On the first page of The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border, Francisco Cantú uses the phrase “broken earth” to describe the parched ground beneath his feet. It’s an appropriate expression with which to open his account of policing the US–Mexico borderland—an area that the writer Gloria Anzaldúa has described as “una herida abierta,” an open wound, “where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.”1

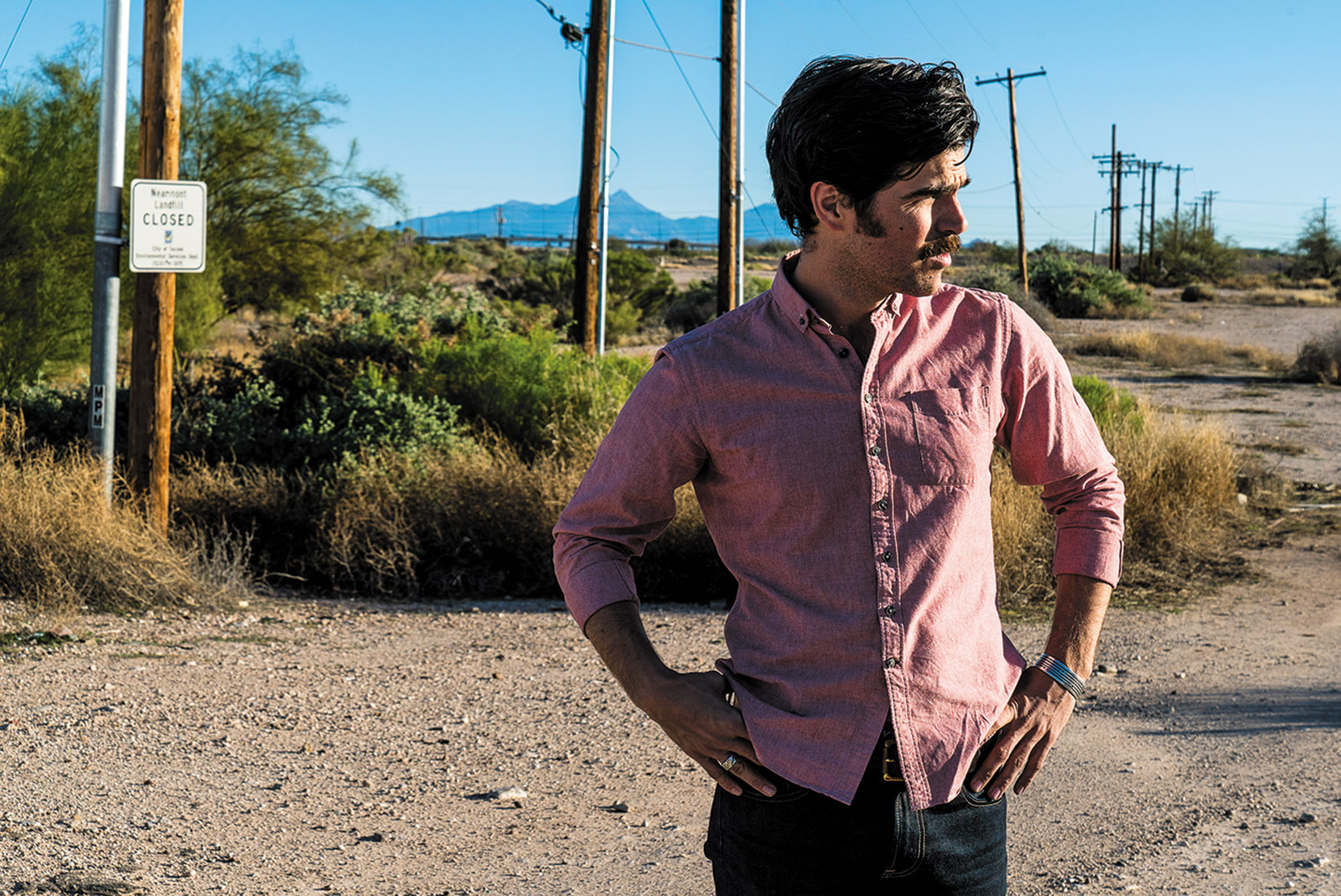

Cantú is from a mostly Mexican family. He was born in Arizona to a mother who worked as a park ranger and feels a deep connection to the landscape, fauna, and charisma of frontier country. In 2008, against his mother’s counsel, he decided to serve the state in a different way: by joining the Border Patrol. He told her he was tired of reading books about the border and wanted to have a part in its story. During his training, he writes, he was shown lurid scenes of torture and execution by Mexican narco cartels, and told, “This is what you’re up against.”

