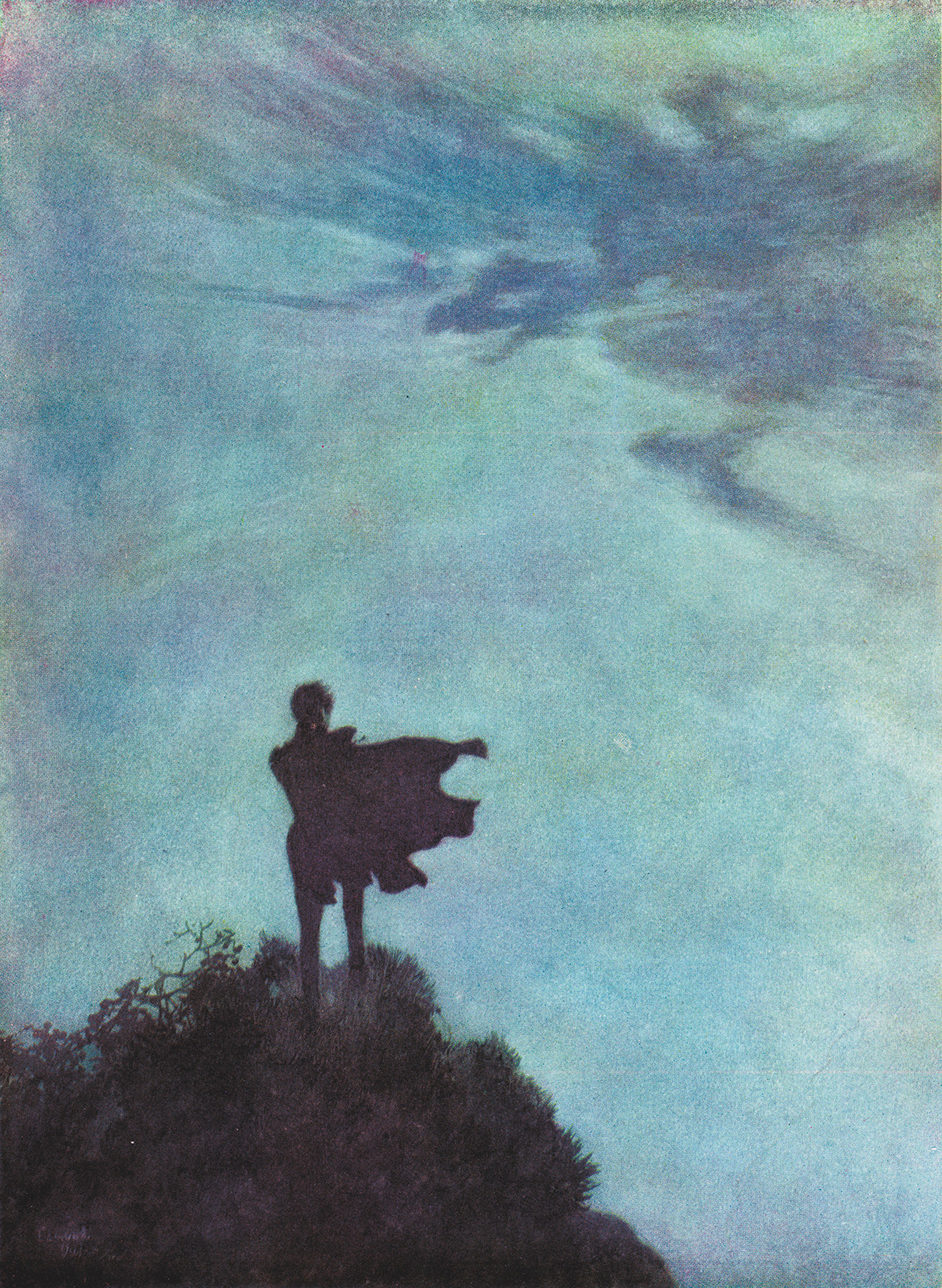

Proust remarked about Stendhal that he may have used rudimentary and banal descriptions but that he lights up when he pinpoints an elevated place, such as Fabrizio del Dongo’s and Julien Sorel’s prisons or the Abbé Blanès’s observatory, in which the characters cast aside their cares and take up a “disinterested voluptuous life.” Julien Gracq’s descriptions are wonderfully worked, but if he had a characteristic and favorite place in which to situate his action, a place that excited all his creative powers, it would be the seashore enveloped in fog. His world is one of decaying grandeur, palaces reverting to mold and swamp, mud-silted battleships, official inertia, the odor of stasis when “the familiar rotting smell passed over my face like the touch of a blind hand.” Fog and moonlight are what might be called the emblems of his fiction.

