Patrick Modiano’s first novel, La Place de l’Étoile, published fifty years ago, is a satire of French anti-Semitism as hilarious as it is unsettling. Modiano, who was twenty-two years old at the time, seems not to have known—or, in some moods, to have cared—whether his book was a parody of racism or a sophisticated example of it. The narrator is Raphäel Schlemilovitch, a French Jew turned Nazi collaborator, who boasts to one of his girlfriends—a Polish Holocaust survivor, no less—that he is “the only Jew ever to be awarded the Iron Cross by Hitler himself.” Schlemilovitch’s adventures include stints as a white slave-trader in the Savoie, the lover of Eva Braun, a torture victim of the Israeli police, and finally a patient of Sigmund Freud, who gives him a copy of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew and assures him that Jews do not really exist.

The humor of La Place de l’Étoile combines high-class literary references with defiantly low-class humor (not unlike the fiction of Michel Houellebecq). On the opening page, Schlemilovitch quotes from an attack on him in the right-wing press. The ellipses are a parody of the notorious anti-Semite Céline’s trademark punctuation, but one also senses, somewhat uneasily, Modiano’s glee in inventing insults:

Schlemilovitch?…Ah, the foul-smelling mould of the ghettos!…that shithouse lothario!…runt of a foreskin!…Lebano-ganaque scumbag!…his Sea of Galilee yachts!…his Sinai neckties!…may his Aryan slave girls rip off his prick!…with their perfect French teeth…their delicate little hands…gorge out his eyes!…death to the Caliph!…

The real target of Modiano’s satire was the Gaullist myth of a heroic France—la France résistante—that had risen against the German Occupation instinctively and in unison. Modiano’s novel reminded readers that the Republic could not be so easily exculpated: anti-Semitism was no aberration but a deeply French tradition, of which writers like Céline were the natural if slightly rotten fruit. La vraie France, as de Gaulle called it, had often defined itself by excluding or vilifying Jews. In this sense, those who collaborated with the Nazis during the war were not traitors but—as many collaborators would also have argued—ordinary French patriots.

Modiano’s skepticism toward the Gaullist consensus was of course shared by many of his contemporaries. The carnivalesque energies of his novel, published in April 1968, seem to presage the protests that erupted a month later. But Modiano’s politics have never been easy to define. He felt little solidarity with the student soixante-huitards, whom he suspected of being the coddled scions of a venal bourgeoisie. Modiano’s own parents were not quite respectable. His father was a Jewish black marketer who was twice rounded up and nearly deported by the Vichy government; his mother, originally from Antwerp, wrote subtitles for a Nazi-financed film company. Although Modiano has written harshly of both parents—particularly in his bracingly bleak memoir, Pedigree—they bequeathed to him a sympathy for outcasts and nonconformists of all kinds.

It was the French right that embraced La Place de l’Étoile most enthusiastically. In May 1968, at the height of the demonstrations, Modiano won the Prix Roger-Nimier—named for the self-styled royalist, author of The Blue Hussar, and outspoken supporter of Céline. The prize was presented by Paul Morand, ex-ambassador of Vichy and soon-to-be member of the Académie Française. Modiano called the award “a misunderstanding,” but he didn’t refuse it.

None of Modiano’s subsequent writings—which include twenty-odd novels, a pair of memoirs, playscripts and screenplays, children’s books and lyrics for Françoise Hardy—has the unruly force of his first fiction (it is hard to imagine anyone writing for long at such a hysterical pitch). The later works tend to be meditative rather than self-dramatizing, elegiac rather than comic, and with realist settings rather than the cartoonish décor of La Place de l’Étoile. But Modiano’s first novel is a remarkable foreshadowing of his determination to think through modern French history—especially though not exclusively the history of the Occupation—on his own terms. If none of his later works is quite as outrageous as the first, they are equally audacious in their own fashion.

It is a commonplace to say that after his early fiction, Modiano keeps writing the same book over and over again, and there is something to this idea. You don’t open a new Modiano novel with the sense that just anything could happen. But it would be more accurate to say that he keeps writing the same genre of novel, a genre the French call un Modiano, in the same way one refers to a noir or a romance. This means that if you enjoy one Modiano, you are likely to enjoy the others as well (which is not to say that they are all equally good), and if you do not like the first one, then chances are you will not like the next, either.