It becomes clear early on that the Border Patrol agents are not really after major drug traffickers. Cantú’s supervisor warns him, “You don’t want to bring in any bodies with your dope if you can help it. Suspects mean you have a smuggling case on your hands, and that’s a hell of a lot of paperwork.” As a result, as Cantú later tells a friend, “We mostly arrested the little people—smugglers, scouts, mules, coyotes….Mostly I arrested migrants, I confessed. People looking for a better life.” Cantú comes across no serious narcos and only one young man who wants to sell heroin in single doses to make a buck. By and large Cantú and his colleagues arrest people who, as they tell him, just “want to work” in America.

The Line Becomes a River is the story of the four years Cantú spent patrolling. The first of the book’s three parts recounts his daily experiences on the beat. Cantú’s fellow agents indulge in “senseless acts of defilement” and recreational vulgarity:

[Agent] Hart giggled and shouted to us as he pissed on a pile of ransacked [migrants’] belongings….It’s true that we slash their bottles and drain their water into the dry earth, that we dump their backpacks and pile their food and clothes to be crushed and pissed on and stepped over, strewn across the desert and set ablaze.

There is a motive here: “The idea is that when they come out from their hiding places, when they regroup and return to find their stockpiles ransacked and stripped, they’ll realize their situation, that they’re fucked, that it’s hopeless.”

Other abuses are less purposeful: Cantú’s colleagues set cacti ablaze in the dry desert for the hell of it; they laugh at stories about the self-mutilation of sexual organs two of them encountered during previous lives as a prison guard and a soldier in Iraq. A reviewer for Mexico City’s Excelsior wrote that Cantú’s book exposed “ex-soldiers playing at war but with easier targets: unarmed men, women and children.”2

The action takes place on land that Cantú and the other agents share with a native tribal police. Though Cantú does not say so, this can only be the Tohono O’odham reservation, which spans the border: the O’odham is the only Native American nation in the US to have Mexican citizens on its tribal council. The Border Patrol is charged with cutting its ancient terrain in two. I know this place. I wrote my book Amexica while Cantú was in the Border Patrol, criss-crossing the frontier in 2008 and 2009 to research Mexico’s narco war. Perhaps Cantú was one of the agents who constantly peered through my car window in the maze of checkpoints that line the border.

Reading Cantú’s account reminded me of the scathing words I heard from the tribal activist Mike Flores, with whom, one suspects, Cantú’s mother might sympathize: “They come from Texas, South Carolina, and they don’t know jack shit about this land,” he told me beside a fence between the US and Mexico that cuts across his ancestral land. “They act the tough guy, but if you put any of ’em out on the land under the sun without their toys, they’d be dead in two days.” As are so many of their quarry.

Cantú is part of this, but apart from it. He is from the “broken earth,” not Texas or South Carolina; he is educated; there is a heavy-hearted softness in his dealings with those he arrests and whose language he speaks—notably a Mexican couple cowering in a church, whom he turns in even though the woman is pregnant. That scene prepares us for the book’s more meditative second section, during which Cantú becomes increasingly aware of the suffering his work causes for the people he apprehends.

Advertisement

Cantú arrests a woman who was abandoned by smugglers after her foot was injured. At the wheel of his vehicle, he feels “a strange and familiar sense of freedom, an old closeness with the desert,” but looks at her in his rearview mirror, in the caged detention area, as she surveys the same scene with “no sense of freedom.” He has nightmares and finds it hard to look his mother in the eye; one night, he writes, “I stared into the mirror, trying to recognize myself.”

Part Three opens with Cantú, no longer an agent, working in a coffee shop alongside a new friend, José, who returns to Mexico to visit his dying mother after twenty years in the United States and gets arrested for crossing back without proper papers. Cantú does all he can to help José’s wife and sons as his friend enters the brutal labyrinth of criminal and civil immigration law to which Cantú had condemned so many but had never encountered directly. He finds himself “finally seeing the thing that crushes” and “driven to make good for the lives I had sent back across the line.” José’s case to remain with his family is denied, and he is deported.

After José makes another attempt to cross back and reunite with his family, his wife Lupe is shaken down for $1,000 by a stranger who promises to return her husband (it never happens). This is a cruel development along the border: whether or not this stranger was connected to them, narco cartels and criminal syndicates have become increasingly involved in human trafficking. Cantú notes that in one of the worst massacres on the Mexican side of the line, at San Fernando, Tamaulipas, the victims were not drug traffickers but migrants, mostly from Central America, who were thought not to have paid sufficient cuota to their cartel smugglers.

