The late-eighteenth-century cult of sensibility unleashed a torrent of weeping all over Europe. Chatterton handkerchiefs, printed in red or blue, flooded the market, depicting the distressed teenage poet in his garret; the suicide in 1770 of this literary prodigy and forger was later encoded into Romantic myth by Wordsworth, Keats, and Shelley. Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, published four years after Thomas Chatterton’s death and a smash hit, pushed crying to its erotic limit. Reading Klopstock together, Werther and his beloved but off-limits Charlotte touch (barely) and weep. “By releasing his tears without constraint,” Roland Barthes wrote, Werther “follows the order of the amorous body, which is in liquid expansion, a bathed body: to weep together, to flow together: delicious tears finish off the reading.” Werther’s English translator in 1786 made the connection between the real and the fictional suicide: “Nature had infused too strong a proportion of passion in [Werther’s] composition; his feelings, like those of our Chatterton, were too fine to support the load of accumulated distress; and like him his diapason closed in death.”

Sensibility flowed into Romanticism, and Romantic poetry inherited a complex obsession with tears. German piano-accompanied song, the lied, grounded in lyric poetry, is awash with them. But the simple tears of sensibility, like those of “Wonne der Wehmut” (Delight in Melancholy), Goethe’s poem published the year after Werther and set by Schubert in 1815—Trocknet nicht, Tränen der ewigen Liebe (“do not dry, tears of everlasting love”)—give way to the twisted tears of the Romantics: self-conscious, ironic, deadly. In Schubert’s faux-naïf bucolic song cycle to poems of Wilhelm Müller, Die schöne Müllerin (The Beautiful Maid of the Mill, 1823), we learn that crying cannot bring withered love back to life; the miller boy, disappointed in love, flings himself into the mill brook that had earlier absorbed his tears. His diapason ends in death. The crying in Schubert’s monumental twenty-four-song Winterreise (1827–1828), to words by the same poet, is more complicated. Tears won’t come; the heart is frozen. Death is not available as a release. By the time of Schubert’s last song cycle, Schwanengesang, which includes six laconic poems by Heinrich Heine, tears are cursed. The poet drinks them from his lover’s hands. Since then his body has withered; she has poisoned him with her tears.

One of the most striking scenes conjured up in Laura Tunbridge’s new book, Singing in the Age of Anxiety, a study of lieder singing in New York and London between the wars, is a coda, Lotte Lehmann’s tearful farewell recital in New York, nearly six years after the end of World War II, in February 1951. Born in 1888, Lehmann had been one of the great singers of the age. In the field of opera she was particularly associated with the works of Richard Strauss, who declared, in words that could have come straight out of a Schubert song, that “she sang, and the stars were moved.” Strauss was the last of the great lieder composers, and it was as a lieder singer that Lehmann ended her career. The speech she gave before her performance is a rhetorical bridge to an earlier age, echoing one of the most famous of lieder, Mendelssohn’s “Auf Flügeln des Gesanges” (On Wings of Song—another Heine text). “You were the wings on which I soared,” she told her pianist and her audience, “a flight into beauty and another world.” As was widely reported at the time, Lehmann broke down during her final encore. Here is Life magazine’s account:

She had sung these words of Schubert’s immortal song “To Music” (“An die Musik”) hundreds of times before, but this time was different. As the statuesque soprano came to the final lines her eyes began to fill with tears. She broke down with a sob and covered her face with her hands. The piano finished alone.

Tunbridge is aware of the “element of showmanship” involved in the soprano’s farewell: the involvement of her PR agent Constance Hope; the Life photo-story, complete with its picture of Lehmann “head bowed, face behind her fingers, as the pianist carried on.” But she also finds listening to Lehmann’s breakdown (a recording was made and can be found on YouTube) “deeply moving…mak[ing] one contemplate how to write about expressive surplus in performance, as well as aging and failing voices.”

Listening myself to Lehmann I hear this—though some of the supposed vocal failings of age can equally be heard as stylistic choices (portamento, short breaths, the persistent wobble)—but I am also struck by a Romantic continuity that Strauss’s tribute to Lehmann and Lehmann’s own tribute to her pianist and audience have already suggested. There is no sense from the recording that Lehmann is overwhelmed and cannot continue, no sense of something being stifled or of a rising emotion finally taking the singer by surprise (and it is remarkable that so much of the lied is about tears but that tears make singing utterly impossible). Instead she stops almost deliberately. Du holde Kunst (“you holy art”), she sings, enunciating that final t of Kunst, leaving the words ich danke dir (“I thank you”) that complete the poem to echo only in the mind as the pianist continues playing. And he does not in fact finish the song; the piano postlude is left unplayed, which reinforces a sense that this is a performance as much about the singer as the song.

