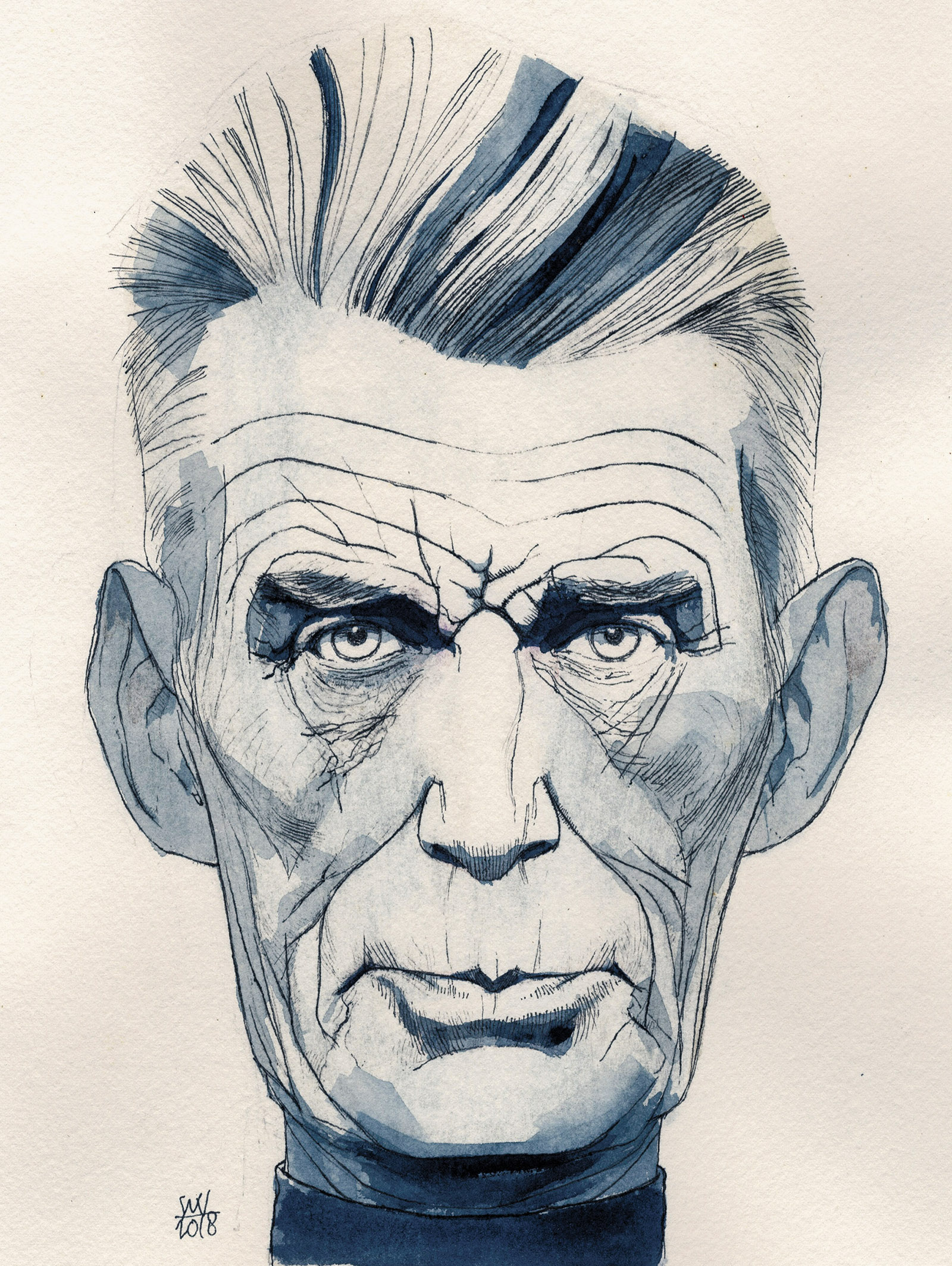

In April 1962, Samuel Beckett sent a clipping from the French press to his lover Barbara Bray: a report of the arrest in Paris of a member of the Organisation armée secrète. The OAS was a far-right terror gang whose members were drawn largely from within the French military. It had carried out bombings, assassinations, and bank robberies with the aim of overthrowing the government of Charles de Gaulle and stopping the concession of independence to Algeria. Among its targets had been Beckett’s publisher and friend Jérôme Lindon, whose apartment and office were both bombed by the OAS.

