As you enter “Klimt and Schiele: Drawn,” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, you are faced with a choice. Begin on the left, with Gustav Klimt’s Seated Woman in a Pleated Dress, and you will find yourself following Klimt down one wall of the single, large room; pick the right, with Egon Schiele’s The Artist’s Mother, Sleeping, and you are in his more colorful and astringent territory. Not until you have completed the whole circuit does it become clear that these two paths are also mirror images, each organized around the same rubrics: “Inner Life Made Visible,” “The Stuff of Scandal.” It is the curator Katie Hanson’s deft way of paying obeisance to the familiar coupling of the two artists—the heroic heralds, with Oskar Kokoschka, of Viennese modernity—while also insisting on their difference, even their irreconcilability.

The show’s exclusive focus on drawings only heightens this contrast, since these two artists took very different approaches to drawing. Most of the Klimt works in the show are preparatory sketches, which give only hints of the power of the final products; and the magnificence of Klimt’s major paintings has little to do with what we ordinarily think of as the virtues of drawings—spontaneity, naturalness. With Schiele, just the opposite is true: drawings for him were frequently ends in themselves, finished with watercolors and sold to collectors. Some of Schiele’s drawings in “Drawn” stand among his most powerful work, which cannot be said for any of the Klimts.

This contrast between the show’s two subjects is already present in the first drawings the visitor encounters. Klimt’s seated figure, feet together and knees apart like a child on a kindergarten rug, is a far cry from the erect and gorgeously decorated women in his best-known paintings, such as the portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. Yet there is still something monumental in the composition, which turns the woman into a three-leveled ziggurat—legs, torso, head. And there is an unmistakable excitement in her posture, leaning forward with clasped hands, and still more in her face: she has the kind of erotic avidity that, in Klimt’s great portraits and allegories, bursts into florid life. She sits on the verge of the new century—the drawing is from about 1903—waiting eagerly for something to happen, or to make something happen.

Schiele’s drawing of his mother from 1911, on the other hand, is a peaceful subject wrenched into disorienting shape. Rotated ninety degrees to the right, as it often is in reproduction, it would show a woman lying horizontally on a bed or couch. But in a favorite technique, Schiele displayed it vertically, turning a recognizable posture into an odd and tense one, as if the sitter is sleeping standing up. This effortful position seems to match, or explain, her haggard expression—if she is resting, it could not be deeply or peacefully. Her arms are concealed beneath blankets that are dirty, acidic blurs of watercolor, a striking contrast to the delicately modeled nose and eyes. One doesn’t have to know the details of Schiele’s difficult relationship with his mother—whom he blamed for insufficiently mourning his father’s early death—to see the ambivalence in this image. Tender yet unsettling and hard to read, the Schiele drawing is in every way more challenging than the Klimt it faces.

Clearly, if these artists are both modern, they are promising different modernities—which is only natural, considering that they belonged to different generations. Both Klimt and Schiele died in 1918, the last year of World War I, and of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that alternately celebrated and stifled them. “Drawn,” which includes sixty works from the collection of Vienna’s Albertina Museum, is the first of several exhibitions that will mark this centenary. (“Obsession,” a show of nudes by Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso, will open at the Met Breuer this summer, and there is a yearlong series of exhibitions in Vienna under the group title “Beauty and the Abyss.”) Yet Klimt was twice Schiele’s age in 1918: the older artist died of a stroke at the age of fifty-five, while the younger succumbed to the Spanish flu epidemic at just twenty-eight. Klimt, in other words, was a man of the nineteenth century, Schiele a product of the twentieth; and this may be the fundamental difference between two artists who were both considered scandalously avant-garde.

