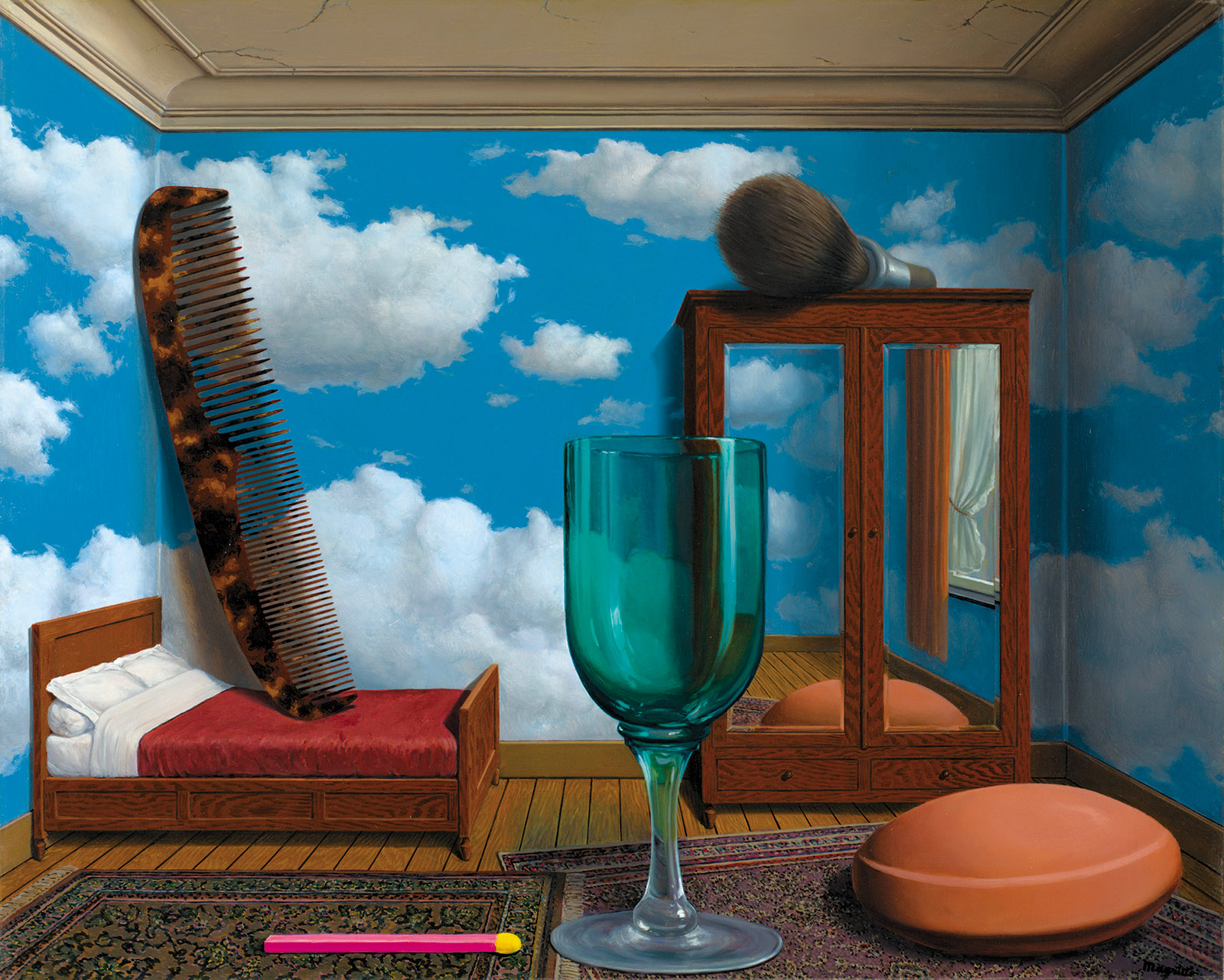

In October 1952, René Magritte’s New York dealer, Alexander Iolas, a champion of the Surrealists in the United States and elsewhere, wrote him in protest. He had recently unpacked Personal Values (1952), the first of what are sometimes called Magritte’s hypertrophic images, in which oversized objects appear to crowd their settings. In this case, a lusciously painted tortoiseshell comb, a vivid blue-green glass, a gargantuan bar of soap, and other personal items dwarf a modest bedroom. The colors made him sick, Iolas reported. Had the work been hastily painted? He begged Magritte for an explanation:

I am so depressed that I cannot yet get used to it. It may be a masterpiece, but every time I look at it I feel ill…. It leaves me helpless, it puzzles me, it makes me feel confused and I don’t know if I like it.

