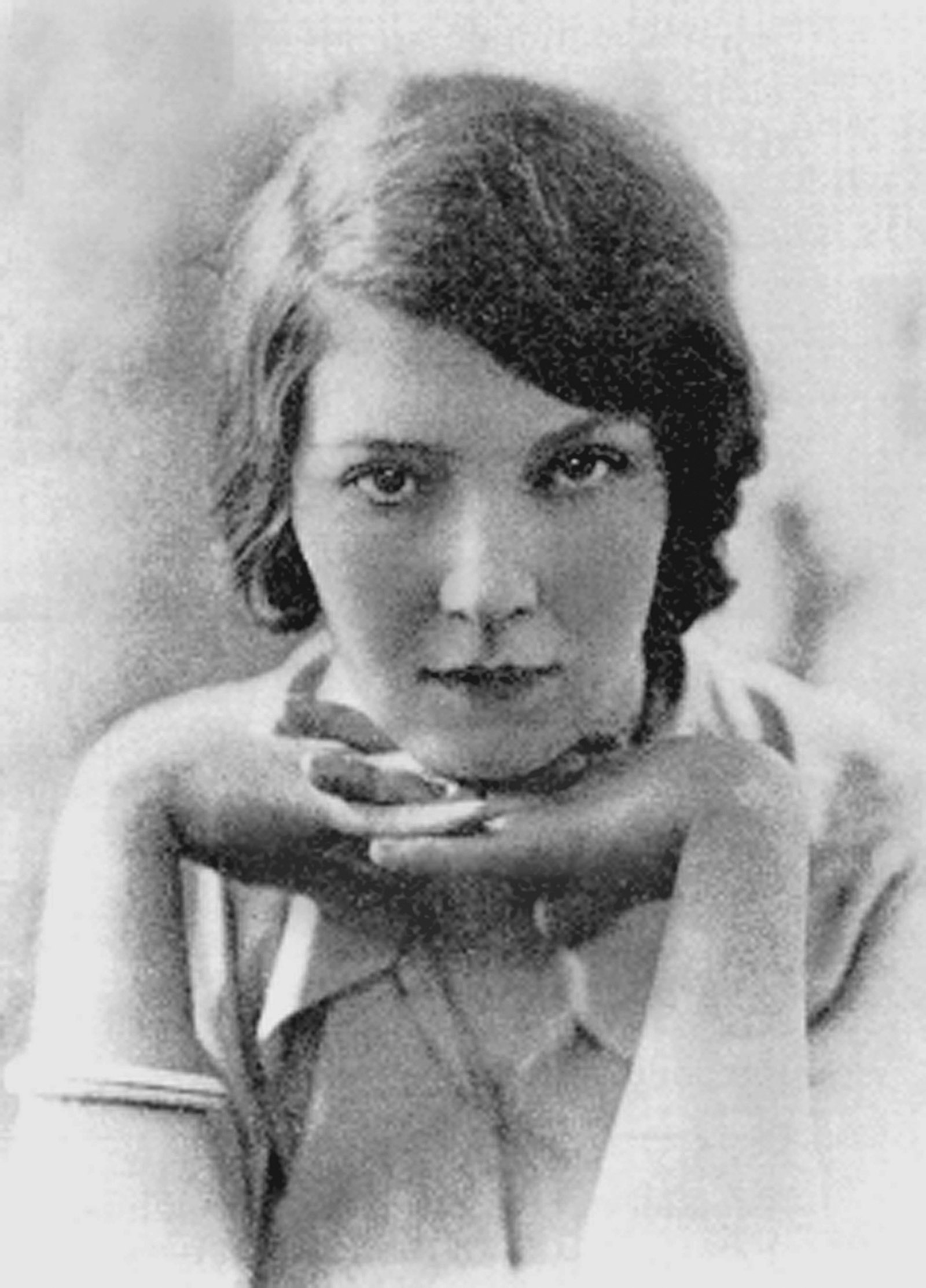

Few books have been as poorly served by their authors as the novels of Jean Rhys. The drinking (two bottles of wine a day, so drunk that she got violent, so drunk that she got stuck in the toilet), the poverty and the helplessness, the tangled affairs and the excruciating loneliness—the story of her life nearly eclipsed her talent. “Jean Rhys was not a modern woman,” wrote her biographer, Carole Angier. “From beginning to end, dependence was her way of life.” Born Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams in 1890 on the Caribbean island of Dominica, she moved in her teens to England, where she worked as a chorus girl, nanny, and prostitute. Men supported her throughout her life, especially her second husband, Leslie Tilden Smith. He typed up the writing she left scattered on pieces of paper around the house and reassured her of her genius even after she beat him up.

One summer during college, I read the four volumes of collected Paris Review interviews in order to learn how to be a writer (an exercise that was unsuccessful but that I nonetheless recommend). Rhys’s answers seemed so sad, so pathetic, so dreary: “I’ve never written when I was happy. I didn’t want to. But I’ve never had a long period of being happy. Do you think anyone has?… When I think about it, if I had to choose, I’d rather be happy than write.”

None of this prepares you for the pleasure of reading her novels. What’s extraordinary is how they seem so very alive. Part of this is the language Rhys uses, always simple, mostly short sentences, which add up to short books too. The collected volume I have, arranged by her editor Diana Athill, contains five novels interspersed with Brassai photographs that together come to about two thirds the length of Ulysses. Part of it is also the way that they’re constructed. I know of no other writer who uses so much first-person dialogue, which has a strange effect. Rhys keeps her “I” present and the other characters’ words too, so that reading, you’re not quite in a narrator’s head but not fully out of it either.

In Voyage in the Dark, for example, there’s a scene in which Anna Morgan goes to the house of the wealthy man about to take her on as his mistress. Anna has moved to London from the Caribbean after her father died. She is cold and lonely. Her stepmother cuts her off, so she joins a chorus and does what the other girls do: finds a man to support her. She is naive and needy enough to believe that this might be love:

