In June 1885 Henry James received a letter from John Singer Sargent in Paris asking him to see two friends of his who were coming to London. One was Dr. Samuel Pozzi, whom Sargent had painted in a red dressing gown in 1881, “a very brilliant creature”; the other, Sargent wrote, was “the unique extra-human Montesquiou of whom you may have heard [Paul] Bourget speak with bitterness….(Take warning and do not bring them together.)” There was a third man in the group: Prince Edmond de Polignac, a composer.

James devoted July 2 and 3 to entertaining these three gentlemen. “Montesquiou is curious, but slight,” James wrote to a friend. On the second day, he invited Whistler to join the group. Even for James, who was intrigued by the lines that connect art and life, history and literary history, it would have been strange indeed had he realized that he was in the company of the man on whom Baron de Charlus in Proust’s In Search of Lost Time would be based, that beside him was the doctor who would be used in the making of Proust’s Dr. Cottard, and that Proust would become a friend of Polignac’s once he was introduced to him by Montesquiou in 1894.

There is a wonderful encounter in Proust’s Within a Budding Grove, as the narrator is walking close to the zoo with the Swanns, when an old lady “smiled at us with a caressing sweetness.” Swann takes him aside to explain that they are in the presence of the Princess Mathilde, a niece of Napoleon I and friend of Flaubert and Sainte-Beuve:

And the whole person was clothed in an outfit so typically Second Empire that—for all that the Princess wore it simply and solely, no doubt, from attachment to the fashions that she had loved when she was young—she seemed to have deliberately planned to avoid the slightest discrepancy in historic colour, and to be satisfying the expectations of those who looked to her to evoke the memory of another age.

The encounter, and what the princess had to say for herself, have an aura of pure, distilled reportage. The princess belonged to many kinds of history that fascinated Proust. She herself was aware of how recent the Bonapartes were, reminding others: “Without the French Revolution, I’d be selling oranges on the streets of Ajaccio.” Proust referred to her as “my first highness.” Flaubert had replied to her in 1867 when she asked, “Who ever thinks of me?”:

All those who know you, Princess, and they do more than think. Writers, people whose job it is to observe and to feel, are not stupid! I also observe that my close friends, the Goncourts, Théo [Théophile Gautier], father Beuve and I are not the least devoted among your entourage.

This sense of a past, filled with shadows and intricacies, before his own past began to fill up with them too, gives this passage in Proust’s novel its particular intensity. The writing and the quality of the observation seem natural, arising from a moment that had never been forgotten, until we notice a letter written in 1915 from Proust to Lucien Daudet, son of the novelist:

You, who saw the Princess Mathilde when you were very little, must describe one of her costumes for me, a spring afternoon, the crinoline-like dress she wore in mauve, perhaps a hat with streamers and violets, just as you must have seen her, in fact.

Courtesy, thus, of the weird, ironic art of fiction, characters can travel to London and have supper with novelists, who have other novels on their mind, before they are fully imagined and put firmly in their place by later novelists. And Proust, the arch-rememberer, can write to a friend to help him describe a scene that he would render so closely that it seemed fully real, but instead was imagined all the more intensely because that was what was required in his novel just then.

In Monsieur Proust, Céleste Albaret, who was Proust’s housekeeper, wrote about the relationship between the characters in his novel and the people they were based on:

I’d say that fundamentally he was as little concerned about the keys to his work as about the keys to his apartment…. And so what difference did it make if the character of the Duchess de Guermantes was based partly on Countess Greffulhe, and partly on Mme. Straus and the Countess de Chevigné, and partly on ten or a dozen others? In a hundred years, what would it matter that anyone should know this, and who would remember these ladies? But the Duchess de Guermantes and the other characters would still be alive in his books and in the eyes of new generations of readers.

Albaret, however, goes on to speculate about the use that her employer made of the Countess de Chevigné:

Advertisement

What he took from her for his Duchess de Guermantes were her bearing and her clothes; the graceful neck and the carriage of the head he took from Countess Greffulhe. The duchess’ wit was more that of Mme. Straus. He used to draw a clear distinction in talking about the three models.