Cantú becomes immersed in Mexico’s extreme violence: he reads up on the serial abduction, violation, torture, and murder of women in and around Ciudad Juárez; mutilations by the narco cartels intended to convey specific messages to their enemies and the populace; and “disappearances” reportedly at the hands of the Mexican army. By this time, Cantú is working for the Border Patrol’s El Paso sector in Texas, where the line actually does become a river: El Paso sits across the Rio Grande from Juárez, which was, between 2009 and 2011, the most dangerous city in the world. Yet Cantú recalls that when he took a trip to Juárez in his youth, his mother twisted her ankle and fell, and something happened more characteristic of its citizens than violence. A man alighted from his truck to help, and when Cantú thanked him, he replied, “It’s nothing. In Juárez we take care of one another.”

This may seem weird in a city of bloodletting, but it’s true, and important. I reported in Juárez during the so-called femicidio—murder of women—and later throughout its worst tribulations with narco violence, while Cantú was across the river serving as an agent. I return frequently; it was where I spent last New Year’s. Only one firework was set off; the streets in a once-famous party town were empty by ten at night; and twenty-four people were murdered during the first two days of 2018, the worst start to any year since 2009–2011, when violence there peaked. But still, friendly strangers look you in the eye and enjoy an unnecessary chat, especially about soccer. At the border, the darker the shadows fall, the brighter its colors seem to shine.

Cantú’s book has already acquired a controversial history. Publishers Weekly reports that he thought it “might draw ire from his former employer and conservatives. He never imagined, though, that it would draw a backlash from the group that now seems to be railing against the title: liberals.”3 The New York Times found Cantú “unwilling to look too closely at his complicity in despicable behavior.”4 At San Francisco’s Green Apple Books, a reading was interrupted by people taking turns to speak about atrocities committed by the Border Patrol. At BookPeople in Austin, Cantú was heckled, “You profit off the murder of innocent people!,” and he was called a “traitor.” He tweeted: “To be clear: during my years as a BP agent, I was complicit in perpetuating institutional violence and flawed, deadly policy. My book is about acknowledging that.”

More extended discussions of the book have taken place on Frontera List, an open forum run by Molly Molloy, a librarian at New Mexico State University at Las Cruces who is quoted in Cantú’s book. The forum collates articles and other material useful to people for whom the border is a matter of passion and profession. In a post responding to the book’s hostile reception among liberals, Molloy argued, “It’s very important to learn the truths about this agency that Cantú was able to see from the inside.”

Advertisement

Molloy is right: the law gives some protections to whistleblowers who testify to the horrors of institutions that once employed them—who bring what they know to light—and perhaps there should be some equivalent allowance for memoir. Cantú’s account is a refreshing counterpoint to the glut of narco-thrillers and action-movie fantasies about US agents taking out drug dealers in Mexico. His disillusion with the agency he joined is total, his dismay at the system of border control is sincerely felt, and his book is a valuable contribution to the literature on what has become an increasingly scalding issue in the Trump presidency. Cantú’s story has deep roots too in American and Mexican history: death, detention, and deportation on the border.

The terrain from which Cantú writes is savage and breathtakingly beautiful: a vast desert that confronts you with boundless distances, fallen branches, and shed snakeskins brittle as parchment. This is where the Mexica, better known as Aztecs, came from (their lore called their home Aztlán). Astride what is now the border, Apaches and Comanches fought with Spanish- and English-speaking Europeans; this is where Pancho Villa rose and Zorro rode, and where the largest number of fighters defected to an enemy in US military history—Irishmen to Mexico in 1847, during the Mexican-American War. The frontier was gouged, as Cantú recounts, a year later by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which gave the United States what is now California, Nevada, and Utah, most of Arizona, and half of New Mexico, establishing the western section of the border in approximately the form that exists today.