He was saying, “You’re perfect darling, but you’re only a baby. You’ll be all right later on. Not that it has anything to do with age. Some people are born knowing their way about; others never learn. Your predecessor—”

“My predecessor?” I said. “Oh! my predecessor.”

“She was certainly born knowing her way about. It doesn’t matter, though. Don’t worry. Do believe me, you haven’t got to worry.”

“Yes, of course,” I said.

“Well, look happy then. Be happy. I want you to be happy.”

In just a few lines Anna has learned that while he is her first love, she is not his, and that it’s not love at all. The entire scene is presented and digested in a flash.

Rhys started writing while living in a grungy room in a part of London called World’s End:

My fingers tingled, and the palms of my hands. I pulled a chair up to the table, opened an exercise book and wrote This is my Diary… I filled three exercise books and half another, then I wrote “Oh God, I’m only twenty and I’ll have to go on living and living and living.” I knew then that it was finished and there was no more to say.

She put the exercise books at the bottom of her suitcase. “Wherever I moved I took the exercise books but I never looked at them again for many years.” Later, when living in Paris with her first husband, Jean Lenglet, a Dutch musician and crook, she tried to sell a translation of his articles on Paris chansonniers and met a newspaper editor who asked if she couldn’t write instead. The editor rearranged the exercise books and sent them to Ford Madox Ford, who suggested that the young writer take up the pen name “Jean Rhys” and helped her edit her text for publication. They also began an affair.

Like nearly everything Rhys did, it was a bad idea. All four participants—including Stella Bowen, Ford’s common-law-wife, and Lenglet—later described the entanglement in books. No one appears to have had a good time. Worse, for Rhys’s work at least, was the way Ford described her writing. In his introduction to the The Left Bank and Other Stories, her first collection, he spent half a dozen pages recounting his own Paris experiences before casting her as a kind of helpless idiot savant. “Coming from the Antilles, with a terrifying insight and a terrific—almost lurid!—passion for stating the case of the underdog, she has let her pen loose on the Left Bank of the old World.” He praised her “singular instinct for form” possessed by “almost no English women writers.”

