Early in Asymmetry, Lisa Halliday’s astounding first novel, Alice, a young assistant editor at a large publishing house, comes across a stray paper in the apartment of the much older writer she is sleeping with. On it are a few typed lines, including this: “An artist, I think, is nothing but a powerful memory that can move itself through certain experiences sideways…” The quote bears no attribution, but it comes from the nineteenth-century novelist Stephen Crane. It will resurface, as so many other details in Alice’s story, in Asymmetry’s second section, a seemingly disconnected tale told from the point of view of an Iraqi-American economist detained at Heathrow Airport.

It is also an apt précis for what Halliday sets out to achieve in her deceptively smart novel. Deceptive because, though it tells two relatively straightforward stories—one a coming-of-age love story; the other the tale of an uprooted man searching for his lost brother—it does so while breaking away from the conventions of realist fiction. Halliday relies instead on omissions and inferences. She arranges the first section of the novel (titled “Folly”) into short, associative bursts reminiscent of Renata Adler’s Speedboat (1976) or, more recently, of Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation (2014). And she interlays her book with various texts, from Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963) to an abortion manual, ending it with an inspired set piece that reads like a spot-on transcript of a BBC Radio 4 program.

But I’m afraid the above description risks making Asymmetry appear heavy-handed or pretentious. It is anything but. In fact, one of its many pleasures lies in its adherence to the classical novelistic tradition of a forward-moving story (two, in this case) well told. Halliday’s impressively assured yet light touch moves through the novel sideways, which is to say porously and without judgment.

When we first meet Alice, she is sitting on a bench on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, reading a book:

She was considering (somewhat foolishly, for she was not very good at finishing things) whether one day she might even write a book herself, when a man with pewter-colored curls and an ice-cream cone from the Mister Softee on the corner sat down beside her.