The press clipping detailed the capture of an army lieutenant who would be charged with leading an OAS attack on an arms depot outside Paris and a raid on a bank in the city. His name was Lieutenant Daniel Godot. Sending it to Bray was a typical expression of Beckett’s black humor. But it also serves as a reminder that his work is not an exhalation of timeless existential despair. It is, as Emilie Morin’s groundbreaking study, Beckett’s Political Imagination, shows, enmeshed in contemporary politics.

That such a reminder should be necessary is one of the more remarkable facts of twentieth-century cultural history. Beckett, after all, risked his life to work for the French Resistance, even though he was a citizen of a neutral country, Ireland. The astonishing works with which he revolutionized both the theater and the novel—Waiting for Godot and the trilogy of Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable—were written immediately after World War II and the Holocaust. Vladimir’s question in Godot, “Where are all these corpses from?,” and its answer, “A charnel-house! A charnel-house!,” hang over much of his writing. Torture, enslavement, hunger, displacement, incarceration, and subjection to arbitrary power are the common fates of Beckett’s characters.

Yet there is a long tradition of seeing him as not merely apolitical but antipolitical. In his introduction to The Complete Short Prose, for example, the brilliant Beckett scholar Stan Gontarski writes:

The focus of injustice in Beckett is almost never local, civil, or social, but cosmic, the injustice of having been born.

Deirdre Bair, in her pioneering 1978 biography of Beckett, called him “consistent in his apolitical behavior,” claimed that politics was “anathema” to him, and described him as having “walked away from any conversation that veered into politics.” For the English left-wing playwrights of the 1960s, he was a disengaged pessimist with nothing to contribute to political discourse except a disempowering despair. In France, Maurice Blanchot’s early advocacy of Beckett as (in Morin’s summary) the creator of “a narrative voice divorced from recognizable political and historical parameters” established an enduring template. Another of his great advocates, Theodor Adorno, happily conceded that “it would be…ridiculous to have him testify as a key political witness.”

On a superficial level Morin, in her richly illuminating study, shows more comprehensively than anyone else has the plain untruth of the notion of a Beckett who walked away from any political conversation. He was an avid reader of left-of-center newspapers: Combat and Franc-Tireur in the 1940s, L’Humanité and Le Monde thereafter, Libération in the 1980s. While he was described in The Observer in 1969 as a man who had only ever signed one petition—against the poor regulation of French slaughterhouses—he actually signed dozens, from support for the Scottsboro boys (black teenagers falsely accused of raping white women in Alabama) in 1931, when he was twenty-five, all the way to a denunciation of the Iranian fatwa against Salman Rushdie in 1989, the year of his death. Although the only political party to which he donated directly was the African National Congress—he adamantly refused to allow his work to be performed before segregated audiences in South Africa—he endorsed a public appeal to vote for the Socialist Party in the 1986 French parliamentary elections and ensured that his Polish royalties were distributed through the trade union Solidarity to the families of imprisoned dissidents. He dedicated his late play Catastrophe to Václav Havel, who was then in prison in Czechoslovakia, and he donated valuable manuscripts to Amnesty International and Oxfam.

Beckett was always politically aware. In Dublin in the 1930s, he associated (in spite of his impeccably Protestant and Unionist family background) with the members of the small leftist fringe of Irish republicanism—Charlie Gilmore, Peadar O’Donnell, and Ernie O’Malley. One of the more startling revelations from the splendid Cambridge edition of Beckett’s letters was his deeply serious attempt to move to Moscow in 1936 to study cinematography with Sergei Eisenstein. He did succeed in traveling to Hitler’s Germany, where he lived between September 1936 and April 1937, and his up-close study of Nazi propaganda is a strong influence on his later work. And of course, he chose to return from the safety of Dublin to Nazi-occupied Paris, where he became an important member of the underground cell Gloria SMH. In 1977 Richard Stern asked Beckett whether he had ever been political. The reply—“No, but I joined the Resistance”—is one of his typical self-canceling sentences, in which the second part utterly negates the first.