One has to admire this freshness of perception in a man who also represented Max Ernst and was no stranger to disturbing imagery.1 Perhaps Iolas’s honesty disarmed Magritte. “Well, this is proof of the effectiveness of the picture,” he replied. “A picture which is really alive should make the spectator feel ill.”

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art bought Personal Values in 1998, after the death of its most recent owner, Harry Torczyner, Magritte’s lawyer and friend. As the curator Caitlin Haskell explains in the excellent catalog for “René Magritte: The Fifth Season,” in 2013 the painting was loaned to the Musée Magritte in Brussels during SFMoMA’s two-year closure for expansion, but remained on her mind. She and her fellow curator Gary Garrels began to conceive a show “that would focus on the artist’s late work, from the period of our painting forward, and correct the misconception that it was, for better or for worse, a return to his Surrealism of the 1920s and 1930s.”2

But this would mean revisiting—even attempting to rehabilitate—Magritte’s unpopular art from the 1940s: his bright, quirky “sunlit surrealism” and the brutal, Fauve-inspired daubs he submitted in 1948 for his first solo exhibition in Paris. If these two bodies of work were an aberration, they were a sustained one, conducted over five years. Magritte completed over a hundred examples of sunlit Surrealism (a term derived from a postwar Belgian Surrealist manifesto, “Surrealism in Full Sunlight,” which was a rejection, in part, of the Paris Surrealists’ increasing interest in mysticism and the esoteric), and almost forty of what he called his vache paintings for his Paris show.

If Modernist painting broke through to the public with “wild beasts” (the Fauves) at the beginning of the twentieth century, his new works, Magritte implied, were the movement’s domesticated apotheosis: the cow. It was a fighting word. The goopy, droopy clown in Pictorial Content (1947) brandishes a knife in one hand and a gun in the other, and supports a head made of ducks, which appear to be vomiting thick gushes of paint. Brown torrents burst through the arm and seat of the clown’s suit, like a cholera outbreak at a circus.

None of the unpalatable vache paintings sold, and both Magritte’s wife and Alexander Iolas implored him to quit the sunlit style, notable not only for its vigorous, impressionistic brushwork and colors but for its sometimes bizarre imagery, for example in Lyricism (1947), an energetic depiction of a smirking, anthropomorphized pear. Beside the pear-face hangs an ordinary, faceless piece of fruit: a pair of pears. Une paire de poires. Une parodie?

In all his work, Magritte aimed to surprise and to defamiliarize. When one looked at his paintings, he remarked, one asked the question “What does it mean?”3 Viewers of the vache and sunlit works seem more likely to ask, “Is this a joke?” Together, the sunlit and vache paintings present one of the most enduring mysteries—and the greatest curatorial challenge—of a career devoted to intellectual puzzles, visual gags, and what Magritte described as his “systematic search for disturbing poetic effects.”

The eldest of three boys, René was born in 1898 in Lessines, Belgium, to Léopold Magritte, a petit-bourgeois merchant, and his depressive wife, Régina, whom Léopold locked in the bedroom each evening for her own safety. One night she escaped from their home in Châtalet and drowned herself in the River Sambre. Magritte was thirteen. Much has been made of a family legend, now discredited, that he watched while his mother’s body was recovered from the water three weeks later, her damp nightgown clinging to her face—the source, it was said, of the shrouded faces in The Lovers (1928) and other paintings.4 Magritte’s own deadpan description of the suicide seems designed to discourage inquiry: “In 1912, his mother Régina is tired of life. She throws herself into the Sambre.”