Advertisement

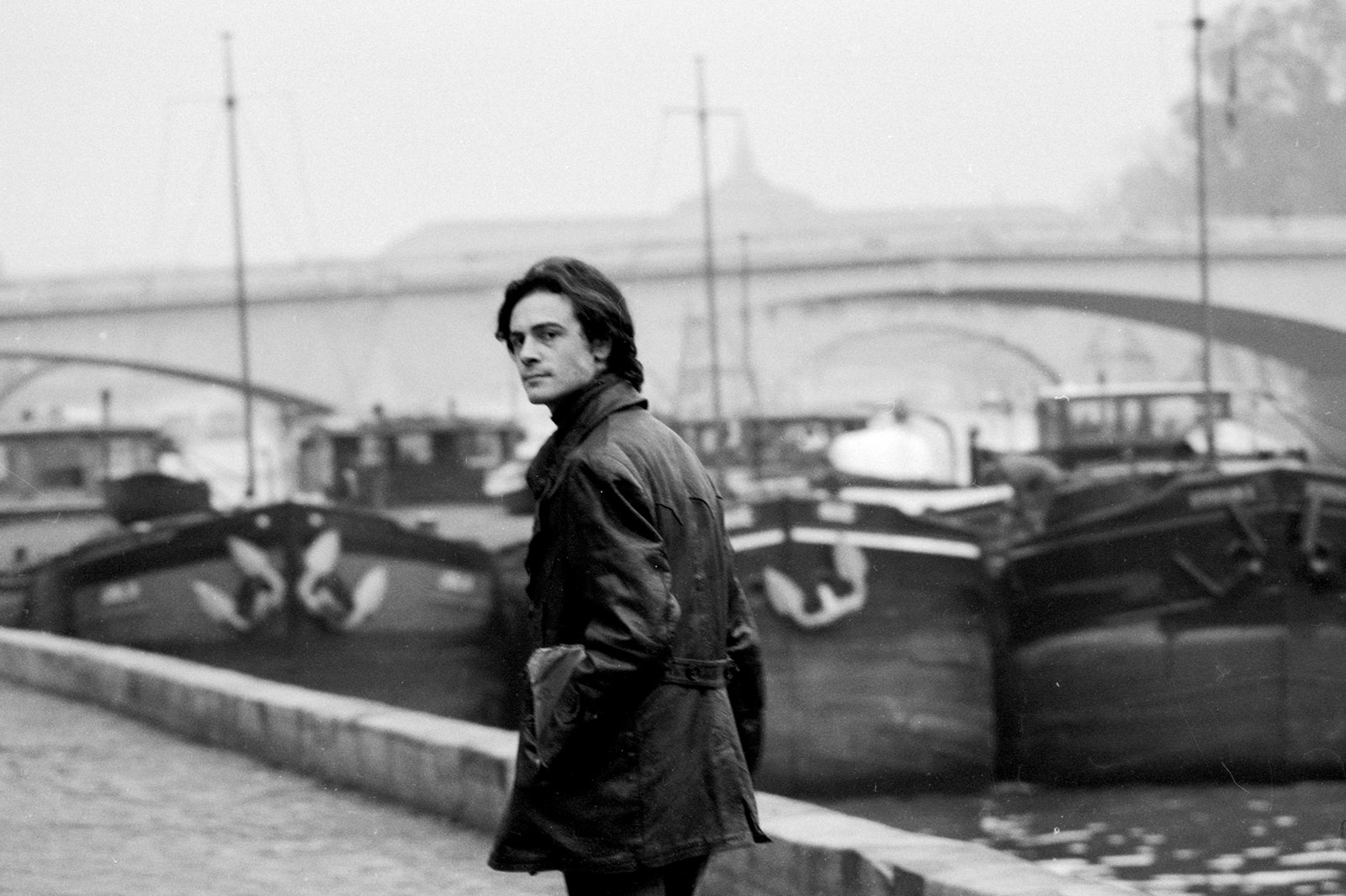

What constitutes the genre? Modiano’s novels are obsessively concerned with the problem of personal identity and its relation to memory; they are often set in out-of-the-way arrondissements of central Paris (neither the banlieus nor the tourist neighborhoods); they share a mood of tense reverie; their plots are fastened around scraps of text, private photos, or personal archives; and the typical characters are drifters, detectives, negligent parents, orphans, and shady businessmen. Many of the protagonists are in flight from their past or seeking in some way to reclaim it, and that past often turns out to have something to do with the war years.

