One of the few issues that many Americans can agree on in 2018 is, improbably, marijuana legalization. Pot is now legal in thirty-three states and Washington, D.C. In April, John Boehner, the former Republican Speaker of the House, made the rounds of the morning TV talk shows to announce that he now supported decriminalization. Boehner, a former Big Tobacco lobbyist, had declared in 2015 that he was “unalterably opposed” to making pot legal. Now, perhaps hoping to cash in on the marijuana “green rush,” he sits on the advisory board of Acreage Holdings, a New York City–based marijuana startup headed by investment bankers. Acreage hopes to be to Big Pot what R.J. Reynolds, Boehner’s other employer, is to Big Tobacco. Acreage’s CEO, Kevin Murphy, optimistically predicts a “massive consolidation in this business” that will earn his company billions by 2020.

Can anyone corner the market on this plant, which has flourished all over the world for thousands of years? Those who have spent their entire lives managing the variables of the marijuana trade are less certain than Murphy or Boehner that monopolizing the market is possible. They know that the only certainty in this industry is uncertainty.

Emily Dufton’s timely book Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America deftly chronicles the battle over the most popular semi-illegal substance in the US. It is a story of revolution, counterrevolution, pyrrhic victories, and, now, crass opportunism. Above all, it is a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of myopic zealotry. Dufton interweaves a history of 1960s counterculture with the emergence of marijuana advocacy groups like the well-known National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) and lesser-known activists.

Those who did not live through the 1960s may find it difficult to appreciate just how subversive this plant was once thought to be. Because the US government viewed pot smoking as a rejection of postwar American values, it considered the battle against marijuana an important front in the culture wars. To the Nixon administration marijuana was not a legal or economic issue—it was a moral one. The president considered homosexuality, marijuana, and immorality “the enemies of strong societies” and compared them to the “plagues and epidemics of former years.”

Grass Roots and most scholarly studies about pot have a large and excusable blind spot. Much of the history of the American marijuana business is unknown simply because of its criminal nature. Perhaps the most important activists among those who found what Dufton describes as a “higher calling” in the battle over cannabis during the 1960s were men and women whose deeds spoke louder than their words: the hippie smugglers and clandestine pot farmers that Timothy Leary called “prophets,” “righteous dealers,” and “spiritual outlaws.” The Brotherhood of Eternal Love, based in Laguna Beach, California, was thought to be responsible for putting more hashish, marijuana, and LSD on the American streets than anyone else during the 1960s. Its members were unique in the drug trade because they had a virtual monopoly on LSD and hashish and did not exploit their market advantage. “We believe that dope is the hope of the human race, it is a way to make people free and happy,” one Brotherhood member explained to the East Village Other in 1969. “Our lives have been saved from the plastic nightmare because of dope and we would feel selfish if we just stayed in our beautiful utopia.”

It took many years for law enforcement officials to realize that the pot trade was nonhierarchical and disorganized. Because most of America’s marijuana in 1969 came across the southern border, the Nixon administration launched a large-scale border crackdown that year called “Operation Intercept.” It succeeded in slowing the flow of commercial marijuana, but it had unintended consequences. It pushed smugglers further down the Hippie Trail, a modern-day cannabis Silk Road that started in Europe and wound through Morocco, Turkey, Lebanon, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Kathmandu, Nepal, Thailand, and Laos.

When Congress passed the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act in 1970, it “temporarily” classified marijuana—along with heroin, LSD, ecstasy, and peyote—as a Schedule 1 drug with “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black,” President Nixon’s assistant for domestic affairs, John Ehrlichman, admitted in an interview, “but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”*

The president also set up a blue-ribbon committee chaired by Pennsylvania’s former Republican governor, Ray Shafer, to conduct the most exhaustive study of marijuana in American history. Nixon was furious when this two-year study concluded that pot was relatively harmless and should be legalized. The government’s emphasis on marijuana was soon to be regarded, even by the DEA, as a distraction from the real crisis: heroin.