Caroline Weber’s Proust’s Duchess is an exhaustive, engaging, brilliantly researched account of who these three women were and how they each, in different ways, created an allure that so fascinated Proust. It is also a portrait of Paris in a time when it was still unclear to a select group that the French monarchy might not somehow return, when privilege and an elaborate set of manners and systems of social behavior were still fully in place so that a small breach in them could mean either social doom or a reputation for brilliance and originality.

It is also a book that throws considerable light on Proust’s method as a novelist by letting us see the sheer amount of information available on these women: where they came from, where they went each season, what their husbands were like, what lovers they had, what their disappointments and hopes were. It allows us to see more starkly how Proust’s method works, how little he was concerned with the actual minutiae of infidelities and love affairs and secret trysts, how he allowed the reader to take these for granted, and how much, on the other hand, he was intrigued by what was visible in a single moment in a room, at a gathering, how many generalizations he could make from a single glimpse or glance or change in the social air.

He was concerned with manners as a painter might be interested in shade or contrast, as a composer might be interested in melody. And he was fascinated by the sensibility of his narrator, his desires, his ways of remembering, his close and fragile ways of noticing, registering, sifting evidence, and studying what lay on the surface, seeing what people wished to reveal of themselves when they appeared in the social world. Proust then made music from this, being more interested in music than gossip, and only tangentially inspired and nourished by actual tittle-tattle about rich women in a confined quarter of a changing city.

His aim, at the beginning, however, was not clear to his friends. One of them remembered: “In those days, Proust seemed much more determined to get invited to certain aristocratic houses than to devote himself to literature, and this preference made no sense to us.” In Jean Santeuil, the unfinished precursor to In Search of Lost Time, Proust wrote about men of letters who sought to infiltrate the grand salons:

Seldom are the[se] men of letters as naively snobbish as the world makes them out to be. When [such a man goes into society] he does not say to himself: “I want to arrive, I want to be sought after in the monde…” No, [he] says to himself: “I want to feel everything, experience everything…. In order to be able to depict life someday, I want to live it.” (Still, this rationale does not impel him to seek out poverty…, which just as much as opulence qualifies as a form of life.)

“In the middle of Paris,” wrote Princess Bibesco, who married into this realm, it “formed a world as distant from ordinary people on the streets as the moon is from the earth.” As a doctor’s son with a Jewish mother, Proust came from the earth. And, more than anything, as he wrote about the moon, he found drama in the possibility that his narrator could so easily be banished from it, or would miss the point of a moment that would be casually clear to everyone else. Weber quotes Proust’s friend Fernand Gregh:

Back in 1890 or so, Proust’s birth barred him, or at least he believed that it barred him, from the Faubourg…. When he was first starting out in society, Proust saw the Faubourg as a forbidden realm; and that is why he dreamed of it with such passion, the way a child who collects postcards or stamps dreams of Tahiti or Ceylon. And like the early cartographers of Africa, Proust filled this terra incognita with roaring lions and birds of paradise. The lions, for him, were the men, all those noblemen with their celebrated names…; the birds were the women.

The first woman whose salon Proust entered was Geneviève Straus (1849–1926). She was Jewish, the daughter of a composer. She married the composer Georges Bizet in 1869; he died of a heart attack six years later. Their son, Jacques, was a school friend of Proust’s. Indeed, when he was seventeen, Proust made his feelings for Jacques clear to him: “Still, it saddens me not to get to pluck that delicious flower while we still can, because if we were to pluck it later, by then it would have ripened into—forbidden fruit.”

Advertisement

In the years when Geneviève was married to Bizet, she lived in the same building as her cousin the writer Ludovic Halévy, and this house became, Weber writes, “a favorite gathering spot for artists in the area,” including Degas, Turgenev, Massenet, Gounod, and Fauré. Besides cultural figures, Geneviève was also interested in people with money. Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, who had been a patron of her father’s, later noted: “It’s incredible, every time there is a Rothschild anywhere in sight, Geneviève just has to latch on to him!”

