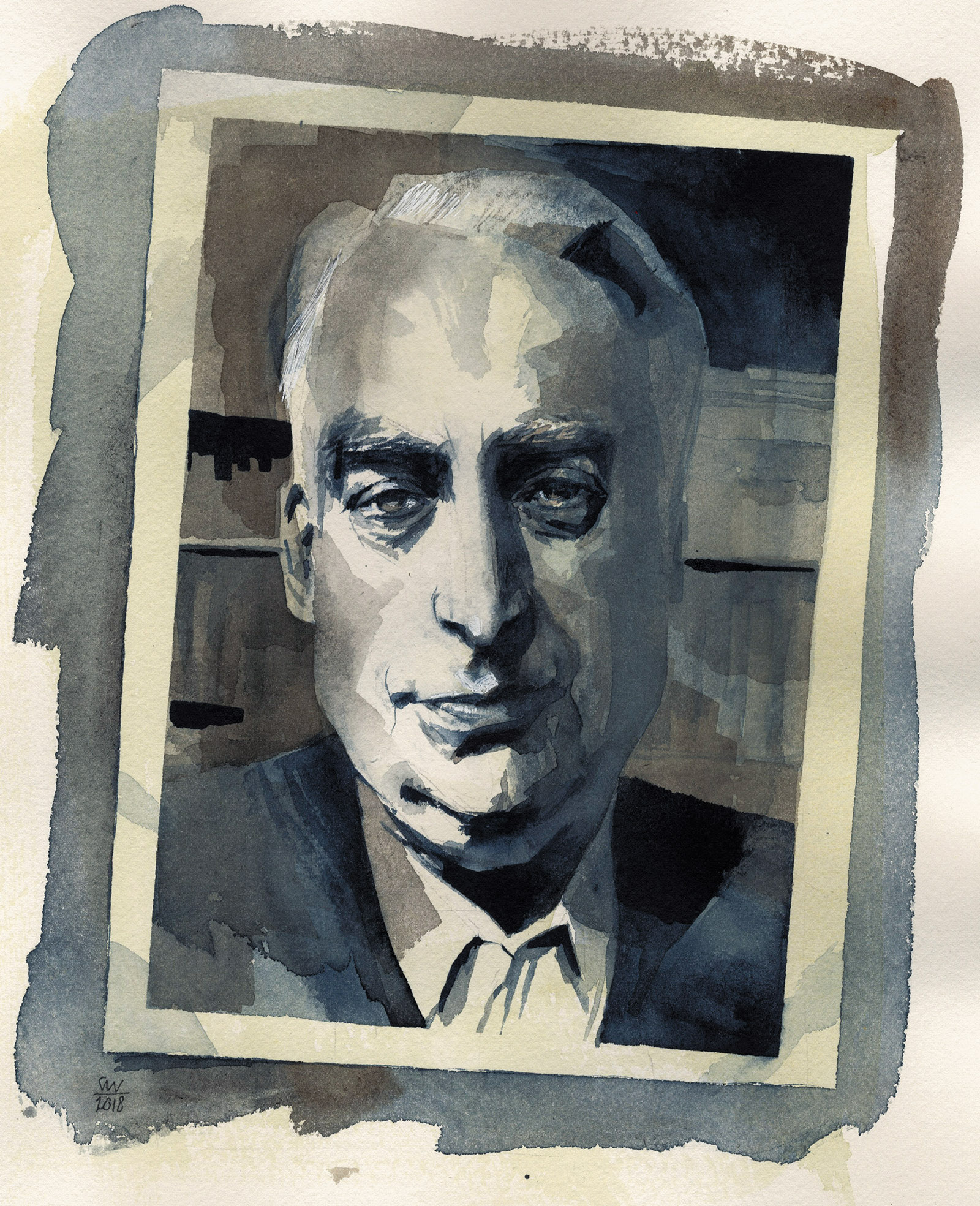

In 1978, Roland Barthes embarked on a series of lectures entitled “Preparation of the Novel” at the Collège de France. The novel? Which novel? The one that Barthes had long planned to write, of course. But he didn’t know quite how to begin, and he kept getting distracted. As Laurent Binet writes in his recent novel, The Seventh Function of Language, “All year, he has talked to his students about Japanese haikus, photography, the signifier and the signified, Pascalian diversions, café waiters, dressing gowns, and lecture-hall seating—about everything but the novel.” The novel never got written. On February 25, 1980, Barthes was run over by a laundry van while crossing the street after a lunch with François Mitterrand. He died a month later.

