Donald Keene’s magnum opus, fifteen years in the writing, was A History of Japanese Literature in four immense volumes, an account of the entire national literature from the eighth-century creation chronicles to Mishima Yukio in the 1960s. Anyone who has spent his professional life sweating and cursing over Japanese texts is awestruck by the quantity of Japanese writing Keene managed to absorb—he was a Herculean reader. Detractors complain that he was more descriptive than critical, but that is a cavil designed to reduce him to life size.

John Treat, in his introduction to The Rise and Fall of Modern Japanese Literature, derogates Keene for precisely what others say his work lacks: his critical judgment. In Keene’s unequivocal verdicts as a critic—“lightweight,” “immoralist,” “never fully understood”—Treat finds an intention to leave his readers with something permanent:

His literary history was one, he believed, that would not require amendment. It would be the truth of modern Japanese literature rather than a cultured appreciation of it…. This is the naïve dream of some historians: to fix and make a sure record of the past.

Treat lists additional complaints, but he concludes with what feels like an intended compliment when he reckons it is Keene’s history to which his book will be compared.

Treat’s purpose is to “reexamine certain key conjunctions in the history of Japan’s modern literature where we can excavate just how literary texts came to embody emerging, dominant or resistant strategies of power in society.” He has read Jürgen Habermas and Fredric Jameson, who together do their share of the conceptual heavy lifting in his book, and so it comes as no surprise that he should focus on capitalism as the principal socioeconomic force reflected in and acting formatively upon the works of fiction he considers.

Moving from the late nineteenth century to the present by leaps and bounds, Treat arrives at a conclusion that links late-stage capitalism to the end of modernity and, ipso facto, to the demise of modern Japanese literature. If he has provided a cogent description of “modernity” in this study, I have not found it. He does, however, characterize certain social and psychological transformations as inimical to the modern: the atomization of Japanese society in the 1980s, for example, for which he holds the proliferation of manga significantly responsible. In support of his claim, he quotes a literary critic who asserts that a book can be shared with others at a public reading but that “manga is never manga except when you direct your gaze at someone who is no other but you.” With that shift from “by all of us” to “just for you,” Treat writes, “Japan started to edge past its short-lived, modern forms of literary colloquy and now approaches the precipice of what comes next.”

Treat argues that after Japan’s economic crash in 1991 and the horror of Aum Shinrikyo’s sarin attack in 1995 fantasy became harder to distinguish from reality in Japanese fiction. He begins his chapter on Murakami Haruki with the real-life story of Miyazaki Tsutomu, a serial killer of young girls who was arrested in August 1989 and subsequently diagnosed with multiple personality disorder (MPD). In Treat’s interpretation, Murakami’s inert, baffled characters are similarly afflicted with MPD, as if the border between reality and fantasy has disappeared for an entire generation. His explanation accords with his basic premise: “I suggest that MPD…and other dissociative phenomena, whether real or fantastic, are linked to how labor and production are changing in a postindustrial Japanese economy.” This unsubstantiated proposition generates the book’s most opulent metaphor: “The current structure of feeling as multiple becomes perceptible, in fiction, via the inchoate thoughts that literary characters somehow sense are not always their own—the ventriloquism of capital.”

