On a cold winter day in 1989, Julius Eastman huddled in a group of homeless men outside Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan, warming his hands by an oil-drum fire, when a reporter from Newsday approached him. The day before, a young female doctor, five months pregnant, had been raped and murdered inside the hospital. Eastman, who said he played piano at the men’s shelter across the street, surprised the reporter by speaking about the case “with greater intelligence than anyone in a Giorgio Armani suit.” The reporter wondered “how such an articulate fellow wound up warming his piano player’s fingers over a street fire, waiting for the shelter to open.” “That’s too long of a story,” Eastman replied. “I’m 48. I’ll get it back together.”

He never did. A year later, Eastman died of heart failure in a hospital in Buffalo, where he’d first made a name for himself as a composer. Kyle Gann published a moving obituary eight months later in The Village Voice, but his passing was otherwise unremarked. A prominent figure on the experimental music scene throughout the 1970s, he ended his life an invisible man, his name all but erased from musical history, as if his short, dazzling career and his fiercely original art had been a collective hallucination.

Eastman’s disappearance was no small achievement, for it was hard to imagine a more visible figure: his aim was not merely to make himself heard but to make himself seen. A pianist, singer, and composer, Eastman was both black and gay, and proclaimed his identities in brazenly titled compositions such as Crazy Nigger, Gay Guerrilla, and Nigger Faggot. “What I am trying to achieve,” he said, “is to be what I am to the fullest: Black to the fullest, a musician to the fullest, a homosexual to the fullest.”

Wiry and graceful, with some of the only dreadlocks to be found in the very white world of new music, he commanded attention by his presence alone, but he was also a musician of extraordinary gifts to whom success came early. In 1966, he gave his first solo piano recital at Town Hall and sang in Der Rosenkavalier with the Philadelphia Orchestra. By 1970 he was an underground hero, thanks to his electrifying performance as King George III in Peter Maxwell Davies’s music theater piece Eight Songs for a Mad King. Imposing in his royal brocaded gown and furred cap, he created an astonishing impression of delirium, using his five-octave range to produce a clamor of squawks, cackles, roars, and cries. Eastman toured the piece throughout Europe and was nominated for a Grammy for the recording.

As a composer, Eastman gravitated to the movement known as minimalism, but while his music shared some of the features typical of minimalism (a steady pulse, repetitive structures), it bristled with dissonances and improvisation, neither of which could be heard in the tonal, fastidiously structured early compositions of Steve Reich and Philip Glass. Eastman was among the first minimalists to dispense with the movement’s ascetic preoccupation with “process” in favor of expressive fireworks and a visceral, even messy grandiosity, qualities that prefigured the “post-minimalist” work of composers like John Adams. Playing his music, he felt “as if I am trying to see myself—it’s like diving into the earth.”

By the early 1980s, Eastman was smoking crack and sleeping in Tompkins Square Park. When he showed up at concerts, it was to ask his friends for loans. He lost nearly all his scores, and appeared to show as little concern for his musical legacy as he did for his health. Wandering the streets in flowing garments and a turban, he looked like another sad-eyed prophet of the Lower East Side. He told his friend Ned Sublette, a composer and author, that the music he had made reflected an “inconsistent period,” best forgotten, and it nearly was. When Eastman died, only a few recordings of his powerful singing were available, and none of his compositions.

As it turned out, there were Eastman recordings, some stored in university libraries, others hidden away in private collections. The composer Mary Jane Leach, an Eastman acquaintance and fan, spent a decade tracking them down, and in 2005 released a revelatory compilation, Unjust Malaise. (The title is an anagram of his name, created by the composer David Borden.) Thanks in large part to Leach’s archival work, Eastman is now lionized in the art world and academia as a visionary practitioner of “intersectionality,” a queer black saint like James Baldwin.

Two more archival recordings have recently surfaced: Femenine, an extended, incantatory work from 1974 for chamber ensemble and a motorized sleigh bell; and The Zürich Concert, an improvised piano recital from 1980. Last winter in New York City, the Kitchen, where Eastman often performed, held a three-week retrospective that attracted an audience of a kind seldom seen at classical music concerts: young, stylish, and racially mixed. The performance of Eastman’s late, gothic pieces for four pianos felt like a séance: hundreds of young hipsters sat on the floor, listening in rapt silence as the room was filled with a somber wash of overtones.