The difference in age and status did not stop Klimt from recognizing Schiele as a kindred spirit. At a time when Klimt was by far the most famous artist in Austria, he readily took the young Schiele under his wing, helping him find patrons and commissions. When they first met, in 1907, Schiele was a teenage student at Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts, already starting to rebel against his conservative teachers. (One anecdote has one of his professors shouting at him: “The devil has shat you into my classroom!”) “Drawn” includes two of Schiele’s drawings from the year of their meeting, portraits of a bearded, older man and of a girl; the latter, in particular, is proficient yet sentimental, with a mood of reverie, in a way that he would soon reject violently. Indeed, on his first visit to Klimt’s studio, Schiele brought several drawings along and asked the master if he had talent—to which Klimt replied ironically, “Much too much.”

Advertisement

Klimt’s own career had demonstrated that talent needed to be restive if it was to count for anything. Starting in the 1880s, he was a favorite of Vienna’s civic and imperial establishment, the recipient of several major commissions to decorate public buildings on the Ringstrasse in the heart of the city. Its development, on the site where the old defensive walls stood until they were finally demolished in the late 1850s, was crucial in the transformation of Vienna into a modern metropolis. Over the next decades the Ring was filled with pompous official buildings in a variety of architectural styles, which reflected the eclectic historical taste of the city’s newly dominant bourgeoisie.