The quintessential Modiano, which manages to combine all these elements into an ingenious and satisfying whole, is Missing Person, winner of the 1978 Prix Goncourt. (If you are looking for a place to start with Modiano, this might be it.) The narrator is an amnesiac private eye who spends the novel searching for clues to his own identity. These clues take the form of phone book listings, scrapbook photos, and old newspaper articles, all of which lead him back to a circle of profiteers operating in wartime Paris. Missing Person has the pace and economy of a good crime novel, but it also has an allegorical heft, suggesting that modern France’s own identity lies somewhere in the fog of occupation.

Sundays in August, first published in 1986 and now available in Damion Searls’s skillful English translation, is a lesser work, but with charms of its own. One pleasure of reading genre fiction is to see how the author recombines or removes stock elements to make something new. Like many of Modiano’s characters, the central couple of Sundays in August, Jean and Sylvia, are fleeing their past. Sylvia has stolen a large diamond from her former lover, a thuggish gem-runner named Frédéric Villecourt, and the couple eventually go to ground in Nice (an unusual setting for Modiano). “I thought that my life was taking a new course,” Jean reflects early in the novel. “I told myself that we would forget everything, that everything would start over in this unknown city.”

Needless to say, that is not how things work out. Modiano uses the fabled light of the Riviera the way Raymond Carver uses California sunshine: its harshness accentuates the shadows. To highlight the noirish elements of his story, Modiano makes Jean a photographer who meets Sylvia while working on a book about the beaches of the Marne—the riverside region southeast of Paris, once the haunt of painters like Cézanne and Pissarro, later a hangout of French movie stars, and now a somewhat seedy suburb. Jean models his work on W. Vennemann’s Monte Carlo: Visions Photographiques, a 1930s photo book that depicts the casino town in glamorous chiaroscuro. As Jean explains his improbable project:

Instead of the shadows of palm trees outlined against the Bay of Monte Carlo, or the dark, shimmering car bodies at night silhouetted against the lights of the Sporting d’Hiver, there would be the diving boards and pontoons of these beaches outside Paris. But the light would be the same.

This rhyme between north and south, between the light of the Marne and that of the Riviera, suggests a spooky portability of mood, but also the futility of Jean’s attempt to start over in Nice. Devoted readers of Modiano will already have suspected as much. In Missing Person, a detective friend of the amnesiac narrator writes him from the southern city, where he has gone to retire: “Strangely enough, I run into people on the street I have not seen for thirty years, or who I thought were dead. We give each other quite a turn. Nice is a city of ghosts and specters, but I hope not to become one of them right away.”

Jean and Sylvia befriend a local couple named the Neals, who live in a dilapidated villa built by an American with wartime links to the Nazis. Here, as in many of Modiano’s later novels, the Occupation motif is not central to the story, but it adds a murky background to the Neals, who offer to buy Sylvia’s diamond. And indeed the wealthy couple are not who they claim to be. In the novel’s denouement—inconclusive, as Modiano’s endings tend to be—Jean and Sylvia’s past comes back to poison their present. As Jean reflects, with typically noirish wisdom, it is “as if the worm were in the apple from the beginning.”

Advertisement

A network of half-hidden connections runs through Modiano’s novels, as though they all belonged to the same fictional world, which intersects here and there with the author’s real biography (Modiano is often thought to be a pioneer of so-called autofiction). Phone numbers, addresses, and objects circulate from one book to the next. The phone numbers are often dead, however, and the addresses often belong to buildings that no longer exist. This is not the dense interconnectedness of Balzac’s Comédie humaine, with its ambition of representing all of French society. It is instead a skeptical, modern version, more interested in social misfits and missed connections, and distrustful of any pretension to survey the whole.

