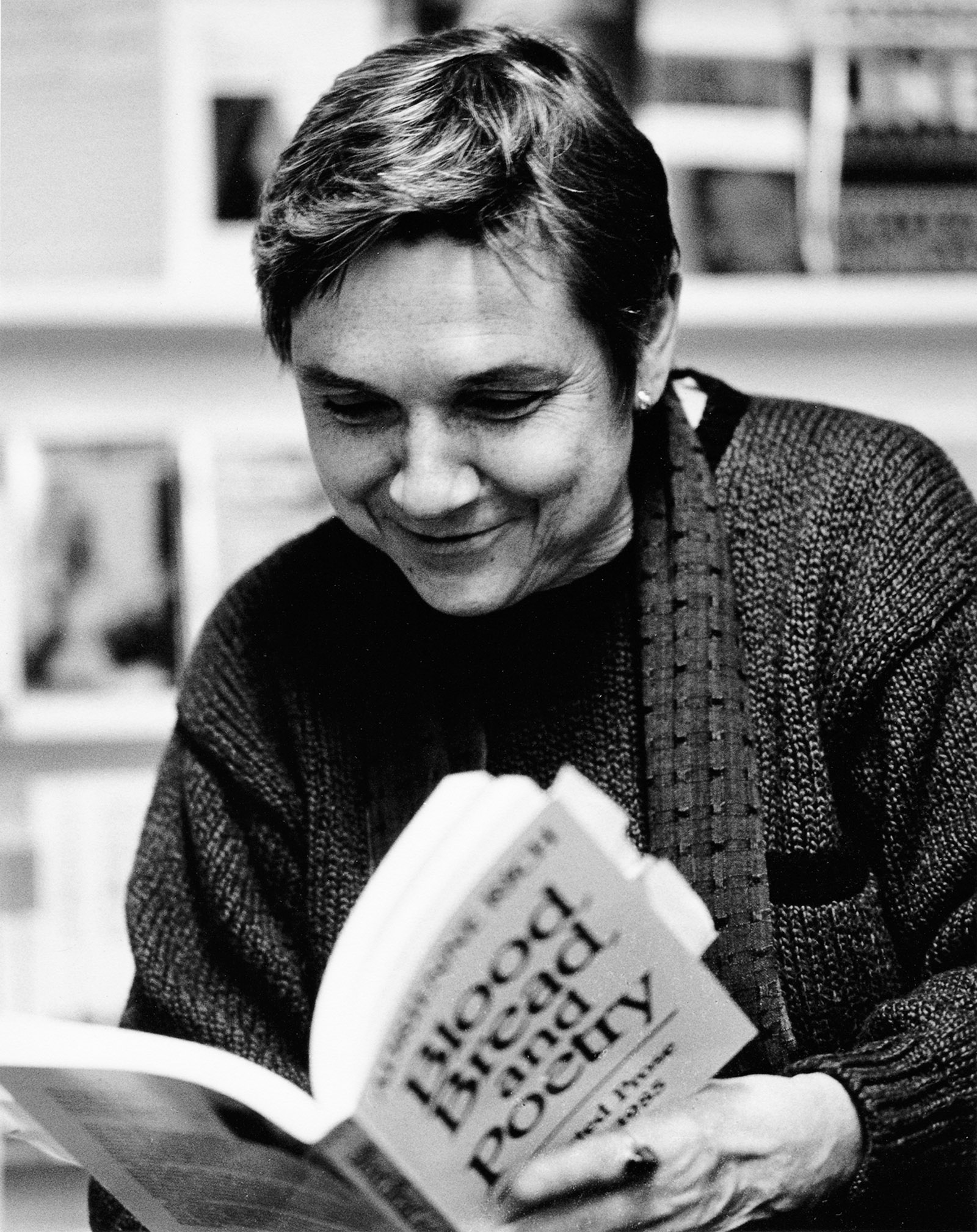

Although Adrienne Rich (1929–2012) never considered herself an epic poet, it’s hard to think of a more apposite definition of her vast and varied oeuvre than the phrase with which Ezra Pound summed up his concept of the modernist epic (speaking, in his case, of The Cantos): “a poem containing history.” Scholars looking to chart the development of America in the six decades spanned by Rich’s career will discover in her work an intermeshing of poetry and history more extensive and searching than that to be found in any of her contemporaries. Her first collection, chosen by W.H. Auden for the Yale Younger Poets Prize of 1951, was presciently titled A Change of World, and the twenty volumes that followed all reveal her astonishing power not only to capture the shifting spirit of the times but to anticipate the dilemmas of the future. Indeed the short eponymous poem of that first volume now reads like an eerie prophecy of our most pressing catastrophe:

Fashions are changing in the sphere.

