A museum dedicated to memory and human rights was on nobody’s agenda when the Chilean people managed, after almost seventeen years of dictatorship, to restore democracy to their country in 1990. More urgent tasks awaited. A military government led by General Augusto Pinochet had ruled Chile since the democratically elected president, Salvador Allende, was overthrown in 1973. Throughout its years in power, Pinochet’s government not only engaged in gross violations of human rights—mass executions, torture, exile, imprisonment without trial, raids on shantytowns where the men were rounded up and stripped naked in the rain while the women and children watched—but also systematically suppressed evidence of its crimes. This was done so effectively that, by 1990, over 40 percent of the population still fervently supported the outgoing regime and believed that the supposed horrors of the Pinochet era were fabricated by left-wing propaganda outlets. The country’s priority, therefore, was to establish the facts and unite the nation—including many of Pinochet’s misguided enthusiasts—behind a true account of what had happened.

This was achieved in 1990 and 1991 through a Truth and Reconciliation Commission dealing with cases of death and disappearance. It was followed years later, in 2003 and 2011, by two other commissions that dealt with survivors who had been tortured (almost 40,000 proven cases) and offered them various forms of reparation.1 Gradually the courts—cravenly subservient during the dictatorship—found ways to circumvent the Pinochet amnesty laws that exempted state agents from prosecution. Scores of the most notorious perpetrators were sent to jail, albeit to a luxury prison specifically built for them.2

These steps did not, however, address a troubling problem: What of the innumerable locations all over the country where terror had been inflicted, and that were in danger of being forgotten, erased, or normalized? Under pressure from human rights organizations, many of those places became officially protected as part of Chile’s patrimonio,3 but this process was haphazard and scattered; it quickly became clear that the task of preservation ought to be centralized and its results lodged in a permanent home.