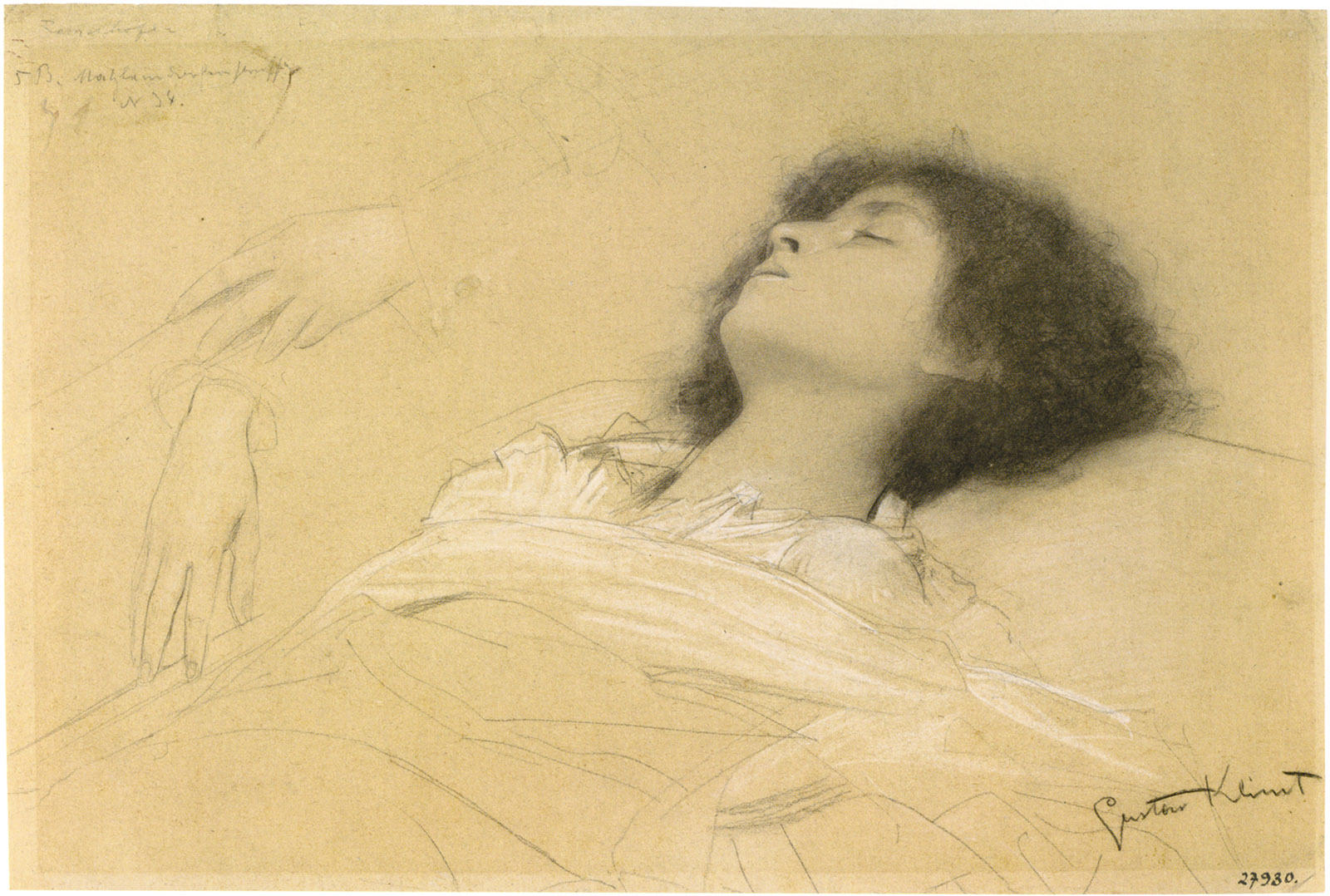

Klimt, who had graduated not from the Academy of Fine Arts but from the more practically oriented School of Arts and Crafts, was entrusted—along with his brother Ernst and Franz Matsch, who formed a working partnership—with the decoration of several of these buildings. Among them was the Burgtheater, which in drama-besotted Vienna served as a kind of civic temple. Klimt’s ceiling paintings of 1886–1888 depicted episodes from the history of the theater, and “Drawn” includes three early sketches for the section showing a performance of Romeo and Juliet at Shakespeare’s Globe. Within the logic of the show, they serve the same purpose for Klimt as the student sketches do for Schiele—demonstrations of an early mastery that the artist would soon rebel against. Klimt’s dying Juliet, peacefully reclining in white sheets and a white nightgown, can be seen as exactly the kind of idealized sleeping beauty that Schiele’s portrait of his mother refuses to be. The two other sketches—heads of spectators in the theater, an adult man, and a boy seen from behind—have far more character, with a lively immediacy.

But it was not in the direction of immediacy that Klimt was to evolve. On the contrary, his works of the 1890s and after can be seen as taking the public, mythicizing impulse behind the Burgtheater paintings and leading it in radical new directions. It was another commission for a public building that would lead to the most notorious and consequential episode in his career. In 1894, Klimt—again in partnership with Matsch—was chosen to produce the ceiling paintings for the Great Hall of the University of Vienna. The centerpiece of the commission was four paintings meant to represent the university’s traditional four faculties; Klimt was to be responsible for three of them, Jurisprudence, Medicine, and Philosophy. These were to flank a central panel, painted by Matsch, representing “the triumph of light over darkness”—a theme in keeping with the highest nineteenth-century ideals.

But when Klimt made his enormous paintings public—Philosophy was unveiled in 1900, with Medicine and Jurisprudence following over the next few years—it turned out that what he had painted was much more like the triumph of darkness over light. None of these canvases still exist—they are believed to have been destroyed at the end of World War II, when retreating Nazi troops set fire to the castle to which they had been moved for safekeeping—so we can judge them only from black-and-white photographs. But these make clear enough why they caused such a public outcry, whose echoes reached the highest levels of government.

Medicine, for instance, was represented by the goddess Hygieia, just as Klimt’s patrons might have expected. But here she is a cold and proud goddess, seen from below in dramatic foreshortening, her hair and dress almost dissolved into abstract patterns. Brandishing her traditional emblem, a snake, she appears alien, formidable, more hieratically Byzantine than reassuringly classical. As if this weren’t enough, Klimt’s Hygieia occupies only the lower central portion of the canvas; most of the painting’s action is taking place behind her back, seemingly without her knowledge. And that action is pure cosmic suffering, a vertical frieze or river of twisted and repining human bodies, with the skeleton of death taking its place among them. The professors of medicine couldn’t have been pleased with this way of thinking about their work, with its seeming dismissal of values like healing and compassion. The other two paintings are similarly bleak, saturated with a Schopenhauerian pessimism about the darkness of human fate and the extremely limited part that intellect can play in alleviating it.

