own border. Washington and Beijing have never attempted to discuss whether there is a long-term vision of a united Korea that would be acceptable to both of them. It is unlikely that the Trump administration would or could attempt such a strategic discussion, and current tensions in Sino-US relations make this an unpropitious time to try, but it must happen eventually.

The chances of a successful Trump–Kim summit seem slim. Two members of President Trump’s new national security team favor force over diplomacy. Secretary of Defense James Mattis is outnumbered, although, unlike the pope, he has the troops. The president believes too much in the efficacy of bluster and threat, and he has shown no willingness to do the hard preparatory work that international negotiations require. If the summit does take place, the greatest danger would come from an acrimonious failure. Summit meetings generally follow lower-level negotiations for the good reason that if talks fail at the top there may be no paths left open for diplomacy, and force becomes the only option. This, above all, is the reason that both parties should set a low bar for what they would consider success.

It could prove useful, however, for President Trump to experience firsthand how much more difficult it is to build an international agreement than it is to criticize or break one. As he and his team confront what might be negotiable with North Korea, they should find it harder to dismiss the much more drastic limits and verification terms that have been imposed on Iran. They might notice the irrationality of reigniting one nuclear weapons crisis while at the same time trying to reduce the threat of another. And perhaps they may come to see a more fundamental truth: that neither limited bombing nor full-scale war would end nuclear proliferation in either Iran or North Korea so much as make it permanent. If attacked by the US, neither country would ever feel safe again without nuclear weapons. Diplomacy is agonizingly slow, frustrating, and generally productive of less than perfect results. The trick is to know when every other option is worse.

—April 10, 2018

-

1

See Arthur Schlesinger Jr., “Eyeless in Iraq,” The New York Review, October 23, 2003. ↩

-

2

Victor Cha, “Giving North Korea a ‘Bloody Nose’ Carries a Huge Risk to Americans,” The Washington Post, January 30, 2018. ↩

-

3

William J. Perry, “What Trump Could Learn from My Attempts to Denuclearize North Korea,” The Washington Post, March 12, 2018. ↩