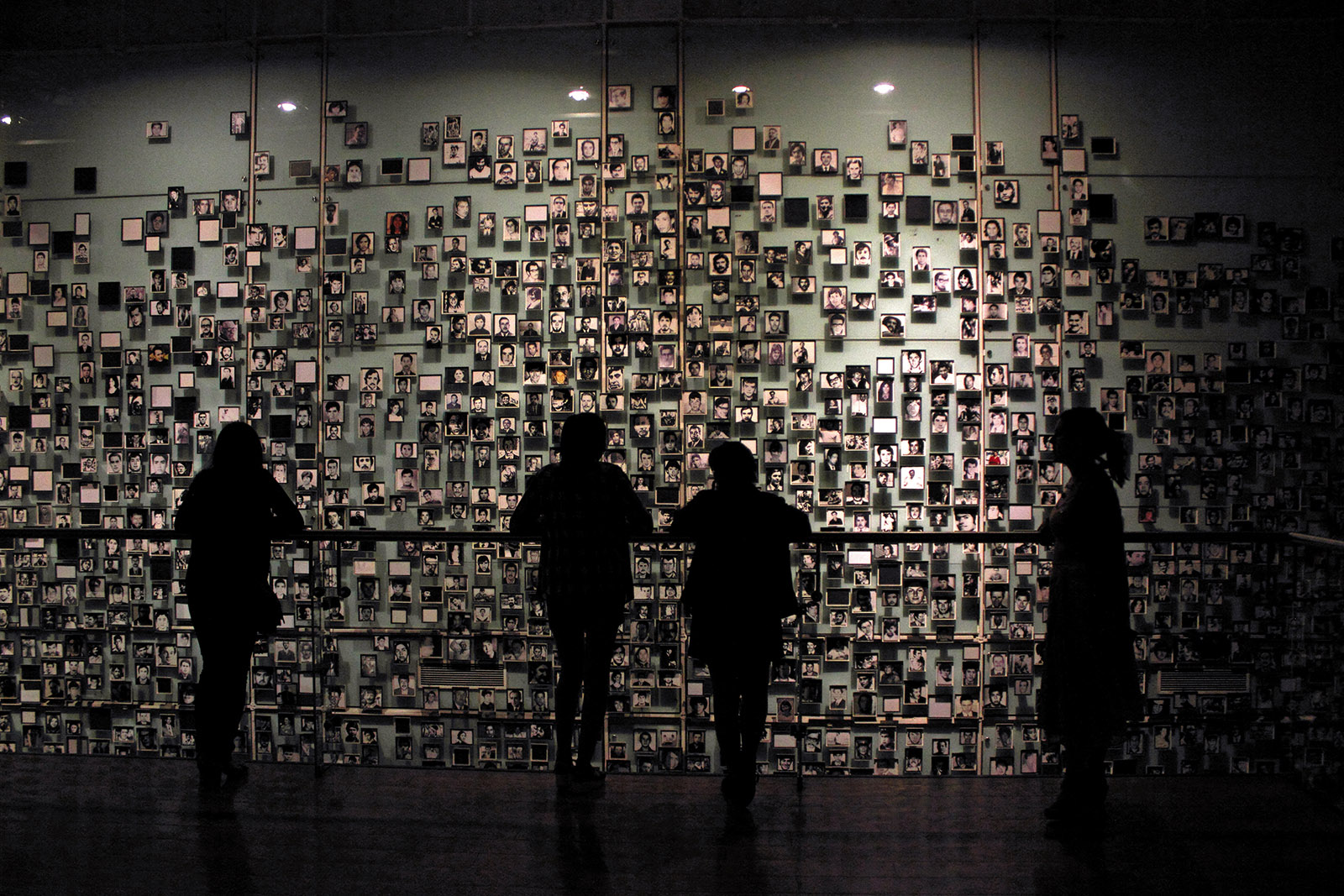

It took twenty years after democracy was restored, but finally, in January 2010, President Michelle Bachelet, herself a victim of the dictatorship (she and her mother had been detained and tortured after the death of her father, an air force general loyal to Allende), inaugurated the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos (Museum of Memory and Human Rights) in Santiago.4 The museum owes its collection of archival materials largely to the efforts of human rights organizations to record abuses by government officials during Pinochet’s rule. The ground floor of the museum offers a moving and detailed story of the coup and its ferocious aftermath, but the most arresting display awaits visitors on the second floor of the majestic building, where a balcony overlooks a wall of photos fifty feet tall. The 3,197 images depict the faces of Chileans executed extrajudicially by the military government, including 1,102 desaparecidos, whose abducted bodies remain, to this day, missing and unburied.

The sorrow evoked by this reminder of devastation is mitigated by a velatón, a shrine made of candles (velas), that burns perpetually along the inner rim of the balcony. It is a ritual in Latin America to erect modest altars—flowers, candles, mementos, written prayers—where someone has met a violent end, and where the living can ask the animitas (little souls) for help. This popular tradition enacts the message that a museum dedicated to memory is designed to convey: remembering the dead is a way of keeping them somehow alive, and not so alone.

In this case, the velatón (velar in Spanish is to keep a vigil) is also meant to remind visitors of the candles that multiplied on sidewalks across the country during the protests that shook the foundations of the regime, as well as the candles Chileans lit in front of detention centers where their loved ones had once been held. The balcony also features a small digital screen that allows a particular victim’s name to be typed in so that the person’s photo lights up on the wall, along with information about his or her fate.

Like many Chileans who journey to the museum, I carry with me a litany of my own dead. At every turn, the museum emphasizes that the sacrifice of the victims was not in vain. In room after room, videos, newspaper clippings, radio programs, documents, objects, crafts made by political prisoners, and personal testimonies tell us that the rebellion that cost so many lives was part of a widespread movement of resistance that would ultimately defeat Pinochet’s dictatorship. This intimation of hope—that there is a meaning to so much pain and loss—is no ordinary accomplishment.

Advertisement

A few days earlier I had visited Villa Grimaldi, the most infamous secret torture and extermination center in Chile, now a park dedicated to peace, and it was not solace that I found there, but rather an anguish that I barely knew how to deal with. While the museum provided a sense of safety and coherence, Villa Grimaldi—a place where so many friends howled and bled and pleaded as they were tormented and killed, a demonic place that is not easily exorcised—made me confront the tragedy in an entirely different way.

Nestled in the hills below the Andes, Villa Grimaldi, a nineteenth-century casona (mansion), hosted many artists, intellectuals, and liberal politicians during the Allende years. Its lavish grounds included orchards, Italian-style fountains, a pool, and mosaics. In 1974 the estate was taken over by the DINA, Pinochet’s secret police, and turned into a camp where thousands of prisoners were interrogated and brutalized over a four-year period. Villa Grimaldi’s outrages were minutely registered by human rights organizations in the aftermath of the coup, notably by the Catholic Church’s Vicariate of Solidarity. This extensive denunciation and documenting of abuses from the very start of the military government—a strategy of defiance that distinguishes Chile from dictatorships in Latin America and around the world where there was limited space for that sort of legal resistance—would help to refute the incessant lies of the regime.5