There was always something incongruous about Barthes’s ambition to write a novel. He made no secret of being bored by the great novels of the nineteenth century: “Has anyone ever read Proust, Balzac, War and Peace, word for word?” Although he had been a champion of the experimental “new novel” of Alain Robbe-Grillet and Michel Butor in the 1950s, his best writing was inspired by photography, theater, painting, music, and, not least, consumer culture. Still, he remained haunted by the unwritten novel, as if it were proof of his illegitimacy as a mere critic. According to Tiphaine Samoyault in her superb biography, Barthes often felt like an impostor, which might explain the endearing notes of self-deprecation that punctuate his writing. As the novelist Philippe Sollers writes in his enjoyably grouchy homage, The Friendship of Roland Barthes, “he didn’t realize that what he had done was considerable.”

Nor did he realize that, by failing to write the novel, he had instead invented a new, aphoristic genre, a bricolage of aesthetic reflection, memoir, philosophy, and cultural criticism: a “New New New novel,” as Robbe-Grillet called it. Barthes’s influence left its mark on the novels of his friend Italo Calvino and his former student Georges Perec. Writers like Geoff Dyer, Ben Lerner, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, and Maggie Nelson are almost unimaginable without Barthes, not to mention the school of contemporary French writing known as “autofiction,” associated with writers such as Annie Ernaux.

Barthes claimed that he was incapable of writing an old-fashioned novel because he could not invent “proper names.” Yet he did create one unforgettable character: Roland Barthes, or “R.B.,” as he called himself in his 1975 memoir Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes. Although he never entirely abandoned the rarified language of theory, most of his work can be read as a self-portrait, a discreet yet impassioned record of his tastes, his moods, his loves, and his vulnerabilities. As Susan Sontag put it, he was a “devout, ingenious student of himself.”

In his memoir, Barthes portrays himself as a self-effacing aesthete captivated by modernist innovation but secretly, a bit guiltily, a classicist, “in the rear guard of the avant-garde”; a plump sensualist who dislikes the conventions of bourgeois society but not so much that he wants to sacrifice its pleasures on the altar of a puritanical revolution; a gay man who lives with his mother, devoted simultaneously to the fleeting thrills of cruising and the dependable comforts of domesticity. He is a flirt, easily bored, invariably dissatisfied. If he is committed to anything, it is to the infinitely paradoxical nature of the self, and to the refusal of any attempt to deny it in the name of a singular meaning. He wrote of himself, “He dreams of a world which would be exempt from meaning (as one is from military service).”

Barthes wasn’t the most original of postwar French thinkers; he did not transform the way we think about kinship relations, prisons, or linguistics, much less (as Samoyault unconvincingly claims) open “a path for thinking about a new order of the world and our knowledge of it.” Nor did he aspire to lead an intellectual revolution: more than any of his peers, Barthes discarded the heroic model of the “universal intellectual” that Sartre had pioneered. But he was the only French theorist who can be said to inspire genuine love—a subject on which he wrote some of his most memorable pages. The joy of reading him is that you always feel you’re in the presence of a friend who accepts your moods and imperfections, and sympathizes with your desire not to be pigeonholed.

