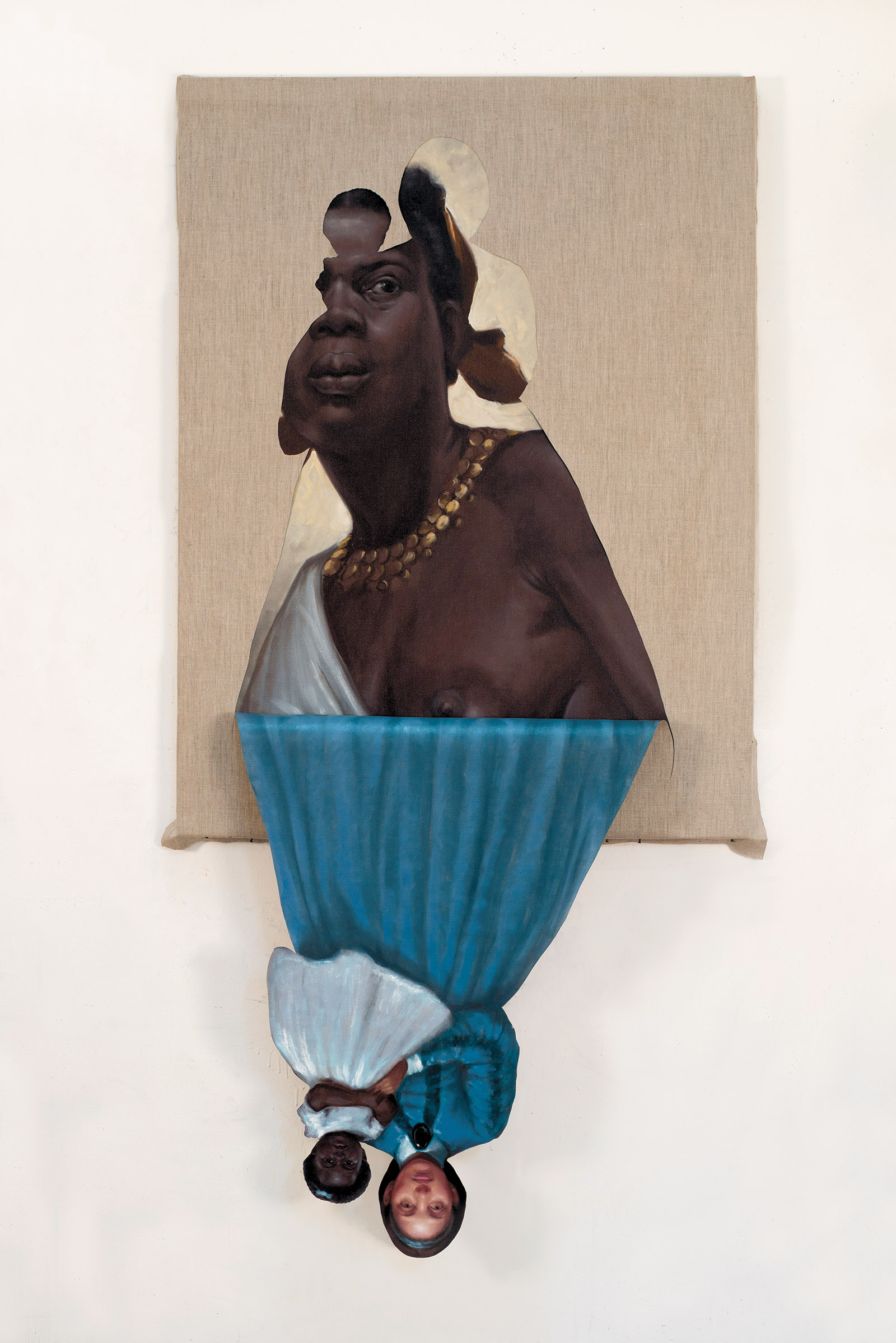

Titus Kaphar/Private Collection/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Titus Kaphar: Her Mother’s Mother’s Mother, 2014; from the exhibition ‘UnSeen: Our Past in a New Light,’ which includes work by Kaphar and Ken Gonzales-Day.It is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C., through January 6, 2019.