But the sort of archival and judicial work that registered the repression in Villa Grimaldi could not save its premises for posterity. Soon after closing the torture center in 1978, the secret police bulldozed the villa and all of the structures on the property that had served as torture chambers. When, many years later, real estate developers began to excavate the site in order to build condominiums, neighborhood associations and groups of survivors protested so vigorously that the democratic government expropriated the land. In 1997 it was opened as a park, with gardens and ponds and trees, where the public could learn about and reflect on the past.6

Villa Grimaldi is only fifteen blocks from the house in Santiago where my wife, Angélica, and I spend some months every year, but until this Chilean summer I had never gone there. I admired the efforts to rescue a site that so many powerful people in Chile wanted to obliterate, and knew that it had become a center where victims congregated, and where concerts, protests, theatrical performances, and seminars were held, but I could not overcome my stubborn reluctance to visit its grounds. I was convinced by the view of an old friend of mine, a major artist who had been tortured there (he prefers not to disclose his name): “They should have left it as a ruin, in all its ugliness, not try to beautify it. We should let spaces like those speak for themselves, let the silence speak, so people can absorb without mediation the full horror of what happened there. One way of erasing the past is by remembering it in the wrong way.”

Similar arguments have been made by Holocaust survivors. My friend was concerned that the villa’s beautification would have “erased the past” by dulling the pain of remembering it; but for me the loveliness and peace of Villa Grimaldi enhanced the desolation. The wondrous trees, commemorative rose gardens, and reflecting ponds made my distress more acute as I came upon the names, on plaques, memorials, and posters, of students I had taught, comrades with whom I had studied Hegel and Fromm, a cinematographer I had worked with on a television show, men and women who had marched by my side and Angélica’s on the streets of Santiago in defense of the revolution. But one name in particular kept appearing and tested the fortitude of my memory, which had suppressed so many disturbing losses.

Fernando Ortiz Letelier had befriended me in the early 1960s, when I was a nineteen-year-old student of literature at the University of Chile and he was a professor of history two decades my senior. During long walks through our leafy campus, he told me about his groundbreaking research into the early fight by Chilean workers for justice and democracy that created the conditions for a revolution through the ballot box rather than through the violence dogmatically proposed by most Marxists.7 Our relationship intensified when Fernando married María Luisa Azócar, a dear friend of our family.

He and I did not share the same views on everything (as a convinced Communist, he defended the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, while I was an ardent admirer of the Prague Spring), but we agreed on the radical reforms needed to end the misery and exploitation in Chile, and we became even closer during Salvador Allende’s three-year experiment in democratic socialism. Peasants became the owners of their land, workers managed their own factories, the resources of the country that had been plundered by foreign corporations were nationalized, with the profits going to health and education, children were given free milk at school, and millions of books were sold at negligible prices at newsstands.

Advertisement

The last time I had seen Fernando was on the morning of the 1973 coup, when he addressed a group of militants at our campus and proclaimed his faith in the ability of the Chilean people to overcome the repression that awaited us—and him. On December 15, 1976, he was kidnapped by agents of the intelligence services a mere three blocks from the university grounds where he and I had so often dreamed of a bright future. It would take many years to find out what had happened to him. A trickle of information placed Fernando at Villa Grimaldi, but after that all traces vanished. It was feared that he had been thrown from a helicopter into the Pacific Ocean, like Marta Ugarte, a militant whose body had washed up on a beach, strangled and terribly mutilated, in September 1976.

That had not been his fate. In March 2001 a judge announced that forensic experts had identified tiny fragments of his bones and teeth dug up from a cavern deep within the Cuesta Barriga, a massif near Santiago. The rest of his body had been blown up in an undisclosed location, part of a clandestine operation ordered by Pinochet to remove evidence of the murder of countless dissidents. Called Retiro de Televisores, it was mostly effective at disappearing the corpses of an estimated 150 victims of kidnapping and murder.8 Fernando Ortiz was one of the few whose scant remains were recovered and subsequently buried in a symbolic funeral, giving his tormented family a measure of relief.

Watching these events from the United States, where I had established my permanent home, I also felt that I could somehow put him to rest, stop obsessing about his agony. For some years I had been gradually protecting myself from the grief over past atrocities, but in the process I had, in effect, forgotten Fernando Ortiz. But now Villa Grimaldi stirred up images of my friend beset by curses and convulsions. That was not how I wanted to remember him.

