1.

A year ago, the remains of Liu Xiaobo were scattered in the Yellow Sea. Over the decades, many gallant Chinese have spoken up for individual rights and government accountability, but Liu stood out for his systematic critique of China’s government, as well as his moderation and advocacy of nonviolent protest. It is no wonder that he was awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, or that his death was an enormous loss for China’s ziyoupai, or “freedom faction.”

The sense of helplessness among Liu’s supporters was compounded by the grotesque series of events that led up to his death from liver cancer. The authorities had constantly assured the world that he was being treated fairly. Yet he was only transferred to a guarded hospital ward a month before he died—presumably to avoid the charge that the regime had allowed a Nobel Peace Prize winner to die in prison. Foreign doctors were brought in, but only in his last few days. The government released strangely voyeuristic videos and photos showing his painfully distraught wife, the artist Liu Xia, at his bedside. After Liu died, his estranged brother, who years earlier had allied himself with the Communist Party, was shown thanking the party and saying that everything possible had been done.

Most of this was for foreign consumption. Domestically, the flow of information was more controlled. Liu’s prison issued a few terse statements on his illness, care, and death, but his thoughts and writings are impossible to find through any normal channel. A year later, despite the release in July of Liu Xia to Germany, one can argue that Liu is a nonperson in China—of interest only to a few thousand dissidents. One might imagine that when they die, he too will die in the public memory, commemorated only by foreign human rights groups and studied by academics interested in turn-of-the-century Chinese thought and politics.

And yet memory can be miraculously persistent. This is a major theme in Blood Letters, an important new biography of Lin Zhao, the journalist who was executed fifty years ago this spring for criticizing the Communist Party’s misrule in the 1950s and 1960s. After years of imprisonment, torture, and mental deterioration, she was hauled out of the prison hospital where she had shriveled to seventy pounds, taken to a thousand-seat prison auditorium in her hospital gown, gagged with a rubber ball, sentenced to death, and shot. Her mother learned the news from a messenger; a few days later, law enforcement demanded from her five cents to cover the cost of the bullet.

Sustained by her Christian faith, Lin wrote hundreds of thousands of words in prison, but all were confiscated and locked away. Yet her writings somehow survived and slowly spread, despite censorship. Today she is counted as one of the most remarkable dissidents of the Mao era, one whose reputation grows by the year.

In the 1980s, admirers and family members found her ashes and buried them at Lingyan Hill outside her hometown, the eastern city of Suzhou. Her grave has become one of the most visited pilgrimage sites for China’s human rights activists. Every year on April 29, the anniversary of her death, the area is locked down; the rest of the time it is guarded by closed-circuit television. The existence of Lin’s grave may have caused authorities to scatter Liu’s ashes at sea.

How did such a person become a threat to the regime? Thanks to Lian Xi, a professor at the Duke Divinity School, we now have a clearer answer. Blood Letters is one of the most important books on the Communist-era rights movements to be published in recent years. It is not only the first biography of Lin in English, but also the first in any language to carefully sort through the sometimes overwrought and polemical writing inspired by her martyrdom.

Lian’s earlier works have been about Christian history in China, most notably Redeemed by Fire (2010), which shows how the indigenization of Protestantism in the first part of the twentieth century helped create a dynamic religious movement that remains the most persistent challenge to government control. This background helps him understand Lin’s anti-Communist fervor. He read the more than 500,000 characters she wrote in prison, as well as her earlier writings, and tracked down her paramours and classmates. He also talked to the judge who reviewed her case in the early 1980s as part of a reckoning with the excesses of the Mao era. His highly readable, deeply informed book portrays someone who rediscovered her faith under the pressure of persecution and used it to create a body of writing that today exemplifies resistance to Maoist-era persecution.

2.

Born Peng Lingzhao in 1932 in the prosperous city of Suzhou, Lin was educated in a Methodist mission school, where she learned hymns and prayers by heart. In her teens, however, she converted to communism, blindly believing the party’s promises of equality and justice, and remolding herself into a good Communist. She stopped going to church and distanced herself from her family. Her father had been a minor official in the Kuomintang government, which had lost China’s civil war to the Communists in 1949, while her mother had run a small bus company, making her a capitalist. The daughter broke with them by changing her surname Peng to Lin and shortening her given name to Zhao.