Advertisement

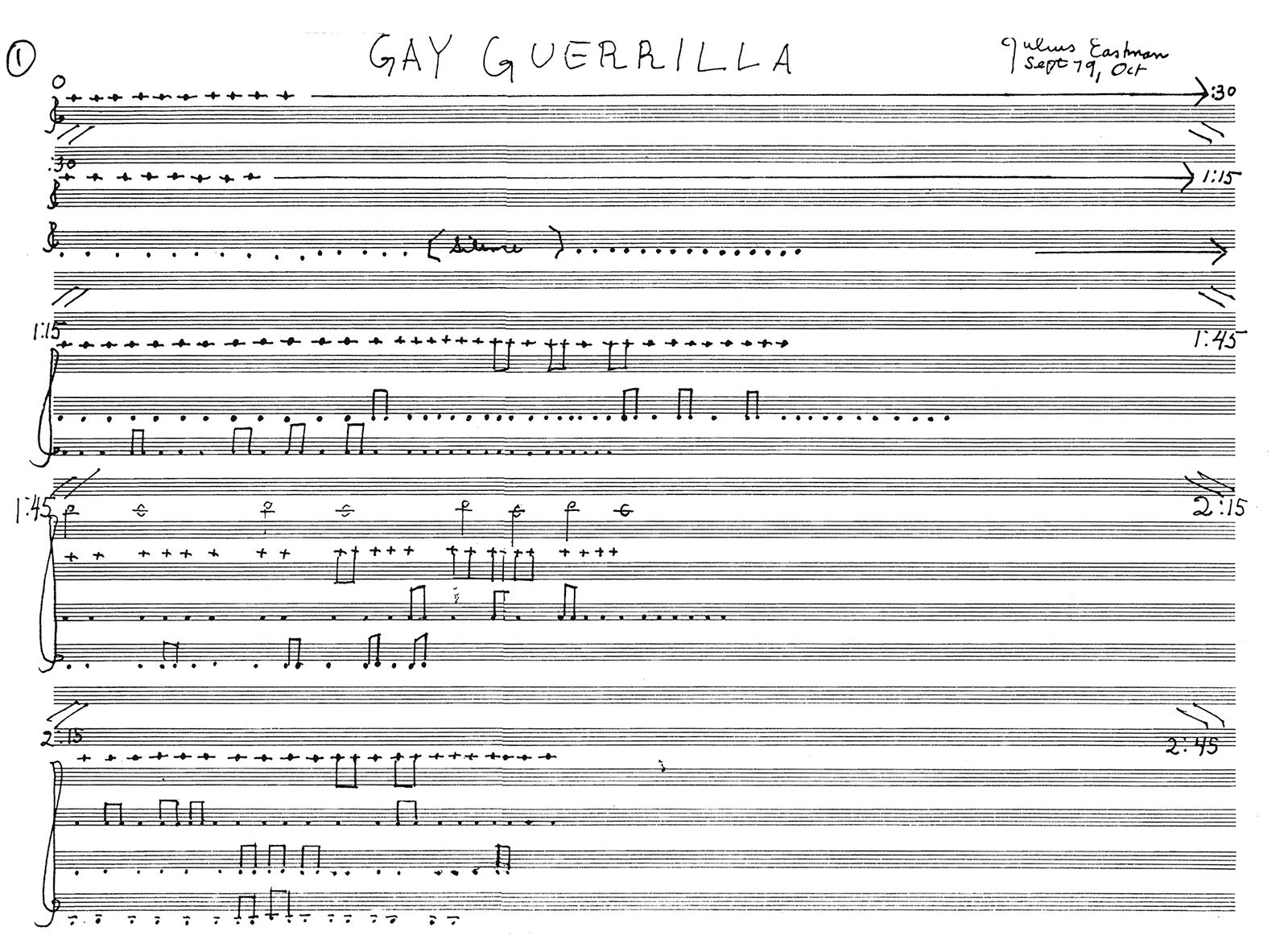

A number of the pieces performed were based on guesswork by musicians who had reconstructed Eastman’s fragmentary scores. Eastman, who never had a publisher in his lifetime, fleshed out the details of his pieces in rehearsals, and his surviving scores (he composed roughly fifty-eight works) are more like jazz charts than classically notated compositions. Only through a comparison with recordings (such as they are) can his intentions be fully discerned. As Matthew Mendez observes in Gay Guerrilla, a volume of essays on Eastman’s work, “the Eastman situation is rather more akin to what early music scholars regularly face than to any twentieth-century precedents.” This difficulty has not discouraged the music publisher G. Schirmer, which just signed a deal with the Eastman family estate. Eastman, who rebelled against every kind of convention, is entering the classical music repertoire he dreaded.

He was born Julius Dunbar Eastman Jr. in 1940 in New York City, but soon moved to Ithaca, where his mother, Frances Famous, a strong-willed woman of Trinidadian descent who worked as a clerk in a hospital, raised him and his younger brother, Gerry, in a largely black neighborhood. A “strange” child (in his mother’s words) and a musical prodigy, he became a paid chorister at an Episcopalian church and took piano lessons with Seymour Lipkin, Leonard Bernstein’s assistant conductor. After a year at Ithaca College, he transferred to the Curtis Institute of Music; he studied piano and composition as well as choreography. (A baritone of tremendous range and lacerating yet poised intensity, Eastman never actually studied voice.) His goal at Curtis, where he was one of only two black students in a class of a hundred, was to “obtain wisdom,” but he hated the school, and said that if he had “to live there another year I shall die a morbid death.” Still, the Curtis training never left Eastman, who often complained of the lack of rigor in the New York downtown scene.

In 1969, Eastman joined the Creative Associates, a pioneering new music collective at the State University at Buffalo, at the invitation of its director, the composer and conductor Lukas Foss. “There was something quietly grave about Julius,” Renée Levine Packer, who worked as a coordinator for the Creative Associates, told me. “He was very elegant, and he moved beautifully.”