In a 1959 essay about the mysterious German writer Ernst Jünger, perhaps his major influence, Gracq said of Jünger’s 1939 novel On the Marble Cliffs that it is “an emblematic book” rather than a livre à clef or an “explanation of our period.” Gracq prefers to invoke the lore of heraldry, images drawn from our life but resistant to interpretation, chess pieces that “burn the fingers” just to touch. Writing about On the Marble Cliffs, Gracq could be describing one of his own novels: “We could call it a symbolic work but only on condition of admitting that the symbols can only be read as enigmas seen in a mirror.” Nothing is autobiographical or political; everything is mythic.

Julien Gracq was the pen name of Louis Poirier (1910–2007). He took the first name from Julien Sorel of The Red and the Black, his favorite Stendhal novel, and the last name from the Gracchi, the ancient Roman brothers who defended the rights of the poor. In a passage from 1980 imagining the complete surprise that the French Revolution represented for the people of the day, he quoted a line from the Roman satirist Juvenal: “Who could endure the Gracchi railing at sedition?”

Gracq grew up in Saint-Florent-le-Vieil, near the mouth of the Loire and twenty-two miles from Angers in western France. He studied in Paris and became a friend of “the pope of Surrealism,” André Breton, who hailed his 1938 novel Château d’Argol as the first Surrealist novel, though the Surrealists took a dim view of most novels. Gracq himself thought of Surrealism as less a movement than a way of practicing poetry, a “dynamic, active search for all the paths and all the methods leading to a poetic state.”

As a soldier during World War II Gracq was captured and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp in Silesia. After the war he taught history and geography in a lycée in Paris for twenty years; he studiously avoided publicity and thrice refused to dine with French president François Mitterrand, and he rejected the Goncourt Prize. He never married, though his writing makes it obvious that he was a lover of women; after his retirement he returned to Saint-Florent-le-Vieil, where he lived with his sister.

Gracq wrote only a handful of novels, each one dense and richly wrought. The first one, Château d’Argol, distinctly recalls Edgar Allan Poe, whom Gracq considered a writer that Americans from the land of “the cow catcher” and “the redskin” completely misunderstood and who was fully embraced only by Europeans, who knew how to appreciate “these immemorial colors” and “this delirious and funereal majesty.” The action in his novel, such as it is, comes out of the same universe as “The Fall of the House of Usher”; in Gracq’s hands it is set in a seaside castle next to a windy (and of course foggy) seaside forest. Two men, friends and rivals since childhood, and the mysterious, witchy woman one of them introduces, are virtually the only characters. Murder and suicide ensue, but the plot is insignificant next to the long, “decadent” sentences, the seemingly random but menacing words cast into italics, the remarkable unity of place, the use of all those adjectives creative writing classes forbid: implacable, unbelievable, incomparable—words that Joseph Conrad also relied on and that announce that the writer has been defeated in his attempts to describe the (what else?) ineffable.

Château d’Argol, like Poe’s stories, emphasizes the landscape as the dark sublime. The characters are static. Everything, from start to finish, is moving toward death, and the prevailing mood is one of terror or doom. Words repeat as in Poe: “In the very middle of the long December night, down the deserted stairs, through the deserted rooms where the candles were burnt out, where the candles were overturned, he left the castle in a traveller’s attire.” Compare Poe’s “Ulalume”: “The leaves they were crispéd and sere—/The leaves they were withering and sere” or “As the scoriac rivers that roll—/As the lavas that restlessly roll.” All the poetic props are in Poe: the “lonesome October,” the “most immemorial year,” “the ghoul-haunted woodland,” as well as demons and mist. In Gracq there are “meshes of mist” and “unavowable bonds.” Then there is this characteristic passage:

Advertisement

And nature, restored by the fog to its secret geometry, now became as unfamiliar as the furniture of a drawing-room under dust-covers to the eye of an intruder, substituting, all at once, the menacing affirmation of pure volume for the familiar hideousness of utility, and by an operation whose magical character must be evident to anyone, restoring to the instruments of humblest use, until then dishonoured by all that handling engenders of base degradation, the particular and striking splendour of the object.