Advertisement

She ran away from home to join a propaganda team and participated in the Communists’ bloody campaign against small landholders. Between one and two million were killed—the minor officials, scholars, medicine practitioners, and religious clergy who formed the backbone of traditional society. Lin didn’t spare her family either: she denounced her father for listening to Voice of America and her mother for allegedly being backward. Her father was later labeled a “historical counterrevolutionary,” and her mother attempted suicide.

But Lin had an independent streak that she couldn’t repress. She criticized male cadres who took advantage of young women—a common occurrence in Maoist China—and became frustrated in love because she wanted to ask men out and not wait modestly for them to approach her, as was expected of proper women according to the party’s puritanical morality. Most troubling for the party was her refusal to give it absolute obedience. In 1949 it ordered her to leave her hometown, feeling that she was in danger, but she refused, thinking that it was being overly cautious, and she was stripped of her party membership.

After the People’s Republic was founded in October of that year she was still trusted enough to be assigned to a newspaper, where she was charged with bringing independent reporting to heel. A few years later, she was allowed to apply to Peking University. She had one of the highest scores on the entrance exam in the country and was admitted at age twenty-two to the Chinese department.

Even though Lin suffered from tuberculosis, she was active and popular at Peking University: her many admirers saw her as a modern Lin Daiyu, the fair and frail heroine of China’s most famous novel, Dream of the Red Chamber. Well educated in classical Chinese, she edited the poetry journal, delighted in reciting ancient texts, and also enjoyed ballroom dancing. As one of her friends later recounted in an article: “Wearing a wreath made of the flowers she picked, she entered the ballroom and would dance to its very end.”

But her independent spirit soon got her into more trouble. In 1957 the party launched the “Hundred Flowers” campaign, which encouraged people to offer criticisms of it. Ostensibly a way to help the party improve its performance, the call for criticism was really a trap. Two of Lin’s friends fell for it and offered a critique in the form of a poem that they pasted on a wall. That spurred a mass protest by Peking University students against bureaucratism and high-handed party officials, as well as broader issues such as the party’s monopoly on truth.

The party’s counterattack against such protests was known as the Anti-Rightist Campaign. Hundreds of thousands of educated people were purged from schools, research institutes, government offices, and enterprises for criticizing the party. It marked a formal end to any sort of tolerance that the new government had for alternative viewpoints and unleashed a twenty-year period of totalitarianism that ended with Mao’s death in 1976.

Lin naively came to her friends’ defense, writing her own poem criticizing the party’s defenders: “The power of truth/never lies in/the arrogant air/of the guardians of truth.” She was not arrested, but she sympathized with the Rightists, thinking that the party had become cruel and unbending. She had several romantic affairs, and knew of plans that some had to flee China to set up a democratic base abroad. She was declared a Rightist for her role in defending these government critics and sentenced to three years of “reeducation through labor.” This could have meant a labor camp, but because of her tuberculosis—by then she was coughing up blood—she was allowed to work on campus.

It was at this time that Lin broke with the party and returned to her Christian roots. She resumed attending church and openly described herself as a Christian. Her fiancé warned her against being too headstrong, saying it was like smashing an egg on a rock. Her answer was typical of her unbending character: “I have to strike it. If thousands upon thousands of eggs strike against it, this hard rock will be smashed.”

Advertisement

Eventually, her fiancé was assigned to a labor camp in China’s far west, and Lin went to Shanghai, where her mother lived, to seek medical treatment. There she heard about a group of students in western China who had been exiled for their beliefs. She mailed them a copy of “Seagull,” a prose poem that dispensed with the subtleties and classical allusions that typified her earlier work. “Seagull” was a call for freedom and opposition to Mao and his reign of violence:

The tyrant wields his sword and rod, and puts us on trial,

because he fears freedom just as he fears fire.

He is afraid that once we find freedom,

his throne will be shaken, his fate will be dire.

One of the students was so excited by her poem that he traveled to Shanghai to meet her. By then she had already completed her most famous poem, “A Day in Prometheus’s Passion,” a 368-line account of the Greek myth. In it, Zeus is a torturing bully, but Prometheus’s opposition leaves the great god nervous and defensive:

“But you ought to know, Prometheus,

for the mortals, we do not want to leave even a spark.

Fire is for the gods, for incense and sacrifice,

how can the plebeians have it for heating or lighting in the dark?”