In his early compositions, Eastman gave free rein to his exuberant, theatrical, often mischievous imagination, and demonstrated a flair for creating captivating music on the basis of the sparest of directions. The “score” of his 1972 vocal quartet, Macle, was a diagram of lines, shapes, and instructions (make “very nasty sounds,” for example), scribbled on four boxes, one for each singer, in the manner of one of John Cage’s chance pieces. The conversation that ensues is a half-hour suite of gurgles, screams, laughter, hiccups, whispers, and occasional singing (sing “your favorite pop tune” is another instruction). The only connective thread is the mantra “take heart,” yet the work holds together, like one of Beckett’s late plays.

Eastman’s breakthrough came a year later, with Stay On It, a twenty-four-minute composition for voice, piano, mallet percussion, two saxophones, clarinet, and violin. It opens with a staccato pop riff, over which a woman sings the title. Halfway through, the rhythmic order breaks down in a riotous free-jazz medley. A slinky, bittersweet melody takes shape, first tentatively, then with growing force, only to give way to languorous piano chords, accompanied by subtle accents on the tambourine. Stay On It is a work of such contagious charm that one could easily overlook its audacity. While it draws on the repetitive grooves of minimalism, its feeling for time is much looser. Eastman preferred to speak of “the beat” rather than “the pulse,” the term favored by minimalist composers, and looked upon their borrowings from non-Western rhythms with bemusement; he wrote a parody of a composer, clearly based on Reich, who visits an African village and writes down “the various rhythms and melodies, unbeknownst to the natives.” Rather than look to the ritual music of Africa and the East, Eastman found his rhythms on the dance floor, which gave his music an eroticism far removed from the cool, trance-like states of minimalism. A cellist who performed in Stay On It said that playing it was like “musical lovemaking.”

Not everyone appreciated Eastman’s eroticism. In 1975, John Cage watched in horror as Eastman performed a section of Cage’s Song Books at a festival in Buffalo. Cage’s piece included the direction “give a lecture.” Eastman lectured on “how to make love” to a young man (his lover) and a young woman, and proceeded to undress the young man (the woman resisted). In effect, Eastman undressed Cage, a gay man of immaculate discretion, outing the furtive eroticism of his art. “The ego of Julius Eastman is closed in on homosexuality,” Cage fumed. “The freedom in my music does not mean the freedom to be irresponsible!”