In Nice, Jean and Sylvia stay at the Sainte-Anne Pension. The owner is an older woman who speaks with a Parisian accent (Modiano’s novels are full of out-of-place accents, as though none of his characters are quite at home in their homes). Watching her feed caged birds in an old raincoat and headscarf, Jean wonders, “Her too—what accidents of chance had made her wash up in Nice?” Jean never follows up on his question, but here again fans of Modiano will have an advantage, since the pension owner’s story forms a chapter in an earlier novel, Such Fine Boys (1982), now available in Mark Polizzotti’s finely tuned English version (Modiano has been fortunate in his translators).

Such Fine Boys is a sequence of connected stories about the students of Valvert, a boarding school outside Paris. “It is always painful to see a child return to boarding school, knowing he’ll be a prisoner there,” Modiano writes in his memoir. “One would like to hold him back.” The students of Valvert are polyglot, privileged, and adrift—“accidental children, who belonged nowhere.” Their very names, tugging in different directions, suggest their rootlessness: Philippe Yotlande, Moncef el Okbi, Michel Karvé, James Mourenz (hybrid monikers are another hallmark of Modiano’s fiction—so many distant cousins of his own Franco-Italian name).

Valvert is not a terrible place in itself. The boys enjoy moments of camaraderie and are even fond of their teachers, who are strict but not inhumane. And yet all the boys are “prone to inexplicable bouts of melancholy.” The narrator is a Valvert alum who is mysteriously compelled to remember and in some cases to track down his former schoolmates to find out what has become of them. Toward the end of the book we learn, with a metafictional flourish, that the narrator’s name is Patrick and that he writes detective novels for a living.

The crime Patrick uncovers again and again is that of abandonment. Modiano has an agonized sensitivity to the ways in which parents guard themselves from their children: they hire proxies, offer bribes, withhold affection, retreat into their career or their marriage. In his memoir, Modiano tells the story of being a full boarder at a Parisian school, though his parents’ home was only blocks away. He also remembers “a Brazilian who for a long while occupied the bed next to mine, who’d had no news of his parents for two years, as if they had left him in the checkroom of a forgotten station.” But parental callousness is nowhere analyzed with such empathy and nuance as in Such Fine Boys.

In the novel’s most fully imagined episode, Patrick tells the story of Christian Portier and his mother, Claude, the woman who turns up as a pension-keeper in Nice in Sundays in August. When Patrick first meets Claude, during a weekend away from school in Paris, she is driving a Renault convertible and smoking Royale blondes. Her son, who is fifteen, introduces her with mock ceremony as the movie star Yvette Lebon. She isn’t a movie star, but the joke is telling—of how Claude wants to be seen, and how her son is eager to see her.

The pair is unusually intimate for a mother and teenage son: they banter and make evening plans together. Patrick later learns that Claude rents her son an apartment in the same building where she lives. “We decided not to get in each other’s way,” Christian explains suavely, but we come to see that, under the guise of granting him independence, Claude is keeping her child at a distance. When Patrick meets her twenty years later in Nice, he finds her unhappily married to an older man, surrounded by youthful photos of herself, and raising a flock of caged birds. She hasn’t seen Christian in years—he moved to Canada and cut her off. “Life is complicated,” she shrugs.

Modiano is an ethical writer, not a political one, and the poles of his moral imagination are negligence and care, the evil of abandonment and the virtue of solicitude. Such Fine Boys is a study in the varieties of self-absorption, or carelessness, and a reckoning of its costs. Seen in this light, the narrator’s devotion to his old school chums lends him a kind of halo, one that hovers over many of Modiano’s detective protagonists. In Modiano’s fiction, the crime of the war years was not France’s collaboration with Germany per se—he never condemns anyone, including his parents, for working with the Occupation—but rather the abandonment of its Jewish citizens and its reluctance to acknowledge the consequences of that decision.

To think of the Occupation in these peculiar terms is to drain that drama of its usual heroism. In his postwar writings, Sartre made the Occupation into an existentialist calvary. “Never were we freer than under the German Occupation,” he famously began one of his essays, meaning that the choice between collaboration and resistance was never more stark or unavoidable: “Every one of our acts was a solemn commitment.” In Modiano’s fiction (and in the exquisite film he helped to write with Louis Malle, Lacombe, Lucien), such choices rarely have to do with political principles. People collaborate simply to get by, or because they want an adventure, or because it is the path of least resistance. Modiano finds these motives more understandable, and perhaps more compelling, than purely ideological ones. Life is complicated.

