When he was young and dreaming of a career in cricket, long before he dreamed of being prime minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan was told to trim his ambitions. He wanted not just to play the sport professionally; he wanted to be a fast bowler, a niche talent in what Americans call pitching that consists of mastering the essential skill and craftiness of spinning, curving, and plotting the bounce of the ball, and then combining all this with the most intimidating possible speed.

Khan says he was told by coaches and peers that he simply had the wrong physique to be a fast bowler. But rather than accept the verdict, he set out to change his own shape. It took years of effort to develop the powerful shoulders and limber throwing arm needed to terrorize a stationary batsman, and to perfect the bounding, windmilling approach followed by a precision launch of the ball at up to ninety miles per hour. In the end, Khan rose to the pinnacle of cricket in Pakistan, where the sport comes a close second to religion in the passion it inspires. As a two-time captain of the country’s team in the 1980s and 1990s, he carried Pakistan to its greatest glory since the country’s independence in 1947: the capture of the Cricket World Cup in 1992. He also had the crowning good sense to retire from the game after that peak.

On August 18, following a national election in July in which his party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI, or Justice Party), won the largest number of seats, Khan was inaugurated as Pakistan’s prime minister. It might be said, however, that as a politician Khan has battled a handicap similar to the one he overcame in cricket: he is in many ways the “wrong shape” to lead a strategically important but poor, religiously conservative, and chronically troubled nation of 201 million that has slowly drifted toward the bottom rankings of human development indexes.