Advertisement

During Nixon’s first term, while his administration was obsessing over pot, the number of heroin addicts in America doubled. In 1969 the US military cracked down on the use of marijuana by GIs in Vietnam. By 1970, Vietnam was flooded with 90 percent pure, No. 4, “China White” heroin. In April 1971 a congressional subcommittee concluded that heroin use by GIs in Vietnam had reached “epidemic proportions” and that 10 to 15 percent of American soldiers were using the drug.

After Nixon’s resignation in 1974, the Ford administration softened the federal government’s position on cannabis and concentrated on heroin instead. Above all, Ford rejected the idea that drug use could ever be eliminated completely. By the time Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, marijuana legalization seemed possible and had support in the White House. Carter’s special assistant on drug abuse, Dr. Peter Bourne, wanted to decriminalize pot and shift the government’s attention to heroin. These efforts were encouraged by pot lobbyists in Washington, D.C., led by NORML’s R. Keith Stroup.

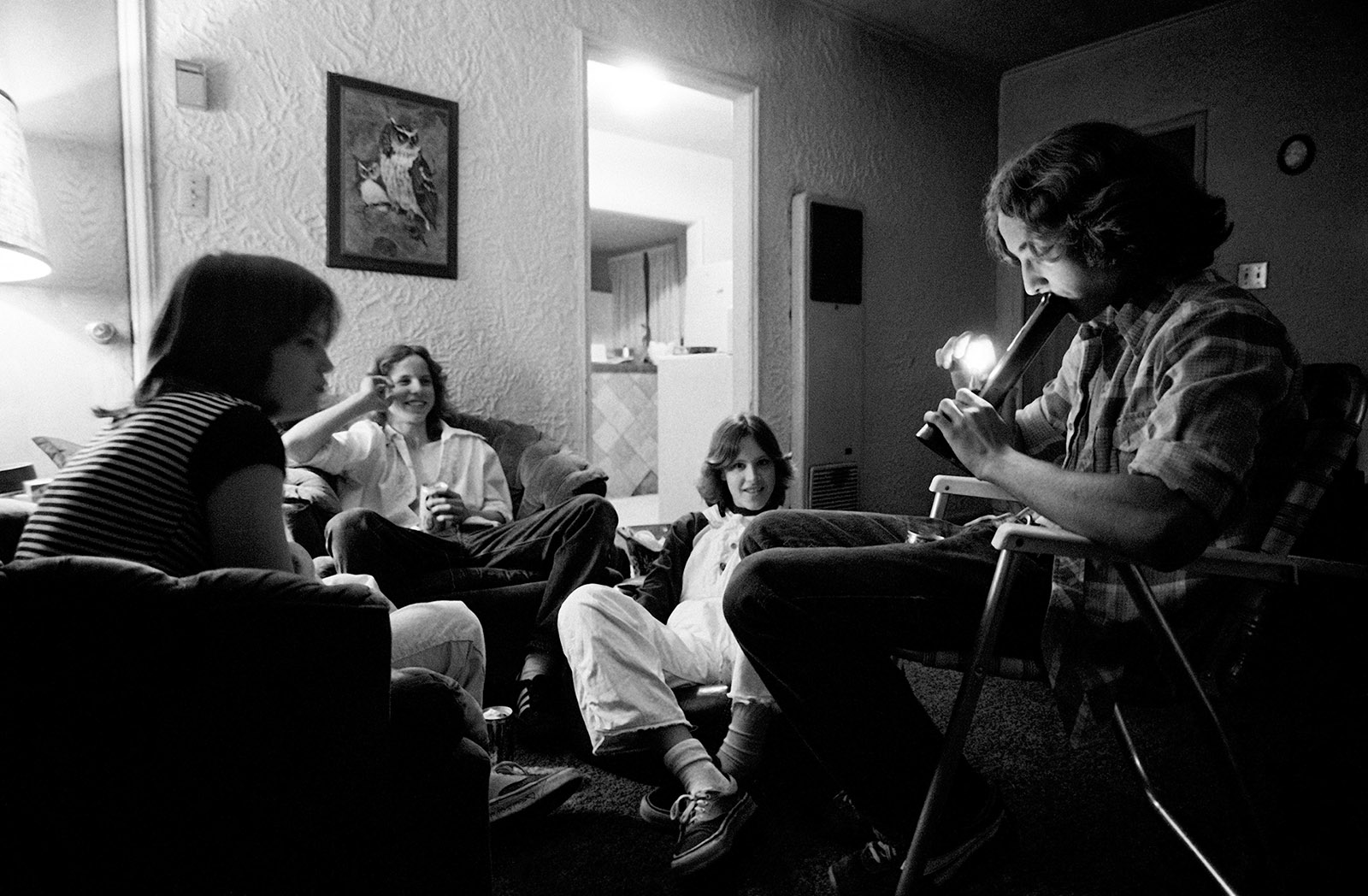

But as decriminalization looked increasingly likely, there was an explosion in unregulated ancillary industries like the sale of pot paraphernalia, some of it marketed to minors. The strongest section of Grass Roots is Dufton’s analysis of the “Nosy Parents Associations,” which emerged in an Atlanta suburb in 1976 after Marsha Manatt Schuchard hosted a birthday party for her thirteen-year-old daughter. Alarmed by the strange behavior of the teenage guests, she searched her yard after the party and found marijuana roaches and empty liquor bottles. The concerned mother formed a parents’ group to combat the marijuana industry, which she believed was targeting underage users.

Rates for adolescent pot smoking remained high during the 1970s, and parents’ groups spread nationally. By 1980, the National Federation of Parents for Drug Free Youth (NFP) had over four hundred affiliated groups in forty-eight states with the new goal of eliminating all drug use in America. Soon politicians who supported legalization realized that it was a political problem. Even President Carter reversed his position on the issue during the 1980 election.

Former California governor Ronald Reagan hated pot with a passion unseen since Nixon and considered the battle against it part of a larger culture war. During the campaign he said that “leading medical researchers” considered marijuana “probably the most dangerous drug in the United States.” After Reagan’s election, he appointed Carlton Turner as his senior adviser on drug policy. Turner had been in charge of the federal government’s marijuana farm at the University of Mississippi, where he had made it virtually impossible to conduct scientific research