Advertisement

We know little about Magritte’s childhood. He wrote engagingly about his art and ideas but shared only a handful of early reminiscences. In a 1938 lecture delivered in Antwerp, “La Ligne de Vie” (Lifeline), he recalled staying with his grandmother and aunt in Soignies, a small provincial town, where he played with a girl in the old cemetery:

We visited the underground vaults, whose heavy iron door we could lift up, and we would come up into the light, where a painter from the capital was painting in a very picturesque avenue in the cemetery with its broken stone pillars strewn over the dead leaves. The art of painting then seemed to me to be vaguely magical, and the painter gifted with superior powers.

His family’s rising fortunes can be surmised from the houses they rented and the second home Magritte’s father built in Châtelet, with its stylish Art Nouveau façade: exactly the kind of frippery at which the young Magritte would turn up his nose. At twelve, he started taking painting lessons with a local schoolmaster. Some early paintings in an Impressionist style survive. Despite Léopold’s mercantile focus, he was proud of his son’s talent (later the middle brother, Raymond, a businessman, would also help support René by buying his paintings) and in 1916 sent him to Brussels to enroll in the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts.

When not indulging his passion for detective fiction—particularly the Fantômas books and films, in which the villain, a master of disguise, vanishes time and again as the inspector closes in on him—Magritte occasionally attended his art classes. More importantly, he met the friends who would coalesce into the Belgian avant-garde, among them the painters Paul Delvaux and Pierre-Louis Flouquet, the architect Victor Bourgeois and his brother Pierre, with whom Magritte shared a studio, and E.L.T. Mesens, then a musician, later an art dealer who would help organize the 1936 Surrealist exhibition in London and run the London Gallery with Roland Penrose.

As World War I (and the German occupation of Belgium) ended, the pent-up energy among these writers and artists released itself in a flood of new journals, exhibitions, galleries, manifestos, and alliances. Finally, they could see the revolutionary art that was surfacing in the rest of Europe during and after the war. Pro- and anti-Dada factions emerged in Brussels. Magritte had once tried writing detective novels under a pseudonym, and now contributed theoretical texts and cryptic poems to his friends’ journals and to his own short-lived Dada prospectus, Œsophage, which he coedited with Mesens and in which he declared, “We refuse under any circumstance to explain precisely what people won’t understand.” No second issue of Œesophage appeared.

Ravenous for new ideas, Magritte cycled through Modernist painting styles. A lecture on De Stijl pulled him briefly toward geometric abstraction. Pierre Bourgeois gave him a catalog of Italian Futurism; “in a veritable frenzy,” as Magritte recalled, he turned out Futurist canvases and wrote to Marinetti for further guidance. He began traveling to Paris in 1920, soaking up Cubism and the remains of Fauvism.

These experiments—and the exhaustion of working what he called “idiotic jobs: posters and drawings for advertising”—prepared him for his pivotal encounter with proto-Surrealism. In 1922 the poet Marcel Lecomte showed Magritte and Mesens a reproduction of Giorgio de Chirico’s The Song of Love (1914), a composition of seemingly unrelated objects—a green ball, a rubber glove, and a plaster cast from the head of the Apollo Belvedere—against a wall in what looks like an arid piazza. A locomotive steams across the horizon. Magritte could “not hold back his tears.” He spoke and wrote about this “exceptional meeting” many times: “It was one of the most moving moments of my life: my eyes saw thought for the first time.”

De Chirico’s importance to the Surrealists would be hard to overstate, but by the time Magritte discovered The Song of Love, de Chirico had cast aside what he called his “metaphysical” paintings and was advocating a return to classical tradition. He had painted The Song of Love near the end of a four-year residence in Paris. Soon after the war broke out, he returned to Italy to volunteer for the army, produce ponderous academic paintings, and thumb his nose at modern art.