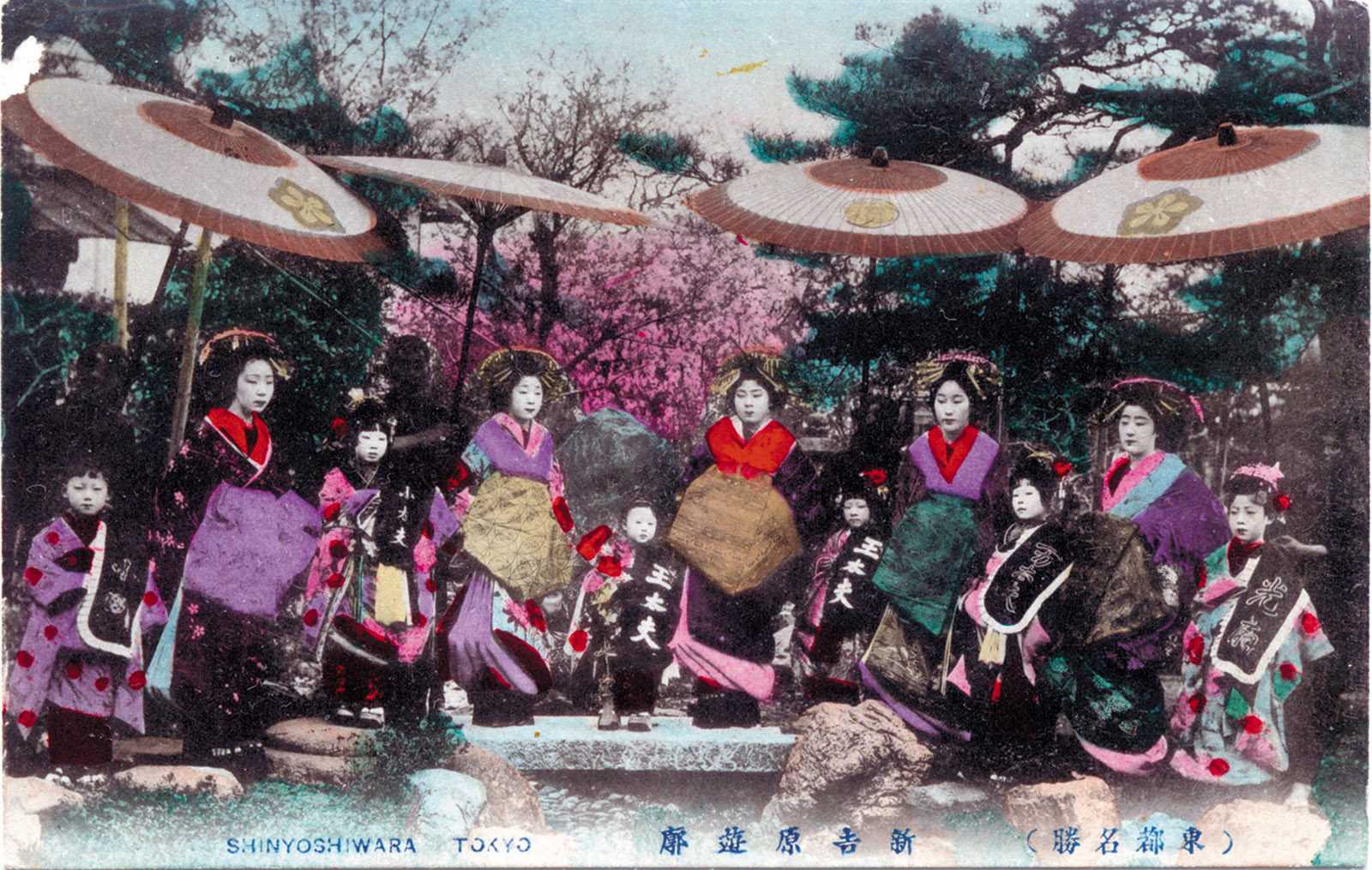

Treat has chosen literary landmarks that offer him fertile ground for an “excavation”—his choice of the word is telling—of the social and economic forces at work on them. One of these is Higuchi Ichiyō’s Growing Up (Takekurabe). Serialized in 1895, one year before Ichiyō’s death of consumption at the age of twenty-four, the novella observes a group of adolescents on the brink of adulthood living in the shadow of the walls that surrounded the Yoshiwara, Tokyo’s notorious brothel district. Nobu, sixteen, is destined to forsake the material world and become a Buddhist monk like his father; Midori, fourteen, has been indentured to a brothel by her parents and will soon become a prostitute like her elder sister. These childhood friends awaken to their romantic feelings for each other, but they clearly have no future together. It is the impossibility of unsullied love—in implied distinction to the tawdry game inside the walls of the Yoshiwara—that imbues the story with the wistful melancholy that one associates with Ichiyō.