that the FDA would accept as “credible.” “Stop talking about whether marijuana’s good or bad for you,” Turner explained. “I’m here to tell you it’s bad. The scientists will tell you they can’t say for sure because as soon as they do they get no more research money.” Researchers who managed to navigate the government’s regulations were supplied with low-quality, often moldy marijuana leaves and stems, not the flowers, which are rich in CBD and THC and contain the plant’s medicinal properties. The soon-to-be drug czar compared pot to “hard-rock music, torn jeans and sexual promiscuity.”

Reagan considered pot “a gateway drug” that led users to heroin. First Lady Nancy Reagan turned to the issue of drugs to transform her image from that of a thin-skinned social climber to one of a caring parent. Grass Roots reveals how, instead of throwing her weight behind the hugely successful parents’ movement, she co-opted an Oakland-born antidrug campaign called “Just Say No.” Founded by the community activist Joan Brann, it was originally aimed at inner-city youth. Just Say No became what Dufton describes as “little more than a national merchandising opportunity.” Thanks to the first lady, Procter and Gamble turned “adolescent drug abuse prevention into a marketing slogan used to sell everything from paper towels and cake mix to clothing and potato chips.”

Even with adolescent marijuana use dropping by 1983, the Reagan administration ramped up the war on pot. While the efforts against pot succeeded, there were disastrous unintended consequences in the places where they were most successful, because those who could no longer afford pot replaced it with cheaper, more dangerous drugs like crack and methamphetamines. Hawaiian police launched “Operation Green Harvest” in the late 1970s in an attempt to crack down on the archipelago’s enormous cannabis industry. It quickly morphed into a quasi-military campaign that used photo mapping, herbicide-armed helicopters, and commando cops who descended from fast ropes into sugarcane fields and backyards to confiscate pot plants.

“Green Harvest” quadrupled the price of indigenous Hawaiian strains like Kauai Electric and Puna Butter, but it also destroyed an industry that generated as much revenue for the islands as sugar cane or pineapple. It did not slow the demand, and soon much of Hawaii’s pot was imported from California and Mexico, at a much higher price. In a 1989 report, Hawaiian attorney general Warren Price prophetically predicted that “victories over the pakalolo [marijuana] industry would create a vacuum that harder drugs could fill.” The drug that filled that void was law enforcement’s worst nightmare: an incredibly addictive, smokable form of methamphetamine called “ice.” By the 1990s, Hawaii was suffering from the worst meth epidemic in American history.