The frontier is both porous and harsh; there is as much that binds as divides the lands north and south of the line. Every day, a million people cross the border legally, to work, visit family, or shop. For those who have papers, it takes minutes to walk from Matamoros to Brownsville, Juárez to El Paso, Piedras Negras to Eagle Pass. The economy of families along the borderline is international: residents buy electronic goods in the US, pastries and medical services in Mexico. The “twin cities” that face one another over the line are interdependent: Alex Perrone, a former mayor of Calexico, California (where the Trump administration is building one of its first new walls), who was born in Mexicali, Baja California, once spoke out against a proposal to line a canal on the US side with cement, to prevent Mexican farmers from tapping seepage. “Economically,” he said, “if Mexicali loses, we will watch Calexico die.” Sam Vale, a businessman in McAllen, Texas, whose Mexican grandmother sent her dresses by steamship to Paris for cleaning, told me, “McAllen lives or dies on the basis of international trade, starting with the fact that 90 percent of retail in the town is Mexicans coming over to buy stuff.”

More commercial traffic crosses the US–Mexico border every year than any other border in the world—five million trucks and tens of thousands of freight train wagons, worth some $400 billion. Starting in the 1960s, sweatshop factories (maquiladoras) were built along the border to produce goods that could be exported tariff-free to the US. The factories drew millions of people from the poor Mexican south and interior, not to cross the border but to live on it. This was three decades before the North American Free Trade Agreement removed trade barriers between the two countries in 1994.

For people in Mexico trying to cross into the United States, however, the border has become increasingly restrictive. When I first came to the Tijuana border in the 1980s, crossing it was a spectator sport. So-called “roadrunners” darted at dusk along a dry canal into the territorio de nadie, the no-man’s-land between Mexico and California, trying their luck by relying on strength in numbers. A 1994 offensive launched by Bill Clinton, called Operation Gatekeeper, ended this practice. In 2010, while Cantú was incarcerating migrants, Arizona governor Jan Brewer signed Senate Bill 1070, which empowered any law enforcement agency to stop any person and demand proof of immigration status, on pain of arrest and deportation if there was none. In hindsight, President Clinton’s measures were the genesis of the present draconian border policy that has developed over the past few administrations and has reached its most extreme form under Trump.

Even before Trump made it a cornerstone of his presidential campaign, the border was militarized. More than six hundred miles of fencing already existed, and are now being fortified and extended in places. The frontier is secured by guard posts, searchlights, infrared cameras, and sensors, and policed not only by the Border Patrol and Customs and Border Protection, but also by members of the National Guard, ICE, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, as well as SWAT teams. Trump, unsatisfied with these measures, has further brutalized immigration, asylum, and border policy. What the present White House calls “a bottom-up review of all immigration policies…dangerous loopholes, outdated laws, and easily exploited vulnerabilities in our immigration system”5 has resulted in policy that intensifies what Cantú calls “the thing that crushes.” In addition to Trump’s pledge of a “big, beautiful border wall”—which would cut not just across the land but through indigenous and environmentally protected lands—the president wants $100 million to recruit five hundred more agents to the Border Patrol, currently some 19,000 strong, as a “first hiring surge for the 5,000 [extra] agent requirement.”

Thousands of people who have lived peacefully in the United States for decades are being arrested and deported for the original sin of having arrived in the first place. Children are being incarcerated and separated from their parents. When Cantú is called in by his supervisor to translate for two children, aged nine and ten, who have been brought across by “friends” from Sinaloa, he tries to speak to them, but “they were too young, too bewildered, too distraught at being surrounded by men in uniform.”

I remember meeting in a shelter for deported children in Nogales, Sonora, around the time Cantú served, a four-year-old named America who had been dumped into the deportation pen by Border Patrol agents. She had no idea where her parents were, and sang a song from a telenovela series that went “Fiesta, fiesta, la vida es fiesta,” after which she burst into tears. That was during the Obama administration, yet it was nothing compared to what is happening as the Trump administration uses the detention of parents and children at separate, far-flung locations as a deliberate deterrent against asylum and migration.

The border is a place of paradox: it divides two nations but keeps them cheek-by-jowl, extends opportunities to some and consigns others to poverty. And paradox is what Cantú’s book is about: his own conflict as a Mexican-American who joined an apparatus dedicated to arresting Mexicans, and the deeper dichotomy that faces Latino US citizens on the border—what Cantú calls “the tension between the two cultures we carry inside us.” “Perhaps it is hard,” Molloy wrote on Frontera List, “for someone who doesn’t know the border to believe the contradictions that Cantú describes.” Cantú acknowledges the way the lights of El Paso and Juárez “reached across the border to form a single throbbing metropolis,” yet “to live in the city of El Paso…was to hover at the edge of a crushing cruelty, to safely fill the lungs with air steeped in horror.”