Yet his earlier works were waiting at the Paul Guillaume gallery in Paris, ready to slay the Surrealists. A chance sighting of de Chirico’s The Child’s Brain (1914) in the gallery window made Yves Tanguy decide on the spot to become a painter. In the same year, André Breton was enthralled at his first encounter with these paintings. He saluted de Chirico in the first Surrealist Manifesto (1924) and introduced his work to Max Ernst and others, who must have marveled that even the titles of de Chirico’s prewar paintings—The Enigma of the Hour, The Disquieting Muses, The Nostalgia of the Infinite—prefigured the language and obsessions of Surrealism.5

Advertisement

When de Chirico returned to Paris in 1924, Breton hailed him as a hero. But the Surrealists were puzzled—insulted, even—by de Chirico’s overworked neoclassical paintings of the 1920s, which seemed a repudiation of their shared ideals. After one dispiriting studio visit, Breton burst out obscenely against de Chirico, and the break was complete by 1926, the year before Magritte moved to Paris. In his memoir, de Chirico would later deride the Surrealists as “that group of degenerates, hooligans, childish layabouts, onanists and spineless people.”

In 1920, Magritte became engaged to Georgette Berger, a childhood playmate from Charleroi whom he had met again by chance in Brussels. She became his only model. They married in 1922, and Georgette, who had studied art, slid easily into Magritte’s boisterous social circle, which soon included the poet Paul Nougé, the writer and art dealer Camille Goemans, the poet Louis Scutenaire, and later Scutenaire’s wife, the writer Irene Hamoir, who would become the leading female figure in the Belgian avant-garde. Belgian Surrealism—in part a kind of cheeky backbench critique of French Surrealism, particularly its devotion to dreams and the irrational—is often dated from the launch of Nougé’s journal, Correspondance, in November 1924. Belgian Dada, Magritte’s first intellectual home, held out briefly but was soon folded into Belgian Surrealism.

Magritte’s first painting under de Chirico’s influence is The Window (1925), in which geometric forms, including a bold orange pyramid in the foreground, destabilize the image of a neurasthenic hand rising from behind a window beside a hovering bird. The tentative brushwork is immature, but the title and other elements suggest that everything was in place for the stylistic breakthroughs of 1926–1927, the period in which his rounded, realistic forms, his flat brushwork, and his repeating motifs emerge, and he began to marry his ideas with his execution. “When it came it was sudden,” he recalled, explaining his stylistic shift. “When you have an idea you must choose an eagle, a rock and some eggs, and you must paint them in a correct, precise way, but not in a manière, in any special technique.”6 Even in Magritte’s occasional examples of biomorphism and other surreal distortions or dissections, the viewer immediately grasps the objects depicted: “My painting has to resemble the world in order to evoke its mystery.”

The crucial word here is “resemble.” The black-and-white art reproductions Magritte pored over during the war produced the same effect on him, he felt, as the original paintings would, and sparked his enduring interest in theories of representation: “For me, a reproduction is enough! Like in literature, you don’t need to see a writer’s manuscript to be interested in his book!” And if a reproduction is adequate, perhaps a substitution would work as well, he began to think, or a mislabeled object, or a word in place of an object.

For a philosopher who worked in paint, clearly the central element was the idea, not its execution: “For me it’s not a question of painting but of thinking.” This must have been a frequent topic of conversation for him. When the Magritte scholar Sarah Whitfield asked his widow if she could view paintings in person that she had already seen in reproduction, Georgette was surprised and amused. She had clearly adopted his view that the material qualities of his paintings were irrelevant, and that to study his application of paint or the thread count of his canvases was to miss the point to a comical degree. (Katrina Rush’s fascinating catalog essay, “‘The Act of Painting Is Hidden,’” belies this assumption.)

Yet Magritte was not so committed to reproduction that he overlooked the sales value of paintings by his hand. He freely copied his own works (especially under pressure from Alexander Iolas) and painted variants of favorite images throughout the years—at one point producing about sixty small copies for an American collector—though he did not go as far as de Chirico, who backdated his copies of his early metaphysical work, essentially forging himself. Among its other pleasures, “The Fifth Season” brings together seven versions of The Dominion of Light (1948–1962?), Magritte’s evening street scene with the daytime sky above. The charm of his original concept and his technical virtuosity combine to make each variant interesting.