Advertisement

In fact, Rhys was an incredibly careful and painstaking writer. The control she was unable to show in her life she exerted on the page. It’s true that most of her stories were based on her own experiences, but she hated the idea that her work was largely autobiographical. It was far too sophisticated for that. In a section of her diary she kept in the 1940s while separated from her third husband, Max Hamer, she worries about her egotism. She imagines herself on trial, cross-examined by an unnamed prosecutor:

It is myself

What is?

All. Good, evil, love, hate, life, death, beauty, ugliness.

And in everyone?

I do not know “everyone.” I only know myself.

And others?

I do not know them. I see them as trees walking?

Rhys made up for her inability to invent with an almost fanatical devotion to structure, working and reworking her books so that they would in some way resemble reality. “The things you remember have no form,” she told The Paris Review. “When you write about them, you have to give them a beginning, a middle, and an end. To give life shape—that is what a writer does. That is what is so difficult.” She went over her texts endlessly to make the writing more simple, more lifelike. “I can write mediocre ‘poetry’ so easily, and labour so over prose. Then all traces of effort must be blotted out.” Her efforts are invisible, the triumph of her work.

One of the joys of reading Rhys’s novels back to back is watching her learn from one to the next. Her early ones are good but simple. The narrative in Voyage in the Dark is buoyed by a sort of naive guiltlessness. By Good Morning, Midnight, her second-to-last novel, Rhys has absorbed the tricks of modernism. She deploys them delicately to try to understand the effects of mistake and regret. Her subject is again a woman, alone, living in a series of depressing hotel rooms. Here she is Sasha Jansen, worn down by her mistakes, sitting around Paris hoping that a new dress, a new perfume, might turn her life around:

Saved, rescued, fished-up, half-drowned, out of the deep, dark river, dry clothes, hair shampooed and set. Nobody would know I had ever been it. Except, of course, that there always remains something…. Never mind, here I am, sane and dry, with my place to hide in.

The perspective moves over the course of the book closer to Sasha and then farther away. Like that in Voyage in the Dark, the writing is immediate and fresh. Unlike that book, there’s no backstory. We never learn where Sasha is from, where she is going. Details leach out: a failed marriage, thoughts of suicide. It is gradually revealed that Sasha had a child who died:

Do I love him? Poor little devil, I don’t know if I love him.

But the thought that they will crush him because we have no money—that is torture.

Money, money for my son, my beautiful son….

I can’t sleep. My breasts dry up; my mouth is dry. I can’t sleep. Money, money….

Where was he buried? Is his death the reason for the end of her marriage? (Rhys herself had a son who died as a baby from a combination of parental incompetence and active neglect.) These questions receive no answers. When the book ends, Sasha’s life is just as sad and alienated as it was before the book began. It simply continues outside our view, as the regret and remorse linger.

Wide Sargasso Sea was Rhys’s last novel and the one that is the most like a traditional story. It clearly has a beginning and a middle and an end, and other features readers look for in novels, like a plot and fleshed-out characters. It’s also the only one that seems to respond directly to any kind of tradition, instead of seeming, as Rhys often was, entirely alone and isolated.

By the time she wrote it Rhys was nearly forgotten. The interest generated by other modernists had largely eluded her. Aside from her relationship with Ford she had never been a part of any sort of group; she knew few people and even fewer writers. When an actress decided to adapt Good Morning, Midnight for a radio play in 1949, the producers assumed Rhys was probably dead. Entire years seem to have been lost to disarray or sickness. Still, she worked on Wide Sargasso Sea for twenty-one years thinking that “it might be the one book I’ve written that’s much use.”

Advertisement

It’s not hard to see why it made the splash it did. By telling the story of Jane Eyre’s mad woman in the attic, Rhys turns Brontë’s novel on its head. Bertha is not a cruel and weak hag but is named Antoinette Coswey, a guileless woman twisted by her husband’s power. Rhys’s Rochester is cruel, greedy, racist. He insults the Caribbean people he meets and denigrates them: “I was tired of these people. I disliked their laughter and their tears, their flattery and envy, conceit and deceit.” His behavior is heartless and controlling. He sleeps with other women in the bedroom he shares with his wife. He changes her name in order to exert his will over her although she pleads for him to stop. “You are trying to make me into someone else, calling me by another name.” Rochester doesn’t care if he destroys his wife’s fragile sense of self. He has already taken over her estate. “I saw the hate go out of her eyes. I forced it out. And with the hate her beauty. She was only a ghost.”