The students in western China had been alarmed by the economic problems caused by the government crackdown. Mao’s Great Leap Forward (1958–1962) created the worst famine in history, with tens of millions dying. In 1960 they published A Spark of Fire, a journal of essays and secret documents revealing the unfolding catastrophe. Lin Zhao’s poem was the longest single piece in what turned out to be the journal’s only issue.

Authorities swiftly arrested the group, including Lin. She was released in 1962 on medical parole due to her tuberculosis and after she temporarily curbed her criticisms of the party. After the famine, moderates briefly sidelined Mao, and Lin was hopeful that change was afoot. But once out on the street, she saw that the party hadn’t changed. She packed her clothes and informed neighborhood police that she was ready to be taken back to prison.

The party soon obliged, and later that year she was again before a judge, charged with “counterrevolution.” She argued that the term was meaningless, and that “the real question,” as Lian writes, “was not what crimes her generation…had committed against the ruler, but what crimes the ruler had committed against them.” She was so blunt that the judge asked, “Are you sick?”

In fact, her mental health was precarious, which is unsurprising given her solitary confinement and mistreatment. The most common form of torture that she and others suffered was handcuffing, with the arms pulled behind the back and the handcuffs tightly fastened, leaving the inmate unable to eat, dress, or use the toilet without help. Inmates like Lin often had to lick their food off the floor and soil their trousers. Some cuffs were so tight that the shoulders would be damaged and the flesh of the wrists would rot, leaving permanent marks. At times, prisoners would beat Lin, or guards would pull out her hair.

For these final six years of her life, Lin didn’t leave prison. But she kept writing, mostly on paper with ink. When she was denied writing implements or when the issue was urgent, she wrote in her own blood. She would sharpen the end of a toothbrush by scraping it on the floor and then prick her finger, collecting the blood in a spoon and then writing with a sliver of bamboo or reed. Sometimes she wrote on scraps of paper, other times on her clothing.

As Lian points out, her writing is direct, angry, and shorn of nuance. Most famously, she wrote a 137-page letter to the Communist Party’s mouthpiece, People’s Daily. She also used blood to paint an altar on her prison wall in honor of her father, who had committed suicide after his arrest in 1960. She later added an incense burner and flowers, and from 9:30 AM to noon each Sunday she held what she called “grand church worship,” singing the hymns and saying the prayers she had learned in the Methodist girls school.

Like other single-minded dissidents—Liu Xiaobo, for example—Lin often gave little thought to the suffering her obstinance caused her family. Her mother received a stipend of only twelve yuan a month, but Lin bombarded her with requests for blankets, food, and supplies. Lin’s unwavering opposition also turned her siblings into political pariahs, and her brother chastised her as “the most selfish person in the world.”

But this focus came from her conviction—which would surely have seemed delusional to anyone who knew her at the time—that her writings would last. In 1967 she described a recent 30,000-character batch of blood letters that she had sent to her mother in this self-confident way: “In the future, they will make up yet another volume of either my complete published works or a posthumous collection of my papers.” Who could contemplate in these circumstances that her works would be published? None of her letters reached her mother, let alone People’s Daily. But prison guards didn’t destroy valuable evidence against this enemy of the state and the writings stayed in her ever-expanding file.