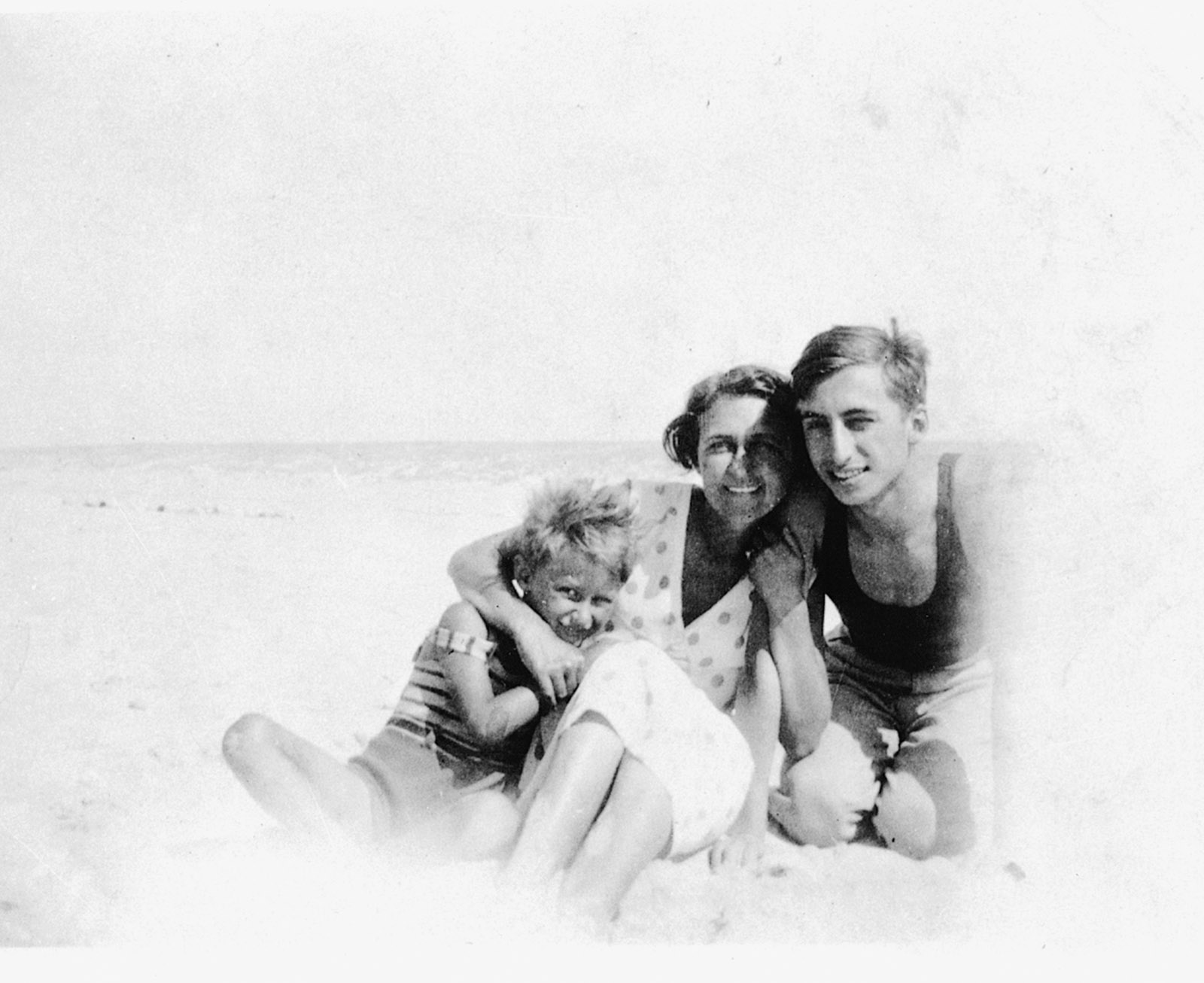

Barthes was born in 1915 in Cherbourg. When he was eleven months old, his father, an officer in the merchant navy, was killed at sea by the Germans; the body was never recovered. The state stepped in to pay for Roland’s living expenses and his education. His mother, Henriette, a bookbinder, had little money of her own but came from a highly cultured Protestant family. Her father had been a well-known scientist and colonial officer in West Africa; her mother ran a literary salon where Paul Valéry was a frequent guest. Henriette moved with her son to Bayonne, a small port town in the southwest where they were among the few Protestants, a status that, along with his early awareness of his homosexuality, left him with an acute sense of belonging to a minority.

Advertisement

He grew up in Bayonne and Paris, where his mother found an apartment in 1924. His geography scarcely changed as an adult: he divided his time beween his apartment in Paris and his house in Urt, hardly ten miles from Bayonne, where he set up an office identical to his home office on the rue Servandoni, next to Saint-Sulpice. Barthes needed such routines or, as he put it, “structures,” to write. The foundational structure was his bond with Henriette, with whom he lived until her death. Nothing would threaten it: not her tempestuous love affair with André Salzedo, a Jewish industrial ceramist and a married man, with whom she had a son, Barthes’s half-brother Michel, in 1927; or his own nocturnal adventures (he always returned home after cruising). As he wrote in his memoir, “No father to kill, no family to hate, no milieu to reject: great Oedipal frustration!”