Advertisement

The DEA’s efforts against Thai marijuana during the 1980s, although successful, produced similar pyrrhic victories. From the mid-1970s through the 1980s, Thailand was one of the biggest exporters of high-quality marijuana to the United States. While Nepalese Temple Balls, Afghan Primo Hash, and Papa Grande’s Colitas were valuable, if you had real Thai sticks, you named the price—consumers happily paid ten times more than anyone had ever paid for marijuana before.

During the 1980s, the US convinced the Thai government to crack down on marijuana. The campaigns against Hawaiian and Thai pot can be counted as two of the few unequivocal victories in the War on Drugs. But it is difficult to say what they actually won, because drug users did not stop using drugs when marijuana became scarce and even more expensive. Well-off users simply paid much more for marijuana, and those who could no longer afford it turned to meth instead.

Neither the supply nor the demand for marijuana was reduced. With the Thai exporters shut down, American growers easily supplied the nation. As Roger Warner pointed out in his book The Invisible Hand: The Marijuana Business (1986), unlike heroin and cocaine, “nothing seems to control the marijuana trade but the forces of supply and demand. The organizations that deal in marijuana are shifting and decentralized, nearly always working in ignorance of each other.” American law enforcement officers had little time to chase pot smugglers and growers. Florida was flooded with cocaine and the violence that came with it. This epidemic transformed the American legal landscape and, Dufton convincingly argues, ushered in a set of racially discriminatory drug laws.

Prior to the 1980s, powdered cocaine was a rich person’s drug. Once it was discovered that coke could be mixed with baking soda and water and reduced over heat to a smokable solid, the drug spread to the inner cities. Instead of buying a gram of powder for $70, users could now buy a highly addictive, easily smokable “rock” of crack for as little as $5.

The new sentencing guidelines in the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 were blatantly racist. Anyone caught with just five grams of crack faced a mandatory minimum five-year sentence, but it took five hundred grams of powdered cocaine to receive the same sentence. Because whites typically snorted powder and blacks smoked crack, this distinction resulted in the disproportionate imprisonment of black drug users. In three decades, America’s prison population went from 300,000 in 1970 to two million in 2000, by far the largest prison population of any industrial nation. “By 2000,” Dufton points out, “the Unites States had imprisoned a larger percentage of its black population than South Africa at the height of apartheid.”

Carlton Turner’s forced resignation as drug czar in 1986—after he told a reporter that “marijuana leads to homosexuality, the breakdown of the immune system, and ultimately, AIDS”—signaled the start of the next counterrevolution. The legalization movement’s new message that medical cannabis could be used by adults to combat glaucoma and to alleviate the symptoms of AIDS, Dufton points out, “changed the face of marijuana activism.” Selfless caregivers, like the San Francisco waitress Mary Jane Rathburn, baked and distributed marijuana edibles to AIDS patients, while others made sure that AIDS and glaucoma patients had access to cheap marijuana. To deny that marijuana, a well-known appetite stimulant, was one of the most effective medicines to counter the “wasting syndrome” that afflicted AIDS patients now seemed inhumane.

California led the way on legalization in 1996 after the state’s voters passed Proposition 215, which allowed the use of medical marijuana. A hydra-headed, gray-market industry emerged from the chaotic legal situation this legislation created. Because primary care physicians feared repercussions from the American Medical Association, many refused to recommend medical marijuana. Rogue physicians stepped in to fill the gap. For a fee, a doctor working outside his or her traditional medical job would conduct a cursory consultation and prescribe marijuana. So promiscuously were medical marijuana cards issued that the distinction between legitimate “medical” use and recreational use disappeared early on. As David Holland, one of the nation’s leading marijuana lawyers, explains, the government’s refusal to remove cannabis from the Schedule 1 list has produced a legal crisis:

By permitting thirty-three states to develop both medical and responsible adult use regulatory schemes…the federal government has intentionally and aggressively undermined the supremacy of federal law which still keeps marijuana in Schedule 1 despite the majority of the states adopting its medical and recreational use.