Advertisement

In “Drawn,” we can catch glimpses of Medicine in three figure sketches—of a sleeping baby, a skeleton, and Hygieia herself. Though they can give little sense of the finished work, they are already powerful images. Even in her rudimentary state, Klimt’s Hygieia is a mysteriously authoritative presence; with her head barely sketched in, it is easy to see how much of her power comes from the exaggerated verticality of the figure, which allows her to look over the viewer’s head as if she disdained us. This masterful remoteness, here as with other Klimt women, carries an unmistakable erotic charge.

More straightforwardly erotic was the figure in the upper-left section of Medicine, a nude female whose outstretched arm seems designed to hold the pageant of suffering humanity at a defensive or despairing distance. Critics who didn’t object to the work’s pessimism could fasten their unease on this figure, with its frontal nudity seen from below—again, not the kind of thing one would expect to look up and see in an institution of higher learning. In the setting of this exhibition, Klimt’s drawings of reclining nudes appear less scandalous, but they are still powerfully suggestive in their poses of dreamy abandon. Even if we weren’t told that Portrait of a Woman in Three-Quarter Profile was a study for the figure of Lasciviousness in another of Klimt’s allegorical works, her slyly turned head and eager expression would leave no doubt what she meant to communicate.

The Vienna of Klimt and Schiele was also, of course, the city of Freud, who was perhaps the only member of the university’s faculty of medicine who would have completely endorsed the intention of Klimt’s painting. The Interpretation of Dreams was published in 1900, three years after a group of rebellious, cosmopolitan artists broke with the Viennese art establishment to create the Secession, under the presidency of Klimt. Indeed, it is almost impossible not to see Klimt and Schiele in part through a Freudian lens, as liberators of human sexuality from the forces of convention and repression.

Yet here, too, their paths diverged in very important ways. Klimt can be seen as the great artist of sublimation: in textbook Freudian fashion, he erects allegories and symbols to channel and heighten the force of sexuality. His portraits of Viennese society women, no less than his Pallas Athena, are masterpieces of such sublimation, with each female figure transformed by imposing artifice into a kind of goddess. Partly, this process depends on Klimt’s use of gold leaf and mosaic effects, which have always been popular with audiences—though they also contribute to what Emily Braun has called the “Klimtophobia” of some critics. Yet the portrait studies of Amalie Zuckerkandl included in “Drawn” show that the queenly effect of Klimt’s portraits is not merely a matter of surfaces; it has just as much to do with their architecture, and with the painter’s dramatic instinct for gesture and posture.

If Klimt successfully harnesses the power of sex, Schiele takes a directly opposite course. His drawings give us the chaos of neurosis, when sexuality has turned on its possessor and become a pursuing Fury. The subjects of Freud’s case studies—the Rat Man or the Wolf Man—must have felt much the way Schiele appears in his Nude Self-Portrait of 1910: haggard, tortured, reduced to a harsh, mottled slash. The nimbus of white surrounding his body seems less like a halo than an electric shock, an impression reinforced by the way the hair stands up wildly in all directions.

Why does the suffering communicated in this work seem to have such a clear sexual component or etiology? Partly it is Schiele’s decision, which here seems almost like a compulsion, to display himself in the nude. This is plainly not a gesture of candor or innocence, but the reverse: Schiele clutches his arm to his torso in a pose reminiscent of Adam feeling shame about his nudity for the first time. (Arms, in Schiele, are frequently put in the service of expressive distortion and contortion.) His face is deeply expressive of a disgust that can only be self-disgust; his clamped lips seem to be trying to get rid of a bad taste.