It is indeed strange to be, for instance, on the campus of the University of Texas at El Paso, among all that youthful effervescence, and look past the freeway at the shanty barrio of Lomas de Poleo, one of the poorest in northern Mexico, climbing a dusty hill not two miles away. I met a woman in 2002 in Lomas de Poleo called Paula González. She was holding the Virgin of Guadalupe necklace the police had finally recovered from the violated, mutilated body of her daughter María Sagrario, who had been dumped in the dirt. “Where were you,” she implored the icon, “when they did that to my little girl?” One morning six years later, I drove at dawn from the safety of El Paso to Juárez to find a crowd gathered at the sight of a decapitated body hanging by the armpits from an overpass.

Cantú eventually crosses the line to visit his friend José, who has been trying again and again to return to his family in the US and is torn between regret at having left them to visit his mother and the realization that he had no alternative. Once Cantú is across the border, one would have liked him to have ventured further and acknowledged the ways in which border-crossing has changed since he was an agent. Most of those whom Cantú intercepted when he was in Arizona would have left from the intimidating, cartel-controlled town of Altar, Sonora, a base camp for the treacherous journey north where every store and stall sold backpacks, flashlights, and other supplies for crossing from the village of El Sásabe into the US. When I was first there in 2009, almost all those staying at the Centro Comunitario de Atención al Migrante y Necesitado shelter were Mexican. But on a return visit in 2015, most were Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Guatemalans searching not only for work in the United States, but respite from gang violence back home, and seeking asylum.

This March, while Donald Trump visited the new border wall prototypes near San Diego, I was across the line at Tijuana’s most established shelter, Casa del Migrante. Back in 2008, during Cantú’s time in the patrol, most people there were Mexican; in 2015 they were primarily Haitians who had fled the ravages of the earthquake; this year, biding time in the green-and-cream-painted courtyard, most had fled gangland carnage in Central America or persecution and war in Africa, the latter group having arrived via Brazil. The recent outcry over the barbarity of family separations on the border highlighted how the proportion of those seeking to cross as asylum seekers, rather than so-called economic migrants wanting “a better life,” has increased since Cantú’s day—more than the administration seems prepared to recognize.

Parts of the border remain open in ways the Trump administration shows no intention of addressing. One is the “iron river” of southbound traffic in guns to the cartels: 70 percent of the 105,000 weapons seized by Mexican police between 2009 and 2014 came from the US, and that does not include the increasing number of arms assembled from smuggled parts. The other is the northward flow of drug money: the Wachovia and HSBC banks were caught, in 2010 and 2012, respectively, laundering profits made by the Sinaloa Cartel. Bank officials were given deferred prosecutions—no one went to jail—but someone is still cleaning narco money north of the border, and the system that permits this is becoming more opaque.6 So despite all the “flawed, deadly policy” Cantú was tasked with enforcing, a steady supply of cocaine, heroin, and meth still crosses the border at a stable price while violence in Mexico spreads and worsens. And if Mexicans are now wiser to the perils of crossing the border in pursuit of “a better life,” countless others are sufficiently desperate to try.

For them, the border has become an insurmountable obstacle. At one point, Cantú’s friend José admits, “I would rather be in prison in the US and see my boys once a week through the glass.” Often, crossing on foot from Juárez to El Paso, one observes people doing so in tears—probably returning from visits to those like José. “There are thousands of people just like him,” writes Cantú, “millions actually—the whole idea of it is suffocating.” When he lived and worked in Texas, José would stare at a satellite image of his mother’s house on a computer. After he crossed the frontier to her deathbed and became stuck on the Mexican side, José confides to Cantú, “I look out the window at those hills….That’s the United States. I used to be able to just run up and over those hills. But now there is a barrier. I hate it, I hate it.”

This Issue

September 27, 2018

Aquarius Rising

Missing the Dark Satanic Mills

Tenn’s Best Friend

-

1

Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (Aunt Lute, 1987). ↩

-

2

Leo Zuckermann, “Los Horrores de la Patrulla Fronteriza,” Excelsior, March 22, 2018 (my translation). ↩

-

3

Jason Boog, “Border Patrol Agent-Turned-Author Meets Protests in California,” Publishers Weekly, February 23, 2018. ↩

-

4

Lawrence Downes, “A Different Perspective on the Border,” The New York Times, February 27, 2018. ↩

-

5

“President Donald J. Trump’s Letter to House and Senate Leaders and Immigration Principles and Policies,” White House press release, October 8, 2017. ↩

-

6

“Wachovia Enters into Deferred Prosecution Agreement,” press release by the US Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida, March 17, 2010. ↩