The solution, Holland concluded, would be for the Schedule 1 designation to be “changed by Congress or the Courts.”

Dufton could not have predicted what has happened since her book appeared last year. Given how rapidly marijuana legalization has advanced in 2018 alone, the discussion of legalization in Grass Roots already feels dated. For many Americans who have spent their lives under the prohibition of pot, the book’s “Lessons Learned” conclusion is too conciliatory. Today, it is clear that the US government used marijuana laws to target minorities and members of the counterculture. Many are not so quick to forgive and forget while there are still dozens of Americans, like the hippie smuggler John Knock and the paraplegic Michael Pelletier, serving life sentences for pot. “America is full of hypocrites,” Knock, a nonviolent, first-time offender, told a reporter days after President Obama rejected his request to commute the double life sentence plus twenty years, of which he had already served more than twenty years. “We’re sitting in here watching as [state after state] legalizes…and there are people in here doing life for pot, an accepted recreational and medical drug in the majority of the states in America.”

With the war on pot winding down, even in California, the state with the longest and deepest relationship with marijuana, there is no consensus on the future of the industry. World-class marijuana has been grown in Santa Barbara since the 1970s, and hundreds of tons of Thai pot were offloaded at private coastal ranches there and on Central California’s “Lost Coast” during the 1970s and 1980s. When smuggling became too risky, smugglers instead began to grow marijuana in the Mediterranean microclimate. For many, the pot trade quietly bought them the freedom to pursue their dreams. Now the lines are drawn between indigenous black- and gray-market growers and venture capitalists from out of state with no links to the illicit trade. In California, legalization varies not only from county to county but also from city to city.

The bucolic seaside town of Carpinteria, near Santa Barbara, once known for flowers and avocados, is now known for marijuana. More than forty years ago, Dutch immigrants began to grow flowers there and became pioneers in hydroponic greenhouse farming. So much pot is grown in the town’s 280 acres of greenhouses that during certain times of year, you can smell the plant’s skunk-like odor in the heart of downtown. Visitors drawn to this small surf town do not always come in peace. In December 2017 thieves cut across an avocado farm in order to rob the adjacent marijuana-filled greenhouse. For the avocado farmer, this was the third time his property had been so used. “We don’t see eye to eye anymore,” the farmer told a local reporter. “Carpinteria is a small community and it has no place for marijuana growing.”

One Santa Barbara family that has been in the pot trade since the 1960s, the third generation of which now works in the industry, agreed to speak with me on the condition of anonymity. They presell much of their crop to customers willing to pay more for a product they know to be not just the highest quality but also free of pesticides and mold. One of the farmers I spoke with looks at much of the cannabis sold in LA dispensaries in the same way that an oenophile would look at boxed wine.

Until 2017, the family’s meticulously grown outdoor organic pot sold for $1,200 per pound. This year the price was only $1,000, but they were willing to suffer a drop if it hurt out-of-state speculators. “Many of the carpetbagger growers don’t even smoke it,” said the family’s patriarch, who spent close to a decade in prison for pot smuggling. “They think it is all the same, they think it is like alcohol—easy money.” He predicted a “range war” and thought it would take a decade for the industry’s legal status to become clear.

A Lost Coast family that had been in the trade since the 1960s also spoke to me on the condition of anonymity. “Growing cannabis is not easy,” one of these farmers said. He compared it to growing orchids. “Not only does pot have to be fresh, it can’t be dirty, dusty, moldy, or full of pesticides.” Today this family operates on a partially legal basis and threads the loopholes of the numerous and sometimes contradictory laws that govern marijuana cultivation, distribution, transportation, testing, retail sale, and extraction. “California screwed it all up,” he said. “The problem is that you have a lot of people making decisions that have no real experience with cannabis culture.” He called “the Green Rush” the worst exhibition of human greed he had ever seen. Worse than the greed was the appropriation of his culture—developed over decades by farmers who cared about the plant and its many properties—by outsiders who were never in the black market. “All the big money is coming in to take the cream after we did all the heavy lifting.”