As a student in Paris at the Lycée Montaigne and later at Louis-le-Grand, Barthes immersed himself in all that was new: the music of Debussy, the poetry of Mallarmé, the writings of Nietzsche and Gide. He flirted with writing a novel, but complained to his friend Philippe Rebeyrol (later a distinguished diplomat) that the novel was “by definition an anti-artistic genre,” too burdened by psychology: he wanted to write something in “the ‘tonality’ of Art.” (In any case, his life was “just too pleasant” to write a novel.) Instead he practiced the piano, wrote sonatinas, and took singing lessons with Charles Panzéra, whom he would later use to illustrate his concept of the “grain of the voice,” the trace of “the body in the voice as it sings, the hand as it writes, the limb as it performs.” Theater was his other passion: at the Sorbonne, he helped found the Groupe de théâtre antique and performed in its productions. His experiences onstage left him with what Sontag called a “profound love of appearances.”

In the era of the Popular Front, Barthes was an instinctive antifascist, an admirer of the moderate Socialist leader Jean Jaurès: “Everything he says is wise, noble, human and above all kindly.” In a 1939 letter he wrote eloquently of his “hatred against the stench of this country,” but he steered clear of revolutionary rhetoric. (“I am liberal in order not to be a killer,” he wrote in his memoir.) He was, in any case, fighting a more personal war with pulmonary tuberculosis. In 1942, Barthes was confined at the sanatorium of Saint-Hilaire-du-Touvet. He spent the last year of the war lying for eighteen hours a day in a reclined position, with his head lowered, in silence.

At Saint-Hilaire Barthes fell in love with a fellow patient, Robert David. His letters to David, which are reprinted in Album (a newly translated selection of his correspondence), prefigure the themes he would explore in his 1977 book A Lover’s Discourse:

Love illuminates for us our imperfection. It is nothing other than the uncanny movement of our consciousness comparing two unequal terms—on the one hand, all the perfection and plenitude of the beloved; on the other hand, all the misery, thirst, and destitution of ourselves—and the fierce desire to unite these two such disparate terms.

Remarkably, Barthes seems never to have suffered the torments of the closet; he accepted his desires without guilt or ambivalence. “I’m already really quite self-affirmed,” he wrote a heterosexual friend in 1942, though, discreet as ever, he added that “self-affirmation mustn’t become ostentation.”

By the time Barthes left the sanatorium in 1946, he was, in his own words, “a Sartrian and a Marxist.” He had fallen under the influence of another patient, a Trotskyist survivor of Buchenwald who had impressed him as much for his personal qualities—“the moral freedom, the serenity, the elegant distance,” as Samoyault puts it—as for his analysis of the class struggle. Barthes’s Marxism was heterodox and deeply anti-Stalinist. “Communism cannot be a hope,” he wrote to Robert David. “Marxism yes, perhaps, but neither Russia nor the French Communist Party are really Marxist.”

That conviction was reinforced in Bucharest, where he taught at the French Institute in the late 1940s. Romanian culture was then being purged of “Western” influences, including homosexuality. Barthes, who shared an apartment with his mother above the French library, did his best to protect its collection from the local censors, and was soon appointed France’s cultural attaché, before being expelled. In a brilliant paper on the semiotics of the new “Romanian science,” he showed how “nationalism” and “cosmopolitanism,” epithets for “Western” feelings, were transformed into the virtues of “patriotism” and “internationalism” when applied to communism.

Advertisement

Barthes deepened his critique of Stalinist writing, in which the “sole content” of language is “the separation between Good and Evil,” in his first book, Writing Degree Zero (1953). Although he still considered himself a Marxist, he had seen in Bucharest how easily Marxism could lend itself to “police-state writing”—and to aesthetic banality. French Communist writers were “keeping alive a bourgeois writing which bourgeois writers have themselves condemned long ago.” He also implicitly distanced himself from his hero Sartre, who had defined revolutionary prose as an expression of political commitment.