Advertisement

By then, Eastman had become embittered with the new music scene. His difficulties were partly of his own making. He lost his job teaching at SUNY-Buffalo because he stopped showing up for class, and turned down an offer from Pierre Boulez to perform Eight Songs for a Mad King with the New York Philharmonic, since he hated to repeat himself and was unmoved by financial considerations. (“Look, I like money,” he said, “it’s a nice invention, but it doesn’t turn me on enough for me to do something just for that.”) As one of the few blacks in Buffalo new music, he also felt like “a kind of talented freak who occasionally injected some vitality into the programming.”

His alienation intensified after the 1971 Attica Rebellion, which took place only thirty miles from Buffalo. Eastman performed as the narrator of Frederic Rzewski’s powerful Attica homage, Coming Together, a work of left-wing minimalism that would strongly influence Eastman’s later writing. Attica, and the rise of black power, also led Eastman to draw closer to his brother, Gerry, a bassist and guitarist in the Count Basie Orchestra, and to other black musicians. As he put it at the time, “I came to jazz because I feel it comes closer than classical music to being pure, instantaneous thought.”

Some of Eastman’s white friends were skeptical of his rhetorical embrace of jazz, and considered it a disingenuous concession to black musicians who had criticized him for playing with whites. “He did not come out of the blues,” the flutist and composer Petr Kotik insists. “He practiced Mozart!” Yet Eastman had grown irritated with the whiteness of new music and with the other hierarchies he felt it reinforced, such as the distinction between composer and instrumentalist. “To be only a composer is not enough,” he wrote in an essay, lamenting that there had been a “splitting of the egg into two parts, one part instrumentalist, one composer,” and that the composer had “become totally isolated and self-absorbed.”

Partly to escape this isolation, but also to escape Buffalo, which had become too small for his ambitions, Eastman moved to New York in 1976. The downtown avant-garde was exploding, and he soon found himself in demand and among like-minded composer-instrumentalists seeking to fuse notated music, improvisation, and transgressive politics. He sang in Meredith Monk’s otherworldly oratorio Dolmen Music, played keyboards in an avant-garde disco band led by the electric cellist Arthur Russell, and had a starring role in Inside the Nuclear Power Station, a futuristic opera by Peter Gordon with a libretto by the punk-feminist writer Kathy Acker.

He also developed his practice as a soloist, giving hour-long recitals of entirely improvised piano music. He played with bare feet, because he had better control of the pedals without shoes, but also because he liked direct physical contact with them. Mary Jane Leach, who wrote the liner notes to The Zürich Concert, hears echoes of Cecil Taylor and McCoy Tyner in Eastman’s thunderous playing, but the language is closer to classical modernism, particularly the percussive fervor of Bartók and Stravinsky. Eastman pounds on the lower registers of the piano with his left hand while sustaining a rippling ostinato with his right, creating majestic waves of sound, which are followed by spare, atonal passages suggestive of Webern. Unrelenting in its force, it feels like an offering to the gods until, twenty-five minutes into the concert, Eastman breaks into song, pleading with a lover to “come naked alone,” but also, pointedly, to leave “your history” at the door. Possession, not seduction, is his aim. The new music disc jockey David Garland compared the experience to “being shouted at. There was an intensity of conviction both physically and psychologically that was harrowing…. It gave me a headache.”

Eastman, who often dressed in leather and chains, embraced the freedoms of post-Stonewall gay life. He pursued cruising as if it were a sacred activity, and was known as Mr. Mineshaft on the S/M scene. In an essay in Gay Guerrilla, R. Nemo Hill, his lover in the early 1980s, remembers participating with Eastman in an orgy at the urinals in the 125th Street subway station when the police appeared. Hill attempted to run off, but Eastman stopped him. “Wheeeere the hell do you think you’re going? Get back in here and face it like a man!” After being given a reprimand, they went for a drink, only to “return to the scene of the crime, where we resumed what had been interrupted, albeit with a different set of partners.”

