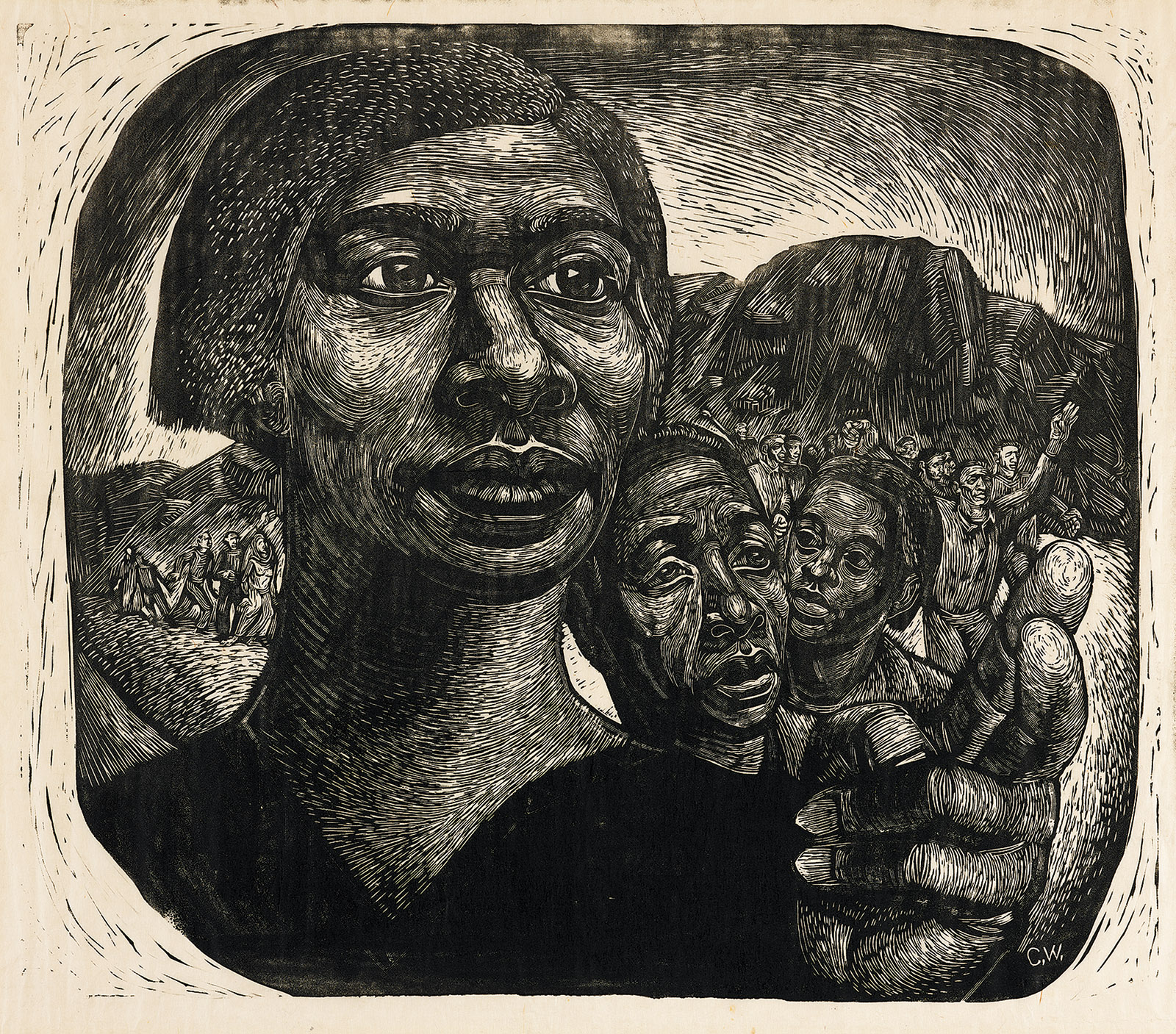

Philadelphia Museum of Art/Charles White Archives

Charles White: Exodus I: Black Moses (Harriet Tubman), 1951; from the exhibition ‘Charles White: A Retrospective,’ on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, until January 13, 2019. The catalog is published by the Art Institute of Chicago and MoMA and distributed by Yale University Press.

In January 1850 Senators Andrew P. Butler of South Carolina and James Mason of Virginia proposed a new Fugitive Slave Law to replace the statute that had been on the books since 1793. A new law was needed, they said, because the old one was not being enforced. Free black communities in northern states routinely sheltered runaway slaves. For decades an alliance of free blacks and white abolitionists had been operating an Underground Railroad that assisted thousands of slaves escaping from the southern states. In cities and towns across the North countless white citizens and local police officials refused to assist in fugitive slave renditions.