This contempt for anything useful, this admiration of transforming difference, is not so far from Huysmans’s Against the Grain, nor is the comparison of nature to the furniture in a salon draped in Holland cloth.

Gracq’s second novel is difficult, starting with its title. In English it is called A Dark Stranger, but in French Un beau ténébreux has richer connotations—“a handsome man” who is “gloomy,” or “dark” or “mysterious” or “shadowy,” derived from tenebrae, in Latin a holy office preceding Easter during which the lights are turned off one by one to signify Christ’s death. In this case, the beau is Allan, a rich young man, half-French and half-English, who comes to an elegant seaside hotel in Brittany and has soon become the obsession of all the other guests, members of la jeunesse dorée. They are so obsessed that they are unable to leave the summer resort at the close of the season or well into the autumn. The mood of the book is sounded from the very beginning:

Sand drifted across the dunes, the air snapped like great banners, standing up against the cutting edge of the wind with a feline flick of the tail. And out on the horizon the hurried toing and froing of the waves, always this commotion of foam, this riotous churning, a confusion of clouds lined with squalls and sunshine, this fierce train of swells, the unfailing impatience of the sea in the background.

In his wonderfully inventive and totally original literary criticism, Gracq praises the “slowness pills” that the novel ideally administers. He admires “narrative pauses” that fulfill the function “of an organized delay, a braking in the action, whose goal is to let all the reserves capable of orchestrating and amplifying it flow towards the dramatic apex already in view.” A Dark Stranger is constructed out of such organized delays. We know that Allan is self-destructive and half in love with death; we guess through heavy foreshadowing that the end of the book will be his suicide. But we take a long, foreboding path to get there.

For one thing, Allan is a compulsive gambler. He plays for ruinous stakes that would destroy any fortune, no matter how great. The other gamblers look on as he loses—“and, offensively, impertinently, mercilessly, he was taking his time over it, arranging it in clever stages, removing the veils of benign, bland, mollifying assumptions one by one and standing upright in the unbearable and now indisputable nakedness of scandal.” There is something theatrical, indeed tragic, in Allan’s headlong course toward death. (Gracq wrote plays and translated Kleist’s great play Penthesilea, about an Amazon queen in conflict with—and in love with—Achilles.) Another of the novel’s characters, a young man named Gérard Kersaint, challenges Nietzsche’s view of tragedy as founded on the passions; he argues, however, in an entry from his diary,

that somewhere in the plot there’s always an unjustifiable urge in one of the characters, a sudden inspiration as violent as a change in the wind, which deep down can’t be justified by any motive…. A form of holy madness, an infectious state of trance, a solstice bonfire that spreads from one character to the next.

The first 180 pages of A Dark Stranger are leaves from Kersaint’s diary like these reflections on tragedy. He’s an intellectual, ruminating on Molière, Chateaubriand, and Baudelaire. The owner of the hotel tells Gérard that he’s worried about Allan, who deposited a vast sum of money in the hotel coffers and now has spent half of it, as if the charismatic young heir wants to die penniless. Gérard runs into his friend and says, “You frighten me, Allan. I’ve sensed it since I’ve been here: you’re on the brink of something irreversible.”

Gérard brings up a young woman, Christel, who is in love with Allan and seems likely to follow him into death. Gérard asks Allan if he feels he has the right to take on this somber part, focused as Christel is on his tragic destiny, something “which isn’t focused solely on you as a person—but on some revelation beyond you.”

Advertisement

“And why not?”

“Fine I don’t think I’ve got any more to say to you.”