In July 1927, Van Hecke gave Magritte his first one-person exhibition at Galerie Le Centaure in Brussels. The show flopped, but on a handshake agreement with Van Hecke to represent Magritte’s future work, Georgette and René moved to Paris. Although Breton had warily recognized the Belgian avant-garde and tried to enlist its support, Magritte found it difficult to penetrate the Paris Surrealist circle. Perhaps for this reason, his three years there were the most productive of his career. Many of his best-known works emerged in the Paris years—including The Lovers; The False Mirror (1929), later the source of the CBS logo; and The Treachery of Images (1929), aka “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”—while he continued to write literary and theoretical texts, collaborate with friends (especially Paul Nougé, who is often referred to as the Breton of Belgium), and work freelance.

Among Magritte’s Paris writings were dreamlike evocations of romantic encounters and romantic accounts of dreaming. “It is like a victory when I manage to recapture the world of my dreams,” he wrote in “Personal Experience,” published after his death by Marcel Mariën. He had dreamed of a woman on a bicycle and of a man unrolling a piece of blue silk that somehow terrified him. On waking, he realized that he had seen the woman in life the day before, but he resisted probing the source of the blue silk: “I cannot bring myself to take away the magic it still has, nor to rank it with objects that you have only to touch or look at once.”

The twelfth and final issue of La Révolution surrealiste, dated December 15, 1929, records the brief embrace of Magritte and the Paris Surrealists. The journal included a photo montage of the Surrealists—for once, with Magritte—surrounding an image of his, and Magritte’s aphorisms, “Les Mots et les images” (Words and Images), a sort of primer of his semiotic explorations. “No object is so tied to its name that we cannot find another one that suits it better,” he began, beside a sketch of a leaf labeled “Le canon” (“The cannon”). But the night before this issue was published, Breton had picked a fight with René and Georgette and the Magrittes left in anger. The idyll was over. Magritte had joined the distinguished list of those exiled by Breton from Surrealism, among them Tristan Tzara, Antonin Artaud, Louis Aragon, Philippe Soupault, and Yves Tanguy.

Given the financial crisis and other disappointments, the Magrittes chose to return to Brussels. They rented a tenement apartment at 135, rue Esseghem, in the Jette district, where Magritte painted in the dining room. They remained until 1954. The building has now been restored as the Magritte House Museum.

In the lean 1930s, Magritte developed his notion of “affinities” between objects, an expansion of the Surrealist passion for juxtaposing disparate objects.7 Here was a new way, he realized, “to make familiar objects scream aloud.” In his 1938 lecture in Antwerp, he explained the genesis of this new direction:

One night in 1936, I woke up in a room with a bird asleep in a cage. Due to a magnificent delusion I saw not a bird but an egg inside the cage. Here was an amazing new poetic secret, for the shock I felt was caused precisely by an affinity between the two objects, cage and egg, whereas before, this shock had been caused by bringing together two unrelated objects.

From this exploration arose works like Hegel’s Vacation (1958), included in the San Francisco exhibition, in which a water glass appears to balance on top of an open umbrella.

Magritte’s eventual rapprochement with Breton made possible his inclusion in the big Surrealist expositions of the 1930s and the success he found in Great Britain, where his old friend and dealer Mesens had settled. Magritte was the clear favorite at the 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition, and he soon returned to London to paint works for the collector Edward James’s city house and to pursue what seems to be his one extramarital affair, with the performance artist Sheila Legge, now immortalized in Claude Cahun’s photographs as the “Surrealist Phantom,” her head wreathed in roses, her face obscured, promoting the opening day of the London show by promenading in costume from Trafalgar Square to the New Burlington Galleries.

Magritte spent most of the war in occupied Belgium, and in 1943 threw off the shackles of identity—his immediately recognizable, neutral style—by adopting a rainbow palette, less sinister subject matter, and loose brush strokes reminiscent of Van Gogh or Renoir. The Nazis had done a better job of disruption than the Surrealists, he told Breton, provoking a furious public denunciation. Some of the “sunlit” works bring “both charm and pleasure,” as Magritte claimed: “I leave to others the business of causing anxiety and terror and mixing everything up as before.” But many of these paintings, as Abigail Solomon-Godeau notes in her catalog essay, are “deeply, thoroughly weird.”