Northern legislatures had passed a series of “personal liberty laws” designed to thwart the federal statute. Some of those laws banned state and local officials from participating in renditions. Others closed state and local prisons to slave catchers. Most often, however, the personal liberty laws mandated jury trials and habeas corpus for blacks accused of being runaway slaves, mandates the slaveholders considered an assault on their constitutional right to reclaim their slave property. Although many Northern whites sympathized with the slaveholders or viewed it as their legal and constitutional duty to enforce the law, even those who cared little about slavery were often repulsed by the specter of slave catchers swarming into their communities and enforcing Southern law in Northern states.

The new Fugitive Slave Law created a body of federal commissioners empowered to impose federal authority on the North, bypassing obstreperous state and local officials. Slave owners were required to provide only minimal proof of their claims. Those accused were stripped of due process and denied any right to appeal a commissioner’s ruling. Commissioners were paid five dollars if they ruled against the slaveholder and ten dollars if they ruled against the fugitive. There was no statute of limitations. African-Americans who had built families and worked as free people in the North for decades were vulnerable to reenslavement at any time. If there were signs of local opposition, federal marshals could conscript Northern citizens into a posse, forcing them to participate against their will in the capture and return of alleged fugitives. Heavy fines were prescribed for anyone convicted of helping slaves escape.

Senator William Seward of New York and other opponents of the proposed law warned Southerners that it could not be enforced in Northern states. Salmon P. Chase of Ohio predicted that the law would “produce more agitation than any other which has ever been adopted by Congress.” Even Butler, the bill’s cosponsor, doubted that it would ever be enforced. Robert Barnwell Rhett of South Carolinia questioned the efficacy of a law that clearly contradicted the “opinions and feelings of the [Northern] community.” Jefferson Davis of Mississippi had no faith that a mere statute could overcome the widespread hostility to slavery in the North.

But in the end nearly every Southerner in both houses of Congress supported the bill, while most Northern congressmen voted against it or else absented themselves rather than vote for it. In late September, after months of rancorous debate, a slim majority in the House approved it and President Millard Fillmore signed the new Fugitive Slave Act into law. It was one of several bills passed as part of the so-called Compromise of 1850. Party leaders hailed the measures as the “final settlement” of all the controversial issues related to slavery, but that was a fantasy. The hostile Northern reaction to the Fugitive Slave Law was as swift as it was severe.

In most historical accounts, the 1850 law provoked a wave of panic in free black communities across the North. Hundreds of African-Americans fled their homes for the safety of Canada. But Richard Blackett’s extraordinary new book, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, tells a more complicated story. The flights to Canada were terrifyingly real. “Fugitives and their families fled in droves in the days and weeks after the law’s adoption,” Blackett writes. “Forty left Boston in three days.” But along with waves of panic came waves of defiance. “I don’t respect the law,” declared Jermain Loguen, a black leader in Syracuse who had escaped from slavery years earlier. “I don’t fear it—I won’t obey it!” Samuel Ringgold Ward, a black abolitionist pastor, urged Bostonians to make any attempt to enforce the law “the last act in the drama of a slave-catcher’s life.” Henry C. Wright, a white abolitionist, told listeners in Cleveland that if he were a fugitive he would readily “plunge a knife into the heart of his pursuer.” Scores of protest meetings—168 by Blackett’s count—erupted all across the North in late 1850 and early 1851. Critics denounced these “mongrel gatherings” of whites and blacks that sprang up in “every city, and nearly every village of the North.”

Advertisement

Blackett has identified over 140 fugitive slaves whose cases came before commissioners in the fifteen months after the law was passed. Of those only seven were freed. Ninety-eight were returned to slavery, and thirty-three escaped or were rescued. But those statistics are misleading, Blackett shows, because the law never reached most fugitive slaves. Thousands managed to escape into a free state and make their way to one of the hundreds of free black communities that dotted the Northern landscape. Those communities were not only a safe haven for fugitives from the South, they were also places that slave catchers approached at the risk of their lives. The arrest of an escaped slave invariably aroused local blacks who quickly formed crowds outside courtrooms and jailhouses, intimidating judges and sheriffs. At Christiana, Pennsylvania, a group of armed black men fought off a group of slave catchers, killing a slave owner and wounding his son. In Pittsburgh it was reported that “escaped slaves have all armed themselves and declare that they were resolved to die rather than be again carried into bondage.” In Syracuse an organized mob stormed the police station and rescued a fugitive named Jerry from his captors.