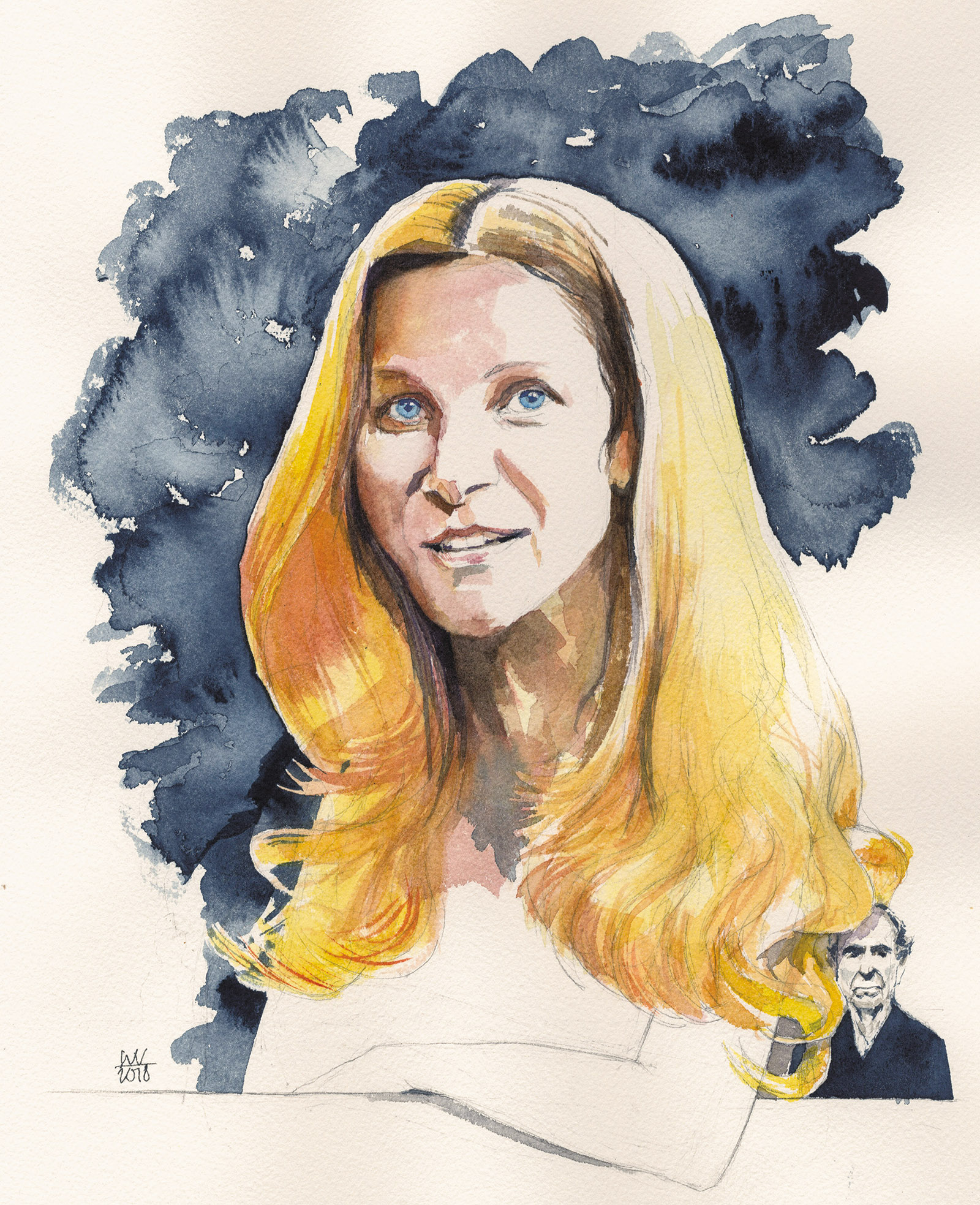

She recognizes him instantly, and so do the joggers bobbing by. He is Ezra Blazer, a writer Halliday consciously modeled on Philip Roth, in order, she said in an interview, to “maximize the ‘anxiety of influence.’” (And perhaps out of familiarity: Halliday had a relationship with Roth when she, like Alice, was in her twenties and working in book publishing, and the two have since remained friends.) His influence is great indeed, for Alice is an aspiring writer, though as yet unhatched. She certainly has the eye of one—noticing the way in which cars driving in the rain appear to be traveling faster than when it’s dry; how a photo Ezra had taken of her “was almost a beautiful photograph,” but the problem “was its Aliceness: that stubbornly juvenile quality that on film never failed to surprise and annoy her”; or the fleeting look of irritation that crosses Blazer’s face when he catches sight of the “white cone of discarded typescript” lining his wastebasket.

But the unspoken understanding between them is that Alice’s ambition, so far as it exists, must remain secondary to Blazer’s work. One of the novel’s asymmetries is the inherent power imbalance between an impressionable young woman and a successful older man. (I may be complicit here, too, instinctively referring to her by her first name and to him by his last.) Blazer determines where and when they will meet—his apartment, after his writing day is done—and for how long. Whenever he wants Alice gone, all he has to do is sing “The party’s over…” and she staggers home, “her belly full of bourbon and chocolate and her underwear in her pocket.” At the start of their relationship, Alice jots down her phone number on a bookmark and hands it to him. Blazer tells her, “You’ve lost your place.” We suspect he’ll turn out to be right in more ways than one.

The imbalance quickly turns financial. Alice lives without an air conditioner, so Blazer buys her one, showering her with other gifts as well—a “sensible” watch, a Chanel eau de parfum, a luxurious Searle coat that makes her feel “pampered and invincible.” This is done not so much in the possessive manner of a high-roller toward his trophy wife (though there is an aspect of that, of course) as in the benevolent spirit of an older uncle, say, besotted with a precocious niece. Along with the presents, Alice also gets an education. “It’s Ca-MOO, sweetheart. He’s French,” Blazer tells her. When he sees her reading a biography of Hitler, he advises her to steer clear of sentimental accounts of the Holocaust and to focus instead on Primo Levi, Gitta Sereny, and Arendt. By the by, he offers her encouragement of sorts, saying that her conspiracy-theorist father is a writerly “gift” and that she should write what she knows. “Don’t worry about importance,” he advises. “Importance comes from doing it well.”

Advertisement

Books—and a passion for baseball—are what unite them, and Halliday is clearly having fun conjuring the strange ins and outs of a business in which Blazer is the undisputed deity and Alice a mere mortal. Time in the novel is marked by a running gag about Blazer missing out on the Nobel each year. There’s a stinging moment in which Alice finds, tossed away, the galleys of a novel by someone she knows, with a letter asking Blazer for a blurb “still paper-clipped to its cover.” There’s a funny aside about her firing off an e-mail at work “rejecting another novel written in the second person.” And some wonky inside baseball, too. When Alice visits Blazer’s summer home and tells him that she just killed “the biggest wasp,” he can’t help himself: “I thought George Plimpton was the biggest wasp,” he says.

At first glance, theirs is a familiar story—of docent and pupil, artist and muse. But the Alice–Blazer arc doesn’t read as a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of gender, sex, and power. It is—as life is—more complicated than that. On the one hand, we get to inhabit Alice’s perspective, so that her role as muse is nicely subverted. On the other hand, she remains elusive, kept by Halliday at a third-person remove. And while we sense that Alice and Blazer are wrong for each other—“for a moment Alice saw what she supposed other people would see: a healthy young woman losing time with a decrepit old man”—there is, nonetheless, a tenderness between them that is absent from Alice’s interactions with more “suitable” young men. (In one short but skewering sketch we learn of a boy she has sex with once: he is an assistant in the Sub-Rights Department; they meet at a “retirement thing” for a company editor; in the morning he puts on his corduroys and bolts. Enough said.)