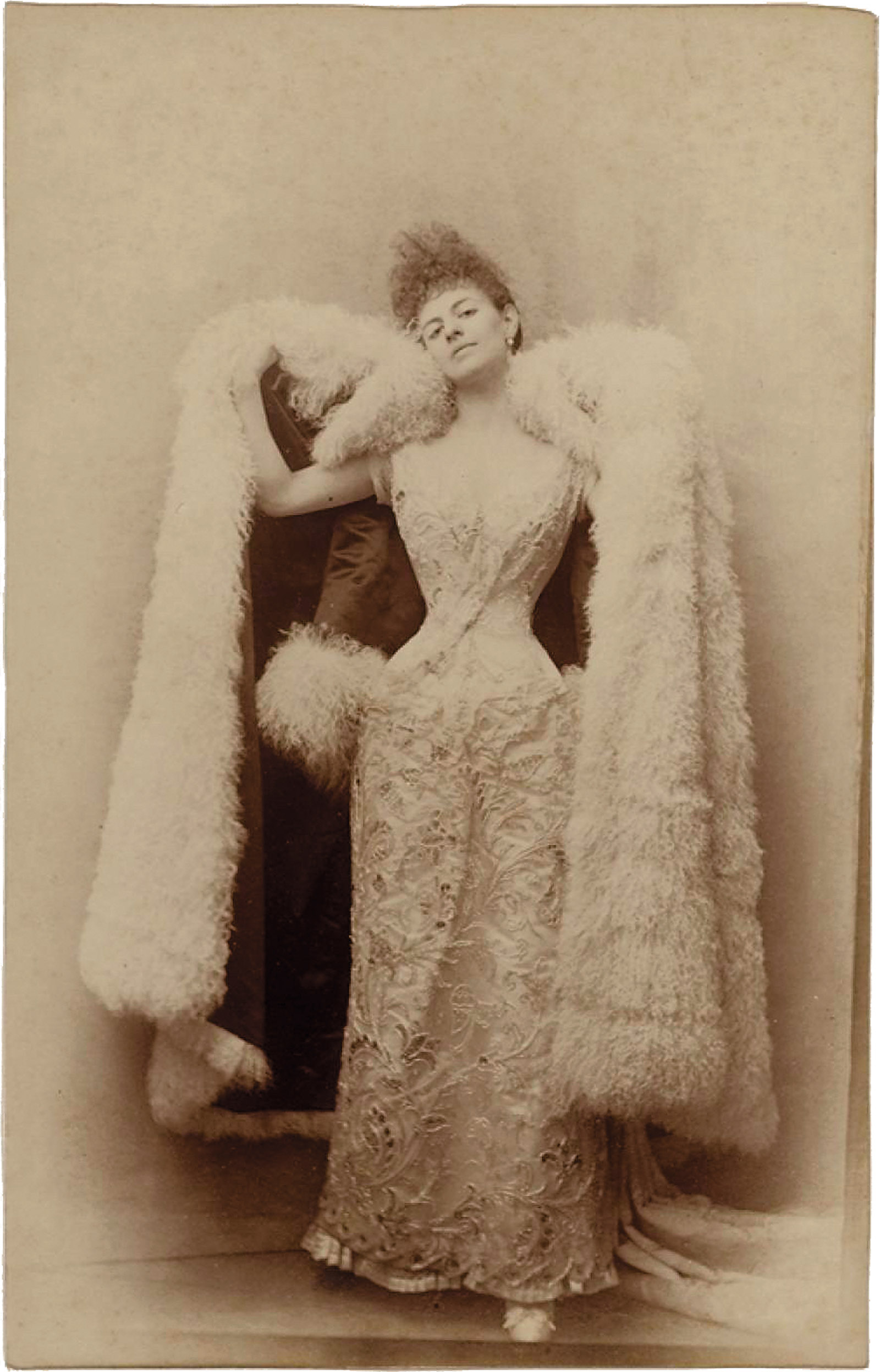

After Bizet’s death, Geneviève gave what Weber calls “a committed performance” as his grieving widow. She was still wearing black two years later (longer than was customary) “when she sat for a portrait by her friend Élie Delaunay. With her permission, Delaunay showed the painting at the 1878 Salon de Paris: a haunting study in black veils, black clothes and sorrowful black eyes” (see illustration on opposite page). For three years more, Geneviève continued to wear black. But even though the world believed her to be in deep mourning, her nephew, also a friend of Proust’s, remarked that “she wasn’t a lonely widow for a single day.” In 1881, she began to see the lawyer Émile Straus, whom she married in 1886.

The salon she then created was a mixture of the artists she had known when her husband was alive, the Rothschilds, and whatever members of the social elite she could gather. In other words, the bohemian and the well-born got to see one another at her house. They included, for example, a young poet and a general who had fought on different sides of the barricades in 1871: “Yet the young poet and the old soldier interacted cordially at Geneviève’s, modeling harmony between their respective camps.” At the beginning, Geneviève encouraged the writers to bring new work:

She sometimes even recited a few poems or sang a song or two herself, with Gounod or Massenet accompanying her on the piano…. But over time Geneviève reduced the cultural heft of her salon, having gleaned from her patrician friends that speaking earnestly about highbrow topics violated the monde’s basic requirements for elegant conversation (that it remain lighthearted) and womanhood (that it exclude bookishness).

Princess Mathilde was often accompanied by Edmond de Goncourt, who, while he did not appreciate the number of Jewish guests, appreciated the conversational tone that Geneviève encouraged: “amusing and frivolous, as in an eighteenth-century salon—full of finely malicious double entendres, and barbs like scornful smiles.”

Fernand Gregh wrote: “Everything Proust knew about the monde, he learned at Mme Straus’s.” What he learned first was that it did not do to talk about books or ideas there. In The Guermantes Way, Proust wrote that the Duchess de Guermantes never sounded as “literary, to my mind, as when she spoke about the Faubourg Saint-Germain, and never seemed to me more stupidly ‘Faubourg Saint-Germain’ than when she spoke about literature.” During his first dinner party at her house, the