I seemed to be the only one making the rounds of the gardens at Villa Grimaldi, the only one mourning not just the passing of this friend and so many others, but also the just society we had wished to build during the Allende years. As I sat down beneath the incongruous beauty of an ancient tree, I noticed a couple of workers finishing the masonry of a cabin that was a replica of the quarters where the secret police had once forged identity cards and license plates. From a neighboring condominium a boy, perhaps eight or nine, was also staring from his apartment window at the men at work in the placid gardens. Had anyone ever told him the story of this park? My own bereavement seemed to fade in his presence. It was for children like him that this place and other sites of memory had been rescued, so that future generations may understand that remembering the traumatic past is essential to avoid its repetition. Alas, it is not certain that this struggle for memory will be successful.

Francisco “Pancho” Estévez, the historian who, at sixty-three, has recently been appointed the director of the Museo de la Memoria, was once a star student of mine at the University of Chile. During the Allende years, he helped me run literary workshops in shantytowns and make cultural television programs. After the coup, when the army took over the university, he was expelled for, among other reasons, conspiring with me to subvert the established order.

The expulsion had not dampened his revolutionary ardor, as I discovered when, in July 1975, Angélica and I were asked by the Chilean Resistance to host him in Paris, where we were exiled at the time. Pancho was traveling covertly to a socialist country for six months of training and had seven days to create a Parisian identity so he could send proof back home to his family and fiancée that he was indeed spending half a year in the French capital. After that intense week we lost contact, though we were sure that the ruse had worked: there was no news that he had been arrested upon returning to Santiago. Later, I found out that he had eluded the DINA and had a prominent part in the youth movement against Pinochet. When Chile was again democractic, Estévez led a series of educational human rights initiatives, most notably a campaign to remove numerous monuments that the dictatorship had erected to celebrate its “achievements,” such as the “Eternal Flame of Liberty” that Pinochet had installed in front of the Presidential Palace.

When I visited the museum in late February, Sebastián Piñera was about to be inaugurated as president of Chile. It was the second time his right-wing alliance had beaten the center-left coalition that has ruled Chile since 1990. Piñera, a billionaire who made a fortune thanks to Pinochet’s laissez-faire policies, has democratic credentials. In a 1988 referendum, he voted against the general’s perpetuation in power. But he surrounds himself with advisers and ministers who were enthusiastic promoters of the dictatorship, and he owes his victory to the support of José Antonio Kast, a neofascistic, populist defender of Pinochet backed by a decisive 8 percent of the electorate.

Piñera’s victory has emboldened “denialism,” the tenacious crusade by powerful Pinochet fanatics to proclaim that the interpretation of the past by the Museo de la Memoria is skewed and biased. They claim that the state must be fair to both sides and fund a “Museo de la Democracia” that will provide context (in other words, justification) for the coup against Allende and absolve the military (and its civilian accomplices) of responsibility for atrocities committed in its attempt to save the fatherland from socialism. Despite such initiatives, Pancho doubts that there will be cuts to the museum’s budget. Both houses of Congress are controlled by center-left parties, fractured and disoriented though they may be. And thousands of human rights advocates have warned that attempts to undermine the museum would be met by street protests and an indefinite sit-in outside the building.

It can seem as if the lessons of Chile’s neofascist takeover are quickly being forgotten. Crime is perceived by many to be on the rise, creating nostalgia for drastic “law and order” policing. A flood of immigrants, primarily from Colombia, Peru, and Haiti, many of them black, has generated a xenophobic backlash peppered with appeals to defend the “purity” of a mythical Chilean “race.”9 Proponents of reinstating the death penalty have become more vocal: masked vigilantes (members of a rabid homophobic group) recently hung four mannequins from a bridge in Santiago to proclaim how the state should deal with pedophiles. And acts of vandalism by extremists on the margins of a peaceful indigenous rights movement have generated demands for new antiterrorism legislation, which many Chileans welcome even though it recalls the language and excesses of the dictatorship.

Estévez is undaunted by this possible shift in the national mood. He has always seen the battle for collective memory as a continuous struggle. To the Museo de la Memoria’s foundational maxim, Nunca Más (“Never Again”), he has added a new motto: Ahora, Más que Nunca—“Now, More than Ever.” “If we only look backwards,” he told me, “we will not have really fulfilled our mission. For that, we need to engage the current problems of Chile and the world, the dilemmas that motivate young people, above all.”