Jill Lepore has achieved singular prominence as an American historian. The David Woods Kemper ’41 Professor of American History at Harvard, she has written eleven books over the last twenty years, among them a Bancroft Prize winner and finalists for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Since 2005, she has regularly contributed essays and reviews to The New Yorker, where she is a staff writer. More successfully than any other American historian of her generation, she has gained a wide general readership without compromising her academic standing.

Lepore’s work for The New Yorker has allowed her to develop an engaging narrative style that relies heavily on exact detail and clever metaphors. Her talents as a storyteller have been best suited to a small canvas, to the uncovering of hitherto obscure and marginal lives and the interpretation of particular episodes and arresting characters, especially if they stand at a remove from the main figures and events of American history—not the Revolution, for example, but a rumored slave uprising in New York almost three decades earlier; not Benjamin Franklin but his utterly forgotten and much distressed sister Jane; not any consequential modern bohemian writer but the Greenwich Village exhibitionist and sponger Joe Gould, who just may have actually written (or so Lepore hints) his notorious, monumental “Oral History of Our Time.”1 If, finally, much remains either insignificant or unknowable, she leaves her readers impressed with her powers of detection and her empathic imagination.

Lepore has now written her most ambitious book to date: These Truths, a one-volume national political history of the US. In 2010, shocked at the rising Tea Party movement’s grotesque abuse of the history of the American Revolution, she contributed an elegant corrective, The Whites of Their Eyes. The book presented the historian’s craft as essential to exposing facile, plausible, but finally false analogies between the past and the present.

Yet the book also alleged that professional historians had failed in recent decades to offer the general public “sweeping interpretations both of the past and of [their] own time,” an abdication that made them complicit in the flagrant debasement of the past in contemporary politics.2 These Truths may well have started out as an effort to help fill that supposed void. But if so, while she was writing the book, the ascendancy of Donald Trump turned the void into something resembling a cyclone.

Lepore begins not with a grand explanatory theory of American history but with a question, around which she develops various themes. She posits that the nation was built on three principles or truths: political equality, natural rights, and popular sovereignty. Armed with those concepts, the Revolutionary generation wagered that humanity could, as Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 1, establish “good government from reflection and choice,” instead of being “forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.” For Lepore, relating the nation’s history comes down to a test: Has the wager succeeded? In arriving at a verdict, she tells a story of torment and betrayal offset by decency and innovation, of a nation that has repeatedly departed from its founding truths but always, even in the worst of times, returned to them.

Well before the nation’s founding, slavery called into question the consistency and even the sincerity of the Revolutionaries’ principles, and Lepore places it at the center of These Truths from the very first pages. Her unconventional take on the most difficult subject in our history is her book’s most important contribution. One well-established line of argument holds that the Revolution unleashed what Bernard Bailyn once called a “contagion of liberty” that eventually challenged the enormity of slavery. Another line is tougher on the Revolution’s hypocrisy, echoing Samuel Johnson’s famous jibe about hearing “the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes.” A still-darker argument asserts that slavery was a cornerstone of the Revolution’s republicanism—that slaveholding aristocratic rebels like Washington, Jefferson, and Madison could, as Edmund Morgan wrote, “more safely preach equality in a slave society than in a free one,” and that they accordingly promoted a racist republicanism that kept poorer whites contented by the fact that they were not black and not enslaved.

Lepore, however, advances an emerging view among historians that there were two eighteenth-century revolutions in America, not one: the familiar successful rebellion against monarchical rule and a less remembered one to abolish slavery that would not succeed until 1865. In Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin observed that “the establishment of democracy…was scarcely as radical a break with the past as was the necessity, which Americans faced, of broadening this concept to include black men.” Lepore would agree that the eradication of slavery—an institution that dated back to antiquity in Western culture—and the extension of equality to the formerly enslaved and their descendants, an extension still starkly incomplete, has been as profound a revolution as any in modern history.