Advertisement

Beyond these biographical facts, though, Morin demonstrates how Beckett’s writing was engaged from early on with questions of colonialism, power, and race. She pays particularly acute attention to his work in translating the French texts for Nancy Cunard’s landmark 1934 anthology Negro, which brought together writings from Africa, Europe, and America to create the sense of a global anti-imperialist and antiracist current connecting French and British colonies to the Négritude movement in Paris and the Harlem Renaissance in New York. Beckett, in his contemporary letters, tended to be defensive and disparaging about this work, suggesting that he was a mere jobbing hack, glad to receive “a few quid anyhow” from Cunard. But Morin shows conclusively that he was in fact deeply engaged with it, even intervening to emphasize in his translations political points that are more obscure in the original texts. At the very least, the work gave Beckett a crash course in the languages of racial oppression and resistance. It is notable that the only poem of his to have a dedication in the text is “From the Only Poet to a Shining Whore. For Henry Crowder to Sing.” Crowder, a jazz musician and Cunard’s lover, was African-American.

Indeed, Morin’s superbly researched book is so convincing in its meticulous recreation of Beckett’s political worlds that it raises an entirely new question: Why, given all of this immersion in oppression, propaganda, totalitarianism, colonialism, and racism, is Beckett’s artistic work not more explicitly engaged? Why does someone who knew so much and cared so deeply about history and politics create a body of work in which they are approached so obliquely? There are some obvious answers—one biographical, the other aesthetic—but they are not entirely adequate.

The biographical one is that Beckett was always a displaced person. He was a Protestant in a self-consciously and at times aggressively Catholic Irish state. Subsequently he was an alien in France. He is so strongly associated with Paris that it is hard to remember that he always held and renewed what he called his “green Eire passport,” and joined the other migrants and strangers in the lines at immigration services to renew his residency permits. As a mature writer, Beckett never lived in the country of his citizenship and was never a citizen of the country he lived in. He did not feel entitled to criticize the governments of either Ireland or France directly. He also knew—especially during the fraught years of the Algerian war when the French government was cracking down on dissent—that he could be deported at any time.

The aesthetic reason is that Beckett was no good at writing history plays or political satires and had no interest in realistic fiction. He did try: there are intriguing vestiges of an abandoned satirical history of Ireland called Trueborn Jackeen, and he attempted, while in Nazi Germany, a historical drama about Samuel Johnson. But he had grown up as a writer directly in the shadow of his friend and idol James Joyce, who had done pretty much everything that could be done with the novel of social and psychological omniscience. To escape Joyce’s magisterial grandeur, Beckett had to find his own voice in ignorance and inadequacy—qualities that do not lend themselves to political and historical statement.

These are good reasons but they are not sufficient. Beckett could, after all, have taken French citizenship: as a decorated war hero (awarded both the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille de la Reconnaissance Française) he would hardly have been refused. And writers of far lesser talent managed well enough to carry on in the existing forms of drama and fiction after Joyce. To really understand the relationship between Beckett’s politics and his work we have to return precisely to the notion that Adorno described as “nonsensical” and “ridiculous”: the idea of Beckett as witness. But we have to return to it in a very particular way, for Beckett is above all witness to what he is not: not a Jew, not tortured, not deported to a concentration camp. His work is ultimately defined by the things that nearly happened to him but did not. He escaped the worst but never got over it. Vladimir’s questions—“Was I sleeping, while the others suffered? Am I sleeping now?”—haunted Beckett himself.

To say that Beckett was not Jewish may be merely to state the obvious, but this was not in fact obvious at all. In 1937 W.B. Yeats wrote to his friend and muse Dorothy Wellesley a letter that was pointedly not included in their later published correspondence. He told her of a libel trial about to open in Dublin, in which his friend Oliver St John Gogarty was being sued by Harry Sinclair, whose recently deceased brother William was married to Beckett’s aunt Cissie. Gogarty was a virulent anti-Semite (a fact that has significant bearing on Joyce’s Ulysses, where he appears as Buck Mulligan). The Sinclairs were Jewish. In his fictionalized memoir, As I Was Going Down Sackville Street, Gogarty applied to the Sinclair brothers—whom he called, rather obscurely, “twin grandchildren of the ancient Chicken Butcher” without naming them—the full range of anti-Semitic slurs, beginning with usury and rising to pedophilia. Harry Sinclair sued, and Beckett agreed to give evidence, crucial in a libel trial, that he recognized the Sinclairs from Gogarty’s disguised references. Yeats wrote to Wellesley of Gogarty that

Advertisement

In his book he has called a certain man a “chicken butcher,” meaning that he makes love to the immature. The informant, the man who swears that he recognised the victim[,] is a “racketeer” of a Dublin poet or imatative [sic] poet of the new school. He hates us all…. He & the “Chicken Butcher” are Jews.