When the events of Brontë’s book finally appear in the third and final part of Rhys’s, the clash feels exultant. It is exhilarating to see so clearly what Jane blindly accepts in acquiescing to Rochester. (It’s easy to forget that the last words of Jane Eyre are not “Reader, I married him” but “Amen; even so, come, Lord Jesus!”) Rochester puts his wife in the attic, where she is given thin gray clothes and disgusting food to eat. Alone save for the company of the alcoholic servant Grace Poole, she wonders where she has been held captive. “It was that night, I think, that we changed course and lost our way to England. This cardboard house where I walk at night is not England.” She burns the cardboard house down as Rhys, a woman rejected by her chosen country, slips into its literary tradition and sets a fire too.

Late success brought little happiness. The hotels Rhys stayed in were nicer but she still spent most of her time drinking. She tried to work on a memoir, later published as Smile Please. (She wanted to call it And the Walls Came Tumbling Down.) The form didn’t suit her. She complained that “all of a writer that matters is in the book or books. It is idiotic to be curious about the person. I have never made that mistake.” She died before it was finished, though I don’t think that’s the only reason the book reads less vividly than her other works. In her will, she asked that no one write her biography.

A View of the Empire at Sunset by the British novelist Caryl Phillips bills itself as a novelization of Rhys’s life but it is soon clear that the woman at the center of the novel is not really Jean Rhys. She’s “Gwen,” “Gwennie,” or “that Williams girl,” Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams if she didn’t write. The book follows her Caribbean childhood to her arrival in England, her first two marriages, and her trip with her second husband Tilden Smith back to Dominica, where she finds herself unwanted and unhappy. Like Smile Please, the book is organized in short vignettes with cryptic titles—“Anyone for Tennis?” “Suede Gloves in One Hand.” The episode with Ford, Rhys’s obsession with literary form and structure, and the disappointing responses to her novels are all elided. “Her island had both arranged and rearranged her, and she had no words,” Phillips writes, denying Rhys the one reason she felt she had “earned death.”

Rhys unstitched Brontë to show a Caribbean view of Britain. Phillips continues that tradition, taking her life as representative of the British Empire rather than the exception. Phillips moved to England from St. Kitts as a child and has used his books to explore the myopic imperialism of the British, who exploited the Caribbean and denied its residents any humanity. The Final Passage, his first novel, tells the story of a young woman who leaves the Caribbean with her son to find a better life and must make do with the dreariness of England: “The rivers that the bus lurched over were like dirty brown lines, full of empty bottles and cigarette ends, cardboard boxes and greying suds of pollution.” In Cambridge, a white woman travels to the West Indies to visit her father’s plantation and sneers at the people she meets there. (“I have heard several reports…that the black is addicted to theft and deceit at every opportunity.”) Phillips’s novels rewrite British history to integrate the history of its colonies. There has never been, he shows us, the white, isolated nation in which so many British people seem to believe.

Phillips’s Gwen recedes into the England she encounters, a grim place. “London appeared to be comprised of little more than endless rows of houses boxed tightly together so that it would be logical for any newcomer such as herself to assume that English people lived like yard fowl in small coops.” The girls at her boarding school call her “West Indies” and mock her accent. “Tell me honestly, do you even have a mother or were you hatched from an egg?” asks one of the students she tries to befriend.

Gwen’s life proceeds in a series of disappointing affairs. There is no love in this England. She “learn[s] to fall asleep” next to one man but he never takes her in his arms. Another claims he cares about her, yet barely seems to know who she is. “Had he troubled himself to look closely at the young woman before him, he might have come to terms with the reality that this particular girl bore no resemblance to the shy English girl he actually wanted.” Even the smallest male gestures are threatening. One man unpins her hat and fills her with fear. “If he had taken hold of her dress and stripped it violently from her body she could not have felt more naked than she did in the wake of his gesture.” The only moment of affection is the dance of two workers at a pub, one of the best scenes in the book. They fall into each other, feeling the “cool calm of a familiar body.”