Advertisement

The roots of the American antislavery revolution, in the revisionist telling, are in the rebellions and political struggles of slaves and free blacks. Supported by some prominent whites, including John Jay and Gouverneur Morris, the antislavery struggle became entwined with the truths of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution; slaveholders and their supporters, meanwhile, cited those same truths in defense of their supposed natural right to own human beings as property. From the nation’s founding until the Civil War, American politics came to turn on which version of the Revolution’s principles would prevail. It was a struggle that would only be settled in blood.

This line of argument helps make sense of how a new nation designed in part to protect slavery could also generate a mass political movement that pushed for slavery’s containment and ultimate extinction.3 Lepore successfully links the story of slavery and antislavery with that of the widening of democracy for white men through the 1830s and 1840s, aware of how the expansion of popular politics at once hindered and advanced the rising antislavery cause. She skillfully weaves individual experiences into the vagaries of social and political change, memorably the life of George Washington’s slave Harry Washington, who escaped Mount Vernon in 1776, fought with the British army, arrived with other Loyalists after the Revolution in Nova Scotia, and ended up in Sierra Leone, where he helped lead an unsuccessful revolution of blacks against the colonial British authorities. Lepore also remains a demon for detail, right down to describing the gold-embroidered cuffs and wing-like epaulets of a Mexican ambassador who survived a fateful shipboard explosion on the Potomac that nearly killed President John Tyler in 1844.

Like any ambitious book covering several centuries, These Truths contains trivial slips that can be easily corrected in the next printing: the occasional misspelling of a name or the misdating of a significant event. But especially in light of the book’s themes and Lepore’s precision elsewhere, it’s perplexing to read, for example, the ambiguous statement that the Constitution’s three-fifths clause, by substantially enlarging slaveholding states’ allotment in the House of Representatives, granted those states “far greater representation in Congress than free states,” an assertion that, if taken to mean proportions in the House, would be inaccurate.4 The framers did not resolve their larger impasse over representation in the House and Senate by passing the Northwest Ordinance—Lepore seems unaware that the Confederation Congress, and not the Constitutional Convention, approved the measure—nor did the ordinance decree that states south of the Ohio River would continue slavery. If any of these assertions were accurate, the politics of slavery and antislavery over the following decades would have been markedly different, so the fumbles are not inconsequential.

Some shakiness about elementary facts, especially on politics, recurs in later chapters. Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans did not, as the book asserts, align as, respectively, antislavery and proslavery parties prior to the momentous crisis over the admission of Missouri as a slave state in 1819 and 1820; most congressmen in what John Quincy Adams called the “free party” were in fact northern Republicans. Adams, who was by then a Republican himself, did become increasingly opposed to slavery over the following decades, as Lepore relates, but partly on that account, he never “steered the erratic course of the Whig Party,” as the book contends. If he had, something like Lincoln’s Republican Party might have arisen two decades earlier than it did.

Together, these lapses make the founding generation appear more proslavery and the later Federalist and Whig parties more antislavery than they actually were, but they can be adjusted without weakening Lepore’s general argument. Her handling of the Jacksonian Democrats is a little more troubling. Although she is more evenhanded than many historians—she avoids making the mistake others on the left have made recently of echoing the Trump administration’s spurious claims to Jackson’s legacy—she does label the Jacksonians’ democratic conception of popular sovereignty a species of “populism,” thereby making Jackson the chief forerunner of what the book will go on to describe as a thoroughly rancid strain in American political history. This loose conception of populism, as Manisha Sinha has observed, tendentiously conflates “anti-democratic forces of the twentieth century” with Jackson’s white man’s democracy and later nineteenth-century democratic movements.5 Here it signals Lepore’s interest in showing how some of Trumpism’s origins emerged long before Trump’s presidency, a course she pursues with uneven success.

Advertisement

These Truths divides the nation’s history after the Civil War into two parts, breaking at 1945, and offers two contrasting arcs. After the overthrow of Reconstruction and with the coming of the Gilded Age, the principles of equality, natural rights, and popular rule rapidly receded, supplanted by a new industrial plutocracy and accompanied by vicious white supremacy. Progressive reformers for a time curbed the excesses, but the old order persisted until it collapsed in the Great Depression, clearing the way for FDR’s New Deal, followed by America’s emergence after World War II as the indispensable nation in the creation of a new liberal-democratic world order.