This identification of the young Beckett as a Jew and a “racketeer” who “hates us all” had consequences. Yeats had considerable influence with the only newspaper that printed Beckett’s work, The Irish Times. It pulled Beckett’s review of Yeats’s Oxford Book of Modern Verse. It published instead a piece by Yeats’s close ally the poet F.R. Higgins, in which, without being named, Beckett was associated with another typical anti-Semitic slur, that of rootless cosmopolitanism—“our literary birds of passage—the cosmopolitans—of no racial abode, of no background.” Higgins also echoed Yeats’s description of Beckett as a racketeer, complaining of the “insecure slickness, so negative and, [sic] unmanly…promoted by those cultural racketeers.” Added to the trauma of the libel trial, in which he was labeled by Gogarty’s barrister a “bawd and blasphemer from Paris,” these attacks convinced Beckett that he had no future in Ireland. He was not a Jew but he was Jew-ish, close not only to the Jewish circles around Joyce, to the Sinclairs, and to the Dublin Jewish intellectual Con Leventhal, but to the intolerable condition of lacking a “racial abode.”

Just as Beckett came close to being Jewish, he also came close to the concentration camps. When the Gloria SMH cell was betrayed to the Nazis in August 1942, he and his partner, Suzanne Déchevaux-Dumesnil, escaped only because they were able to flee before the Gestapo came for them. Twelve members of Gloria SMH were shot, and a further ninety were deported to Ravensbrück, Mauthausen, or Buchenwald, often after torture in France. One of them, Beckett’s close friend Alfred Péron, with whom he played tennis and worked on translating his novel Murphy into French, survived Mauthausen only to die of exhaustion and malnutrition on his way back to France from the camp.

These near misses placed Beckett in a strange position—he was too close to the horrors not to write about them but too distant to write of them with personal authority. He had survived to tell a tale, but it could not be the tale of a survivor. The great achievement of Morin’s book is to plunge Beckett’s works back into the immediate literary setting in which they appeared, which was Lindon’s list at Éditions de Minuit. A large part of Lindon’s mission was to document atrocity, to make available accounts of the Vichy regime, the Nazi occupation, the deportations, and the camps, and later of the use of torture by the French in Algeria. During the latter conflict, between 1958 and 1962, nine books published by Éditions de Minuit were seized by the French authorities, who were determined to suppress the truths they were telling. It was Beckett who lent Lindon the money to keep the imprint going in the face of this onslaught. Lindon, moreover, explicitly linked his partnership with Beckett to his work in documenting atrocities:

I am Samuel Beckett’s publisher: to have this chance and this honour is to benefit from an extraordinary freedom in a free country, and the least that can be done is to defend the conditions of this freedom when they are under threat.