Oceans are asking wave by wave

What new shapes will be worn next year;

And the mountains, stooped and grave,

Are wondering silently range by range

What if they prove too old for the change.

The trenchant final couplet of this elegantly phrased twelve-line poem goes on to insist, as if in proleptic defiance of all those who still deny the facts of climate change: “They say the season for doubt has passed:/The changes coming are due to last.”

In the light of Rich’s subsequent career, the terms that Auden used to praise her early work in his introduction to A Change of World came to seem almost comically misguided: her poems, he suggests, are “neatly and modestly dressed, speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them, and do not tell fibs.” Yet Auden’s somewhat patronizing précis of the virtues of Rich’s debut volume captures some of the cultural assumptions that initially shaped her, as both a poet and a person, and against which she would in time so spectacularly rebel.

As she herself tells it, in autobiographical poems like “Sources” or “After Dark” and in prose pieces such as “Split at the Root: An Essay on Jewish Identity,” the pressure to conform dominated her upbringing in Baltimore. Her father, Arnold Rich, whose own father was a Jewish immigrant from Austria-Hungary, was a renowned pathologist at Johns Hopkins and committed to the highest ideals of culture. He was also, as Rich tells it, something of a control freak: “He prowled and pounced over my school papers, insisting I use ‘grown-up’ sources; he criticized my poems for faulty technique and gave me books on rhyme and meter and form. His investment in my intellect and talent was egotistical, tyrannical, opinionated, and terribly wearing.” Her mother, Helen, a Protestant from the South, had sacrificed a promising career as a concert pianist to devote herself to her husband’s ambitions and to raise her two daughters, who were brought up as Episcopalians.

It is telling that Auden praised the polished manners of Rich’s early poetry, for it was by rejecting good manners, and exploring all that manners conceal, that she discovered how to move beyond the formal constraints of her first two volumes. “‘Manners,’” she notes in her reflections on her childhood in “Split at the Root,” “included not hurting someone’s feelings by calling her or him a Negro or a Jew—naming the hated identity. This is the mental framework of the 1930s and 1940s in which I was raised.”

In her introduction to the massive Collected Poems of 2016—it runs to over 1,150 pages—Claudia Rankine spoke eloquently of Rich’s “desire for a transformative writing that would invent new ways to be, to see, and to speak.” Rich’s occasional later attacks on the poetry that she had published in the 1950s can be seen as attacks on her own inherited restraint and caution, on her mannerly evasion of poetry’s mission to challenge and transform. The dilemma of the creative woman seeking to express herself in a culture shaped to gratify the needs and desires of men is, nevertheless, brilliantly captured in an early poem such as “Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers”:

Aunt Jennifer’s tigers prance across a screen,

Bright topaz denizens of a world of green.

They do not fear the men beneath the tree;

They pace in sleek chivalric certainty.Aunt Jennifer’s fingers fluttering through her wool

Find even the ivory needle hard to pull.

The massive weight of Uncle’s wedding band

Sits heavily upon Aunt Jennifer’s hand.When Aunt is dead, her terrified hands will lie

Still ringed with ordeals she was mastered by.

The tigers in the panel that she made

Will go on prancing, proud and unafraid.

The poem’s lightly delivered ironies are suffused with a delicate pathos, while its tone of faux naiveté conveys to the knowing reader a deft and sophisticated wit; yet with hindsight it can also be read as anticipating the development of Rich’s own future poetry, which, like these prancing tigers, proud and unafraid, would speak out forcefully against all the assumptions and conventions and institutions that “mastered” Aunt Jennifer.

Advertisement

Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law (1963) is often presented as initiating Rich’s quest to create a poetry beyond the decorous sonorities, the clever conceits, and the Frost-inspired character studies of A Change of World and The Diamond Cutters (1955). The collection’s ten-part title poem also shows Rich in the act of defining a genealogy of inspiring female precursors: Boadicea, Mary Wollstonecraft, Emily Dickinson, and Simone de Beauvoir are all invoked in a series of linked vignettes that culminates in her vision of a messianic female liberator, “delivered/palpable/ours.” On the other side of the ledger, various misogynistic statements by men such as Diderot and Samuel Johnson (“Not that it is done well, but/that it is done at all”) are held up for ridicule.