Advertisement

Treat asks whether Growing Up is, “if not about the industrial labor force of early Japanese capitalism, nonetheless made sensible by the social forces at work in creating a modern Japanese working class?” On the way to his predictable answer, he provides a lengthy description of the burgeoning textile industry in which he quotes Patricia Tsurumi on “the brothel as an alternative to the loom,” implying that Midori, as a sex worker, is similar to Japan’s exploited female factory workers. He also observes, in passing, that both English translators of the novella have omitted a word that appears twice in Ichiyō’s original, kensaba, an inspection station for venereal disease to which prostitutes were required by law to report once a week (gonorrhea was rampant). He is correct. Edward Seidensticker’s early translation, abridged in any event, expunges the word both times. Robert Danly deletes it once and translates it once as “the hospital,” an obfuscation that seems likely to have been intentional. (There is a tradition of the translator as prude in modern times that begins with Arthur Waley.)

Treat might have said more about inspection stations that would have reinforced his proposal that Growing Up was informed by the dynamics of capitalism. Late in the story, the pawnbroker’s son, Shōta, thinking about Midori, with whom he is also infatuated, hums a ditty to himself: “Growing up/She plays among the butterflies and flowers/But she turns sixteen/and all she knows is work and sorrow.” This was a popular song of the day, and so contemporary readers would have noticed that Ichiyō had conspicuously omitted the line “visiting the inspection station,” thereby, presumably, directing readers’ attention in her unobtrusive way to the sordid reality. Some scholars in Japan have even proposed that an unmentioned first visit to the kensaba might explain a plunge in spirits that darkens Midori’s mood near the end of the story: “If only she could hide in a darkened room and pass the time alone…it was hateful, just hateful, how she hated becoming an adult!”

Treat concludes that Growing Up is “a virtual log of Meiji-period economic reorganization along the lines of classic economic liberalism,” an extrapolation that seems schematic but plausible. At the very least, Higuchi Ichiyō doubtless knew that three thousand women were prisoners of the sex trade inside the Yoshiwara, and might well have intended a condemnation of a social system that tolerated the sale by parents of daughters into prostitution.

But surely Growing Up is more than a tractate on the evils of class and economic determinism. In his zeal to uncover capitalism at work on art, Treat overlooks the art itself: Ichiyō’s lambent prose, her gentle irony, the vividness of her treatment of innocence threatened. Readers unfamiliar with Growing Up will come away with no idea of its distinctive tone or flavor, qualities in any work of literature that are as important as its historical significance.

