In 2016, the year Macedonia completely closed its borders to Syrian refugees, I met a young Palestinian man named Walid in a squalid army-run camp on the Greek island of Samos. I was writing a magazine story on the conditions in such camps following the deal that March between the EU and Turkey, which was intended to reduce the flow of migrants into Europe. Since media permits were not forthcoming, I ended up sneaking in through a hole in the fence. As I interviewed refugees, Walid approached me.

He had been at the camp for nine months, he said, sleeping in a tent inside a shipping container while the authorities figured out what to do with a Palestinian who had been born in northwest Syria. In that time, he’d seen a lot of reporters, but little change. “Do you think these articles will do anything?” he asked.

I paused to think about it. “No,” I answered. “But it’s important to keep a record.”

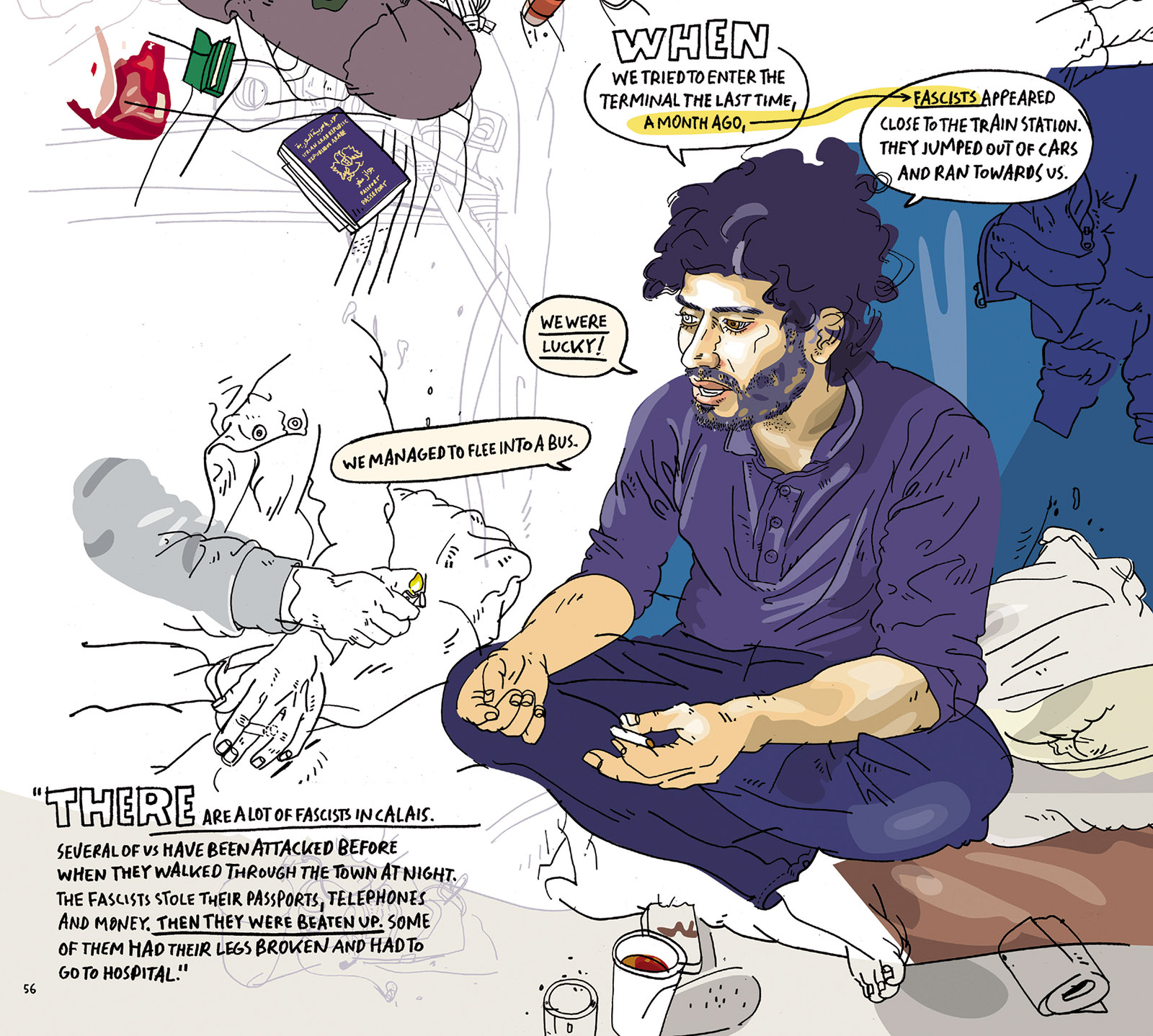

In the years that followed, I thought often about Walid’s question. Like Olivier Kugler, Don Brown, and Kate Evans, who have each published new books of comics journalism on the subject, I spent years covering the mass movement of human beings that is referred to in Europe as the “refugee crisis.” I was a Western journalist traveling freely on my powerful passport, paid to document the misery of people whose passports trapped them in poverty and war. I shared cigarettes with refugees in tents in Iraq, Lebanon, and Greece. I listened to little boys talk about the car bombs that killed their fathers. Mothers told me that drowning in the Mediterranean would be better than one more day rotting in this goddamn camp.

This Issue

December 6, 2018

Saboteur in Chief

That Formal Feeling

Opioid Nation