narrator discovered that “when she was with a poet or a musician, she found it [more] elegant to converse with them about the weather” than about their work. “To the uninformed visitor, there was something disturbing, even mysterious, about this abstention,” and above all when it included “a celebrated poet he had been dying to meet.” So, too, at Geneviève’s salon, as Weber writes, “like an aristocrat’s feigned indifference to lineage, her disregard for genius accentuated her inborn right to take it for granted.”

In this world, Proust had to repress his own sharp mind. Later he recalled:

A youth stands a better chance of succeeding in [the monde] if he is dull rather than intelligent…. I was very young in that milieu. At first I only said the silliest things. One day, I spoke intelligently. I was banned from [smaller gatherings] for six months, and only invited to the [bigger] crushes.

“The longing,” Weber writes,

to see the monde from within shaped not only Proust’s sexual persona but his manners more generally. When studying Mme Straus’s upper-class friends, he did not content himself with remarking upon their overweening investment in matters of form. He observed the myriad, subtle shadings of speech and deportment that characterized their interactions.

It mattered, of course, that their talk was silly, with little flashes of wit, but with no real content. Proust did not have to bother listening to these people too much. Their ways of moving were more interesting, as were their habits and their origins, their elaborate systems of gathering, with all the inclusions and exclusions. What they did not say became one of his subjects. He was not a diarist, but someone interested in texture and tone. He had no interest in telling secrets. Instead, it was how close the surfaces seemed to something deeply secret that engaged his imagination.

What he really needed was to immerse himself in the world of these people as though it mattered. It was his genius not to see their idleness as vacuous, or their manners as absurd, or their social life as empty, or their presence in Paris as filled with urgency as the life of dinosaurs in the time after dinosaurs. He saw what he could do with them. That is why he sought to get close. Despite his efforts, however, they made sure that he kept his distance. When Proust tried to encourage Robert de Montesquiou to introduce him to Élisabeth Greffulhe, he responded: “Do you not see that your presence in her salon would rid it of the very grandeur you hope to find there?”