We left each other in a heavy silence.

On September 1 the guests stage a fancy dress ball, which people call “the party with no tomorrow.” Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death” comes to mind. Everyone is nervous and excited, as they wouldn’t be with a normal party. Allan and Dolorés, his date, are costumed as suicidal lovers out of a poem by Alfred de Vigny, each with a bloodstain over the heart. When Gérard stops to talk to Dolorés, she says, “At a dance like this it’s easy to take yourself for a god paying an incognito visit to the world in your grey cloak.” She also tells him that whereas death for most people is the end, for others it might be a “vocation.”

As dawn approaches at the end of the party, the guests feel that something is about to fall apart. With the autumn’s first frost “it was as if they’d suddenly been transported to the wardroom of a ship trapped in winter ice floes.” The hotel emptied of most of its guests is like a “body drained of its lifeblood and commotion.” Page after page the imagery becomes relentlessly funereal: “The extraordinary stillness of the moon sucked the life out of this dark sombre room through the windows, as an embalmer drains a skull through the nostrils.” Would Gracq have been so in control of this morbid language if he hadn’t been sensitized by the Surrealists?

Christel barges into Allan’s room: “The pallid face crouched beneath the heavy dark hair like a crime in the depths of a darkened house” (is this what Freud would call “displacement?”). Suddenly she says accusingly, “You’re going to die. You want to die, I know it. I’ve known for days, weeks.”

After demurring for a moment, Allan confesses, “It’s true, Christel. This is my last night.” When she tells him that she loves him, he replies, “You love me, but only mingled with my death.” Such a Byronic hero could be maddening, but due to Gracq’s elegant indirection and strategic pauses the text is so suspenseful (we know what is going to happen but not when or how) that it never becomes predictable or pretentious.

A Dark Stranger observes the classical unities (well, two months but one place and a restricted cast of characters and a single situation). That and the central premise make it feel avowedly theatrical. Why write such a book? It came out in 1945 but is set in the pre-war period; it expressed the anxiety of 1945, but also the vague hopes and fears of rich idlers in 1939. No one knew exactly what would happen at that time, but the future seemed tragic and inevitable.

Gracq alternated between realistic novels and mythical ones. The Opposing Shore may be a masterpiece, but to my mind it’s a botched one, like Nabokov’s Ada—admirable, fertile as a subject of reverie, totally tedious. In both cases we are in a made-up land, and the plot involves a love affair that has been nourished on archetypal romances. In The Opposing Shore the country, Orsenna, may be something like Venice with its dated but institutionalized customs. Its long-standing enemy, Farghestan, with which it has been in a hazily defined state of dormant war for three centuries, may be something like the Ottoman Empire. The plot concerns a young aristocrat, Aldo, who is sent to a naval base on the Farghestan border. After endless, almost Jamesian dithering and the steady if oblique opposition of Marino, his commander, Aldo finally goes over to the opposing shore, to Farghestan.

Marino argues that it would have been better to leave Farghestan unknown and to keep Orsenna “a land where it’s good to lie down and go to sleep.” Only an accomplished poet and utterly civilized man such as Richard Howard could have translated this dialogue spoken by articulate but devious hysterics, this narrative so rich in evasions, and these Proustian sentences:

The intimate feeling that had drawn taut the thread of my life had been that of an ever deeper aberration; starting from the broad ways of childhood, when all of life closed over me like a warm embrace, it seemed to me that gradually I had lost contact, turned away with the passing days toward ever more solitary roads where at times, disoriented, I stood still a moment and caught no more than the brief and lonely echo of a nighttime street emptying of all traffic.

Baffling as these abstractions and metaphors might be, we feel they might make sense if we only concentrated harder. They don’t seem to repel meaning, just resist it. This novel is full of mist and moonlight, old men “ill-defended against a long memory,” and we learn that the harbor of Sagra

was a baroque marvel, an improbable and disturbing collision of nature and art. Very old underground canals, between their disjointed stones, had ultimately managed to spew through the streets the waters from an underground spring which they had brought from leagues away; and slowly, with the centuries, the dead city had become a paved jungle, a hanging garden of wild trunks, a frenzied gigantomachia of tree and stone.