The typical attitude of Modiano’s protagonists is not one of virile resistance, but passivity and drift. “I lived through the events I’m recounting,” he writes in his memoir, “as if against a transparency—like in a cinematic process shot, when landscapes slide by in the background while the actors stand in place on a soundstage.” Jean, the narrator of Sundays in August, uses precisely the same metaphor to describe his feeling of being at loose ends in Nice. Many of Modiano’s heroes describe themselves as sleepwalkers or ghosts. “Is it really my life I’m tracking down?” wonders the detective of Missing Person. “Or someone else’s into which I have somehow infiltrated myself?”

Modiano’s 2014 Nobel Prize speech is a reflection on his three central obsessions: the period of the Occupation (“a kind of primordial darkness”), the city of Paris, and the workings of memory. At the end of his lecture, Modiano mused that because he was born in 1945, “after the cities had been destroyed and entire populations had disappeared,” he was especially sensitive to the fragility of the past. This sensitivity sets his novels apart from the grand fictional projects of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, from the Comédie humaine to À la recherche du temps perdu:

I do not think that the remembrance of things past can be done any longer with Marcel Proust’s power and candidness. The society he was describing was still stable, a 19th century society. Proust’s memory causes the past to reappear in all its detail, like a tableau vivant. Today, I get the sense that memory is much less sure of itself…. We can only pick up fragments of the past, disconnected traces, fleeting and almost ungraspable human destinies.

The book that best illustrates Modiano’s ideal of the writer-as-rag-picker in the scrapheap of history is Dora Bruder (1997). This slim, unclassifiable work—part memoir, part forensic history, part occult séance—is Modiano’s most disquieting meditation on abandonment and rescue. It was inspired by Serge Klarsfeld’s Mémorial de la déportation des Juifs de France (1978), an archive of the names of some 76,000 French Jews deported during the war, and a work that caused Modiano, by his own account, to doubt the value of literature.

Dora Bruder recounts Modiano’s investigation into the life of a sixteen-year-old Parisian, the daughter of stateless Austrian Jews, who was—according to Klarsfeld’s Mémorial—deported to Auschwitz in the fall of 1942. Modiano comes across Dora’s name by chance in an old missing-persons notice in Paris-Soir, and his book is an attempt to save her from oblivion. Modiano’s archival labors are extraordinary, his recreation of Dora’s life is intensely moving, and yet his book leaves a troubling impression. From the opening pages, he insists on connecting his own life history with that of the murdered Jewish girl. In every neighborhood where Modiano uncovers a trace of Dora, he tells the story of his own memories of that place; he speculates whether she might have been caught in the same round-up as his father, and even shared the same Black Maria (he ultimately concludes they did not). Although presumably intended as gestures of solidarity, such contrivances make it seem as if Dora’s story had to be “infiltrated” by Modiano’s to be memorialized or made meaningful.

This emphasis on biographical connections casts doubt on Modiano’s ethic of rescue and remembrance, at least as an approach to writing history. It is too personal and idiosyncratic to answer the questions it quickly raises: What exactly makes anything or anyone deserving of remembrance? Are some things more deserving than others, and is there nothing that deserves to be forgotten? Why is it, for example, that Modiano’s memory makes so little room for France’s war with Algeria—a conflict, after all, with far fewer official memorials than World War II?

To make memory into a virtue is also to invite nostalgia, and Modiano’s recent fiction often lingers among the old cafés and empty boulevards, among photographic archives and fading soundtracks. “I feel as though I am alone in making the link between Paris then and Paris now,” he writes in Dora Bruder, “alone in remembering all these details.” But for all its details, Modiano’s Paris bears little resemblance to the contemporary capital of France: there are few Arabs, no cell phones (even televisions are rare), and no one visits the banlieus. Modiano’s appointment of himself as the memorialist of a vanishing Paris may help to explain the paradox of a writer who constantly reminds his French readers of a painful history while also being, arguably, the country’s most celebrated novelist. The enfant terrible has become the unlikely custodian of his city’s past—its charms as well as its crimes.

This Issue

November 8, 2018

MLK: What We Lost

The Concrete Jungle

‘Inventing New Ways to Be’