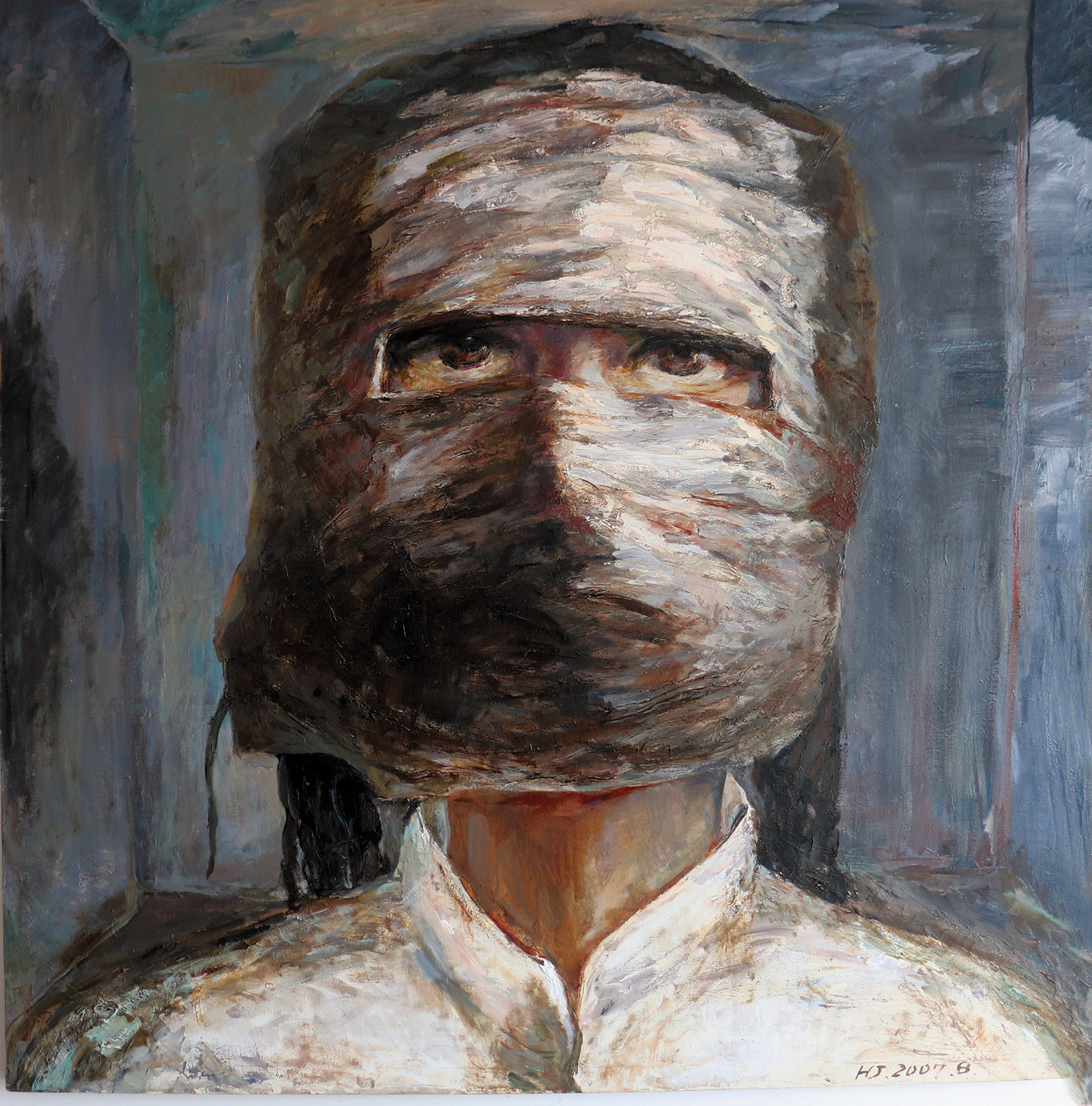

Her death in 1968 came during the extremism of the Cultural Revolution, when the state decided to kill especially unrepentant critics. When her death sentence was passed, she was made to wear a “Monkey King cap”—named after the mythical Chinese hero who was so uncontrollable that he had to wear a band around his head that could be contracted to bring him to heel. In this case, it was a huge rubber hood with a slit cut for the eyes and a hole for her nose. The hood was only removed at mealtime.

When she was executed on April 29—a few days before the big May Day celebrations—her family’s fate seemed sealed. Her mother slid into mental illness. She tried to commit suicide by throwing herself in front of a trolley but ended up with a gash on her head and a broken pelvis. Her son became unhinged too, and beat his mother. She died in 1975.

Mao’s death in 1976 ended the Cultural Revolution. Slowly, information about Lin began to come to light. In 1979 Peking University formally lifted the charge against her of being a Rightist. Later, the Xinhua news agency held a memorial service for her.

The judge who reviewed Lin’s file decided to release much of her writing to her family in 1982. This didn’t include official court documents, but did include sheets of manuscripts, numbered and bound with green thread, and four notebooks of diaries, as well as ink copies of her blood letters home, which Lin had copied so they would be preserved for posterity. Lian interviewed the judge, who said he was impressed by her poetry and felt it should be delivered to her family, but that the original blood letters were “too much for the raw nerves.”

In the early 2000s, Lin’s friends and fiancé edited her writings, and they slowly spread online. One of the first dissidents to discover them was Ding Zilin, the mother of a Tiananmen massacre victim. A fellow alumna of the Methodist school in Suzhou, Ding found Lin’s letters to be revelatory, writing that they were “a kind of redemption for my soul.”