For Barthes, writing was revolutionary only insofar as it was revolutionary in form, and the qualities he admired in radical literature were opacity, complexity, and elusiveness, a defiance of the communication that Sartre had seen as its goal: “Rooted in something beyond language, it develops like a seed, not like a line.” He advocated a “neutral writing,” cleansed of symbolism, psychology, and self-conscious literariness, like the flat, inexpressive style of Meursault, Camus’s narrator in The Stranger. “Literature is like phosphorous,” he wrote. “It shines with its maximum brilliance at the moment when it attempts to die.” As Samoyault astutely observes, rather than denounce Sartre, Barthes “incorporated”—and transcended—him.

The writer Barthes championed most passionately in the 1950s was Brecht, who had created a theater “purified of bourgeois structures” that at the same time avoided the pieties of left-wing didacticism. Brecht’s Marxism, Samoyault writes, supplied Barthes with “a method of reading, a principle of demystification.” Barthes used this method, along with the tools of structuralist linguistics, in his 1957 collection of newspaper columns, Mythologies. In sly, pithy essays on wrestling matches, steak-frites, cruises, striptease, Greta Garbo’s face, Einstein’s brain, and the new Citroën, he unveiled the process of “mystification which transforms petit bourgeois culture into a universal nature.” The book soon became nearly as mythical as its subjects, for its sharp critique of French consumer culture at the height of the trente glorieuses. But what distinguished Barthes from the dour analysts of the Frankfurt School was, as Samoyault writes, his playful ability to “connect desire with critique”: the essays in Mythologies have “a certain theatricality…both magnificently comic and at the same time pedagogic.”

Published against the backdrop of the war in Algeria, Mythologies was also Barthes’s most radical book, an evisceration of the self-congratulatory myths that underpinned France’s mission civilisatrice in the colonies. “Wine’s mythology,” for example, did not go unappreciated by “the big Algerian settlers who impose on the Muslims, on the very land of which they have been dispossessed, a crop from which they have no use, while they actually lack bread.” In his concluding theoretical chapter, Barthes examined a Paris Match cover showing a black soldier saluting the tricolor—a “good Negro who salutes us like one of our own boys,” he acidly observed—to show that “myth hides nothing: its function is to distort, not to make disappear.”

Barthes was not, however, a man of the barricades. When the writer and philosopher Maurice Blanchot asked him to sign the 1960 “Manifesto of the 121,” a declaration in support of insubordination against the Algerian war, Barthes declined, explaining that he felt “repugnance toward anything that could resemble a gesture in the life of a writer.” The heroics of intellectual engagement, and the calcified “doxa” he felt they encouraged, were anathema to him. He recoiled from public debate, and harbored a profound bias against the spoken word. (Fascism, he said, is “any regime that not only prevents one from speaking but above all obliges one to speak.”) He did not conceal his erotic leanings—he dedicated the first volume of his Critical Essays, published in 1964, to his lover François Braunschweig, an eighteen-year-old law student—but the “political liberation of sexuality” struck him as “a double transgression, of politics by the sexual, and conversely.” His own morality, he wrote, was “the courage of discretion”: “It is courageous not to be courageous.”

When the student demonstrations of May 1968 broke out, Barthes was hurt by the graffiti that said “Structures do not take to the streets,” but, with his horror of the spoken word, he had little sympathy for the movement’s speechifying, and he was now a middle-aged member of the establishment, chairman of the sixth section of the École pratique des hautes études. Nor could he deny having been infatuated with structuralism’s “dream of scientificity.” From the mid-1950s until nearly the end of the 1960s, he had been a diligent student of Ferdinand de Saussure, Roman Jakobson, and other linguistic theorists, applying their insights to everything from Michelet and Racine to the language of fashion and the Eiffel Tower. But Barthes eventually chafed against the rigidity of structuralism, and abandoned it much as he had Marxism: “quietly and without fuss, on tiptoe as always,” as Robbe-Grillet remarked.