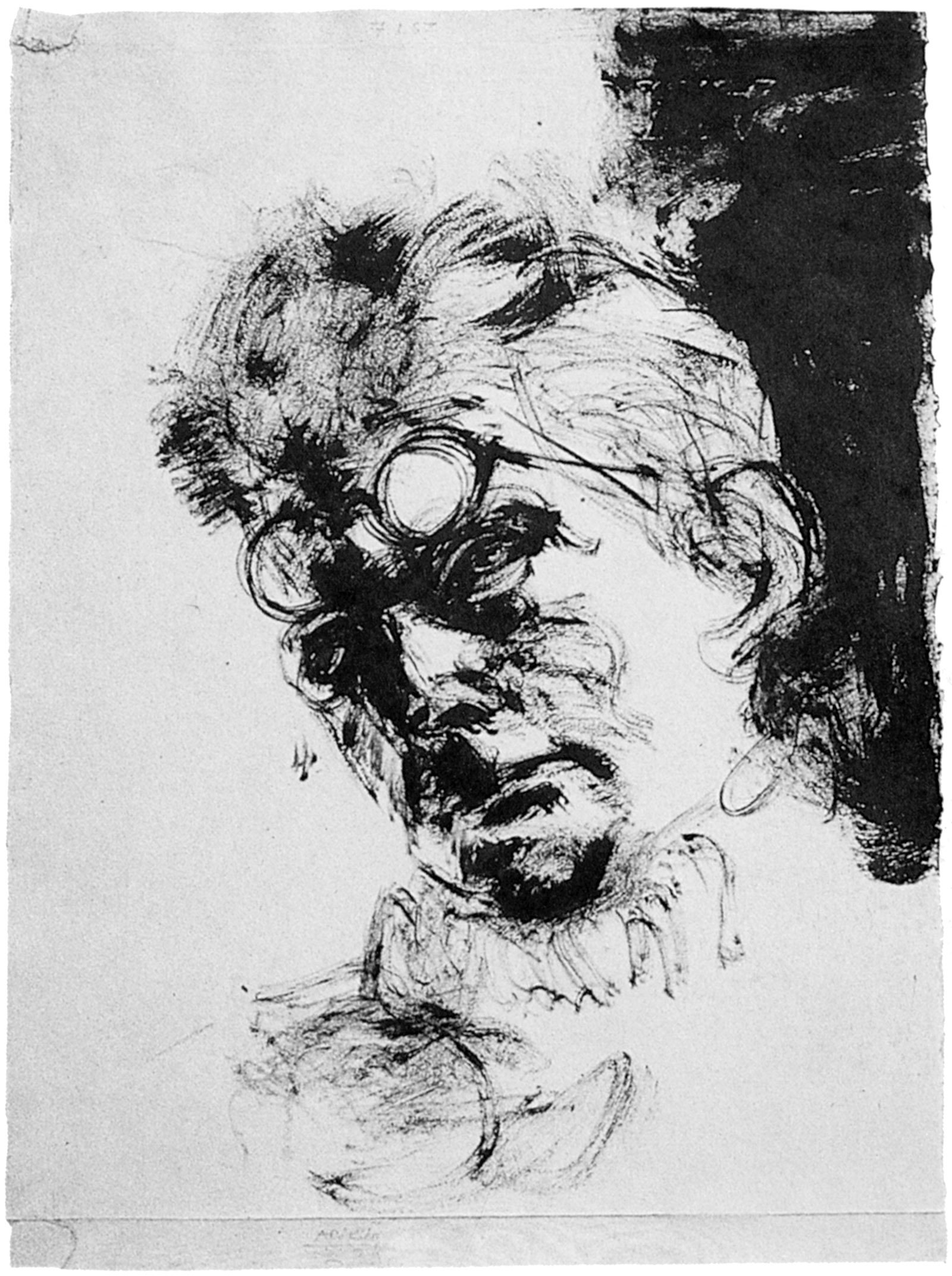

Beckett’s work thus appears as part of a larger exercise of witness. Yet what, after all, had he witnessed? Nothing that greatly mattered when placed beside, for example, the experiences of one of his closest friends in postwar Paris, the painter Avigdor Arikha, whose first drawings were of beatings, corpses, and gravediggers’ tools in the Jewish ghetto and labor camp Mogilev-Podolsk. Famously, in his dialogues with Georges Duthuit, published in 1949, Beckett spoke of the need for a new kind of art characterized by

the expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express.

We might, however, reformulate this with regard to the question of witness. Beckett was not a Jew. He had merely had a tiny taste of the poison of anti-Semitism. Beckett had not directly experienced torture at the hands of the Gestapo or deportation to a concentration camp. He had merely experienced these things indirectly, through the fates of his friends and through basic human compassion. He was left therefore with a paradox: the need to express what he had not experienced, to be a witness to what he had not seen. His art would come from having no power to witness, no desire to witness, no authority as a witness—together with the absolute obligation to witness.

If the literature of witness is driven by the need to say what has been seen, Beckett’s ethical response to his particular dilemma is (to adapt one of his late titles) to ill say what he has ill seen. He cannot write about anything—he told Duthuit that he was “no longer capable of writing about.” He must provide instead a photographic negative in which everything is reversed. Where testimony recreates what happened, Beckett can instead only try to create in words some correlative to the thing itself, the stripping away of humanity, the utter powerlessness, the confusion, the oblivion, the arbitrariness, the almost complete loss of the known world.