The poem’s most haunting moments, however, are fraught with a more confused and confessional charge—it was composed between 1958 and 1960 and seems to me to reveal the influence of Robert Lowell’s own watershed sequence, Life Studies (1959). As in Lowell, these moments explicitly dramatize what would become a 1960s slogan: The personal is political. The frustrated daughter-in-law has “let the tapstream scald her arm,/a match burn to her thumbnail,//or held her hand above the kettle’s snout/right in the woolly steam.” Her impulse toward self-harm is figured as an internalization of the culture’s instinctive violence toward women: “A thinking woman sleeps with monsters./The beak that grips her, she becomes.” This poem is Rich’s first deliberate act of resistance against these monsters and the beaks that would grip her; it’s her radical answer to Yeats’s rhetorical question at the end of his sonnet “Leda and the Swan.”

It is not from a man, however, but from the stifled and etiolated mother-figure so movingly dramatized in the opening section of “Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law” that Rich must first liberate herself, while the poem must escape from the cadences and aura of Lowell’s “Skunk Hour.” The parallels between the two poems’ openings are particularly striking, for Rich’s Shreveport belle, her mind now “mouldering like wedding-cake/heavy with useless experience,” is the southern counterpart of Lowell’s self-marooned hermit heiress, an isolated eccentric who buys up all the eyesores on the Maine shore opposite her home on Nautilus Island, only to let them fall. In a later poem, “Re-Forming the Crystal” (1973), Rich tersely observed, “The woman/I needed to call my mother/was silenced before I was born,” and “Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law” also tallies up the salient differences between two generations of women.

It is her diagnosis of maternal “mouldering” that first sets Rich on the path to autonomy: “Nervy, glowering, your daughter/wipes the teaspoons, grows another way.” In her prose study Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (1976), which analyzes in detail the ways in which the patriarchal mind-set warps the mother–daughter relationship, Rich offers a telling gloss on the struggle to escape a mother’s complicity in her own state of powerlessness that is so delicately anatomized in “Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law”:

Many daughters live in rage at their mothers for having accepted, too readily and passively, “whatever comes.” A mother’s victimization does not merely humiliate her, it mutilates the daughter who watches her for clues as to what it means to be a woman.

Like Sylvia Plath—who identified Rich as her main rival, and even resolved to put more philosophy into her own poems so as not to “lag behind ACR”—Rich belonged to a generation of women poets whose creative ambitions and talents by no means exempted them from the expectation that they would also be exemplary 1950s housewives and mothers. She married the left-wing Harvard economist Alfred Conrad in 1953, and by the time she had finished “Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law” in 1960, she was the mother of three sons under the age of six. She benefited, like Plath, from the scholarships available in that era for those identified as gifted high-achievers, traveling to Europe on a Guggenheim in 1952–1953, and then again in 1961–1962.

But most of the period from 1953 to 1966 she lived as a faculty wife and young mother in the leafy purlieus of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the diary entries she includes in Of Woman Born suggest more than a little frustration with all that this entailed. “This is one of the few mornings on which I haven’t felt terrible mental depression and physical exhaustion,” she records of a good day in August 1958, while toward the end of this period, in April 1965, she laments: “Anger, weariness, demoralization…. I weep, and weep, and the sense of powerlessness spreads like a cancer through my being.”

Advertisement

The disapproval of her own parents weighed on her too; Conrad (born Alfred Cohen) came from an observant Jewish family based in Brooklyn, and her choice of husband ran starkly counter to her secular, indeed atheistic father’s narrative of assimilation. “I limped off, torn at the roots,” Rich reflects in a poem of 1964 addressed to her father, who had refused to attend her wedding; “stopped singing a whole year,/got a new body, new breath,/got children, croaked for words.” The image offered here of the singing poet reduced to a frog or toad, able only to croak, suggests a genuine fear. In the event, however, Rich was rarely inarticulate for long; indeed one of the most startling aspects of her career as a whole was her ability to find, seemingly effortlessly, forms and idioms appropriate to each new phase of her development. The sheer eloquence of poem after poem, whatever style or decade they happened to be written in, can take one’s breath away.

Still, like many Rich admirers, I would probably argue that it was during her middle period—from, say, 1966, when she settled with her family in New York, to 1977, when she published The Dream of a Common Language—that Rich’s poetry was at its most gripping and resourceful. From the mid-1960s on she became involved in the civil rights and anti–Vietnam War movements, and her work begins to expound explicit polemical arguments and refer to admired political thinkers or activists. She began teaching in the SEEK (Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge) program at the City University of New York (where Conrad had taken up a post); this was aimed at the economically disadvantaged, and the writers whose work she taught there included James Baldwin (whose essays had a galvanizing effect on her), Frederick Douglass (who, she asserts, “wrote an English purer than Milton’s”), Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon (about whom she wrote a poem published in Leaflets), Langston Hughes, Eldridge Cleaver, W.E.B. Du Bois, and LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), for whom she also wrote a poem.