Thereafter plutocracy abated, as liberalism finally addressed the most egregious systems of racial oppression and persistent economic inequality—only to see a fierce conservative reaction led by Ronald Reagan swamp a shaken and feckless Democratic opposition and usher in a second Gilded Age, with Republicans and Democrats alike poisoning politics. “The nation had lost its way in the politics of mutually assured epistemological destruction,” Lepore asserts. “There was no truth, only innuendo, rumor, and bias. There was no reasonable explanation; there was only conspiracy”—that is her description of the 1990s. If Trumpism’s advent in 2016 was not inevitable, the political crack-up that produced it began decades earlier, until the system, under Bill Clinton, began falling into what Lepore calls an “abyss.” Lepore’s interpretation focuses on the intersection of culture and politics, but overall, while persuasive on culture, it is much less so on politics.

Although politics remains at the core of her book, Lepore is most at home discussing cultural artifacts and trends, analyzing, for example, the 1957 Katharine Hepburn–Spencer Tracy film Desk Set as a kind of manifesto “about mass democracy and the chaos of facts.” Insofar as radio, the movies, television, and the Internet have fundamentally changed politics—with even greater volatility than the mass-circulation press in the 1830s and after—media deservedly loom large, as does the history of regulation. And insofar as movement conservatism after the 1960s triumphed as a result of the instigation and manipulation of various culture wars (which Lepore smartly ties to the career of the hard-right polemicist and organizer Phyllis Schlafly), the entwining of culture and politics lies at the heart of recent history. For Lepore, the rise of populist politics and the invention of instruments of mass deception are particularly notable—and with her invocations of populist intolerance, as well as of the early history of “fake news” (a term, she shows, that dates back to the 1930s but rings more authentically in the original German), it’s not difficult to see where her book is heading.

“Populism,” Lepore writes, “entered American politics at the end of the nineteenth century, and it never left.” Her account of the rise of the People’s Party (also known as the Populists) in 1891 is sometimes heavily slanted toward the odious or just bewildering. According to Lepore, the Populists’ response to economic injustice combined a conspiracy-minded hatred of the rich with a vicious racism and nativism, including anti-Semitism, that “rank among its longest-lasting legacies.” And while it pitted whites against nonwhites, she writes, “populism also pitted the people against the state.” By these lights, what she calls populism’s enduring political legacy resides mainly in today’s Republican Party.

Lepore’s account revives the hostile interpretation of the Populists advanced by Edward Shils and Peter Viereck, and in a far more nuanced way by Richard Hofstadter, in the 1950s. That view, however, has long since been refuted by the research of several historians who demonstrated that the Populists were no less tolerant of immigrants and blacks, and in some respects more so, than mainstream politicians and the well-born shapers of respectable opinion were.6 The Populists’ chief demands—for state regulation and even ownership of railroads and telegraph companies, for inflationary monetary policies, and for a graduated income tax—were hardly outbursts of either anticapitalist paranoia or nativism and white supremacy. It is impossible, moreover, to square these proposals, which Lepore at one point calls “collectivist,” with her contention that the Populists’ reformation entailed opposing the state.

Twentieth- and twenty-first-century eruptions that Lepore describes as populist—including the anti–New Deal fulminations of the anti-Semitic demagogue priest Charles Coughlin, the Tea Party, the alt-right, and, in a left-wing antigovernment variant, Occupy Wall Street—have had nothing to do with the populist tradition, which persisted during the 1920s and 1930s in political organizations like the leftist Nonpartisan League and the Farmer-Labor Party movement. Above all, there is nothing of the populist legacy in the calculated fake populism of the modern GOP, which represents a genuine attack on the regulatory state that dates from the big business reactionaries of the 1930s, makes liberals, not plutocrats, into the oppressive elite, and relies heavily on flagrant appeals to white resentment.