In New York, Eastman’s compositional sensibility acquired an increasingly defiant edge, particularly in his “Nigger” and “Faggot” pieces, which he called his “bad boys.” Scored for multiple instruments and typically performed on four pianos, they have a throbbing energy like much of the minimalism of the period, but their harmonic density and dissonance are unusual. So is their explicit assertion of identity. If the price of acceptance by his white peers was being tight-lipped about his race and sexuality, and writing pieces with titles like Music for 18 Musicians or Music in Twelve Parts, Eastman chose titles that stated in no uncertain terms that he would not pay it.

Presenting the “Nigger” and “Faggot” works was no easy matter. During his residency at Northwestern University in 1980, a black student group, For Members Only, rose up in protest over the titles of his compositions. A compromise solution was reached: the titles would not be printed in the program notes, but Eastman would explain them on stage. Dressed in army fatigues and combat boots, he said:

What I mean by “niggers” is that thing which is fundamental, that person or thing that attains to a basicness, a fundamentalness, and eschews that thing which is superficial, or, what can we say, elegant…. There are of course ninety-nine names of Allah, and then there are fifty-two niggers.

Richard Pryor couldn’t have said it better. “Niggers” had nothing to be ashamed of. On the contrary, they had built “the American economic system,” and even wrested an improbable victory from the system that oppressed them: an authenticity, a more immediate connection to reality.

In Crazy Nigger, Eastman’s epic 1978 composition for four pianos (most commonly), the material is simple, even crude—a repeated, agitated B-flat is heard through much of the work—but it imposes extreme physical demands on the pianists, who are often required to pound on a single note for minutes at a time. It opens with a dark, restless rumbling of notes, producing increasingly thick, dissonant harmonies. Twenty minutes into the piece, a pentatonic figure repeats in all the pianos, lending warmer tonalities that offset the otherwise frenetic hammering. Eventually they reach a kind of clearing, as the music settles on a low C-sharp. In the last few minutes, we hear a cascade of notes, with glorious canon-like effects, as another group of pianists—more laborers, in effect—join the quartet. It is a gorgeous, almost transcendental sequence, but its power is achieved by underscoring the “basicness,” the manual labor, repetition, and sweat concealed by most art: to experience the beauty of Crazy Nigger, you first have to undergo an endurance test.

Gay Guerrilla, another “bad boy” performed at Northwestern, imposes similar demands. “If there is a cause, and if it is a great cause,” Eastman explained from the stage, “those who belong to that cause will sacrifice their blood, because without blood there is no cause. So therefore that is the reason that I use ‘gay guerrilla,’ in hopes that I might be one if called upon to be one.” The idea of gay martyrdom struck a powerful chord with Eastman, leading him back to the music of the church. The musicologist Luciano Chessa argues that Eastman melded homosexuality and Christianity into a “sincere, if queer religiosity.” Gay Guerrilla derives its form from the chorale fantasia and unfolds with an increasingly martial drive, as a series of notes is incessantly repeated and pitch is piled upon pitch, emitting a kind of tonal mist. Toward the end, the triumphal, ringing chords of Luther’s “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” arise out of the haze, transfigured into an anthem of gay liberation.

Eastman’s “bad boys” were examples of something he called “organic music,” in which every section of a piece has to “contain all the information of the previous section, or else, taking out information at a gradual and logical rate.” But what unified his late music was not so much its formal logic as its self-mythologizing spirituality. The Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc (1981), for example, was written as “a reminder to those who think that they can destroy liberators by acts of treachery, malice, and murder.” A twenty-minute suite for ten cellos, it has a violent swagger reminiscent of a punk rock anthem, and for good reason: its lunging rhythmic structure, a sequence of insistently repeated sixteenth notes, is lifted from Patti Smith’s “Rock N Roll Nigger.”