Meanwhile, Alice and Blazer’s relationship, lopsided as it is, starts to tilt the other way, with Blazer becoming increasingly dependent on Alice to run errands for him after he undergoes an unsuccessful back operation, and to inject a dose of liveliness into his veins. “While they were doing one of the things he wasn’t supposed to do” begins a typical encounter between them. The more time they spend together, the more daunting his influence: “Ninety-seven years they’d lived between them, and the longer it went on the more she confused his for her own.” They use a fine scrim of humor to veil and unveil their age difference. Alice tells Blazer of a dresser she bought with the money he gave her—a “vintage 1930s piece,” she says. “Like me,” he replies. Nor is she herself above ribbing the multiple-Pulitzer-Prize-winning author. When he inquires after her family, asking if her grandmother is still alive, she says: “Yep. Would you like her number? You’re about the same age.”

Contrary to Blazer’s advice, however, Alice isn’t interested in writing what she knows. She is drawn to conflict and world affairs—“Writing about myself doesn’t seem important enough,” she tells him. He reads Keats in bed; she reads about the latest London Tube bombings. She also pores over Jon Lee Anderson’s The Fall of Baghdad, at one point wondering whether “a former choirgirl from Massachusetts might be capable of conjuring the consciousness of a Muslim man.” (The second section of the novel will serve as a kind of answer to that question.) Still, when the United States invades Iraq, the war touches their lives only tangentially. They share a praline tart as President Bush announces the invasion on television. This is war as seen from the comfortable confines of 85th and Broadway.

Not so with the second part of the novel (entitled “Madness”), in which the currents of war soak every corner of human experience. The characters in this section are not on the front line—they live in Los Angeles, Brooklyn, and Iraqi Kurdistan (a relative bastion of peace compared to the rest of Iraq)—and yet their lives are hemmed in by events larger than themselves. Halliday deftly depicts how conflict translates to an obscene waste of time, from circuitous car rides to avoid roaming kidnappers in the desert, to hours spent in windowless holding rooms on whose walls are taped up signs with messages such as “SLEEPING ON THE FLOOR IS NOT ALLOWED.” Naturally, this section, which features an inept bureaucracy and monotonous questioning, flags a little. Then again, it is animated by the perceptive consciousness of a first-person narrator with whom we become much more intimate than with Alice. This is intentional: Halliday has said in interviews that although she shares some biographical details with her first protagonist, it is Amar Jaafari—the narrator of Asymmetry’s second part—whose thoughts and temperament more closely resemble her own.

Advertisement

Amar is anxious, calculating, philosophical. He chose economics as a profession out of agreement with Calvin Coolidge that it represented “the only method by which we prepare today to afford the improvements of tomorrow.” Like Alice, he is a keen observer of his surroundings, though he worries that the recollections that haunt him—the very events we are reading about in a series of flashbacks—are unreliable, that his memory is nothing but a secondhand repository of old photographs and stories.

Amar’s Iraqi parents conceived him in Baghdad, but he was born on a plane high above Cape Cod, causing immigration officials to scratch their heads over his nationality. This straddling of two cultures is a defining feature of the Jaafaris. Amar’s parents want their children to transcend their background and fully integrate into American society; Amar’s admired older brother, Sami, yearns to return to Baghdad and attend medical school. Sami imagines a future in which Iraq would flourish—a time when, “instead of Hawaii, honeymooners would fly to Basra” and the Lions of Mesopotamia would win the World Cup. “Just you wait, little brother. Just you wait,” he tells Amar.

Like his brother, Amar enrolls in medical school, but at an Ivy League university in the US (there are hints of Yale). There he falls in love with the lead actress in a student production of Three Sisters. It is so “overwrought,” Halliday writes, that “it gave you the impression the twenty-year-old at the helm could now cross direct a play off his list of things to do before winning a Rhodes scholarship.” They become a couple and, after college, get an apartment together in Manhattan.

But Amar is adrift and, on a whim, he accepts an internship in London, where he befriends Alastair, a world-weary war reporter so addicted to the thrill of battle that he feels morally culpable. Alastair tells Amar:

When I go home, when I go out to dinner or sit on the Tube or push my trolley around Waitrose with all the other punters and their meticulous lists, I start to spin out. You observe what people do with their freedom—what they don’t do—and it’s impossible not to judge them for it…. You think about how we all belong to this species capable of such horrifying evil, and you wonder what your responsibility to humanity is while you’re here, and what sort of game God is playing with us—not to mention what it means that generally you’d prefer to be back in Baghdad than at home in Angel with your wife and son reading If You Give a Mouse a Cookie.