Advertisement

There is something deeply Romantic about Lehmann’s lachrymosity, but also about her artful caesura. It reminds me of nothing so much as a song by Schumann, “Des Sennen Abschied” (“The Herdsman’s Farewell” from his Lieder Album for the Young), in which, midway through repeating the words im lieblichen Mai (“in lovely May”) Schumann has the singer break off. The word Mai is left unsaid, unsung, and the effect is as if the herdsman’s rising rapture has overwhelmed him.

Lehmann’s performance of “An die Musik” crystallizes one of the central paradoxes of lieder singing: a lyrical form with an emphasis on individual subjectivity is at the same time necessarily performative and, in the best sense, mannered. The effect is very often of intimacy and of natural expression, of authentic access to the heart. But the means are calculated by composer and performer, not a mere spontaneous overflow of emotion. The artful conspires with the artless.

The lied is a niche within a niche within a niche. At the same time it is one of the glories of European classical music, one of the deepest expressions of its methods and preoccupations, and was of enormous cultural significance in its heyday, which ran, roughly speaking, from 1814 to 1914. It had its place in the sun, and we are still living, as musicians, as lieder singers, and lieder listeners, in the afterglow of that glory. Franz Schubert recreated song as a crucial and serious genre, setting lyric poetry with an intensity and harmonic daring that dazzled his listeners; Robert Schumann and his protégé Johannes Brahms poured endless imaginative resources into the small confines of the lied; Hugo Wolf put it at the center of his short, productive life; Gustav Mahler moved seamlessly between song, symphony, and song-symphony; Arnold Schoenberg used the song form for his most radical experiments in harmonic disruption; and Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs (1948) were the final elegiac expression of an exhausted tradition. To be a serious composer in the Austro-German tradition you had to grapple with the lied; and in the case of Wolf, achievement in the field of lieder alone raised him to the pantheon.

All the while, song has self-consciously celebrated the smallness of its canvas and of its focus, often with a teasing directness. Auch kleine Dinge können uns entzücken (“small things can also delight us”) is how Wolf’s Italienisches Liederbuch opens; and Heine’s Aus meinen großen Schmerzen mach ich die kleinen Lieder (“from my great sorrows I make small songs,” set as one of Wolf’s unpublished juvenilia) could stand as a motto for the whole genre. Big, dramatic things can happen in lieder, great stories can be told; but a premium is placed on subjectivity, on both minuteness of attention and ratcheting up of intensity, which the magical combination of voice and piano can ideally supply. The means are at one and the same time intimidatingly austere and thrillingly infinite.

The subtitle of Tunbridge’s study—“Lieder Performances in New York and London Between the World Wars”—is teasingly narrow. If the study of lieder is a specialism—though one of enormous cultural interest—then a study of performances of lieder in the period between 1918 and 1945 in just two cities, even if those two cities are cosmopolitanism incarnate, is a super-specialism, and one that might seem to be of little interest to the general reader, even the general reader with an interest in cultural history.

Tunbridge herself describes her work as decentered. It doesn’t concentrate on what are usually thought of as the main musical issues of the twentieth century: the developments of big institutions, modernism, and popular music. Its interest and achievement are to show how a quintessentially Austro-German art form, grounded in the German language and deeply implicated in both German nationalism and German Romanticism, was transmitted into the late twentieth century and beyond, to become in the LP age the hallmark of cosmopolitan and civilized music-making.

Advertisement

The exclusive attention given to New York and London is crucial to Tunbridge’s story. Singers who wanted to make an international career made a beeline for these fabled centers of money and power. Lieder societies and recording projects (like Walter Legge’s Hugo Wolf Society in London) were hives of activity. “International hubs for the performance of classical music” then and now, New York and London also had “complicated relationships with German culture,” she writes. In the case of New York, this was due to a large and influential German immigrant population; and in London, a broad cultural connection—across a spectrum that stretched from intellectual affinity (think George Eliot) and dynastic entanglement (all those Hanoverians and Saxe-Coburgs)—veered between affectionate embrace and fear of invasion, literal and metaphorical. In both places, the German language was an issue, and Tunbridge’s tracing of the ups and downs of lieder singing in translation is subtle and extensive. The nationalism and chauvinism of World War I made singing in German a taboo in the Allied nations; by the time of World War II the sense of a broader crusade for cultural values made lieder recitals part of the defense of a “civilization in danger of being destroyed by fascism.”