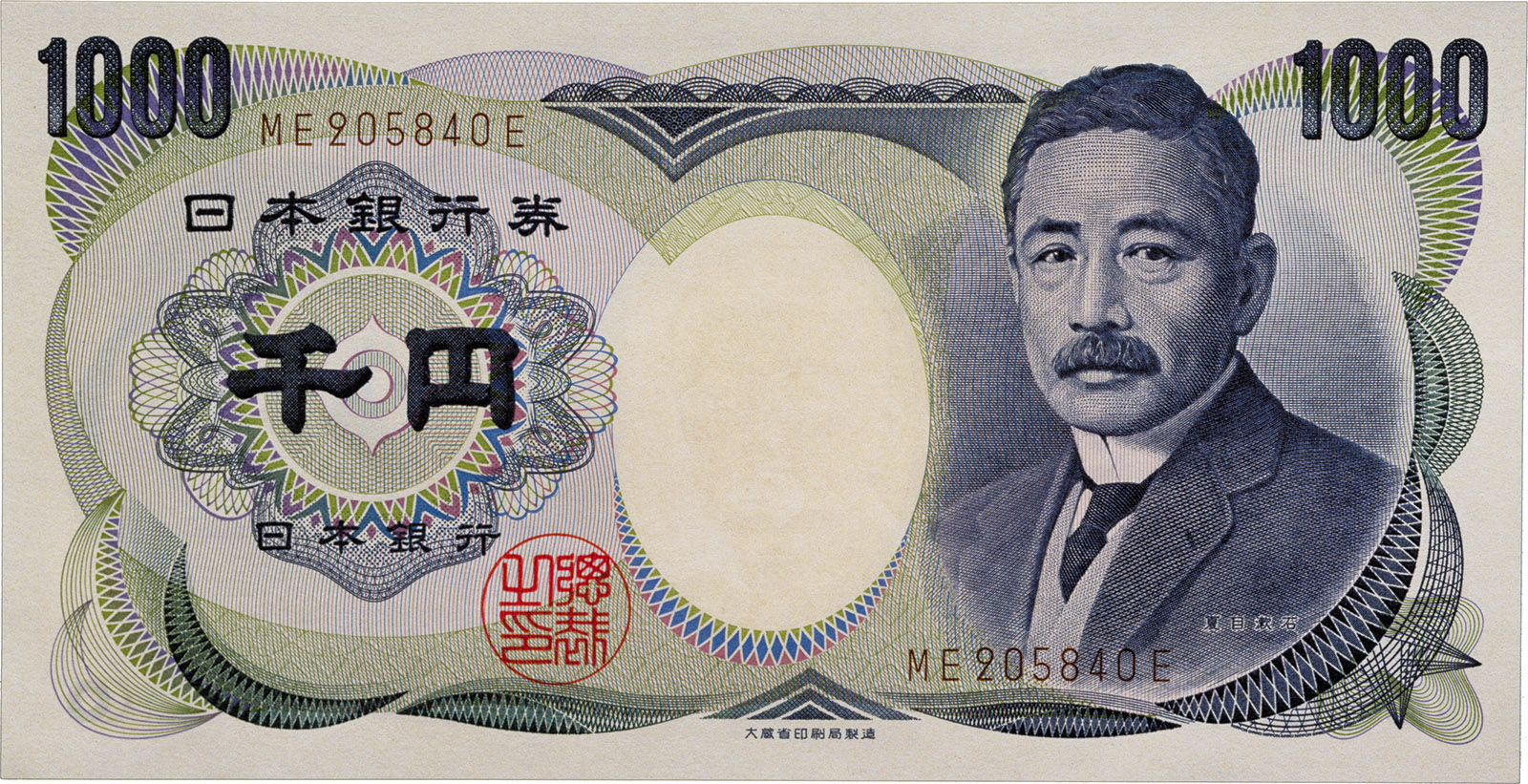

Treat’s appraisal of Natsume Sōseki’s I Am a Cat (Wagahai wa neko de aru, 1905) is unsatisfying in a similar way. The “context” in which he views the novel is “the shifting stakes of orality and literacy in a developing modern nation-state.” He reads the polyphony of I Am a Cat not, as the scholar James Fujii would have it, as “resistance to what he calls the monologic subject of a state-sponsored linguistic project,” but rather as reflecting participation in the “ongoing negotiation of competing hegemonies.” At the center of his argument is rakugo (“fallen words”), a form of storytelling with roots in the urban merchant culture of the mid-seventeenth century. Treat suggests that the importance of I Am a Cat to Japanese literary history is its “orality within textuality”: by incorporating the sensibility and the narrative strategies of rakugo in his novel, Sōseki at once “preserve[d] traces of an orality not found in textual culture” and participated—colluded—in the transformation of the oral into the literary hegemony controlled by the state.(Sōseki, by the way, is commonly known by his first name, as is Higuchi Ichiyō.)

Treat’s analysis is incisive in the abstract. But again he gives the uninitiated reader no taste of the original text. I Am a Cat is a mordantly comic evocation of Sōseki’s pessimism about his own humanity and indeed about humankind in general. The central figure, a self-lacerating parody of the author, is an English professor named Kushami (Sneeze) with all the pretensions to Western sophistication that characterize the Meiji-period intellectual. Sneeze receives constant visits to his study from his cronies: an aesthetician whose name translates as “Doctor Bewildered,” a fatuous pedant at work on a “history of hanging,” a “new playwright” working on “the haiku theater,” and several others. The feline narrator, an alley cat who has taken up residence in Sneeze’s house, comments in mounting dismay on the conversations it overhears, and concludes that humans are “selfish and immoral.”