Before returning to LA I visited Alfonso “Farmer Fonz” Navarro, another twentysomething “hippie redneck”—known in California as a “hipneck”—I met while surfing a remote, shark-infested stretch of the Lost Coast in 2013. At the time, he and his friends were involved in various aspects of the pot trade, and although they were tech-savvy college graduates most had no social media presence and lived comfortably off the grid in boats, cabins, or vans. Above all, they were not risk-averse. These expert surfers and mariners were capable of sailing the treacherous Central California coast in winter and of growing pot at remote mountain locations, and were not afraid to drive vanloads of plant clones from Northern to Southern California.

Navarro studied agricultural engineering, irrigation design, soil science, and crop management, then worked at high-end organic vegetable farms, where he learned how to grow nutrient-dense vegetables using live soil and regenerative farming techniques. Now he works as a consultant to legal growing operations across California. He welcomes more regulations on pesticide testing because “sustainable practices will weed out bad businesses.” The marijuana market is flooded, he thinks, and he is prepared to absorb losses for the next two years.

While some of the Big Tobacco companies are rumored to be positioning themselves to enter the marijuana trade, the pharmaceutical and liquor industries already have. Constellation Brands—the company that owns Corona beer, Svedka vodka, and others—spent $190 million to acquire 10 percent of Canopy Growth Corporation, one of the world’s biggest pot producers. Bayer AG and its ally in the pot trade, GW Pharmaceuticals, already have a large footprint in the medical market.

This might have been expected: no group is more threatened by the speed with which medical marijuana is replacing opiates as pain medication than Big Pharma. Recent studies show that states that have legalized medical marijuana have had a significant drop in opiate addiction. Meanwhile, for every corporate farm growing genetically modified Frankenweed under lights, there are thousands of private citizens discreetly tending clandestine outdoor gardens. They have spent their lives developing tradecraft and new genetic strains of weed, and they will keep supplying friends and family as they always have, whatever the law says.

By far the most pathetic figure in the saga of the Green Rush is former attorney general Jeff Sessions, who suffered a humiliating defeat when President Trump struck a deal with Colorado senator Cory Gardner that allowed Colorado to protect its stance on legalization. Sessions’s strident opposition to pot—like that of the well-known anti-pot crusaders Sheldon Adelson, Carlton Turner, Mel Sembler, and David Frum and his allies at the well-funded, media-savvy lobbying group Smart Approaches to Marijuana (SAM)—is the last gasp of a dying tradition. SAM has repackaged many of the old prohibitionist arguments, and Frum, George W. Bush’s former speechwriter, has used his position in the mainstream press to disseminate SAM’s talking points with the same conviction with which he once declared the war on terror “An End to Evil.”

The British Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report (1894), the La Guardia Committee Report (1944), the Baroness Wootton Report (1968), the Canadian government’s Le Dain Commission (1970), and the Shafer Commission Report (1972) reflect one hundred years’ worth of research concluding that marijuana is relatively harmless. Edible and concentrated cannabis products need better regulation, but that problem—compared to those posed by heroin, cocaine, methamphetamines, and FDA–approved opiates, which killed more Americans in 2016 than died in the Vietnam War—is not insurmountable.

Dufton argues that legalization remains a social justice issue because black marijuana users are more likely to get arrested for small-time possession than whites. Recently, the hedge fund owner Daniel Loeb led an effort that successfully freed Bernard Noble from a Louisiana prison where he had served seven years for three grams of pot, roughly five to ten joints. But injustices in the war on pot cut across all racial, social, and economic lines, and legalization enjoys a similarly wide range of support. For longtime pot smokers it is about personal freedom; for advocates of social justice it is about mass incarceration; for lobbyists like John Boehner, it is about money.

The American government has not only lost the war on pot; it has also lost the War on Drugs. Today, America is the most drug-addicted nation on earth. It also has the world’s largest prison population and a racist two-tiered judicial system. One would think that the architects of this war would be in political purgatory. Instead they are now trying not only to dictate the terms on which legalization will proceed, but also to cash in on it. Since when do the defeated dictate the terms of their surrender?

This Issue

December 20, 2018

Damn It All

Prodigal Fathers

In the Valley of Fear

-

*

Dan Baum, “Legalize It All,” Harper’s, April 2016. ↩