War, in other words, shapes a consciousness. It renders such American concepts as New Year’s resolutions laughable, because, as Amar’s bewildered relatives say:

Who says there won’t be a curfew tomorrow, preventing you from going to the gym or running in the park after work? Or who says your generator won’t give out and then you’ll have to read with a flashlight until the batteries die and then with a candle until that burns down, and then you won’t be able to read in bed at all—you’ll just have to sleep, if you can?

Anyone who has lived long enough in the Middle East will recognize the sentiment. And yet, amazingly, Halliday herself has never visited Iraq or Kurdistan, despite her fine-grained evocations of the places (down to a Sulaymaniyah fast-food joint called MaDonal). She said she relied instead on “an enormous amount of research.” It’s a testament to her novelistic skills that this material comes fully to life without her once belaboring the book with her study notes.

By the time Amar is being held up at the airport it’s 2008, and his brother’s prophecy could not be further from the truth. Baghdad is a war zone. American troops play cards with a military-issued deck that features fifty-two of Iraq’s most-wanted men. “Chemical Ali led the flop,” Halliday writes. Sami’s hospital, where he works as a corrective surgeon, used to specialize in nose and breast jobs, but now the doctors spend their days “staunching rocket wounds, tweezing shrapnel, and swaddling burns.” When Amar and his parents visit Kurdistan in 2003, they pass a billboard advertising local elections. “So that we might leave a better country for our children,” the placard says, making it, Amar thinks, “somewhat difficult not to interpret the caption to mean: Yes, for our generation it’s probably a lost cause.”

The asymmetry of geography—arguably the most consequential of life’s lotteries—is a recurring preoccupation of Halliday’s novel, as is our ability to extend past it, “to penetrate the looking-glass and imagine a life, indeed a consciousness, that goes some way to reduce the blind spots in our own.” Alice has managed to see past the looking-glass. This will become apparent in the book’s coda—a radio interview with Ezra Blazer—where we learn, almost in passing, how the two halves of the novel fit together as a narrative. It is as elegant an answer as you have come to expect from Halliday. While both sections echo each other throughout, the echoes are never made explicit. A description of an abortion clinic resurfaces; Primo Levi’s memorable depiction of the Buna factory in Auschwitz as “the negation of beauty” is applied to Baghdad. Such motifs whisper rather than scream. And that, too, appears intentional on the part of an author who seems to demand—and reward—exactitude from her readers. Nothing in Asymmetry feels didactic or contrived; it is the very opposite of that overwrought production of Three Sisters that Amar attends.

“I’m always highly irritated by people who imply that writing fiction is an escape from reality,” Flannery O’Connor wrote in Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose (1969). “It is a plunge into reality and it’s very shocking to the system.” To prove her point, O’Connor listed the example of a short story called “Summer Dust” by the American novelist Caroline Gordon, which she described as being divided into sections that don’t, at first, seem to cohere. Reading Gordon’s story, O’Connor went on, is

rather like standing a foot away from an impressionistic painting, then gradually moving back until it comes into focus. When you reach the right distance, you suddenly see that a world has been created—and a world in action—and that a complete story has been told, by a wonderful kind of understatement.

Fifty years on, O’Connor’s praise can be applied, word for word, to Asymmetry, with its own “world in action” and “wonderful kind of understatement.” To read Halliday is to feel a similar snap into focus, a shocking “plunge into reality.” The effect, as O’Connor predicts, is impressionistic—concerned with movement and a subjective perception of reality. Halliday is only a realist to the extent that Crane was: up to a point. Both writers show us how realism breaks down when it comes to war, which makes no narrative sense. War exposes free will as the illusion of the privileged. It defies structure. So Halliday went ahead and created her own.

Puzzlingly, the denouement and last word in Asymmetry belong neither to Alice or Amar—our two protagonists—but rather to Blazer, the aging white man. His retrospective interview appears to be the sign of one dimming generation making way for the next. Despite his advanced age, Blazer remains an incorrigible flirt. He ends the interview, and the novel, with a question to the radio host that, at the beginning of Asymmetry, he posed to Alice: “Are you game?” It is a question for Halliday’s readers as much as for these two women—whether we are willing to set aside our preconceptions and let the novel play with our imagination, leave us in a state of heightened alertness, slightly changed, as Alice’s apartment appears to her after a rendezvous with Blazer, when “everything was exactly as she’d left it, but her bedroom looked too bright and unfamiliar somehow, as though it now belonged to someone else.”