Although The Opposing Shore is worlds away from A Dark Stranger in its pacing, both are about attractive young men who are drawn toward a catastrophic act. In Balcony in the Forest, Gracq’s last and best novel, the catastrophe happens to Lieutenant Grange and his men as they wait through the “phony war” in 1939 for the real war to begin. First published in 1958, two decades after the time described, it is again full of sea-girt forests and mist, but this time the telling is the most realistic Gracq ever managed.

The lieutenant, we learn, is “a great Poe enthusiast.” The jerry-built fortresses and bunkers are already subject to “rust and ruin,” well before the actual fighting. Living with a handful of soldiers, whom he mostly likes, the lieutenant is no shirker but he doesn’t want to “participate” with total conviction—though in this case his reluctance is not some metaphysical rejection, just a temperamental disinclination. Now the poetic images are much more muted, more ideographs than elaborated metaphors: “He fell asleep, one hand hanging out of his bed over the Meuse as if across the gunwale of a boat: tomorrow was already very far away.” His men come down the stairs for a first inspection, “clumsy, circumspect, and squinting like suspicious Berber tribesmen.” In the small rooms Grange’s “feeling of confinement became oppressive: his body moved here like the dry kernel inside a nutshell.”

This is what is called sensible, masculine writing, an Englishman’s writing, such as Graham Greene’s. Nothing embarrassing or over-the-top. The stagnant conflict was “a curtain accidentally dropped by a remote stagehand at the play’s most exciting moment.” Although the sentences can be long, they no longer teeter on the edge of the incomprehensible: “The air was soft and warm, heavy with the smell of plants.” Further on:

The night protected him, gave him this easy breathing and this prowler’s freedom of movement, but it was the night that brought the war closer: as if a fiery sword were writing great pure characters above the world that cowered in primordial fear; roused, the sky over the woods watched dark France, dark Germany, and between the two the strange, calm scintillation of Belgium, whose lights died away at the horizon’s edge.

Richard Howard masterfully renders the crescendo of the fiery characters and the rumbling diminuendo of the last phrase—thunder after lightning.

Fed up with the preening, “carefully groomed” soldiers in town, with their womanizers’ soft gaze (“like officers during the Dreyfus Affair”), Grange wanders the Ardennes forest, where he chances upon a young woman whom he dubs “a rain-sprite.” She pays no attention to him, “like a kitten that ignores you for a ball of string.” Suddenly she wants to walk with him (“It’s more fun”). He asks her if she, improbably enough, is vacationing here, and she responds, “Oh no!… I’m a widow,” and with childish glee announces, “I have a family ration book!”

Mona and Grange become lovers; she is as antic and supernaturally wise as Pearl in The Scarlet Letter, as warm as an “unmade bed.” She “lived and grew against him like a tree espaliered on a wall.” Their affair has no future, and one day she simply disappears.

To a remarkable degree, Balcony in the Forest seems distinctly conscious of moments of being, the startled, inconsequential, unmotivated awareness that we exist, are living—and living now: “How dense, how concrete the present became, in her shadow. With what force of conviction, with what energy she was here!” After more endless waiting for battle, these are Grange’s thoughts:

It was as if everything were dissolving under his eyes, disappearing, cautiously evacuating its still intact appearance down the cloudy, sluggish river, and desperately, endlessly going away—going away.

As the waiting continues,

Perhaps for the first time, Grange told himself, he was mobilized in a dream army. “I’m dreaming here—we’re all dreaming—but of what?” Everything around him was anxiety and vacillation.

Using one of his newly spare, chthonic images, Gracq writes: “The earth was like a dog showing its teeth.” When the war finally begins: “‘The forest,’ he thought again. ‘I’m in the forest.’ He couldn’t have said anything more than that: it was as if his mind were yielding to a better kind of light.” This ecstatic apprehension of existence may have been Gracq’s most powerful gift. For the last three decades of his life Gracq wrote travel books and criticism, but no fiction.

This Issue

June 28, 2018

It Can Happen Here

Danse Macabre

Brave Spaces