In many Northern communities it was impossible to find men willing to serve as commissioners, and those who did serve were often ostracized or so harassed that they soon resigned. Organized protest meetings passed resolutions denouncing commissioners as “moral nuisances, contaminating the air of freedom” and a “putrid, moral pestilence.” Charles Stetson, the federal commissioner in Cleveland, publicly swore never to enforce the 1850 law, and there is no recorded case of any slave being returned from Cleveland for the entire decade. The law was supposed to make fugitive slave rendition easier, but antislavery lawyers repeatedly clogged the system with delaying tactics that made the process slow and expensive. Northern juries acquitted those accused of assisting runaway slaves. Threatened by crowds of protesters, local officials who called out a posse sometimes faced wholesale refusal to participate. The law was most strongly supported and enforced in cities like New York, with strong commercial ties to the South. But as Blackett points out, “the new law was a dead letter, unenforceable where, as in Buffalo, it did not meet with public approval.”

Supporters of the law claimed to be scandalized by the opposition it aroused, despite the numerous warnings that it could not be enforced. Clay was especially disgusted by the organized activity of African-Americans. The Compromise of 1850, he said, was under assault from people “who possess no part…in our political system.” He dismissed black activists as the mere “catspaws” of abolitionists. Daniel Webster denounced whites as well as blacks who resisted the law. “They are traitors,” he complained, “and are guilty of treason.”

The federal government marched thousands of troops into Northern cities and spent vast sums of money in its overbearing effort to enforce the law. When slave catchers caught up with Thomas Sims after he escaped from a rice plantation in Georgia, antislavery advocates used every conceivable legal tactic to thwart his rendition. Determined to make an example, President Fillmore authorized the expenditure of between $10,000 and $20,000 to pay for the troops required to send Sims back into slavery. In Syracuse, the trials of those accused of rescuing Jerry took two years and cost the federal government $50,000.

A very different reaction to the controversy was a revival of interest in proposals to colonize Liberia with former slaves. Clay, a longtime supporter of colonization, endorsed the establishment of a federally funded steamship line to transport free blacks to Africa “with their own consent.” The proposal went nowhere. Deep South slaveholders objected to anything that even hinted at federal support for emancipation, and many Northern Democrats agreed that it was none of the federal government’s business. As a consequence Washington had for decades barely funded colonization. Most of the government money came from the states, especially from Maryland and Virginia, which in 1853 appropriated $18,000 per year for five years—the largest state authorization ever. Indiana’s total of $5,000 was more typical, but most states never appropriated any funds for colonization. And most of the politicians who voiced support for the idea insisted that colonization be strictly voluntary.

This last specification doomed the entire project because African-Americans had almost no interest in voluntary emigration from the land of their birth. As Blackett shows, in the immediate aftermath of the state’s appropriation only a handful of Indiana blacks took advantage of the subsidies, and after 1855 none did. In the forty years leading up to 1860, by which date there were 57,000 free blacks living in Pennsylvania, fewer than 300 emigrated to Liberia. For all practical purposes, voluntary colonization meant no colonization.

Advertisement

Most of The Captive’s Quest for Freedom—seven of twelve chapters—consists of a series of state and regional studies of the fugitive slave crisis as it unfolded during the 1850s. Not surprisingly, most of the conflict took place in the border regions between slave and free states. Fugitive slaves crossed from Missouri into Illinois, from western Kentucky into Indiana, and from eastern Kentucky into Ohio. The long southern border of Pennsylvania—the famous Mason-Dixon Line—was a particularly attractive refuge for fugitive slaves, and Blackett devotes an entire chapter to it. Another chapter traces the course of fugitives from the Eastern Shore of Maryland to Philadelphia. But two more chapters move the story deeper into the Northern states of New York and Massachusetts.

In these chapters political history gives way to social history as Blackett skillfully reconstructs dozens of stories of slaves escaping to the North. Some of these escapes and rescues are well known, but they take on renewed salience in Blackett’s account because of the wider setting he establishes. More impressive is the deep and meticulous research that has enabled him to piece together the remarkable stories of previously unknown cases. As the chapters proceed and the stories pile up, they are sometimes repetitive, but their cumulative effect is overwhelming. They lend credence to Blackett’s argument that fugitive slaves themselves played a central part in the politics of slavery in the critical decade before the North and South went to war.