To the basic demands of documentation—who? what? where?—Beckett provides only the unnameable person, the unknown purpose, the landscape of nowhere. Witness is autobiographical, but for his characters the biographical journey from birth to death cannot function: “Birth,” as A Piece of Monologue has it, “was the death of him.” He cannot even offer the consolation that at least what has happened is being properly remembered because he has no authority to remember. When Vladimir tries to recall even the beginning of the evening, Estragon interjects: “I’m not a historian.” In the face of the urgent need to recollect the dead and how they died, Beckett writes, in the immediate postwar story “The Expelled”:

Memories are killing. So you must not think of certain things, of those that are dear to you, or rather you must think of them, for if you don’t there is the danger of finding them, in your mind, little by little. That is to say, you must think of them for a while, a good while, every day several times a day, until they sink forever in the mud. That’s an order.

Literature gives shape to experience, but Beckett understands that, seen from the abyss, there is no shape to history. The powers that be are feral, their authority terrifying in its arbitrariness. In Godot, there is a nameless, unseen “they” who might be policemen or militia or vigilantes on the lookout for vagrants exactly like Estragon and Vladimir. Between the two acts of the play, in that blank dramatic space whose very emptiness resonates with Beckett’s aesthetic, Estragon has been attacked by a gang of ten men and Vladimir’s questioning of him takes us into the psychology of those who are subject to arbitrary power, their desperate hope that there is some formula of behavior that will deflect its cruel caprice:

Estragon: I wasn’t doing anything.

Vladimir: Then why did they beat you?

Estragon: I don’t know.

Vladimir: Ah no, Gogo, the truth is there are things escape you that don’t escape me….

Estragon: I tell you I wasn’t doing anything.

Vladimir: Perhaps you weren’t. But it’s the way of doing it that counts, the way of doing it, if you want to go on living.

The landscape through which Molloy moves is haunted by nameless manhunters, tracking down those “worthy of extermination.” Molloy matter-of-factly advises us:

Morning is the time to hide. They wake up, hale and hearty, their tongues hanging out for order, beauty and justice, baying for their due. Yes, from eight or nine till noon is the dangerous time. But towards noon things quiet down, the most implacable are sated, they go home, it might have been better but they’ve done a good job, there have been a few survivors but they’ll give no more trouble, each man counts his rats. It may begin again in the early afternoon, after the banquet, the celebrations, the congratulations, the orations, but it’s nothing compared to the morning, mere fun…. Day is the time for lynching, for sleep is sacred, and especially in the morning, between breakfast and lunch.

The use of “lynching” here reminds us of Beckett’s immersion in the realities of racial oppression in the US going back to the early 1930s. It also points to the potency of his negative method of bearing witness. Molloy is not being beaten or tortured or murdered. He is hiding, evading—and the passage is all the more terrible for that. It evokes everything by describing almost nothing.

The general imperative of the immediate post-Holocaust years was factual precision about what took place, and Beckett can be seen in this light as culpably evasive. But precisely because it relates to nowhere in particular, this passage can relate to anywhere, to pogroms and lynchings, to Babi Yar or Rwanda or Bosnia or Alabama, or Rakhine State, to Jews or Tutsi or Muslims or Rohingyas. Equally, the strange architecture of confinement in an apparently obscure work like The Lost Ones (“One body per square metre…or two hundred bodies in all round numbers…. The gloom and press make recognition difficult”) may recall the literature of the concentration camps, but it could be any gulag or slave ship. And the torture chamber in the late play What Where, with its repeated injunction “Give him the works,” may be inspired by the French in Algeria, but it exists all over the world.

This is the most political thing about Beckett: because there is no fixed time or space, there are no comforting boundaries, no historical moments into which we can pack away all the trouble and then move on. The entirely understandable impulse after great horror is to think that at least it is over. It can be documented because it is finished. The literature of witness is an attempt to fix the immediate past, but in Beckett the horror is not past. In Beckett there is only one tense, the present. There is only the voice speaking endlessly in the darkness, speaking to us now. The dead cannot be remembered because they are not even dead. They exist, as the opening line of The Lost Ones has it, in an “abode where lost bodies roam each searching for its lost one.” Much as we like to think otherwise, politics is always such an abode.

This Issue

June 7, 2018

The Afro-Pessimist Temptation

Moving Targets