There is an interesting letter that Proust wrote to Geneviève Straus before The Guermantes Way appeared, letting her know that he had “incorporated the red shoes” into his narrative. George Painter writes in his biography of Proust:

It was Mme Straus who once put on black shoes instead of red when dressing for a fancy-dress ball, and like the Duchess [de Guermantes] was compelled by her angry husband to change them; but it was in no such circumstances of cruelty and selfishness: Proust ran upstairs to fetch the red shoes, and all was well.

This scene as fiction is one of the most disturbing in Proust’s novel: Swann has arrived to let the Guermantes know that he is terminally ill, but they, needing to get to a ball, make light of this, and then have to rush. They cannot be late, until the duke discovers that his wife is wearing black shoes rather than red and makes her go and change, declaring, “But we have all the time in the world!”

Since Weber has done so much research, she can pinpoint the evening Geneviève Straus was wearing a red dress: March 2, 1892, when, decked out as the Queen of Hearts, she went to a costume ball with Proust and others. Since Swann is “based” on Charles Haas, who was not dying in 1892—he lived for another decade—Weber writes:

Nonetheless, another of Geneviève’s most devoted, longtime friends, composer Ernest Guiraud, did pass away at fifty-five just two months after the ball. It is thus not out of the question that Guiraud showed up…on the evening…with tidings akin to Swann’s. And if one considers Proust’s theory that Geneviève didn’t “care a whit” about other people—or [her nephew] Daniel Halévy’s observation that she was “as egotistical as a monster and as unthinking as a doll”—it is not improbable that if Guiraud did try to tell her about his failing health, she reacted flippantly, in the manner of the future Mme de Guermantes. Whatever happened that night, it made a lasting impression on Proust, compounding his disenchantment with Mme Straus and accelerating his search for a new model of mondanité.

It is much more likely that, in real life, no man came that night in 1892 to tell Mme Straus that he was dying. All that happened was the episode with the black shoes and the red shoes. That was enough for Proust when he needed drama. The small real episode nourished the larger imagined one. The question of the shoes became, in Proust’s imagination, one of the great morally dramatic moments in his book, a moment he rendered with profound subtlety and care. He did not judge the Guermantes crudely for their haste; he made clear that this was what we all might have done, in one way or another, in the face of someone else’s death. Move on; become busy. He let us see what it looked like so we would know. It seems to me more likely that this brilliantly serious moment was merely caressed or helped into place by the small memory of the shoes.

While he bathed richly and regularly in this world of grandeur, Proust often needed very little to make a character. Jean-Yves Tadié in his biography notes that while Proust modeled the figure of Swann on Charles Haas, “it is surprising to discover that one of Proust’s main characters [Swann] was based upon a man whom he did not know very well.” This is helpful, perhaps, in reading Caroline Weber’s book, since two of her three “duchesses” were not close friends of Proust’s at all, nor did he spend much time at their salons. Instead, he found out what he could about them; and, as much as he was allowed, which was not much, he moved in their world. These two figures, more elusive and perhaps more beguiling than Geneviève Straus, are the ones mentioned by Céleste Albaret—Laure de Sade, Countess Adhéaume de Chevigné (1859–1936), and Élisabeth de Riquer de Caraman-Chimay, Countess Greffulhe (1860–1952).

Élisabeth’s wealthy husband, Henry, was interested in horses and also in mistresses whom he

bedded…daily, one after another in rapid succession, when he was in town. So punctiliously, in fact, did Henry adhere to this schedule that [his] horses…stopped automatically at each address on his daily route, without any prompting from the driver.

While he bought artworks and rare books, this was only for status. At dinner, his family, including his ghastly mother, talked about horses and other animals. Henry, who was a bully, saw Élisabeth’s interest in reading as a character flaw. She was thus a young, rich, lonely, bookish, and beautiful woman, in need of rescue.