The confluence of political and personal events charted in the poems collected in Leaflets (1969), The Will to Change (1971), and Diving into the Wreck (1973) enabled Rich to dramatize her experiences during those tumultuous and troubled years with the urgency and clarity of a great autobiography or documentary. At the conclusion of “Planetarium,” composed in 1968, she succinctly defined the pressures shaping her sense of poetry during this period, in relation both to her personal crises and to the upheavals convulsing the nation:

I am an instrument in the shape

of a woman trying to translate pulsations

into images for the relief of the body

and the reconstruction of the mind.

She is in theory here describing the life of the female astronomer Caroline Herschel (1750–1848), but the lines also perfectly capture her own sense of mission; for in these years it became increasingly clear to her that only wholesale “reconstruction” of the values and systems that determined American culture and politics could redeem the nation, and grant its citizens relief.

Her own crisis reached its ghastly apogee in October 1970, when Alfred Conrad, who had for a time been suffering from depression, committed suicide. By this time he and Rich had separated, and in the course of a trip to Vermont that autumn he shot himself fatally in the head. In a poem of 1972, “From a Survivor,” Rich muses on “the leap/we talked, too late, of making,” and attempts to analyze their relationship from a sociohistorical perspective. The failure of their marriage is placed against the background of “the failures of the race”—by which she means her generation of the human race (“The pact that we made was the ordinary pact/of men & women in those days”):

Lucky or unlucky, we didn’t know

the race had failures of that order

and that we were going to share them

But Rich concludes this grieved but battling poem, one of a number of moving elegies for her husband, by articulating her own survivor’s leap into “a succession of brief, amazing movements//each one making possible the next.”

Her husband’s violent and premature death may also be subliminally present in the much-anthologized “Diving into the Wreck,” the title poem of the volume that includes “From a Survivor.” It is, at any rate, a poem about salvaging what can be salvaged from a disaster, and the poet’s agonized descent involves, like “From a Survivor,” both terrible physical pain (Rich herself suffered from her early twenties until her death from debilitating attacks of rheumatoid arthritis) and an influx of energy and purpose: “I am blacking out and yet/my mask is powerful/it pumps my blood with power.” “Diving into the Wreck” is often read as one of the most potent illustrations of second-wave feminism’s ideals and strategies, but it is worth noting that Rich’s genderless narrator figures her/himself as both mermaid and merman (“I am she: I am he”), thus allowing the poem to speak for the disenfranchised in general.

Indeed, what is often striking about Rich’s concept of “transformative writing,” to borrow Claudia Rankine’s formulation, is its Whitmanian inclusiveness, as well as its use of rhetorical strategies derived from one of her earliest enthusiasms, Wallace Stevens. “Not Ideas About the Thing But the Thing Itself” runs a typical Stevens title, and crucial to Rich’s redemptive vision of poetry is the act of clearing away the mythical accretions, the inherited narratives, that prevent analysis and understanding and liberation: “the wreck and not the story of the wreck/the thing itself and not the myth.” The poem, accordingly, foregrounds its awareness of its own myth-making powers (“The words are purposes./The words are maps”), allowing this self-consciousness to balance a narrative that resembles a Spenserian allegory, or Robert Browning’s embittered fantasia of knightly quest, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”: having crawled, “like an insect,” in the modern “body-armor” of a black rubber wetsuit, and in crippling flippers and an absurd mask, rung by rung down to the water, the protagonist sinks through the “deep element” to a reef and then to the wreck itself, where she or he discovers “the damage that was done/and the treasures that prevail.”

These treasures are what is worth preserving from the wreck of Western civilization—whose flotsam includes “half-destroyed instruments,” a “water-eaten log,” and a “fouled compass.” Like Browning, Rich wonders whether it is “cowardice or courage” that has impelled her protagonist to this confrontation with a whole history of deceits and failures, of loss and pain; and while Browning’s knight raises his “slug-horn” to his lips to signify the onset of battle, Rich’s heroic diver brandishes “a knife, a camera,” and “a book of myths,” a book “in which/our names do not appear.”

The 1970s also saw the publication of many of Rich’s most influential and vigorously argued prose polemics. In these she inscribed the names suppressed or elided from the book of myths, and forcefully outlined the processes that aimed to keep them invisible, and hence powerless. Occasional utopian fantasies offer moments of uplift in these texts, but in general Rich trains a beady and unillusioned eye on the outrageousness of the crimes suffered by women, as well as on the enormity of the task confronting the activist seeking change.

“Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” (1980), written some four years after she came out as a lesbian herself, soberly concludes: “It will require a courageous grasp of the politics and economics, as well as the cultural propaganda, of heterosexuality to carry us beyond individual cases or diversified group situations into the complex kind of overview needed to undo the power men everywhere wield over women, power which has become a model for every other form of exploitation and illegitimate control.” That last clause again indicates the wide-angled nature of Rich’s comprehension of the ongoing conflict between the powerful and the dispossessed. The focus of her work as a cultural critic was on the politics of gender and sexuality, but she also insistently looked beyond “individual cases or diversified group situations” to an “overview” that, once grasped, would, she hoped, make change inevitable. Given her opinions, and the passion with which she held and propounded them, it is almost a comfort to reflect that Rich never lived to see Donald Trump in the White House.

It was probably her “Twenty-One Love Poems” of 1974–1976 that most decisively ensured that Rich’s own lesbian love life would not be censored from the record: these poems include explicitly erotic scenes between the “two lovers of one gender”—“your strong tongue and slender fingers/reaching where I had been waiting years for you/in my rose-wet cave”—and it is interesting to contrast her frankness with Elizabeth Bishop’s more cryptic references to her relationships with women. In a 1983 review of Bishop’s Complete Poems included in Essential Essays, Rich ponders the extent to which Bishop’s gift for alienated description—her “eye of the outsider”—and her frequent dramatizations of acute self-division derived from her reticence about her sexual orientation, from the fact that she was a “lesbian writing under the false universal of heterosexuality.” Rich brilliantly interprets “A Cold Spring,” which consists entirely of a description of the coming of spring in Maryland, as a coded lesbian love poem, and in the review’s final paragraph defiantly claims that Bishop, who refused to allow her poems to be included in women-only anthologies, should be read “as part of a female and lesbian tradition rather than simply as one of the few and ‘exceptional’ women admitted to the male canon.”

Rich also recalls giving Bishop a lift from New York to Boston in the early 1970s. “We found ourselves talking,” she remembers, “of the recent suicides in each of our lives” (Bishop’s Brazilian partner of some fifteen years, Lota de Macedo Soares, had killed herself in 1967), “telling ‘how it happened’ as people speak who feel they will be understood.” How must Bishop’s numerous exegetes and biographers have wished that a more detailed account of this conversation had been preserved! It’s possible that Rich made a fuller record of their exchanges, which she found so fascinating that she missed the turnoff at Hartford, but the majority of her letters are embargoed until 2050, in the hope of discouraging any “publishing scoundrel,” to use Henry James’s phrase, from writing her life in the near future. In the same spirit, Rich requested, shortly before she died, that family and friends refrain from collaborating with any prospective biographers.

Rich’s poetry has not yet spawned a secondary literature as extensive as that generated by Bishop’s, in part, perhaps, because it lacks the reticence and mystery implicit in the work of “a creature divided” (to quote from Bishop’s final poem, “Sonnet”): as she aged, and improved, Bishop brilliantly discovered new ways of deploying the formal resources of the lyric to depict landscapes or to recreate encounters—such as that with the moose—that half-conceal and half-reveal her inner motivations, whereas Rich’s development involved experimenting with more open, Whitman-inspired forms, and more emphatic kinds of language, in order to present “an atlas of the difficult world,” to borrow the title of a collection from the early 1990s. Indeed, much of Rich’s poetry from the mid-1960s onward communicates an intoxicating sense of freedom and possibility—can be thought of as “flying,” to quote again from Bishop’s final poem, “wherever/it feels like, gay!” In much of this post-1960s work, even when Rich presents herself as embattled or enraged or consumed by doubt, which she often does, the reader rarely loses faith in the poetry’s ability to articulate and negotiate the problems and issues that it charts. “Despair falls,” a poem may begin (“Dreams Before Waking”), but it ends by discovering a reverse perspective on the grimness of its opening mood:

Though your life felt arduous

new and unmapped and strange

what would it mean to stand on the first

page of the end of despair?

It is the resilience and ebullience of Rich’s poetry that lingers in the mind, as much as her scathing diagnoses of the ills besetting the West. And her own final poem, “Endpapers” (2011), concludes with an image that at once summons up and encapsulates the ongoing relationship with her readers that makes the whole experience of engaging with Rich’s imagination such a communal and affirming process:

trust in the witnesses

a vial of invisible ink

a sheet of paper held steady

after the end-stroke

above a deciphering flame

This flame might burn, but it doesn’t; rather, even after her “end-stroke,” it allows us to decipher the words written in invisible ink, and then to apply them to the world as it changes around us.

This Issue

November 8, 2018

MLK: What We Lost

The Concrete Jungle