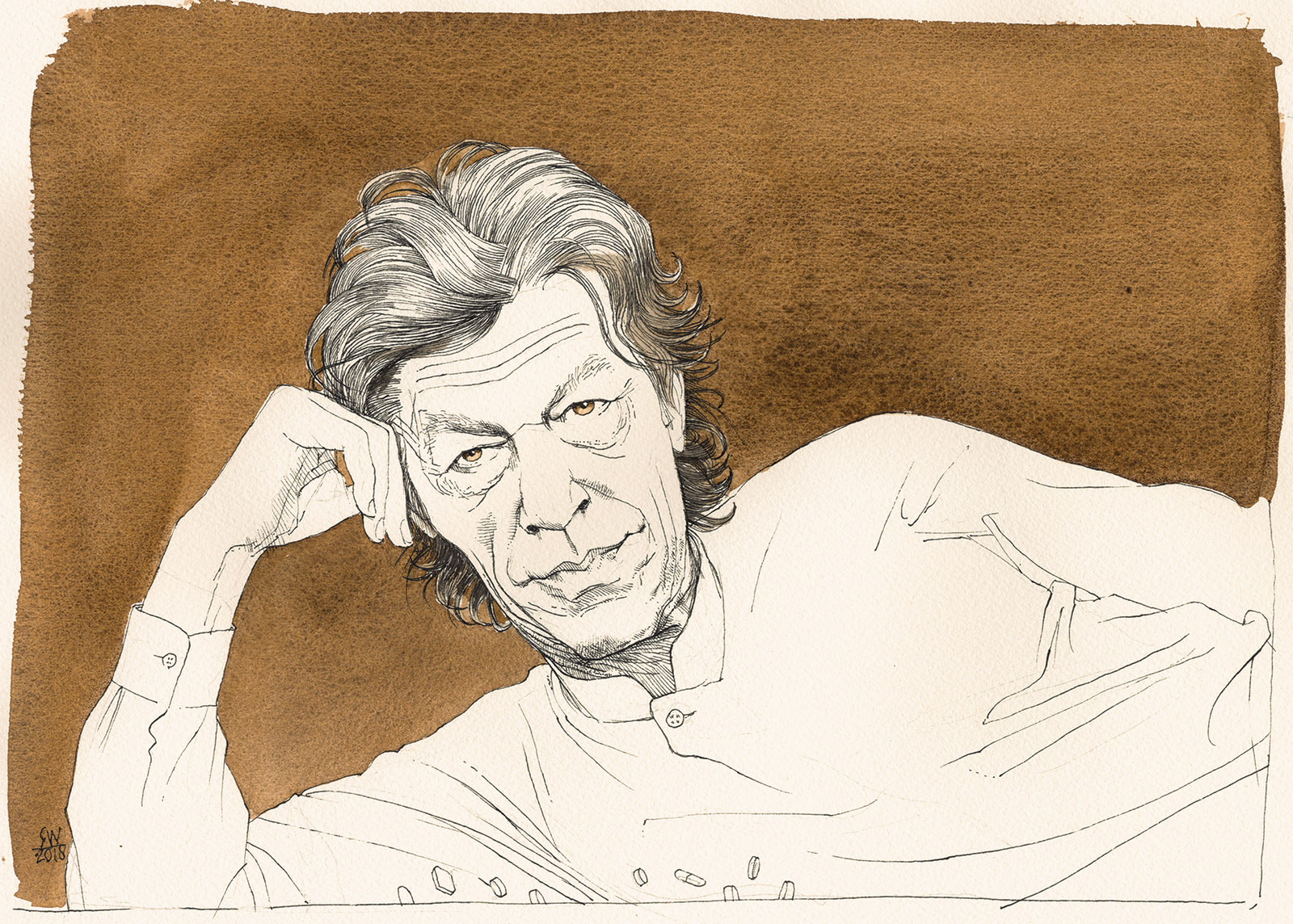

It is not simply that Khan’s long sporting career may have been poor training for statecraft. He is improbably posh for the rough and tumble of politics: he was educated in the vast green oasis of Aitchison College, Lahore’s most elite academy, as well as at an English boarding school and at Oxford (where he befriended another future prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, and did, in fact, do a politician’s prep as a student of PPE—philosophy, politics, and economics). Khan looks less like a fresh-scrubbed politician or a tough potentate than like a rumpled, aging rock star, which is not surprising since he gained tabloid notoriety in the 1980s and 1990s as an international playboy. Among numerous well-publicized romances was his first marriage, to Jemima Goldsmith, who was two decades younger and the daughter of a very rich (and part-Jewish) English financier of just the sort to raise harrumphs among the conspiracy-minded, a type well represented in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

Over the twenty-two years since Khan founded his political party he has worked assiduously to remold his public image. The new one presents striking counterpoints to those initial political handicaps. When it comes to Khan’s sporting past, for instance, Pakistanis are reminded not that he may be handier with a cricket bat and ball than with a microphone or legislator’s pen, but rather that he was Pakistan’s kaptaan, the clear-eyed, loyalty-commanding captain of a winning national team. As Khan likes to boast, he twice resigned that position when others tried to interfere with his game plans. In other words, his sporting experience proves his credentials for leadership, suggesting that, unlike ordinary, craven politicians, Khan will always be his own man, someone who will stand up to foreign meddlers and overweening Pakistani generals alike.

As for being too upper-class or good-looking or oversexed, these attributes simply mean that Khan will prove irresistibly charming to devious foreigners, in stark contrast to previous portly and unsmiling prime ministers. On the question of wealth, Khan has so relentlessly attacked his rivals as corrupt and feudal-minded that many Pakistanis seem to overlook the fact that his PTI party has in fact embraced rich, feudal “electables”—as candidates enjoying bought or secure constituencies are known in Pakistan—with much the same glee as other parties. Khan lives in a spectacular mansion in the hills above Islamabad, but as everyone knows, he never carries a wallet, does not have a car registered in his name, and includes four goats among the assets listed in his mandatory tax declaration. The image he projects is of a man who has everything but needs nothing. He once challenged the Indian journalist Karan Thapar with the question—since he is a man who already has everything he wants—“Can anyone buy me? Can anyone tempt me with anything?”