Lieder singing today feels itself constantly under threat, much as classical music more generally does. Nevertheless the tradition continues and renews itself. Lieder recitals are to be found on programs from San Francisco to Seoul; students at conservatories are deeply involved in learning and performing German song; new lieder singers are presented in recorded form; and there has never been so much sophisticated and detailed study of both the composition and performance of lieder in the academy. Tunbridge shows us that these, like so many late-twentieth-century traditions, are invented ones: not a direct inheritance from the nineteenth-century crucible of the lied, but one mediated through the political struggles and technological developments of the interwar years.

Audio technology in the 1920s and 1930s advanced on a broad front: the spread of the gramophone as a domestic appliance to rival and replace the piano; electronic recording, which lent a new realism to recorded sound; the ubiquity of radio, which could transmit a wealth of music into every home; and the advent of talking pictures, which, with movies like Blossom Time or Unfinished Symphony (both released in 1934), brought lieder to the masses in what was for some a disturbingly sentimental vein. Fears abounded. The doyen of English music critics, Ernest Newman, dreamed a dream—a nightmare—in which singing machines replaced human beings. Perfection was not immediately achieved, but “after a hundred years or so, the secret of producing perfect consonants was discovered, and it became possible to produce faultless Lieder singing.” Newman’s newspaper rival Neville Cardus wrote the following of the baritone Gerhard Hüsch’s recording of Schubert’s great Winterreise, only the second complete version at the time of its release in 1933:

A reproduction as happy as this makes one wonder whether the day will not soon come when it will be a superfluous labour for us to attend a concert hall. Why leave the comfort of one’s house and risk the distractions of a concert-room if the gramophone is able to catch the essence of an interpretation, especially an interpretation of anything so intimate as Lieder.

In the end, the interaction between new modes of production and the performance of lieder was complex and subtle. As Walter Benjamin put it in his celebrated essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” Live performance is necessarily at the heart of classical music-making of all sorts; but technology has had a profound impact on responses to it and the expectations we have of it. As far as lieder were concerned, the gramophone in the drawing room offered a return to the Innigkeit, the almost metaphysical intimacy that had attended the birth of the genre and had been submerged sometimes in the excesses of late Romanticism. In an introduction to a radio broadcast by Elisabeth Schumann in August 1938, the announcer spoke of “an art of glow, not glitter; a personal outburst from a poetic wanderer to a fireside listener, untheatrical and only indirectly dramatic.”

This certainly captures crucial aspects of the lieder aesthetic, encoded in a cycle like Winterreise (the greatest outburst from a poetic wanderer in musical literature) or in a song like Schubert’s “Der Einsame” (The Solitary One), with its chirping crickets and cozy hearth, its retreat from the world; but it misses out on a whole range of dramatic and theatrical possibilities in the singing of the lied, and ignores a tradition that goes right back to the first singer of Schubert’s songs, the distinguished but superannuated opera singer Johann Michael Vogl.