All temporary exhibits at the museum explore the past but can be connected to current crises. “Secrets of State: The Declassified History of the Dictatorship” both examines the US’s involvement in the overthrow of Allende and subsequent patronage of Pinochet and warns visitors about the perils of a surveillance state.10 Another exhibit highlights the resistance by trade unions to the dictatorship’s neoliberal policies, a mobilization that may resurface if the Piñera government tries to set back reforms in education, health care, and pension plans. A third shows how thousands of residents of low-cost apartment complexes built at the Villa San Luis during the Allende presidency were uprooted to make way for luxury real estate developments, an episode worth remembering as the gap between the very rich and the rest of the country widens.

I left the museum that day inspired by Pancho’s calm optimism. Even so, the vision of that child who had watched Villa Grimaldi from the oblivious safety of his home would not go away. Leaving aside the question of the efforts required to reach someone like him, is it fair to overwhelm him with a tragedy not of his making?

When I returned to Villa Grimaldi for a second time, in search of an answer, I noticed that a wall skirting the far side of the park was covered not with the names of the dead, but with mosaics. Along with the gates of Villa Grimaldi, it is the only element of the original premises that has not been demolished. Former detainees remembered that wall vividly. Stumbling and starving and blindfolded, beaten and humiliated, they had been hurled like garbage against that wall of mosaics where they had found, to their surprised relief, a cool refuge from the unbearable heat of the Chilean summer. Years later, many of them were able to confirm that they had indeed been imprisoned in Villa Grimaldi because their hands recognized the texture of that wall.

I placed my hand where their hands had touched those tiles, where Fernando’s fingers may have impressed themselves one desperate afternoon. Perhaps someday the boy from the neighboring condominium would also place his hands here, become one more link in the chain of communion and memory, claim the heritage we must never forget, ahora más que nunca.

This Issue

August 16, 2018

The ‘Witch Hunters’

The American Nightmare

The Queen of Rue

-

1

The reports of the Valech Commissions 1 and 2 can be consulted at bibliotecadigital.indh.cl/handle/123456789/185 and bibliotecadigital.indh.cl/handle/123456789/600. ↩

-

2

Among the many books by the Chilean psychologist Elizabeth Lira and the American historian Brian Loveman that illuminate the complex history of memory and reconciliation in Chile, two are indispensable to understanding the challenges facing the country after 1990: El Espejismo de la Reconciliación Política (LOM, 2002) and Políticas de Reparación: Chile 1990–2004 (LOM, 2005). ↩

-

3

See Patrimonio de la Memoria de los derechos humanos en Chile (sitios de memoria protegidos como monumentos nacionales, 1996–2016), Santiago de Chile, published by the Chilean government in 2017, and Alexander Wilde’s review of Narrow but Endlessly Deep: The Struggle for Memorialization in Chile since the Transition to Democracy by Peter Read and Marivic Wyndham (Australian National University Press, 2016), in The Public Historian, Vol. 40, No. 1 (February 2018). ↩

-

4

See ww3.museodelamemoria.cl/exposicion-permanente/ for a description, room by room, of the museum. ↩

-

5

See the three volumes of Chile: La Memoria Prohibida, edited by Eugenio Ahumada (Pehuén, 1989). See also Los Archivos del Cardenal: Casos Reales, edited by Andrea Insunza and Javier Ortega (Catalonia, 2011). ↩

-

6

Two of the most important works on the subject are Gabriel Salazar, Villa Grimaldi (LOM, 2013) and Parque por la Paz Villa Grimaldi, una deuda con nosotros mismos, written and designed by the survivors themselves, published in 2013 by the Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. See also Michael Lazzara’s description of his visit to Villa Grimaldi in Chile in Transition: The Poetics and Politics of Memory (University Press of Florida, 2006). ↩

-

7

See Fernando Ortiz Letelier, El Movimiento Obrero en Chile (1891–1919), his 1956 doctoral thesis, published posthumously in 1985 by Michay in Madrid, and reprinted by LOM in Santiago in 2005. ↩

-

8

The “television sets” were the bodies of those executed, to be “withdrawn” (retirados) from where they had been hidden. ↩

-

9

See my “A Lesson on Immigration from Pablo Neruda,” The New York Times, February 21, 2018. ↩

-

10

The exhibition, which closed on March 18, was curated by Peter Kornbluh, author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability (New Press, 2003), the definitive book on American meddling in Chile’s internal affairs. ↩