Most important was a documentary by the artist and filmmaker Hu Jie.* Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul (2004) tells her tale through interviews with those who knew her. Hu’s film has disappeared from Chinese websites, but it remains important for many Chinese dissidents. Liu Xiaobo praised her, as did the prominent rights lawyer Xu Zhiyong, who called her “a martyred saint, a prophet and a poet with an ecstatic soul, the Prometheus of a free China.” Or as the well-known writer Cui Weiping put it, because of the discovery of Lin Zhao’s writings, “we now have our genealogy.”

3.

How does Lin exist for some Chinese but not for others? How can dissidents know of her, while most people remain ignorant?

To understand this we have Censored, a new book by Margaret Roberts, a professor of political science at the University of California at San Diego. It provides the clearest and most convincing explanation of how information is controlled in today’s China. This is especially valuable because most ideas about censorship in China rest on fundamental misunderstandings.

Although we might imagine censors as drudges wielding big red pens to strike out offending words, responsibility lies with millions of editors, curators, directors, producers, and ultimately with the creators themselves: writers, artists, and musicians. They know what is off-limits and exercise self-censorship, from topics such as the Tiananmen massacre to routine issues such as trade disputes, territorial claims, or urban redevelopment. Those writing on these issues must be aware of the party’s viewpoint or face punishment. In some cases, they do submit works to a censor for vetting, but mostly the censor sits in the creator’s head.

As for consumers, Roberts says they are controlled through “friction” and “flooding.” As she puts it, censorship in China is primarily a “tax on information, forcing users to pay money or spend more time if they want to access the censored material.” This means that information—say, a website with Lin Zhao’s writings—might be inaccessible in China. But someone determined to access it could buy a foreign virtual private network, or VPN, which allows the person to access the uncensored Internet, or perhaps try a free VPN—most of these are blocked in China, but determined people can keep trying until one finally works.

This is the friction that makes it hard to access information. The flooding makes available so many alternatives—not just entertainment but government-approved versions of history—that they will satisfy most people. If you are a student at Peking University and wonder who Lin Zhao was, there is an entry on Baidu Baike, a government-approved version of Wikipedia. It is fairly factual and describes her case as typical for intellectuals during the Anti-Rightist Campaign, and if you searched that event, you would find that it was a regrettable period of extremism for which the party has long since made amends and distanced itself. Most people probably wouldn’t search much further.

One of Roberts’s important insights is that people aren’t willing to pay much for information, either in time or money, unless it is immediately pertinent to their lives. So when the government wanted to push Google out of China in 2010, it did so by making the search engine appear to malfunction by not allowing it to load 75 percent of the time. By contrast, Baidu Baike was speedy. For all but the savviest of users, it simply seemed that Google didn’t work. Use of Google plummeted, and it left China.

A major advantage of this policy is that most people aren’t aware of it. This drives a wedge between the elites and the masses, who are too busy and generally uninterested in politics to search for banned material. “By separating the elite from the masses,” Roberts writes, “the government prevents coordination of the core and the periphery, known to be an essential component in successful collective action.”

But this doesn’t mean that efforts to access this information are pointless. It’s inconceivable, for example, that Baidu would have such a substantive if incomplete article on Lin Zhao were it not for Hu Jie’s documentary or the publication of Lin’s works online. While most people cannot see either, elites in China can, making it impossible for Baidu and other government-endorsed information outlets to pretend that Lin didn’t exist.

This is why it’s wrong to think that no one knows about Liu Xiaobo and his terrible death a year ago. Many people have paid the price to learn about his fate. Last year, scores of people memorialized him on the beaches of northern China: they waded out into the water, lit candles, took selfies, posted them online, and went to jail to show that they hadn’t forgotten.

Inevitably, these commemorations will became less frequent, making it easy for some to say that Liu is irrelevant to most Chinese. But like Lin and her memory, Liu’s will continue to attract people devoted to the protest of one upright person. And one day, when the definitive histories of this era are written, they will be part of it.

This Issue

September 27, 2018

Aquarius Rising

Missing the Dark Satanic Mills

Tenn’s Best Friend

-

*

See my “China’s Invisible History: An Interview with Filmmaker and Artist Hu Jie,” NYR Daily, May 27, 2015. ↩