Even more striking than The Holy Presence is its solo vocal prelude. Eastman recorded it in his apartment on East 6th Street; only two pages of the original score survive. The lyrics invoke the saints Joan claimed to hear before her trial: “Saint Michael said/Saint Margaret said/Saint Catherine said/They said/He said/She said/Joan/Speak boldly/When they question you.” These are the only words Eastman sings, in a solemn plainchant, with improvised variations, over the prelude’s twelve-minute duration, and the musical material could hardly be simpler. But as Leach notes, “you do not notice how little is happening musically” because Eastman’s grand, stately baritone achieves such a riveting sense of musical drama. While the use of language suggests Gertrude Stein, the effect is quite the opposite: instead of draining the text of meaning, Eastman’s recitation amplifies its power, underscoring the gravity of Joan’s situation. We are left with a work of mesmerizing austerity from which everything has been stripped away except Eastman’s stark, unadorned voice, offering desperate words of solidarity to Joan in her final hours.

These were words Eastman himself needed to hear, for not long after The Holy Presence, his life began to fall apart. He had long depended on help from friends to cover his rent. But eventually his benefactors grew exasperated, and sometime in the early 1980s, the sheriffs removed Eastman from his apartment for nonpayment. He lost nearly all his belongings, including his scores and his master tapes. “I was almost in tears when Julius told me his life’s work was on the street,” Meredith Monk told me, but Eastman serenely accepted his new life as (in his words) a “wandering monk.” The efforts by Leach and others to recover Eastman’s work have only burnished his legend as a bohemian saint. R. Nemo Hill, who discovered the score of The Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc underneath a pile of dried cat shit in Eastman’s apartment, claims that “cat shit and eviction were, and always will be, as integral a part of that Holy Presence as the ten bows that dragged this divinely infernal music out of those ten growling and wailing cellos.”

Other friends of Eastman take a less romantic view of his disintegration. The pianist Anthony Coleman recoils at the idea that “all of Julius’s behavior came out of a state of grace. Part of him was driven, part of him was Buddha-like, and part of him was just self-destructive.” The last time Coleman saw Eastman, he was standing on the corner of Second Avenue, in white robes and a turban, holding a stack of scores. He said he was on his way to the East German consulate, because only East German orchestras were capable of playing the symphonies he was writing. No orchestral score has surfaced, but Eastman continued to compose, albeit using an opaque form of notation that all but required his input, whether or not they required the supreme interpretative skills of East German musicians.

One of his finest late pieces is a surprisingly traditional sonata, Piano 2 (1986), a work of bleak and smoldering beauty. Eastman never recorded it, and the score he left behind contains no dynamics or time signatures, and only one or two bar lines; each of the movements ends with a Japanese character and the word “Zen.” Fortunately, Eastman played the sonata for Joseph Kubera, a pianist he’d known in Buffalo, on an unannounced visit to Kubera’s home in Staten Island. Kubera has released a luminous account on his album Book of Horizons.

Why did Eastman fail to specify his intentions on the page? Some of his colleagues from Buffalo believe that he lacked the discipline required to compose. But this apparent failure was consistent with his belief that music was something to be created in the moment by composer-instrumentalists, and he had no interest in music as artifact. Imprecise notation may also have been his way of ensuring ownership of his work, since it was orphaned without him. “Julius wanted to assert his presence,” Ned Sublette says. “His work was about the affirmation of his existence, and that is precisely what he undid in his life.”

Fragile and inconclusive, memento mori as much as full-blown compositions, Eastman’s scores now lend themselves to liberal, if not promiscuous, interpretation. Powerful though his music is, one suspects that at least part of its appeal lies in the story of his passion and sacrifice. At the Kitchen’s retrospective, Eastman’s music spoke boldly, as the saints urge Joan of Arc in his great prelude, yet it seemed incomplete without him, and I felt his absence as one might feel the presence of a ghost.

The most haunting work was not an Eastman composition, but rather an elegy by the singer and poet Tracie Morris, accompanied on electronics by the composer Hprizm. Drawing upon excerpts from Eastman’s Northwestern speech, Richard Pryor, and Billie Holiday’s “Crazy He Calls Me,” Morris cried, stammered, and growled, breaking off phrases before they could become intelligible; she returned repeatedly to the word “crazy,” the accusation that Eastman assumed, along with “nigger,” as a symbol of militant authenticity. The performance was a tribute to his courage, but also an acknowledgment of an irreparable loss. For all its radiance, the music of Julius Eastman will never be fully retrieved from the ruins he left behind.