Soon, feeling passionate about Élisabeth became all the rage in these inner circles. Even Prince Edmond de Polignac joined in. “His enthrallment with Élisabeth,” Weber writes, “was the most ardent emotion the gratin [the class about whom Proust wrote in The Guermantes Way] had ever seen him display; it was well known that his erotic tastes did not run to women.”

Laure de Chevigné, the next “duchess,” was descended from both the Marquis de Sade and her namesake, Laure, beloved of Petrarch. Her family was royalist. While Élisabeth was refined, Laure was wild; she used rough words and took up smoking. In 1879, she married Count Adhéaume de Chevigné. From a minor branch of an old family, he was one of Henri V’s private secretaries, which might have meant something had Henri V ever ruled. Instead, “mildly cross-eyed, grossly fat, and lame from a long-ago riding accident…[and with] prodigious rubbery jowls all drooped in an attitude of permanent defeat,” the Bourbon pretender lived in exile at Frohsdorf in Austria, where his court was run with all the same protocol as though the Sun King were in residence.

Laure would base the subsequent allure that grew around her in Paris not only on her own ancestors, but on the fact that Henri V, who died in 1883, had seemed to enjoy her company, and had even made a drawing of her. After his death, the king-in-exile, whom few in France had ever actually met, was a subject of great reverence among royalists. Princess Mathilde Bonaparte called the fragrance she used after him. Princess Bibesco noted that Laure, as she fueled the pale fire of monarchist nostalgia, could “impose a poetic vision of herself on those around her, to reimagine herself as a new and fabulous character, and to project that character—her double, so to speak—into the mirror of the public imagination.” Proust, having found out where Laure lived, began to shadow her in the street until one day in the spring of 1892, when he was not yet twenty-one, she turned and glared at him and screamed that a man by the name of Fitz-James was waiting for her, a man rather grander than the young son of a doctor, however smitten.

Two years later, Proust would be introduced to Élisabeth Greffulhe. He wrote to Montesquiou, who was her relative (she called him her uncle): “The whole mystery of her beauty is in the sparkle, and above all the enigma, of her eyes.” Montesquiou, after Élisabeth’s marriage to the uncouth and philandering Henry, had become one of her confidants. He called her husband “the Big Blockhead.” Henry hated him in return.

Montesquiou was famous for his antics. As Huysmans described in À Rebours, he sent his pet tortoise to have its shell gilded and set with precious stones, which killed it. Among his possessions was the bullet that had killed Pushkin and the bedpan Napoleon had used after Waterloo. It was noted that “on a smooth, tapering forefinger he wore a large signet ring set with a crystal that had been hollowed out to contain a single human tear—whose, he never disclosed.” It was through Montesquiou that Proust would catch his glimpses of Élisabeth. In waiting for these so intensely, he saw enough of Montesquiou to be able to make use of him too when the time came to create the strange, irascible Baron de Charlus.

While Proust, once he had taken what he needed, got on with his work, his “duchesses,” all of whom outlived him, left letters and diaries. For example, Élisabeth Greffulhe’s “personal archive,” Weber notes in her acknowledgments, consists of “thirty-two linear yards’ worth of private writings,” some “developed on the basis of a nineteenth-century form of stenography.” This was created at a time when women in Élisabeth’s world still presumed that how they lived would matter in the future, little knowing that it would indeed, but by courtesy only of an interloper.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Weber writes, the French aristocracy “was dying as a political force while resurrecting itself as a myth.” The novelist Jules Renard wrote in 1898: “Since the Revolution, our republic hasn’t made a single step toward [equality] or liberty. It’s a republic where all people care about is being invited to [Élisabeth] Greffulhe’s.” As Weber notes: “Described by still another commentator as ‘the triumph of the duchesses,’ this contradictory state of affairs persisted for as long as mondain society did, only to collapse along with it in the chaos of the First World War.” In this artificial world, with all its flickering shadows, Proust watched as through glass, while the duchesses and their guests paraded inside, under the illusion somehow that they were fully real.