Advertisement

I Am a Cat may well represent a “key conjunction” of hegemonies. What makes it a best seller to this day, however, is its wit and a dazzling, Mozartian display of variation and embellishment. The badinage at the heart of the book is rendered with an ebullience that evokes the pleasure Sōseki takes in his ability to bring it off and extend it inexhaustibly, a joie d’écrire that is in itself irresistible.

Apart from the canonical Growing Up and I Am a Cat, Treat’s choices of texts are eccentric. Included are an 1870s series of illustrated stories about a femme fatale (Torioi O-Matsu Gōkan, 1878); Fukazawa Shichirō’s regicidal fantasy “The Tale of a Dream of Courtly Elegance” (Furyū Mutan, 1960); a cohort of Korean writers producing colonial literature in Japanese; Nagai Gō’s manga series Shameless Academy (Harenchi Gakuen, 1968); and The Rise and Fall of Japanese Literature (Nihon Bungaku Seisui-shi, 1997–2000), a parodic time-bender by a writer largely unknown to Anglophone readers, Takahashi Gen’ichirō.

Treat predicts that he will “soon be lectured on all [his] omissions,” and I am happy to take that bait. Most egregiously, aside from a remark that he is “a synecdoche” for postwar Japanese fiction, the 1994 Nobel Laureate, Ōe Kenzaburō, is scarcely mentioned. Omitting Ōe from any literary history of the twentieth century, no matter what its vantage, is difficult to justify. It is an especially striking omission in light of Treat’s central argument: no other writer has embodied and shaped as unmistakably as Ōe the sociopolitical environment of the time in which he lives.

Failing to include Ōe in Chapter Seven (“Beheaded Emperors and Absent Figures”) leaves a particularly gaping hole. The centerpiece of the chapter is Fukazawa Shichirō’s story “The Tale of a Dream of Courtly Elegance,” which appeared in a literary magazine in November 1960. In this surreal parody, the imperial family is sentenced to death, and the decapitated head of the crown prince rolls across the floor, “bumpety-bump-bump.” (The phrase in Japanese, sutten-korokoro, is an untranslatable onomatopoeic adverb commonly used to describe a pratfall on a slippery surface or tumbling “head over heels.”) The irreverence of the story—particularly Fukazawa’s application of such an adverbial modifier to the severed head of a royal—ignited a furor that led to murder. On the night of February 1, 1961, a right-wing fanatic forced his way into the home of the publisher intending homicide and, learning that he was out, wounded his wife and stabbed the maid to death. Fukazawa went into hiding for decades, pursued by death threats and supporting himself as a ticket scalper, pimp, and traveling salesman.

Treat writes that “The Tale of a Dream of Courtly Elegance” “change[d] the course of modern Japanese literature,” a far-fetched claim he fails to support. He does hypothesize creatively a connection between the murder and the spread of television into one million households by 1959. In that year Crown Prince Akihito (now the emperor soon to abdicate) married Shōda Michiko, a commoner he had met on a tennis court. The unceasing TV coverage brought the imperial family down from on high, where they had remained for centuries beyond the observation of their subjects, into Japan’s middle-class living rooms. The effect of this domestication, Treat reasons, was a debasement of the family’s image that culminated in the royal head going bumpety-bump-bump.

He mentions only in passing another event that had a more significant impact on Japan’s literary history—possibly, to borrow his own formulation, because it was recorded live on TV. On October 12, 1960, the chairman of the Japan Socialist Party, Asanuma Inejirō, was giving a campaign speech when a young man leaped to the stage and plunged a short sword into his corpulent body. Asanuma dropped to the ground, dead on the spot. NHK, Japan’s national public television company, was taping the speech for later broadcast, and the assassination was shown repeatedly to millions of Japanese. The assassin, a seventeen-year-old named Yamaguchi Otoya, managed to hang himself in jail, eliciting praise for his adherence to the warrior code from Mishima Yukio.