Advertisement

To assuage the anxieties of those who might accuse Khan of hobnobbing with cosmopolitan intriguers and enemies of the faith, the former playboy has worked relentlessly to build an impeccably ultra-conservative record on “Islamic” issues. He has stoutly defended laws that punish blasphemy with death, and that single out the heterodox Ahmedi sect for persecution. He has disparaged “Western feminism” for “degrading the role of mothers.” He has questioned al-Qaeda’s responsibility for the September 11 attacks, and has repeatedly condemned America’s ostensible demands for Pakistani subservience, furiously blasting its policy of targeting suspected terrorists with drone strikes.

Wits have dubbed him “Taliban Khan” not only for his praise of the Afghan brand of militant Islam, but also for his description of the even more murderous, obscurantist Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan as “misunderstood.” This despite the group’s claims of responsibility for tens of thousands of deaths in hundreds of terrorist attacks, such as one on a boys’ school in Peshawar in 2014 that left 132 children dead. Khan describes his political philosophy as one of Islamic socialism. He has sought the blessing of revered religious figures, performed great works of charity, and recently married a woman renowned as a spiritual guide and healer. Surely, then, he is a deeply pious man?

If one is to believe his second wife, Reham Khan, who was married to him between November 2014 and October 2015, the answer is a resounding No. Her detailed but highly readable memoir was published shortly before the election. Reham Khan is something of a politician’s worst nightmare: imagine an erudite Melania Trump in full vindictive vent, writing a tell-all demolition of Donald.

Reham Khan (the last name is her first husband’s, not Imran Khan’s) gives plenty of reasons for her ire. Before meeting him she had, through sheer determination, wrenched herself and three children away from a catastrophic traditional early marriage—at nineteen, to a bullying cousin—and built a successful career as a television presenter, first in England and then in her native Pakistan. In her telling, Imran Khan went out of his way to charm and seduce. He sold himself as a passionate lover, a man of integrity, and an idealistic politician. He flattered her with a vision of her own future position as a woman of moral rigor who could reenergize his party. When he gained his rightful throne as prime minister, she would be his glamorous queen.

It all unraveled spectacularly. Reham Khan accuses the great man of a plethora of minor flaws: he is callous to animals; he is embarrassed about his hair implants; he tells the same boring stories over and over; he is superstitious enough to slather his whole body in dal—cooked lentils—to ward off envy, on the advice of a quack healer; he is callow; he is venal; he thrives on gossip; he is duplicitous; he is so lazy that his typical working day is barely three hours long; he “pleasures himself” while watching gay porn; he is not at all as well-endowed as people assume (she quotes a Bollywood star whom Khan is said to have bedded saying he was “big talk and small delivery”).

If her account is to be believed, she reveals much more damning sins, too. As the months on Khan’s grand estate in the hills above Islamabad passed and she started tallying his long absences in the bathroom, odd phone calls, and mysterious packets and vials forgotten in pockets and drawers, she claims that she began to realize that her husband was not merely a recreational user of drugs, but seriously drug-dependent. “The typical day’s cocktail,” she writes, “would generally consist of half an ecstasy tablet and one or two lumps of coke, followed by two to three sedatives at night.” The pills included such potent downers as Rohypnol, and the coke intake may have been as much as six grams in a day. At one point in the book Khan rolls up a cigarette laced with black tar heroin. He tells her he wears a tooth guard in bed because he grinds his teeth in his sleep; she concludes it is because of the jaw-clenching reflex induced by the drugs.

Far from being a paragon of Muslim piety, her husband, she claims, rarely attended public prayers, had never read the Koran, and was not even familiar with its better-known passages. He was sloppy with his daily ablutions. He played loud music during Ramadan. He occasionally drank alcohol and continued to pursue extramarital affairs.

Such lack of punctilio bothered his deeply religious wife, but it was Khan’s lapses as party leader that turned her doubt to disgust. She apparently found him sucking up to unsavory financiers, turning a blind eye to manifest corruption, punishing whistleblowers, and accepting gifts and sweet property deals for himself; she also notes the rapid waning of his initial enthusiasm for involving his attractive, well-spoken new wife in his campaigns, in part because he began to resent her growing celebrity, and because he chafed at her growing disapproval.