By May 1968 he had already embraced the next trend, later known as “poststructuralism,” which celebrated the endless play, the restless and fugitive nature of signs. Interpretative systems, he decided, were a kind of tyranny imposed on the reader, and structuralism was no less guilty of this than Marxism and Freudianism—a conclusion he reached around the same time as his friend the “toujours fidèle” Susan Sontag did in Against Interpretation. In his 1968 essay “The Death of the Author,” he argued that reading itself had to be liberated from the repressive “function of the author.” He showed what the liberation of the reader might look like in two books published in 1970: S/Z, a virtuosic, paragraph-by-paragraph reading of a little-known Balzac short story about a castrato singer disguised as a woman, and Empire of Signs, his exquisite travelogue about Japan.

Barthes had fallen in love with Japan after his first visit in 1966. But he was the first to acknowledge that the “country I am calling Japan” was an imaginary country, and he was happy for the actual place to remain elusive. (As he confessed in a letter written in 1942, “I have no curiosity about facts, I am only curious—but fanatically so—about humans.”) Nothing pleased him more than the “rustle” of a language he did not understand: at last, language was freed from meaning, from the referential property that he called “stickiness,” and converted into pure sound. Not surprisingly, Barthes’s favorite contemporary artist was Cy Twombly, whose paintings resembled illegible scribbles—a style that Barthes, an amateur artist, emulated in his own drawings.

While Barthes learned a bit of Japanese, he had little interest in literatures other than French, and virtually none in French fiction written in former colonies such as Morocco, where he taught in the early 1970s and often spent his holidays, mostly in search of boys. (His loathing of colonialism did not extend to sexual tourism.) His taste in contemporary French literature ran to faddish practitioners of “neutral writing,” since his aversion to meaning left him indifferent to novels with psychological, much less historical, themes. He never wrote about Perec, the most innovative French novelist to emerge in the 1960s, who shared his fascination with language, writing, and the mythologies of consumer society. Perec was crushed by the “silence” of his “master,” insisting that his novels had “no other existence than those which your reading of them may provide.” But Perec was a Jew who had lost his parents in the war, and the void that lies at the center of his work is their disappearance in the Holocaust, not the satori, the emptiness of the haikus that Barthes adored. Perec’s novels were too “sticky,” too heavy with meaning for Barthes, who, as Sontag observed, “had little feeling for the tragic.”

Still, poststructuralism encouraged Barthes’s most appealing quality, the grain of his voice, and his writing increasingly assumed its own petite musique, liberal in its use of quotation marks, italics, and parentheses. At the time of Barthes’s defection from the structuralist camp, Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote him, “There is an eclecticism that comes across in the excessive liking you show for subjectivity, for feelings.” If Barthes was no longer capable of making distinctions between “symbolic forms” and “the insignificant contents that men and the centuries can pour into them,” perhaps, Lévi-Strauss speculated, structuralism had always been “far from his true nature.” Was the emperor of structuralist anthropology taking a jab at Barthes’s homosexuality, implying that he was too soft and feminine for the rigors of science? Perhaps, but he was not alone in expressing disdain for Barthes, whose autobiographical writings provoked frequent accusations of frivolousness or pandering among academics.

Barthes won election to the Collège de France by only a slender margin in 1975. Even Foucault, who had supported his candidacy, raised his eyebrows when, two years later, Barthes published A Lover’s Discourse. That book grew out of his obsessive love for a young Romanian man, an ordeal that led him to undertake an ill-fated analysis with Jacques Lacan (“an old fool with an old fogey,” as Barthes described their sessions). A delicate, often rapturous sequence of fragments about the many states of ardor, longing, and infatuation, it bathed unapologetically in the sort of rhetoric that Foucault had dismantled in the first volume of his History of Sexuality, published a year earlier.

But Barthes’s originality lay precisely in his riffs on ordinary experiences, which were met with glacial indifference, or smug dissection, from his peers. He democratized semiology by showing that we are all amateur semiologists when we are in love, obsessively reading the behavior of the beloved for signs of affection returned or denied. In his 1973 manifesto The Pleasure of the Text he defended another value held in disdain by “the political policeman and the psychoanalytical policeman.” He aligned himself with readers, with “the modest practices of a Sunday painter and an amateur pianist,” as Samoyault puts it, not with pedagogues, and winked at them knowingly, admitting that he, too, had a tendency to “boldly skip (no one is watching).”