Lepore gets back on track when she shifts to the history of the mass media and political polling, and their undermining of deliberative democracy. As early as the 1930s, tools of mass persuasion were bearing out Walter Lippmann’s earlier warnings about the electoral system’s vulnerability to the purposeful obfuscation of reason and facts. Drawing on research she published in The New Yorker during the 2012 presidential campaign, Lepore focuses on the pioneering pro-business consulting firm Campaigns, Inc., known by its critics as the Lie Factory, which started out by slandering Upton Sinclair during his radical gubernatorial race in California in 1934 and went on to launch even more ambitious propaganda efforts for business interests, including the American Medical Association’s scare campaign that defeated President Harry Truman’s attempt to pass national health insurance at the end of the 1940s.

By the 1990s, both national political parties as well as advocacy groups across the ideological spectrum were the captives of a class of cynical political consultants who pocketed enormous sums—the price of doing business in a corporatized democracy. The techniques of manipulation and misinformation had become vastly more sophisticated, especially after the spread of television. But the awful possibilities of mass media, Lepore observes, had been glimpsed long before, when Orson Welles’s Mercury Theatre broadcast over the CBS radio network its notorious, terrifying dramatization of The War of the Worlds in 1938. Across the country, she writes, commentators asked whether “the masses [had] grown too passive, too eager to receive ready-made opinions.” These were, Welles later noted, exactly the questions that the program had intended to provoke. But far worse would come, battering Alexander Hamilton’s original hopes for an American republic governed by reason and choice instead of accident and force.

Lepore’s account of the last quarter-century of American politics inevitably describes the ravages of polarization. One forceful interpretation of that history has emphasized how, in the post-Reagan era, beginning with the ascent of Newt Gingrich and later abetted by Fox News, the Republican Party deliberately coarsened political debate while moving so far to the right that it became no party at all but, as the political scientists Thomas E. Mann and Norman J. Ornstein wrote in 2012, an extreme “insurgent outlier…scornful of compromise; unmoved by conventional understanding of facts, evidence and science; and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition.”7

Lepore recounts these trends but also energetically berates the Democratic Party, which in the 1980s and after, she claims, repudiated New Deal liberalism, substituted the politics of identity for the politics of equality, and embraced a technocratic elitism that “jettisoned people without the means or interest in owning their own computer,” above all blue-collar union members. In blaming both sides she leaves unexplained why, for example, the share of union households voting for Democratic presidential nominees, after suddenly crashing in 1980, rose steadily over the next fifteen years, reaching a peak of 60 percent in 1992, roughly what it had been before Reagan.

Lepore can barely contain her contempt for Bill Clinton, whom she describes as a compromiser who “liked and needed to be liked” by almost everyone, and who was consistent chiefly as a philandering “rascal.” Even before the disastrous midterms of 1994, she says, Clinton had steered his administration to the right; thereafter, he found common ground with Gingrich—she bypasses events like the government shutdowns in which Clinton outwitted Gingrich—and pursued an agenda much of which “amounted to a continuation of work begun by Reagan and [George H.W.] Bush.” On the Lewinsky scandal, Lepore cites Anthony Lewis, who remarked that the country had come “close to a coup d’état,” but leaves mysterious how the plot was hatched or why, given her description of Clinton’s Reaganesque politics, Republicans would have bothered with it. She dangles Andrew Sullivan’s excoriation of Clinton as a cynical, narcissistic, mendacious “cancer on the culture”—overlooking Sullivan’s promotion at The New Republic of a mendacious but influential right-wing attack on Clinton’s health care plan and of the racist blockbuster The Bell Curve—before shifting her rebuke to berate “the conservative media establishment” and Clinton defenders like Gloria Steinem and Toni Morrison, whose blasts of Kenneth Starr and the GOP extremists in Congress she claims “diminished liberalism” by portraying the president as a victim.

An immense and, for Lepore, immensely destructive cultural force also emerged in the 1990s: the Internet. She reasonably blames that emergence in part on what future historians will, I suspect, regard as a truly calamitous piece of Clinton-backed legislation, the Telecommunications Act of 1996. While scrapping what regulation of the telecommunications industry the courts had not already undone, the law opened the way to the consolidation of existing media empires, the creation of vast new monopolies like Google, and the prohibition of government oversight of the Internet and its darker regions, “with,” as Lepore writes, “catastrophic consequences.”