Gwen longs to return to Dominica. As she shuffles from one dark room to another, her thoughts are filled with the desire for home. “You said you were happy there once, so you will be happy there again,” a hapless Tilden Smith assures her, blind to the fact that the island has changed. When they finally arrive in Dominica, they are not welcome. A visiting white woman no longer has a clear place there. The few interactions she has with black people are awkward and patronizing. “If he maintained his distance she would, at the completion of her task, offer the Negro a handful of coins. Her father would, of course, have deemed it the right and proper thing to do.” She sits silently and looks at the water, contemplating her loss of position. “In an hour or two, as the listless waves continued to lap, she might witness the full glory of the sun rising over her now empty world.”

As Phillips reminds the reader, although she was white, Rhys was considered Creole in her lifetime because she was born in the Caribbean. (Ford claimed that “Creoles are as noted for their indolence as for their passion. On this basis, she became entirely comprehensible.”) Rhys was also the descendent of colonizers and had a privileged upbringing and status, something Phillips highlights. As a child, Gwen plays “native” with a black girl her parents employ as a servant in Dominica. Gwen is able to leave Dominica. Francine, the friend, cannot.

Phillips’s prose is often formal and distant. One of Rhys’s great skills was to strip her writing of emotion, so that the sadness she portrayed comes across as sharp and aggressive rather than sentimental. Phillips veers in the opposite direction: “She broke off a piece of her heart and gently dropped it into the blue water.” Here is Rhys’s description of her first English morning in Smile Please:

I lay for what seemed like an age. There wasn’t a sound but I wanted to see what London looked like so I got up, put on my clothes and went out. The street door must have been bolted, not locked, or perhaps the key was in the door. At any rate I got out quite easily into a long, grey, straight street. It was misty but not cold.

Phillips’s version of the same scene views it from a step away:

After a long, restless first night she eventually opened her eyes and saw the first light of the day beginning to stripe the corners of the curtains and decided that it was time to flee the imprisonment of the shared bed. She stepped down onto a small square of rug and quietly pulled on multiple layers of clothing before cautiously opening the bedroom door and silently making her way along the corridor.

The stiff tone creates its own form of alienation. You are always aware that you are reading Phillips’s version of Rhys, Phillips’s version of England.

Reviews of the book have argued that Phillips’s Rhys is not always fair to the real one. In Harper’s, Elizabeth Lowry noted that “Phillips’s Gwen visits the ruins of the old family plantation, which ‘ungrateful Negroes’ have burned down. ‘Why don’t they like us?’ she wonders. In its merciless exposure of the long-term damage of every kind of bondage, Wide Sargasso Sea shows that Rhys knew very well why they didn’t.” She is right, though I imagine that Phillips also knows this—you can’t read that novel without noting Rhys’s analysis. It makes up most of the book. A muted Rhys is a choice rather than a mistake.

Phillips’s real target is England itself. Black people have come to England for hundreds of years, but it has never wished to see itself as a nation of immigrants, as Phillips wrote in his essay “The Pioneers: Fifty Years of Caribbean Migration to Britain.” For most of its history, it relied on a static idea of a “continuous historical past…impervious to pollution from foreign sources.” When men and women traveled from the Caribbean in the 1940s and 1950s to England, they expected to be welcomed there “in the same uncomplicated manner…which a child expects from the mother,” he writes. “Sadly, they were soon to discover that the chilliness did not just refer to the weather.” “Race and ethnicity are the bricks and mortar with which the British have traditionally built a wall around the perimeter of their island nation and created fixity.”

In making Rhys just another blinkered Brit, Phillips may be saying more about the literary culture that has welcomed her than her books themselves. It’s in this small act of revenge that he best embodies the spirit of his subject.