In January 1961, three months after Asanuma’s death, Mishima published a forty-page story, “Patriotism” (Yūkoku), a florid celebration of ecstatic sex and subsequent harakiri in the emperor’s name that was modeled on a 1936 rightist insurrection but almost certainly inspired by the assassination. That same month, in an arresting coincidence, another magazine published a story by the twenty-five-year-old Ōe Kenzaburō called “Seventeen,” a parody of an ultranationalist who turns killer that was as sardonic as “Patriotism” was devout. The hero of “Seventeen”—the same age as Asanuma’s assassin—is a chronic masturbator who finds a haven from the impotence he feels in the face of others in selfless fealty to the emperor. “Ah, Your Majesty,” he exults, masturbating to the imperial image, “Even if I die, I will never perish. Because I am nothing more than one young leaf on one branch of a giant eternal tree called His Majesty the Emperor. Ah, you are my god, my sun, my eternity. In you, oh, by you, ah, I have truly begun to live.”

Fukazawa’s “Tale” was farcical, an outlandish story related facetiously. Ōe’s exercise in grotesque realism was a serious indictment. He too received repeated death threats; he spent a year confined to his house, where a police car kept watch outside at night. Today, as Treat points out, Fukazawa’s “funny little story” is available in a Kindle edition but largely forgotten. Part two of “Seventeen,” “The Death of a Political Youth” (Seiji Shōnen Shi-su), has not appeared in print since it was originally published and its looming absence has kept it alive in memory within Japan’s community of writers.

In his chapter on Yoshimoto Banana, Treat aptly calls her 1988 debut novel, Kitchen (Kitchin), “Japan’s first intellectual global commodity,” an observation consonant with his insistence that literature embodies the mode of capitalism ascendant at the moment. The heroine of Yoshimoto’s deceptively simple best seller, Mikage, finds solace in the “cozy warmth” of well-appointed kitchens, sleeps next to the refrigerator on anxious nights, and hopes “to breathe her last in a kitchen.” Devastated by the death of her grandmother, she moves in with Yūichi, an impassive young man who lives with his mother, Eriko, a transgender woman who was formerly his father. (Treat argues that the deformed Oedipal structure that Yoshimoto engineers is a simulacrum of the breakdown in capitalist structure we are now experiencing.)

The unlikely new family is briefly happy together—Mikage describes her feelings about Yūichi’s kitchen as “love at first sight”—until Eriko is murdered by a madman obsessed with her. Mikage and Yūichi are left alone surrounded by death, uncertain if they can share a life as both brother and sister and man and woman “in the primordial sense.” Mikage conveys an indifference about the future: “In the biting air I told myself, there will be so much pleasure, so much suffering. With or without Yūichi.”

Treat neglects to mention a quirky book that preceded Kitchen and might have given him another persuasive example of the relationship of literature to consumerism. In 1980, a college senior at Hitotsubashi University named Tanaka Yasuo, the future left-wing governor of Nagano Prefecture, wrote a novel that sold one million copies within a year of publication. The Japanese title, Nan to Naku Kurisutaru, is a challenge to translate. Nan to naku means “somehow,” “sort of,” “in a vague way.” Kurisutaru, a phonetic rendering of the English “crystal,” was a term in vogue connoting “wealthy,” “beautiful,” “cool,” and, the aggregate of those qualities, “happiness.” The heroine, a twenty-year-old college student who is also a fashion model, exemplifies living a “vaguely crystal” life:

Junichi and I are living together without any worries. I buy and wear and eat things that somehow feel nice. I listen to music that sort of makes me feel good. I go to places and do things that are fun in a vague way. When I’m in my thirties, I’d like to be the sort of woman who looks good in a Chanel suit.

Vaguely Crystal is a less impressive achievement than Kitchen. What distinguished it was 440 footnotes that transformed it into a Baedeker of Tokyo’s fashionable restaurants, discos, and boutiques, and a glossary of European luxury items, hot bands, and hit albums. The annotator has an encyclopedic command of all the styles and manners that are the obsessive focus of his readers’ lives and conveys perfect confidence in his judgments:

Cointreau: The ne plus ultra of after dinner liqueurs.