Although the Republicans’ single-minded assaults on progressive taxation were chiefly to blame, the Internet revolution accelerated a worsening of income inequality, which before the economic collapse of 2008–2009 returned to pre–New Deal levels. It also advanced, Lepore asserts, the ruin of both national parties, turning them into hollow shells, “hard and partisan on the outside, empty on the inside,” as well as the debasement of political debate, now unmoored from fact and “newly waged almost entirely online…frantic, desperate, and paranoid.” Even the exceptional (to Lepore) Barack Obama, who she says summoned Americans “to choose our better history,” failed to reverse the chaos, as his “commitment to calm, reasoned deliberation proved untenable in a madcap capital.” Instead there was Trump, buoyed by a new American populism, promoted by utterly unrestrained dynamos of mass deception, and inspired by the very worst in our history.

Lepore does not offer a final verdict on America and its truths, but her concluding lines are anguished, depicting a ship of state being torched by those newly in charge and the craven opposition huddled clueless below decks, with a new generation of Americans called upon “to forge an anchor in the glowing fire of their ideals,” yet in need of “an ancient and nearly forgotten art: how to navigate by the stars.” Another approach, though, would involve returning to Hamilton, who in Federalist 68 explained how the Constitution aimed to obstruct “cabal, intrigue, and corruption” and to defeat the “most deadly adversaries of republican government,” who would seek to exploit “the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils.” Trump may perhaps reflect the worst in the long history that Lepore relates, but in more ways than she suggests, he also represents a sharp break, matched in our history only by Southern secession and the Civil War. Reclaiming America’s truths means, first and foremost, understanding the exact historic dimensions of the unprecedented crisis—a crisis that, beyond demagogy, lies, and phony populism, goes to the legitimacy of the constitutional order.

This Issue

November 8, 2018

MLK: What We Lost

The Concrete Jungle

‘Inventing New Ways to Be’

-

1

In writing on Gould, Lepore succeeded her legendary predecessor at The New Yorker, Joseph Mitchell, noted for his profiles of Gould from 1942 and 1964 that were later collected as Joe Gould’s Secret (Viking, 1965). ↩

-

2

The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle Over American History (Princeton University Press, 2010). An outstanding exception, the radical historian Howard Zinn’s enormously successful A People’s History of the United States, first published in 1980, offers a simplistic narrative that has made it, Lepore once archly observed, the equivalent of The Catcher in the Rye for the budding high school historian—subversive, inspiring, but soon enough a book to outgrow. See “Zinn’s History,” Page-Turner (blog), The New Yorker, February 3, 2010. Lepore’s complaint, however, ignores other, far stronger works such as Eric Foner’s The Story of American Freedom (Norton, 1998). ↩

-

3

See James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (Norton, 2014). ↩

-

4

Even with the three-fifths clause, the Federal Convention allotted thirty-five seats in the House of Representatives to the northern states that had abolished or were in the process of abolishing slavery and thirty seats to the slaveholding states. Contrary to the expectations of many, the free-state majority increased dramatically over the coming decades, meaning that slaveholders always needed the support of sympathetic northerners, a crucial factor in national politics. ↩

-

5

Manisha Sinha, “Making Andrew Jackson Great Again?,” History News Network, January 7, 2018. See also Daniel Howe, “The Nineteenth-Century Trump,” NYR Daily, June 27, 2017; and Andrew Burstein and Nancy Isenberg, “The Democratic Autocrat,” Democracy, Fall 2017. ↩

-

6

See especially Walter Nugent, The Tolerant Populists: Kansas Populism and Nativism (1963; University of Chicago Press, 2013); and Charles Postel, The Populist Vision (Oxford University Press, 2007). ↩

-

7

Thomas E. Mann and Norman J. Ornstein, “Let’s Just Say It: The Republicans Are the Problem,” The Washington Post, April 27, 2012. ↩