We cannot know how seriously to take Magritte’s declarations about these works or his “Surrealism in Full Sunlight” manifesto. Was he kidding himself or others? The manifesto is a lucid, convincing argument with present-day resonance, but it does not match the images he produced. “Life is wasted when we make it more terrifying, precisely because it is so easy to do so,” he wrote. “It is an easy task because people who are intellectually lazy are convinced that this miserable terror is ‘the truth’…. Creating enchantment is an effective means of counteracting this depressing, banal habit.”

The vache paintings—perhaps the most expressive in his oeuvre—make sense as intentional outrages: the cannibalistic frenzy in The Famine (1948); in The Cripple (1948), a man with pipes emerging from his mouth, beard, eye, forehead. Ça, ce sont des pipes. The 1948 solo exhibition in Paris, his first, was too little, too late. His friend Louis Scutenaire, who helped him name the works, later confirmed that the two were thumbing their noses at those who had neglected Magritte and, over centuries, ridiculed Belgians as rustics: “The important thing was not to enchant the Parisians, but outrage them.” Magritte dashed the paintings off quickly, with thick, rapid strokes of a well-loaded brush. These must have been the only few weeks of his career in which he needed a dropcloth under his easel.

When he returned to his classic, crisp style, his ideas rushed back. In The World of Images (1950/circa 1961), his familiar “window” device frames an ocean sunset, but the pane has shattered, its colored shards on the floor suggesting it had concealed the view with a perfect illusion. His fortunes gradually rose, which led to a break with some Belgian Marxist friends, who could not believe their old comrade would churn out near copies of his own work to indulge Georgette’s desire for luxuries like a grand piano. The late works frequently recycle imagery, but by refining his vision over multiple treatments, Magritte can often rise to works as consummate and disconcerting as The Son of Man (1964), hardly just another apple painting. “Everything we see hides another thing,” Magritte said of this work. “We always want to see what is hidden by what we see.”

In a postwar letter to the Belgian Communist Party, Magritte argued that painting could support the revolution by providing “intellectual luxury” for the working classes. The pleasures of humor, of mystery, of layers of semblance and concealment still operate in these works, even if specific motifs and some entire paintings have become ubiquitous in pop culture and advertising. They are not dulled by familiarity: viewers move through the “Fifth Season” galleries gasping with delight and recognition. In his day, Dalí was considered the master showman of Surrealist painting, but the Belgian in the bowler has captured the crowd.

-

1

A legendary dealer and collector, Iolas also gave Andy Warhol his first solo exhibition in 1952. Past and present images of Iolas’s now-derelict Greek villa can be seen in William E. Jones’s poignant documentary Fall into Ruin (2017). ↩

-

2

“The Fifth Season” can be seen as a sequel to the larger 2013 MoMA retrospective, “Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926–1938,” taking up the narrative at the trickiest part. The Centre Pompidou’s recent show “The Treachery of Images” (2016–2017), focused on Magritte’s thought. Anyone interested in Magritte will want to read his newly translated Selected Writings, edited by Kathleen Rooney and Eric Plattner (University of Minnesota Press, 2016). ↩

-

3

But Magritte did not want the question answered, the puzzle solved. “It does not mean anything,” he continued, “because mystery means nothing either, it is unknowable.” ↩

-

4

On the dismantling of this useful fiction, see David Sylvester’s Magritte: The Silence of the World (Menil Foundation/H.N. Abrams, 1992). ↩

-

5

De Chirico made the list of artists (including Picasso) whom Breton almost approved: “They are not always Surrealists, in that I discern in each of them a certain number of preconceived ideas to which—very naively!—they hold…. They were instruments too full of pride, and this is why they have not always produced a harmonious sound.” ↩

-

6

It is difficult now, after sixty years of avant-garde figurative realism of various schools, to appreciate how stodgy Magritte’s style could appear in the 1930s beside the work of Dalí, for example, or in relation to Abstract Expressionism. ↩

-

7

Lautréamont’s famous description of beauty as “the chance meeting on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella” electrified Philippe Soupault and Breton. ↩