Advertisement

As their marriage came under stress, she writes, Khan cut her without warning or discussion out of party work, and then increasingly out of his life. He did not inform her until the night before leaving of a week-long trip abroad. The final straw came with her discovery, by the accidental revelation of a phone message, that her husband, even while telling her they must give their marriage another chance, had in fact secretly engaged an ex-girlfriend to contact Reham Khan’s ex-husband to see if the two men could act in concert to get lawyers to impose a gag order on her once he divorced her.

After confronting Khan, who responded by clutching his head in his hands and begging forgiveness, she took a long shower. “I felt like a woman who had been raped in public,” she says. She departed immediately for England on a previously planned trip to see her children. A day later, sleeping on a friend’s floor in London, she found out that Khan had had all her possessions unceremoniously removed from his country mansion.

It is easy enough to question the reliability of an angry ex-wife. This is particularly true if she happens to be left, as Reham Khan seems to have been, with very limited resources in another country, with children to support, and no prospect of court-ordered compensation. Reham Khan is also now a de facto political exile: in a place as violent as Pakistan, it would be unwise to take lightly the bitter accusations that she now faces of having betrayed and defamed a popularly elected prime minister.

There are subtler reasons to raise questions about her account, too. It appeared just in time to potentially damage Imran Khan’s electoral chances. Considering that its author claims to have long shared the political ideals represented by the PTI, it seems odd that she now chooses not only to condemn her former party but to shower particular praise on its biggest enemies, the “corrupt” and “dynastic” leaders of rival parties. Her book’s occasional digressions into self-praise, and particularly self-congratulation for high-minded patriotism and piety, give an impression of self-righteous smugness rather than objectivity. A sympathetic editor might have suggested leaving out a passage such as one in which Khan tells her, “I have never met a woman like you. So upright, so courageous. Only you can guide me.”

Yet in crucial ways it does not really matter whether Reham Khan is our ideal guide. Many of the character flaws she notes in her ex-husband have been long and widely rumored. Her layering of detail simply underlines some unfortunate and well-known facts about the nature of Pakistan, a country where the pageantry of elections and politics has only ever played out within a sphere tightly circumscribed by the true power in the land, the army.

However much Khan may insist he is his own man, everyone knows that there are red lines that civilians cannot cross: the military’s privileges and “strategic” prerogatives, including the cloak-and-dagger games it plays with terrorist groups, are out of bounds for criticism.* Everyone also knows that Khan could never have reached the prime minister’s office without not only the tacit but also the active backing of the army. Not surprisingly, instruments of state such as the powerful propaganda branch of the army were widely accused of tipping the scales for the PTI in the recent election.

Why should Pakistan’s “deep state” favor Imran Khan? An obvious reason is that he has gone out of his way to toe its line, with his mix of strident patriotism and conservatism. Another is that his celebrity status helps to sustain the useful fiction that civilian politics matter, and also helps to pull a stubbornly fissiparous country together: seventy years after independence, none of Pakistan’s political parties aside from the PTI has a serious national, rather than merely regional, presence. The two previous ruling parties, the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) (PML–N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), are dominated by two big families, the Sharifs and the Bhuttos, and now hold sway only on their respective turfs in Punjab and Sindh.

What Reham Khan’s account suggests is that there may also be a darker reason for the deep state’s support. Given the reach and complete unaccountability of Pakistan’s intelligence services, their accumulated files on her ex-husband must be voluminous indeed. To hold an encyclopedic record of Imran Khan’s peccadilloes, trysts, and consumption of drugs would be to hold a sword of Damocles over his political career. This vulnerability would render someone like Khan not just a useful asset but an ideal candidate for leadership.