Virginia Slims: A British cigarette. Somewhat feminine.

Fendi: Italian brand established in 1918. Famous in the 30s for fox muffs. Better known in Japan for handbags than furs.

Vespa: An Italian scooter that has become a little too familiar.

Vaguely Crystal is a paean to the consumerism of the 1970s and 1980s. At the same time, Tanaka’s epicurian commentary evokes the emptiness that underlies the single-minded pursuit of style and anticipates the accidie that flattens Yoshimoto’s book.

Not until his last chapter, “Takahashi Gen’ichirō’s Disappearing Future,” does Treat tell us explicitly what he means by the “fall” of modern Japanese literature. He relies on Takahashi, a novelist who came to prominence in the 1980s, to explain: “The twentieth century was so traumatizing that the ‘nation-state,’ nationalism and modern civil society are beyond repair. And since that is so, a modern literature with deep, inseparable ties to those things is so wounded that it cannot recover.”

Takahashi is crucial to Treat’s conclusion because he parodies literary history itself, and parody, in Treat’s notional scheme of things, signals the end of one thing—“a distinct and describable episode” called modernity—and the beginning of something unnamed. In Takahashi’s voluminous novel The Rise and Fall of Japanese Literature (Nihon Bungaku Seisui-shi, 2001), a title that Treat adapts for his book, the author shares a hospital room with Natsume Sōseki, who discusses wind surfing, used panties, and the Doors with a poet friend; Higuchi Ichiyō, fourteen years old, has a torrid affair with the poet and novelist Mori Ōgai; and her mother is employed as a bar hostess at the postwar “Ginza nightclub, Copacabana” (it was actually in Tokyo’s Akasaka Mitsuke district). Takahashi’s refusal to respect the historical process, interpolating the present into the past, signals to Treat that the modern is over.

As a vision of the unnamed something that will replace it, Treat introduces a 1,500-page science fiction novel called Yapoo the Cattle People (Kachikujin Yapū, 1956–1991) by the pseudonymous author Numa Shōzō. Two thousand years after a nuclear holocaust has dismantled all social structures on the planet, a matriarchal, white-supremacist, extraterrestrial regime enslaves the Japanese survivors and bioengineers them as human livestock—cattle-people called “Yapoo”—to serve as living toilets, sex machines, doormats, and so on. Early episodes were serialized in an underground sadomasochist fetish magazine (the French translation won the Prix Sade in 2006); when the final revisions were completed in 1991, fans threw a bondage/discipline party on the Tokyo docks. Treat reports unironically that one critic has called Yapoo the Cattle People “the best Japanese work of the second half of the twentieth century,” while another hails it as “the greatest work of Japanese literature ever.” The details he gleefully shares are not for the squeamish:

One chapter (“No Lavatory World”) is given over to explaining how bodily eliminations have been reworked into the food chain, with whites at the top, black slaves (who are allowed to dine on white people’s dirty underwear) in the middle, and the formerly Japanese Yapoo at the literal bottom…managing human excrement.

Yapoo and other examples, including a novel whose main characters have no recognizable anatomical gender, embolden Treat to conjure his own version of what the future holds. In his chapter on Murakami, he characterizes the serial killer Miyazaki Tsutomu as “contemporary Japan’s most iconic young man,” suggesting that he views madness as definitive of the current moment. Since he thinks that Japan is already living in a future that will make its way around the globe, “the local eruption of a bigger history now unfolding,” it stands to reason that his prediction should represent a threat not merely to Japanese society but to all of us. As modernity dwindles and disappears, “new things,” Treat writes,

making the future’s history for us, [will] appear on the horizon as old ones disappear…. They will be things not modern anymore, probably not Japanese, possibly not human, and hardly literature; and no future perfect work of fiction today, however prescient, can foretell what guise those things will assume when they come to stalk us.

Let us hope that he is wrong.

This Issue

August 16, 2018

The ‘Witch Hunters’

The American Nightmare

The Queen of Rue