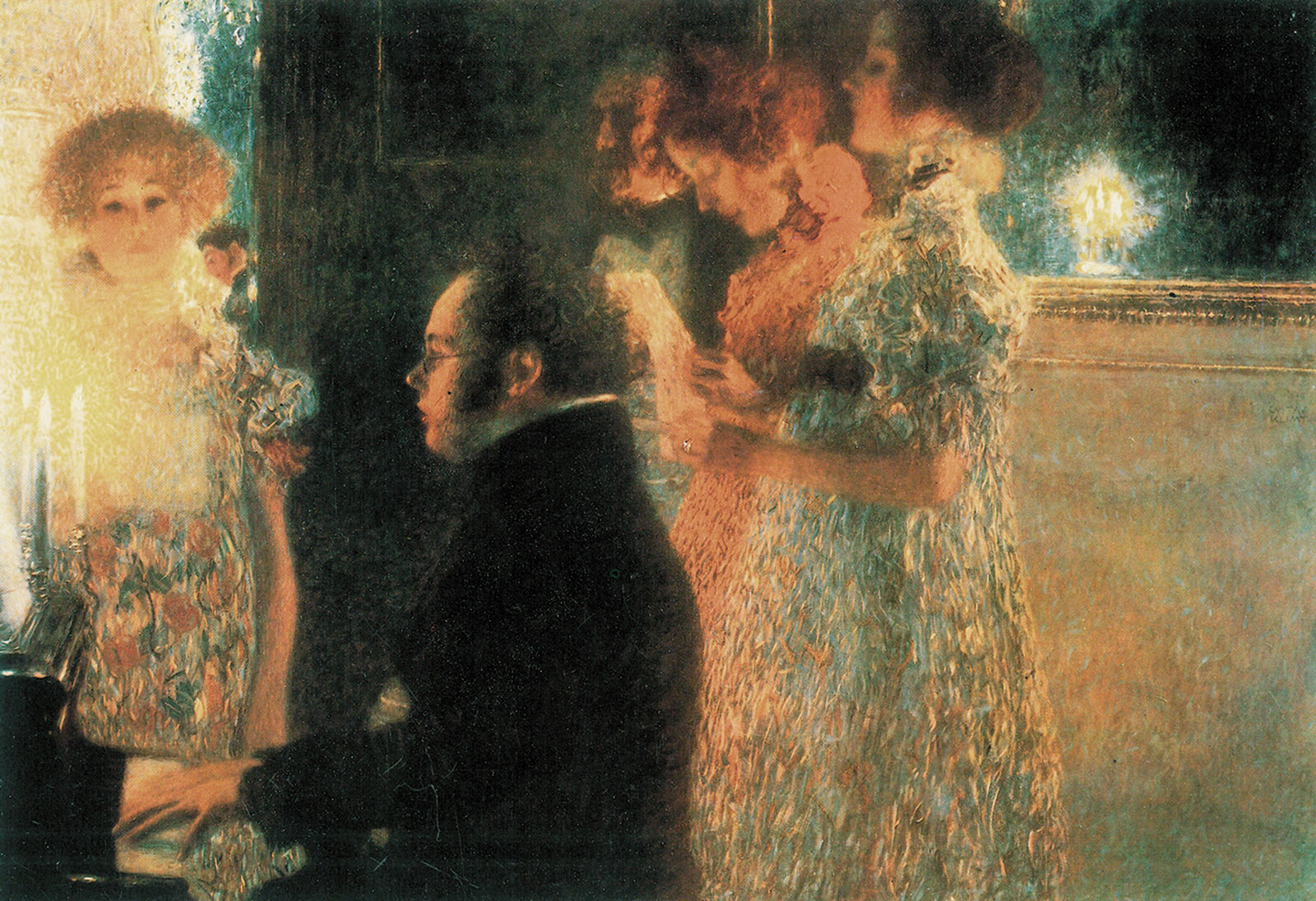

Disagreements among Schubert’s friends after his death over how to sing his songs point to a distinction between Vogl’s dramatic intensity and the noble melodic amateurism of someone like the Freiherr von Schönstein, the dedicatee of Die schöne Müllerin. Schubert clearly valued both: “The style and the manner in which Vogl sings and I accompany,” he wrote, “so that at such a moment we seem to be one, is…utterly new and unheard of.” In my experience as a singer, different songs require different approaches; indeed, the same song can demand something different depending on circumstances (where it comes in the program, how the audience seems, how the hall is constructed). Ultimately there is the freedom of the performer in the moment, who cannot be entirely constrained by the written instructions of the composed text, however detailed.

The notion of authenticity that haunts Benjamin’s essay extends to the art of performance, and is all about presence and aura. But the word “authenticity” also has a particular and slightly different resonance in lieder singing, demanding an affect that is usually defined in opposition to that of opera: glow and not glitter, real feeling, simplicity, sincerity. Add to this the absence of the body to which the gramophone accustoms listeners (and which Cardus celebrated in his review) and the increasing demands of perfectionism that the introduction of tape editing from the 1950s onward elicited, and you have a very particular sort of lieder singing that does not always fully engage with the blood, sweat, and tears that so often animated the songs of Schubert and his successors.