Should the new prime minister imagine straying beyond the deep state’s bounds, he might be reminded of the fate of his civilian predecessors. Not one of Pakistan’s previous eighteen prime ministers has been allowed to complete a full term in office. The last elected prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, was, like Khan, accused early in his political career of being a stooge of the army. Several decades in politics and three stints in the premier’s office later, Sharif and his party had grown rich and haughty, and showed a mild inclination to cross the red lines. In October 2016 an aide leaked details of a meeting in which Sharif complained to army generals that their insistence on providing cover to militant Islamist groups was damaging Pakistan’s standing in the world. The civilians were forced to bluster denials and apologies about the meeting, but a breach had clearly opened.

Relations between the prime minister and the army grew increasingly strained, until last summer Pakistan’s Supreme Court abruptly declared Sharif unfit for office, on grounds that he had failed to declare income from a position that he held, on paper, in a company owned by his son—money that he had, in fact, never received. He was forced to resign. Earlier this year the judges effectively ended his career, announcing that his supposed violation of Pakistan’s constitution meant he could no longer hold elected office. Sharif is currently in prison, appealing a ten-year sentence for separate corruption charges.

In relation to Imran Khan, the irony here is particularly rich. It is no secret that Sharif’s already wealthy family profited greatly from his years as Pakistan’s top politician. Yet the specific misdemeanor that prompted the country’s highest court to topple him was a violation of a vague constitutional requirement that elected public servants be “truthful and trustworthy.” In a 2007 interview, when Khan, accused of fathering an illegitimate child, faced down a similar motion under the same articles, he dismissed the requirement as impossible to fulfill. “You literally have to be an angel to pass this,” he protested. If even a part of what his ex-wife alleges is true, Imran Khan is no angel.

Curiously, for all her determination to reveal the manifold hypocrisies of her ex-husband, Reham Khan seems strangely shy about turning the same objectivity to the bigger problems of Pakistani society and politics. Only very obliquely does she refer to the control the army exerts over public affairs. In Pakistani television, she notes, “most of the well-known anchors were romanced by the media wing of the intelligence services.” Her own meeting at the request of a top army officer “ended with my polite refusal to work under their direction but we did continue to share ideas on film topics.” General Hamid Gul, a hawkish former head of Pakistani intelligence and an architect of its backing for radical Islamists, took an interest in her career, she says, only to object vehemently to her relations with Khan. She claims that shortly before they wed, the general text-messaged Imran Khan a blunt order: “Abort the marriage!!!” For the ex-intelligence chief to feel entitled to pronounce so boldly on the future prime minister’s private affairs suggests a peculiarly intimate relationship.

When Imran Khan in 2014 mounted a noisy sit-in to charge Nawaz Sharif with vote rigging and corruption, it seems to have occurred to her that hidden hands may have encouraged him to undermine the civilian government. “You do realize that you will be used and discarded like toilet paper?” she claims to have told Khan. “Nawaz will be controlled and so will you.” Her husband ignored the advice, but the part about Sharif certainly did come true.

This form of shadow puppetry, where participants understand the reality of the theater but continue to act out the play, is very much a feature of public life in Pakistan. Reham Khan shows a similar and rather telling reticence to confront basic issues when it comes to religion. Islam, she declares, “is not a religion that comes in shades…it is clear about what is permitted or forbidden.” Elsewhere she claims to have explained to Imran Khan that the beauty of Islam lies in the fact that there is no middleman; every Muslim can read the Koran to avoid “any misinterpretation or misinformation.” Unfortunately, it is precisely the effort to sustain such a pretense of uniformity and clarity in meaning that has so often pushed not only Pakistan, but its neighbors Afghanistan and Iran, into violence.

For a deeper understanding of such pathologies there are few better guides than Husain Haqqani. Like Reham Khan, Haqqani, the former Pakistani ambassador to the US, made the unfortunate discovery that proximity to power and an inclination toward truthfulness can land one in hot water in Islamabad. Haqqani was close to all sides of Pakistani political power at one point or another. A former student member of the conservative Islamist political organization Jamaat-e-Islami, he has also worked as a journalist, a policy adviser, and a government spokesman.