The writers in Paris who best understood the anti-elitist thrust of Barthes’s late work were the novelist Philippe Sollers and his partner, the Bulgarian literary theorist Julia Kristeva, who edited the poststructuralist literary journal Tel Quel. They formed a strange triangle, as even Sollers—in his self-flattering words, “the only heterosexual man to have had the benefit of representing something for Barthes”—concedes. While Barthes was rhapsodizing about pleasure and desire, Sollers and Kristeva were cheerleading the Chinese Cultural Revolution, plastering the Tel Quel offices with the sayings of Chairman Mao. Barthes did not share their enthusiasm, but he was grateful for their friendship, and Kristeva’s convoluted theories about abjection made him feel “so inferior…so reduced to non-existence.”

In 1974, he joined them on an expedition to China. Barthes passed his time reading Bouvard and Pécuchet while Sollers played ping-pong with professors of Marxist philosophy. The puritanism of Mao’s China (a “Desert of Flirtation”) repulsed Barthes. “What can you know about a people, if you don’t know their sex?” he asked Sollers. He worried that he would have “to pay for the Revolution with everything I love: ‘free’ discourse exempt from all repetition, and immorality.” His diary of the trip, however, contained little criticism of Maoist China (Simon Leys called it “a tiny trickle of lukewarm water”). Barthes insisted that he was not “choosing” China, but “what the intellectual public wants is a choice: one was to come out of China like a bull crashing out of the toril in the crowded arena: furious or triumphant.” He had gone to China for the same reason that (in the face of considerable Parisian criticism) he had gone to lunch with President Valéry Giscard D’Estaing: “out of curiosity, a taste for hearing things, a bit like a myth-hunter on the prowl.”

By the early 1970s, Barthes was writing on what he called a “trapeze without any safety net, ever since I’ve no longer had the nets of structuralism, semiology or Marxism.” But being Barthes was more than enough, and for all his protests against meaning, he ended up producing some of French literature’s most moving writing on desire, love, and loss. The loss that affected him more deeply than any was that of his mother, who died in 1977, at eighty-four.

Barthes often spoke in his “Preparation for the Novel” lectures about Dante’s idea of the vita nuova, of starting out anew. But the thought of a new life without his mother was unfathomable to him. Although Barthes devoted much of his spare time to cruising, he was otherwise a strict monogamist: he lived his entire life, after all, with a single woman, who supplied him with an image of “the Sovereign Good.” Henriette Barthes was the one person from whom he scrupulously concealed his homosexuality, and one suspects that his reason had less to do with a fear of reproach than with a fear that she might mistake his other desires for infidelity. Her death left him almost paralyzed. When asked what he planned to teach the following semester, he replied, “I’ll show some photos of my mother, and remain silent.” Over the next year he took notes about his loss on more than three hundred index cards.

A number of the ideas in those index cards—published posthumously as Mourning Diary—were reworked in his last and greatest work, Camera Lucida, in which Barthes most fully realized his dream of “the novelistic without the novel…a writing of life.” Camera Lucida is a book about photography and mourning, and about how a single photograph allowed him to mourn Henriette’s death. Photography has usually been understood in relation to painting, but Barthes likened it, strikingly, to “a kind of primitive theater…a figuration of the motionless and made-up face beneath which we see the dead.” In a famous distinction, he argued that each photograph attracted our interest by way of two basic elements: the studium, “a kind of general, enthusiastic commitment,” and the punctum, a detail that “pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).”

On his desk as he wrote Camera Lucida was a photograph of five-year-old Henriette, in the winter garden of the house where she was born. It is the only photograph he discusses that is not reproduced in the book. “At most it would interest your studium: period, clothes, photogeny,” he writes. “But in it, for you, no wound.” The punctum in the winter garden photograph, for Barthes, is the “untenable paradox” of her character, “the assertion of a gentleness,” and it leads him to remember having “nursed her” while she lay dying, when she “had become my little girl, uniting for me with that essential child she was in her first photograph.” In one of the final images in Barthes’s work, Henriette, whose kindness permeated her son’s writing, is briefly raised from the dead, and Barthes, who was unable to go on after her death, achieves instead the miracle of birth: “I who had not procreated, I had, in her very illness, engendered my mother.” That Barthes, the most irreligious of French writers, left us with a vision of the immaculate conception was a paradox he might have savored.