Antislavery politicians denounced the 1850 law for its failure to secure the due process rights of accused runaways. Clay responded to this criticism by proposing that jury trials be allowed in the South, in the places from which the slave had escaped, but the slaveholders killed the idea. Seward countered that jury trials had to be convened in the Northern communities where the accused was seized. Anything else would not guarantee a fair and impartial hearing. William Dayton of New Jersey proposed that “in all hearings before commissioners, depositions had to be authenticated and proof provided that the person claimed was a fugitive.”

Insisting on extensive documentary proof quickly became another means of thwarting the law. Antislavery lawyers appeared at hearings where they grilled slave catchers and demanded verification of the alleged fugitive’s identity.1 In mid-November, only weeks after the 1850 law was passed, the Vermont legislature enacted a statute of its own, guaranteeing accused fugitives a jury trial and habeas corpus. Virginia’s governor, John B. Floyd, denounced such “gratuitous intermeddling with our slaves”; Vermont’s and similar laws were “nothing short of open rebellion and utter defiance.” Blackett’s conclusion seems indisputable:

When measured by how effective it was in returning runaways, the law left a great deal to be desired. And more alarming, renditions generally produced a firestorm of protest in the cities and towns where they occurred….By the end of the first year of the law’s operation it was clear to all dispassionate observers that, rather than quieting agitation over slavery as so many of its proponents had hoped, it had stirred passionate opposition and defiance.

Blackett’s larger point, equally persuasive, is that although the Fugitive Slave Act was ineffective it was hardly insignificant. One of the many strengths of The Captive’s Quest is its appreciation of the political as opposed to the statistical significance of fugitive slaves. Though he resisted the suggestion to call his book Fugitive Slaves and the Coming of the Civil War, he makes the point himself in the preface: “The crisis caused by escaping slaves was not enough to bring on the Civil War, but there is no doubt that it was a major contributing factor.” Blackett returns to this issue, and to politics, at the very end of his book. He notes that the first major congressional speech Charles Sumner gave as a senator from Massachusetts was a ringing condemnation of the Fugitive Slave Act. And although Blackett does not emphasize the point, his evidence suggests that fugitive slaves exposed a partisan divide in Northern politics. By the time the Civil War broke out, it was widely understood that Democrats would return fugitive slaves but Republicans would not.

Yet as far as Blackett goes in linking fugitive slaves to the political crisis of the 1850s, there is still more that can be said. When he turns his attention to individual states, Blackett largely abandons the political history of the fugitive slave controversy, even though most of it took place in the states. It was the personal liberty laws passed by Northern states in the 1840s that had prompted Southerners to demand a more aggressive Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, and once the new federal law took effect those same Northern states responded with another round of personal liberty laws. Over the course of the decade street protests gave way to assaults by state legislatures on the Fugitive Slave Act. Fixated on the struggle over slavery in the territories and overly impressed by Southerners who wrapped themselves in the misleading mantle of states’ rights, historians have greatly underestimated the significance of Northern defiance of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Political opposition focused on what seems at first glance a narrowly legalistic demand for jury trials for accused fugitives. But like the dispute over slavery in the territories or abolition in Washington, D.C., the debate over due process rights for accused fugitives was a kind of proxy fight. Because nearly everyone on all sides agreed that the Constitution did not allow the federal government to abolish slavery in a state, antislavery politicians tried to undermine slavery wherever they could. Blocking fugitive slave rendition was one such way, and the call for due process was particularly threatening. Due process was widely regarded as one of the “privileges and immunities” of citizenship, so the demand that accused fugitives be guaranteed a jury trial was an implicit recognition of black citizenship.

Southerners were fully aware of the subversive implications of due process. When Seward proposed an amendment to guarantee jury trials in the North for accused fugitives, Maryland Senator Thomas Pratt denounced it as “a practical denial of the whole right of the slaveholder over his slave, if he gets beyond the jurisdiction of his own State; because everybody knows,” Pratt continued, and “the honorable Senator from New York himself knows” that fugitive slaves were being “discharged” by New York courts on the flimsiest of pretexts. “Of all the subjects doing harm at the South,” Pratt added, “the escape of fugitive slaves is doing the most harm,” and was “the most calculated to excite the public mind.”