But it is also, of course, the expectations formed by Schiele’s work as a whole that prepare us to discover sexuality in Nude Self-Portrait. For Schiele, pornographic drawings were both an important source of income and a major avenue of artistic exploration. These are works of tainted eroticism, with the artist demanding a confession of complicity from the viewer. “Drawn” only touches on this area of Schiele’s work, with drawings such as Female Lovers of 1915. Here two women, one nude and one clothed in an acid-lime-green shift, are posed in an embrace that has more to do with alienation than communion. The nude woman’s head is bent backward, her gaze turned away from her partner’s face, which is horribly like the face of a doll, with staring pinpoint eyes.

But “Drawn” does not include any of Schiele’s most defiantly obscene works, such as his images of pubescent girls displaying their bodies or masturbating. The closest it gets is the 1910 Seated Nude Girl, whose disturbing force comes less from any implicit sexuality than from the framing of the gaunt, meek figure. The top of her head grazes the edge of the sheet, and her weirdly elongated arm abruptly ends at the wrist, with the hand unfinished.

When it does attempt to address the question of Schiele’s sexualization of children, “Drawn” is evasive. Under the rubric “The Stuff of Scandal,” the show includes three drawings Schiele made while in prison in 1912, in the small Austrian town of Neulengbach. Schiele’s arrival in the town, where he lived openly with his model and mistress Wally Neuzil, immediately caused a great deal of talk. Things got worse when the police were informed about the way Schiele kept open house for local children, whom he would allegedly ask to pose nude. When the police called on Schiele, they discovered that the walls were covered with pornographic drawings. He was arrested, initially on the charge of seducing and kidnapping an underage girl; while he was acquitted of those crimes, he was found guilty of displaying pornography to minors. All told, he spent twenty-four days in a local jail.

The account of this episode in the wall text in “Drawn” minimizes Schiele’s culpability. “Schiele had returned the girl home safely,” we are told, and there is a suggestion that the whole episode was simply another example of the philistinism that all modern artists glory in having fought against. But the truth is that Schiele obviously did use underage girls to pose for pornographic works, in a way that would probably be punished even more harshly today than it was in Austria a hundred years ago. If Balthus’s ambiguous Thérèse Dreaming could recently become a subject for protest at the Metropolitan Museum, there is no reason why Schiele’s much more explicit drawings of children should escape controversy. It is plainly to head off such controversy that “Drawn” includes another section of wall text headed “Artists and Personal Conduct,” which notes that “Schiele has long had a reputation as a transgressive at society’s edges.” But of course, in this setting, that sounds like a compliment.

All this makes for uncomfortable viewing when we come to Schiele’s prison drawings, which are bathetic and self-pitying in the extreme, starting with their titles. Hindering the Artist Is a Crime, It Is Murdering Life in the Bud! portrays Schiele in the same rotated position that he used in the drawing of his mother: he seems to be reclining standing up, with his head askew atop a shapeless coat. The artist’s wide eyes and meek mouth demand pity; the same face, in Prisoner!, insinuates a profound indignation. Schiele seems so confident in the script he is acting out—the modern morality play of the persecuted artist—that he leaves no room for genuine exploration of his plight.

For the challenging truth is that sexuality, in both Klimt and Schiele, is a force more primal than morality. This is another Freudian intuition that these artists shared; but they saw more deeply into it than we tend to do when we calmly consider sexual liberation to be a mark of progress. In Vienna in the early twentieth century, it was clear that setting sexuality free meant loosing a powerful and potentially destructive force, one that can domineer and seduce, as in Klimt, or entrap and torment, as in Schiele. These are not artists to whom one can turn for images of a rational or equitable eroticism, which to them would have been a contradiction in terms. Part of the purpose of exhibitions like “Drawn” is to provide a contained environment in which such dangerous energies can be contemplated without being approved—a distinction upon which rests the very possibility of creating art.