He was at his post in Washington in May 2011 when US Navy Seals helicoptered into Abbottabad, deep inside Pakistan, to kill Osama bin Laden. As Haqqani struggled to maintain the official bluster about such a shocking breach of Pakistani sovereignty, he found himself accused in Islamabad of having betrayed his country. Specifically, the deep state tied him to an alleged memo addressed to the Obama administration, which was said to have advised America to leverage Pakistani embarrassment over the disclosure that the world’s most wanted fugitive had lived comfortably in an area favored by retired senior officers, and to pressure the army to cede more power to civilians. In other words, he was accused of showing too much concern for Pakistan’s elected government and not enough for its generals.

Haqqani denies having written any such memo, but was forced to resign his post and has effectively lived in exile since 2012. He is now a prolific commentator and a fixture on the think tank circuit. In three previous books he has cogently and succinctly explored Pakistan’s military and its two most important and also most fraught foreign relationships, with India and America. His new book, Reimagining Pakistan, has a broader focus. It is an ambitious attempt to lay out an almost forensic analysis of Pakistan’s troubles and then to suggest cures.

As a diagnostician, Haqqani excels. Building on specialist literature as well as a range of writings, from Barbara Tuchman on historical folly to Irving Janis on the dangers of groupthink, he traces the evolution of the varied myths and obsessions that have confounded Pakistan back to their origins in the country’s formative years. Haqqani does not shy from ascribing blame. Fellow Pakistanis bear the brunt of it, but the dangerously narrow interests and myopia of America’s engagement with the region come in for a fair share. Haqqani notes that US aid to Pakistan has spiked during each of the three periods the country has fallen under direct military rule.

As a useful and wide-ranging compendium about Pakistan, Haqqani’s book makes for an excellent introduction. There is not much that is really new here, however. More disappointingly, the book fails to live up to its title’s promise of prescribing fixes for the country’s ailments. Only a few paragraphs out of three hundred pages really propose any “reimagining” of Pakistan, often with sweeping statements such as: “To end its march of folly, Pakistan needs to reassess its core beliefs about a religion-based polity, reconsider the notion of permanent conflict with its larger neighbor, recreate political institutions to reflect its ethnic diversity and rebuild its economy without reliance on the largesse of others.”

Doubtless Haqqani is correct in spirit, but he also quotes the scholar Stephen Cohen, who wrote in 2006 that, whatever may be desirable for Pakistan, it is the army that “will continue to set the limits on what is possible.” That constraint seems unlikely to shift under a new prime minister, despite his promise to create a naya, or new, Pakistan. Imran Khan faces another, chronic constraint, too: a weak economy desperately short of investment capital. Not only is Pakistan poor and deeply in debt. Its trade deficit has swollen alarmingly in recent years and its reserves have sunk, leaving it increasingly dependent on a handful of benefactors such as Saudi Arabia and, especially, China.

For all Imran Khan’s talk of creating an Islamic welfare state, he has had to devote his first months in office to scrambling for cash. Fearful of over-reliance on Pakistan’s giant northern neighbor, whose province of Xinjiang currently hosts upward of a million of its own Muslim citizens in “reeducation” concentration camps, he has approached the IMF for a $12 billion bridging loan. The international lender will prescribe medicine far harsher than the theatrical austerity measures that Khan’s government has already announced, such as ordering ministers to serve only tea and coffee at their functions, and to print on both sides of paper. Having at last gained control of the ship, Captain Pakistan may find that rearranging the deck chairs is not going to save it.

This Issue

November 22, 2018

A Very Grim Forecast

Romanticism’s Unruly Hero

The Crash That Failed

-

*

See Ahmed Rashid, “Pakistan’s Jihadi Proxies,” The New York Review, September 27, 2018. ↩