In 1854 Abraham Lincoln began to signal his endorsement of Seward’s approach. Lincoln believed that the presence of a fugitive slave clause in the Constitution implied a federal obligation to enforce it. The question was how. Lincoln preferred a statute that “did not expose a free negro to any more danger of being carried into slavery, than our present criminal laws do an innocent person to the danger of being hung.” Over the next several years Lincoln would repeat his call for revisions to the 1850 statute, to remove what he called its “objectionable” provisions—not only the absence of due process protections for accused fugitives, but the obnoxious requirement that northern civilians participate in fugitive slave renditions.2

In 1859 Lincoln went even further and warned that secession would bring a halt to all fugitive slave renditions in the Northern states. In a speech in Cincinnati, he declared that if any states seceded from the Union in response to a Republican victory in the 1860 elections, Northerners would be relieved of any constitutional obligation to return fugitive slaves. The Southern states complained, he said, that Northerners made it difficult for owners to recapture their fugitive slaves. But, he asked, “do you think you can better yourselves on that subject by leaving us here under no obligation whatever to return those specimens of your movable property that come hither?” The South was threatening to break up the Union because “we would not do right with you” in the rendition of fugitive slaves, but “when we cease to be under obligations to do anything for you, how much better off do you think you will be?”

After he was elected president in November 1860, Lincoln renewed his call for substantial revisions of the 1850 law to guarantee due process rights to suspected fugitives and restrict enforcement to federal officials, absolving Northern states and civilians of any obligation to participate in the capture and return of fugitive slaves. There was nothing at all unusual about his proposal. Antislavery politicians had been demanding due process rights for accused fugitives for at least a decade.

You don’t have to spend much time reading secessionist speeches and editorials to appreciate why Lincoln’s proposal for a federal personal liberty law was more likely to inflame than to calm the South. The very first item in South Carolina’s declaration justifying its withdrawal from the Union listed by name fourteen Northern states that had passed personal liberty laws. Those laws, the Carolinians declared, “either nullify the Acts of Congress or render useless any attempt to execute them.” Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown asked why the South should remain in the Union: “Will the Northern States repeal their personal liberty laws? No.” More to the point, the personal liberty laws were but a symptom of a much larger problem, as Stephen Hale explained to Governor Beriah Magoffin of Kentucky. Hale was the commissioner sent by Alabama to persuade Kentucky to secede. Among the reasons he gave was the fact that the Fugitive Slave Act

remains almost a dead letter upon the statute book. A majority of the Northern States, through their legislative enactments, have openly nullified it, and impose heavy fines and penalties upon all persons who aid in enforcing this law…. The Federal officers who attempt to discharge their duties under the law, as well as the owner of the slave, are set upon by mobs, and are fortunate if they escape without serious injury to life or limb; and the State authorities, instead of aiding in the enforcement of this law, refuse the use of their jails, and by every means which unprincipled fanaticism can devise give countenance to the mob and aid the fugitive to escape.

Lincoln responded to these complaints by reiterating his proposal for a federal personal liberty law in his inaugural address. “There is much controversy about delivering up fugitives from service or labor,” he began. Everyone who swore an oath to the Constitution was of course swearing to uphold the fugitive slave clause. The problem was the draconian fugitive slave law, which he wanted to replace. “In any law upon the subject,” he suggested,

ought not all the safeguards of liberty known in civilized and humane jurisprudence be introduced, so that a free man be not, in any case, be surrendered as a slave? And might it not be well, at the same time, to provide by law for the enforcement of that clause of the Constitution which guaranties that “the citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the several states?”

As long as the 1850 law remained on the books it should be obeyed, Lincoln said, but there were some laws that communities found so morally offensive that they would never be fully obeyed. The Fugitive Slave Act, he conceded, was “as well enforced, perhaps, as any law can ever be in a community where the moral Sense of the people imperfectly supports the law itself.” And secession would only make the already lax enforcement of the fugitive slave law even “worse,” Lincoln warned, because “after the separation of the sections…fugitive slaves, now only partially surrendered, would not be surrendered at all.”

Ten weeks later Lincoln called his cabinet to a special session where he approved Union General Benjamin Butler’s decision not to return fugitive slaves to their owners. Butler had claimed that, because Virginia had seceded from the Union, the federal government was no longer under any obligation to return escaped slaves. Behind that decision lay decades of controversy caused by slaves who continually expressed their opposition to bondage by the deceptively simple act of running away. Thanks to Richard Blackett’s impressive research, we now have a much better understanding of how that happened.

This Issue

December 6, 2018

Saboteur in Chief

That Formal Feeling

Opioid Nation

-

1

The Union Army adopted the same tactic in the first year of the Civil War. When slaveholders or their representatives arrived at military camps demanding the return of their slaves, Union officers often demanded substantial documentation as a means of thwarting the rendition. ↩

-

2

Lincoln’s concerns about the political wisdom of calling for repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law were expressed in an 1859 exchange of letters with Salmon P. Chase of Ohio. See The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy P. Pasler (Abraham Lincoln Association, nine volumes, 1953–1955), Vol. 3, pp. 41, 384, 386, 514. ↩