While the gramophone reclaimed lieder for the drawing room and reasserted the genre’s intimacy, it deepened the divide between amateur and professional, intensifying a process that had started with the genre’s move into the concert hall in the mid-nineteenth century and continued with the increasing complexity of songwriting for piano and voice in the works of Mahler, Wolf, and Strauss. If song as transmitted by the gramophone or wireless was peerlessly intimate and sincere, it was also increasingly a consumable commodity, as it was in 1929 for Rebecca West, who described listening, alone in the dark, to a broadcast of Elisabeth Schumann singing lieder as “the ultimate luxury.” It was Thomas Mann, in The Magic Mountain (1924), who most eloquently expressed the gramophone’s status as a conveyor of commodified spirituality, “an overflowing cornucopia of artistic pleasure” that could transmit that wondrous chimera, “the German soul, up-to-date.” Mann also put his finger on the disembodied quality that recording lent to musical performance:

The singers…[Hans Castorp] listened to, but could not see, had bodies that resided in America, in Milan, in Vienna, in Saint Petersburg—and they could reside where they liked, because what he had was the best part of them, the voice, and he valued this purified form, this abstraction that still remained physical enough to allow him real human control, and yet excluded all the disadvantages of too close personal contact.

What Mann further highlighted in his novel were the cultural roots of lieder in the birth of a German national idea and its consequent contamination with the curse of German nationalism. At the height of German nationalist fervor at the outset of World War I, Mann had notoriously, in his Gedanken im Kriege (Thoughts in Wartime), lauded German Kultur (deep) over Anglo-French Zivilisation (superficial), asking how “the artist, the soldier in the artist [could] fail to praise God for the collapse of a peaceful world with which he was fed up, so completely fed up.” “The entirety of Germany’s virtue and beauty,” Mann had declared, “unfolds only in war.” Bismarck himself, the Iron Chancellor, had not long before invoked the “power of German song as an ally in wartime.”

When, ten years later, Mann came to criticize the nationalism he had espoused and dignified, one particularly famous lied formed the centerepiece of his renunciation. This was the fifth song of Winterreise, “Der Lindenbaum” (The Linden Tree). A recording of “Der Lindenbaum” is Hans Castorp’s favorite in the sanatorium to which he has semivoluntarily retreated, and what draws him to it is, ultimately, the same force that draws him to the sanatorium, and that drew Mann and his compatriots toward their disastrous infatuation with war. “What was this world that stood behind” the song, “which his intuitive scruples told him was a world of forbidden love? It was death.” When Castorp marches forward to join the “worldwide festival of death” in the last pages of Mann’s novel, “he uses what tatters of breath he has left to sing to himself.” He sings “Der Lindenbaum.”

By the time of Lehmann’s farewell recital in 1951, the lied was, in many ways, deeply unfashionable. Born in the early nineteenth century as classicism was mutating into Romanticism in music, the genre had grown to maturity under the maximalist regime of late Romanticism. Further intensification of emotional agitation and harmonic coloring had culminated in an expressionism that was essentially a glorious dead end.

The sentimentalism and Romantic idealism that had been at the heart of the German song tradition had no place in the new aesthetic world that came into being just before World War I; the horrors of that war only heightened demands for emotional detachment and the spirit of Neue Sachlichkeit (new objectivity). In music it meant the twin poles of twelve-tone music under the aegis of Schoenberg and neoclassicism under that of Stravinsky. Stravinsky’s friend the eccentric amateur Lord Berners wrote in this period (dated 1913–1918) a telling setting of one of the most popular of Heine’s poems, “Du bist wie eine Blume” (“You Are Like a Flower”). The piano part is marked “secco (schnauzend)”—dry (snuffling)—and Berners provided a note for the song:

According to one of Heine’s biographers, this poem was inspired by a white pig that the poet had met with in the course of a walk in the country. He was, it appears, haunted by the thought of the melancholy fate in store for it…. The present version is an attempt to restore to the words their rightful significance, while at the same time preserving the sentimental character of the German Lied.

Lied composition had come to seem retrograde, reactionary, even ridiculous; and it is striking that Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs were so valedictory in tone, in title, and in timing, three years after the destruction of the German nation and a year before Strauss’s death. Their primary existence as orchestral songs also distanced them, through a warm glow of strings, from the mainstream of the piano-accompanied lied. But if creative energy had been sapped, the performance of lieder, a German art form par excellence, survived and even thrived. The anti-German prejudices of the Great War and its immediate aftermath were replaced by the interwar internationalism that ultimately triumphed in 1945, and the performance of lieder came, according to Tunbridge, “to represent pluralism and open-mindedness in the face of fascism.” Nowadays it is not Berlin or Vienna that is the capital of the song recital, but London and its Wigmore Hall, which last season mounted something approaching a hundred of them, dominated by German song. An art form “akin to a musical refugee” in the anxious 1930s, as Tunbridge puts it, has, through the vicissitudes of technological change and ideological turmoil, found its place.

This Issue

August 16, 2018

The ‘Witch Hunters’

The American Nightmare

The Queen of Rue